Media | Articles

6 historic BMW-powered race cars back in action at Laguna Seca

BMW stands on the threshold of a return to Le Mans. The marque’s 23-year absence from endurance racing’s top step—the built-from-scratch prototype class—will end in January of 2023 when the BMW M Hybrid V8 takes to Daytona for IMSA’s season-opening 24 hour race. After a year competing stateside, BMW M will return to the European circuit and to the Circuit de la Sarthe in 2024, powered not by a naturally aspirated, 600-hp V-12, as the LMR once was, but by a turbocharged, electrically assisted V-8.

This year, as BMW’s Motorsport division celebrates its 50th anniversary, the marque brought an unusually rich selection of race cars to compete at Laguna Seca in the 2022 Rolex Monterey Motorsports Reunion (supplemented, of course, by top-shelf racers campaigned by its customers). We were there in person to capture the action and couldn’t resist digging into the history of the chassis on-hand.

If you like your BMW cylinder counts in multiples of six, it doesn’t get much better than this.

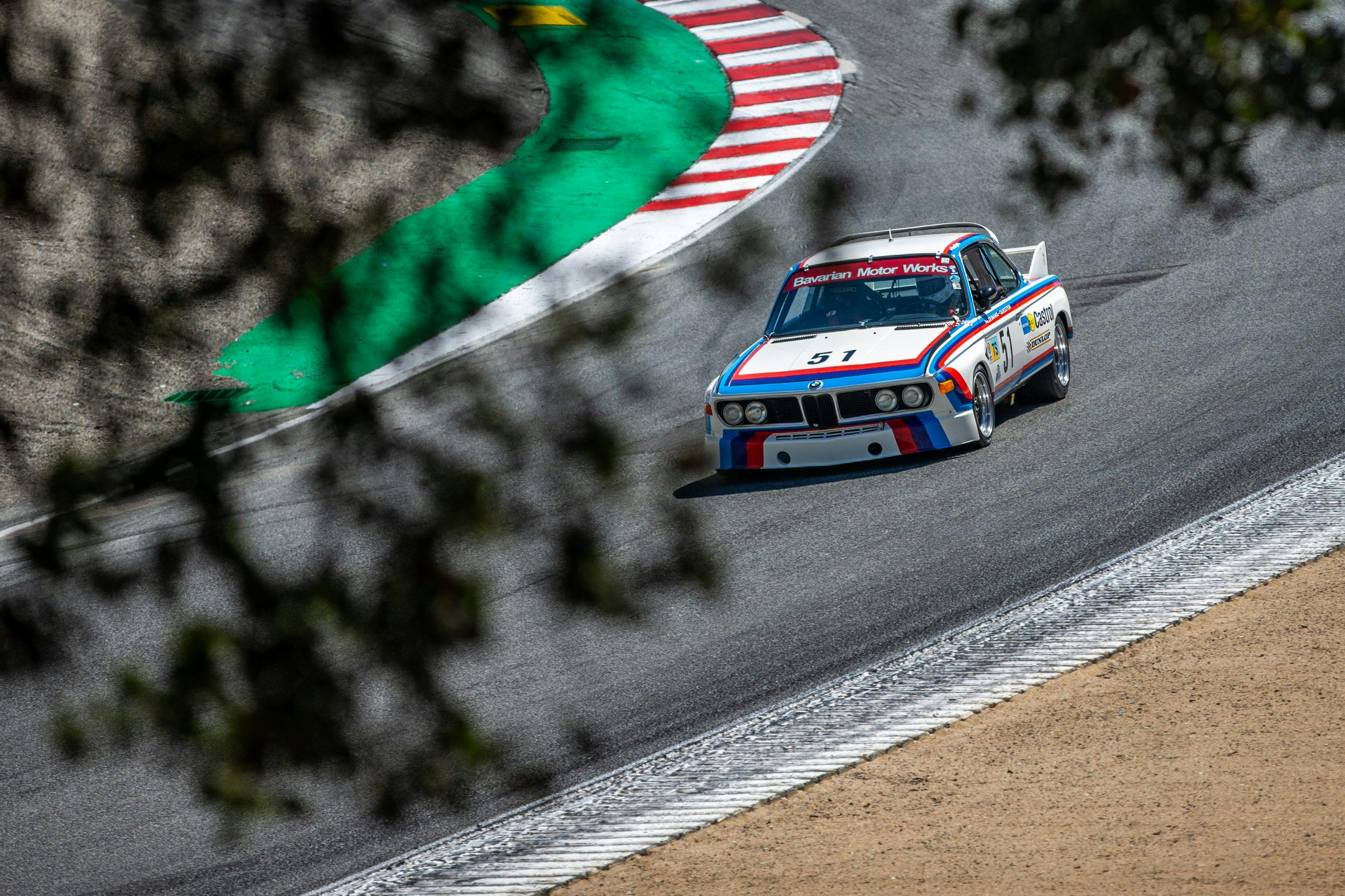

1972 BMW 3.0 CSL

When Bob Lutz, then head of sales for BMW, blessed the organization of BMW Motorsport in 1972, Ford Capris ruled the European endurance circuit. That all changed, of course, when BMW’s 3.0 CSL captured the European Touring Car Championship in 1973—the same year in which this factory-campaigned CSL, now owned by Scott Hughes, won its class at Le Mans.

Like many of the other BMWs on this list, #51 crossed the pond and raced stateside: in 1975, it was one of two cars imported by professional rally driver John Buffum of Vermont to compete in IMSA, a series on which BMW focused after the OPEC oil crisis made European competition politically unwise. After one season, the pair passed to Mexican owners who wanted to run them at Daytona; but after a test at Road Atlanta totaled one of the cars, #51 bounced through several owners. It was restored to its original works livery by Richard Conway of North Carolina, eventually landing in the hands of Hughes. He and his wife Fran, who owns a BMW collection of her own (which includes an Isetta 600 limo named Ms. Daisy and a Z1), were early devotees of the Munich brand. When they joined the BMW Car Club of America, the club’s membership was only in the four digits. The couple also founded the very first BMW club driving school in the U.S., in 1974 at Lime Rock Park.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The highlight of Scott’s ownership of this CSL came when he ran the car at track where it entered the history books, during the Le Mans Classic. “It wasn’t even on the bucket list,” he says. “It was way above the bucket list.” His excitement is still infectious: “In the middle of the night, in the rain, in the dark … you’re going as fast as you dare, and you’re sort of looking around yourself and thinking, how the hell did I end up here? They’re going to find out I’m here and they’re going to send me home!”

Needless to say, no one did—and the Le Mans class-winning CSL is still within his care.

1981 IMSA M1 Group 4

The one-make Procar championship was the M1’s claim to fame, but not all M1s spent their competitive lives in this sprint-style F1 support series. A few were turbocharged under the FIA’s Group 5 regulations, to mixed success; others, which remained naturally aspirated per Group 4 regulations, fared better. BMW had engineered the M88 straight-six engine for Group 4 competition years before, and these cars hit the grid equipped with forged pistons, reprofiled camshafts, larger valves, massaged exhaust manifolds, and slide rather than butterfly throttles. Power nearly doubled, rising from 277 to almost 500 hp. (The turbocharged Group 5 cars made even more, but were less successful.)

A few Group 4–spec M1s, including this 1980 car, came stateside to compete in the IMSA endurance-racing circuit. In 1981, M1s would capture first and second in the GTO championship. BMW made some slight changes to the cars competing in the longer-distance format, including fitting wider rear fenders and tires and installing rapid-fill fuel systems. If you don’t have a regular-width M1 handy, spotting an IMSA-spec car is easy: The rear quarter “windows” are blocked out by gas filler caps. This particular chassis was a spare car in BMW’s 1981 IMSA arsenal. As such, it remains remarkably clean and makes frequent appearances at historic events on behalf of BMW Motorsport.

1996 McLaren F1 GTR

It didn’t race under the BMW banner, but McLaren’s F1 wouldn’t have become a legend—on the street or the track—apart from BMW’s V-12. There is no mic drop like winning the crown jewel of endurance racing on your first attempt. With the BMW-powered F1 GTR, McLaren F1 GTR accomplished exactly that, in 1995. Privateer-campaigned F1s captured first, third, fourth, fifth, and thirteenth place in one of the wettest 24 Hours of Le Mans ever recorded. (17 hours of steady rain!)

After such a testament to the capability of its V-12, BMW wasted no time purchasing its own pair of F1 GTRs for 1996’s 24-hour event at Le Mans. One car, chassis 16R, was sponsored jointly by BMW UK and BMW France, with its tail livery split between the Union Jack and the Tricolore; the second by Munich’s North American subsidiary, its rear draped with a Stars and Stripes design. Both were campaigned by Team Bigazzi. This, as you’ve already spotted, is that second car, chassis 17R. It only competed three times in-period, all with the BMW-backed, Italy-based Team Bigazzi SRL: at Silverstone, to qualify for participation at Le Mans; in qualifying at the Circuit de la Sarthe; and in the race itself, where it finished 8th overall after a punctured radiator put it down-field. (The sister car finished 11th).

Part of the sponsorship deal was that, after each car retired from active duty, the subsidiary would own it. After making a deal with its French counterpart for chassis 16R, BMW UK ended up selling the racer. To this day, BMW of North America has never parted with its GTR. “Various people within BMW have grown to love it and squirreled it away for all these years,” says Tom Plucinsky, head of BMW product communications. 2022 marked the first year that BMW has competed with the car; though BMW keeps it in running condition, testing it yearly, and tapped Bill Auberlen to do a few parade laps at Laguna Seca in 2016 for the marque’s 100th anniversary, it hasn’t been driven in anger since 1996 until this past weekend.

1999 BMW V12 LMR

In lieu of a featured marque, the 2022 Monterey Motorsports Reunion is honoring an event: The 24 Hours of Le Mans, which celebrates its 100th anniversary this year. For the first time since this racer won the event in 1999, powered by a BMW-built V-12 nearly identical to the McLaren F1 GTR’s, BMW will be returning to the top class of endurance racing. This group is populated by “prototypes,” cars built from scratch rather than, as in various GT classes, on a production chassis. For the inaugural year of the LMDh regulations—which allow prototypes to compete with minimal modifications in both Europe’s World Endurance Championship and the stateside IMSA series—BMW is campaigning a Dallara-built car, the “M Hybrid V8.” (A rather predictable moniker, but regulations specify that the car’s name must contain the word “Hybrid.”) The racer will take to the Circuit de la Sarthe 23 years after the automaker’ last top-tier effort—The Le Mans Roadster, or LMR—descended on the endurance-racing world.

In 1999, the LMR became the first car since Porsche’s 962C in 1987 to win both the 12 Hours of Sebring and the 24 Hours of Le Mans in the same year. Not with the same chassis, however; honors for the Sebring victory go to this car, which won by what was then the narrowest margin in the race’s history: 9.2 seconds. Another of the five LMRs built took top honors at the Circuit de la Sarthe. The model was extremely successful: Every car finished except for one, which DNF’d in spectacular fashion at Road Atlanta in 2000 when Bill Auberlen’s car caught air in a precise and disastrous fashion, flipping nose over tail to land on the wheels, his foot still mashed on the gas.

BMW/Schnitzer 1974 CSL

No, our photographer didn’t catch a strange ray of Californian sun on this CSL: That third stripe on this CSL really is orange.

Though CSLs are commonly done up in Works colors today, only BMW-campaigned cars were permitted to wear the blue, purple, and red stripes in the ’70s. The one in-period exception was this car, campaigned by BMW dealer Schnitzer and brought to 2022’s Rolex Reunion by Vintage Racing Motors of Redmond, Washington. Originally delivered to Schnitzer as a 2800 CS, the car underwent not one but two transformations: From 2800 CS to CSi, thanks to Schnitzer’s installation of a Kugel-Fisher mechanical fuel-injection system; and then from CSi to CSL in 1974. The story goes that erstwhile Motorsport sponsor Texaco, represented by the red, objected to a non-factory car wearing its particular shade. Schnitzer obviously wanted to leverage his unique permission from BMW to run their livery, so he compromised with this Day-Glo orange.

The Schnizter CSL differs from the works cars underneath its skin, too. The pickup points of the front suspension are slightly different, for one, and the exhausts exit slightly earlier on the sides of the car (any passenger will be cramped by a corresponding bump-out in the footwell). Underneath and behind the drivers’ seat are four bolts that anchor an extra oil cooler for the differential. It’s period-correct in everything except the wheels—because of safety concerns. Schnizter originally ran magnesium rims, which, decades on, don’t take kindly to Magnafluxing. The Seattle-area shop uses Alpina wheels instead. Until it was purchased and subsequently restored the car ten years ago, it had never left Europe.

1975 BMW CSL

You can’t have too many Batmobiles, can you? A broken flange between the driveshaft and diff forced this BMW-owned CSL onto the sidelines at Laguna this weekend, but the last CSL built for IMSA competition is worthy of attention all the same—especially because it will soon swap #25 for #24.

That’s the number it wore for its highest in-period finish, a second place at a six-hour race at Riverside. Chassis #985 suffered a case of mistaken identity for a few years, in fact, until modern BMW realized that ’70s BMW had chosen a backwards serial-number system: Those of the street cars, the homologation chassis, started at 000 and counted up, but those for the race cars started at 999 and went down. So this, the oldest car, has the highest serial number—not the lowest, as you—and any German worth their schnitzel—would expect.

Bonus: 2020 M8 GTLM #24

The most recent BMW race car didn’t take to the track this weekend—but it may not remain on the sidelines for long. The GTLM class winner of the Rolex 24 at Daytona is for sale, complete with an extra set of wheels and “the typical consumables,” so a cash-flush customer could easily return it to action. One of eight chassis used by BMW Team RLL across three seasons of IMSA competition (2018, ’19, and ’20), chassis 1809 was put through its paces as recently as February, at Palm Beach International Raceway at the hands of IMSA’s winningest driver, Bill Auberlen. Interested? Drop an email to BMW of North America.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

The BMW M8 shot was taken at Daytona, not Laguna Seca. Nice try though, but learn about motorsport for next time.