Media | Articles

Vincent’s snarling Rapide can still mix it on modern roads

Some vehicles have a reputation that demands to be experienced firsthand, and the Vincent Rapide is definitely one of them. The bike’s name explains, though possibly doesn’t excuse, the fact that shortly after setting off on this 1950-vintage V-twin I was crouching over its petrol tank on a quiet dual-carriageway at a speed best not recorded here.

It was a magical feeling. The big, 988cc V-twin engine between my shins revved softly away and the needle of the big circular speedometer clicked around the dial. As I leant forward into the wind gripping the narrow, near-flat handlebar, the bike stayed stable, feeling as though it could maintain this pace until its petrol tank ran dry.

Speed was always the key attraction of the V-twins from Vincent, the Stevenage firm that produced some of motorcycling’s fastest and most glamorous bikes in the decade after World War II. They were also some of the most expensive. Still are, in fact—a few years ago, one sold at auction for almost $1M in U.S. dollars, a world record for a motorcycle.

Hence the title Speed is Expensive, given to a new movie that tells the glorious but all-too-short story of the firm and its founder Philip Vincent. As narrator Ewan McGregor puts it, the firm’s string of speed records “proved that the Vincent motorcycle was the work of a genius.”

Vincent’s reputation meant that I’d long wanted to ride one, but in doing so I risked disappointment. The Rapide might have ruled the road back in 1950, but it was long ago eclipsed by much more mundane machinery. Maybe this once mighty so-called “snarling beast” will seem old, heavy, and dull in the 21st century?

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

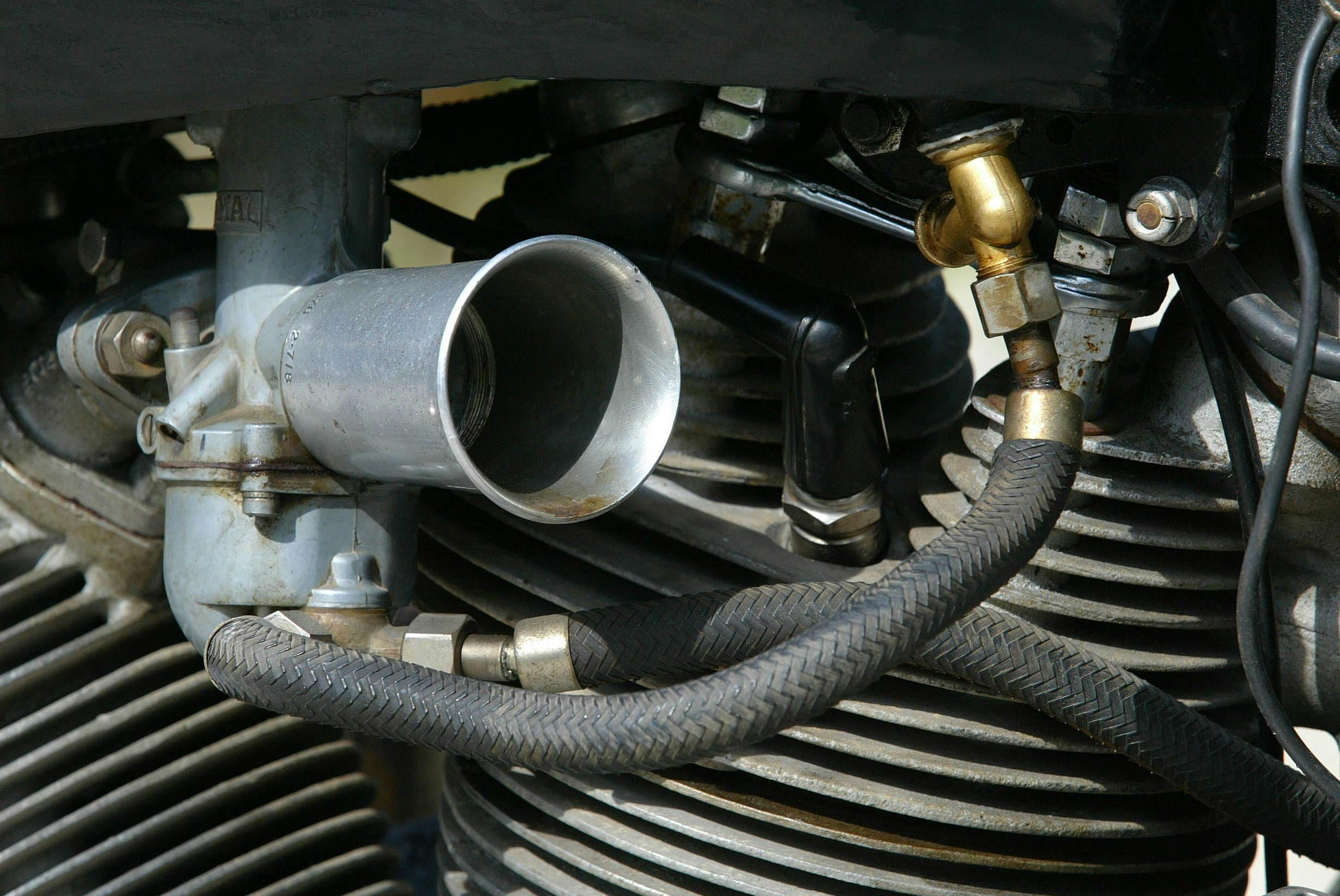

Not a chance. I was captivated from my first sight of a machine whose elegance gave no hint that this bike’s forebear, the original 1936-model Rapide, also earned the nickname “plumber’s nightmare” due to its abundance of external oil lines.

That first Rapide engine, designed by Vincent’s Australian chief engineer Phil Irving, had cylinders set 47 degrees apart. Legend has it that Irving’s inspiration for the V-twin came when two drawings of his single-cylinder Comet engine were blown into a vee shape by a breeze.

The subsequent Series B and C versions of the Rapide were powered by a modified, 50-degree engine with an integrated gearbox and a much neater appearance. The motor dominated the bike visually and was a stressed member of the chassis.

This Series C model’s engine cases were dulled in places but still looked good, enhanced by the marque logos on rocker covers and oil filler cap. There was also a small dent in the petrol tank, which was painted in Vincent’s traditional black with gold pin-striping. The finish was generally less than perfect but that’s because this bike had been ridden and enjoyed over the years rather than simply polished and admired.

It was standard except for a few details, including the big, black-faced 150-mph Smith’s speedometer, which was originally fitted only to the tuned Black Shadow. Other neat details were common to both models, including the sidestand on each side of the bike, the tommy-bar axles that allows both wheels to be removed quickly without tools, and the adjustable foot controls.

The Rapide doesn’t quite have the kudos of the Black Shadow, whose higher compression, polished engine internals, and bigger carbs increased power output from 45 to 55 hp, and top speed from 110 mph to 125 mph. Or precisely 150.313 mph when tuned to Black Lightning specification and ridden by Roland “Rollie” Free, stretched horizontally wearing only a swimming hat, trunks and canvas shoes, to set a world record at Bonneville in 1948—memorably captured in arguably motorcycling’s most famous image.

These days, age has blurred the difference between Vincent models. And any worries that this Rapide’s performance would disappoint disappeared within moments of my setting off. Its flat bars and tall seat gave an unusually high, leant-forward riding position for an old bike, and the attitude helped make the Vincent feel docile as I pottered along minor roads, enjoying the smooth feel of the engine—and its instant response to the throttle.

Given the briefest burst of acceleration, the Rapide proved why the tester from Motor Cycle wrote that: “There has never been a production model with so much to commend it as a road-burner’s dream. From 40 mph up to the maximum of over 100 mph there is thrilling performance available at the twist of the grip. Though the big engine and high gearing suggest easy, loping, fussless mile-eating, there is searing acceleration available if required.”

Decades later this Vincent still had what it required to be fun. Unlike almost any contemporary, it had the pace to keep ahead of modern traffic without feeling strained. And it also had the chassis performance to be enjoyable and safe even on busy roads, though it took some getting used to.

When I tipped the bike into the first tight turn, I was surprised to feel its rear end moving in disconcerting fashion, almost as though the rear wheel was loose. Nothing seemed amiss when I stopped to check. Then I realized that the feeling came from the Vincent’s seat, the rear of which was linked by a rod to the swing-arm, an arrangement which cause it to move slightly as the rear suspension was compressed.

That strange sensation aside, the Rapide handled well, steering quite heavily at low speed but feeling respectably light and maneuverable. This was partly because its wheelbase was short due to Vincent’s minimalist frame design, which used the engine as a key chassis member, in conjunction with a tubular steel frame spine (which carried engine oil) beneath the fuel tank.

This Series C Rapide benefited from Vincent’s own Girdraulic forks in place of the previous model’s conventional girders. It also gained a hydraulic damping unit between its diagonally mounted, side-by-side rear shock units, to assist the original friction dampers. Along with the relatively thick seat, its suspension made the Rapide comfortable even on the long, fast trips that were its speciality.

Braking was respectably good, too, thanks to Vincent’s equally advanced feature of twin drum brakes on both front and rear wheels. And its blend of Dunlop front and Avon rear tires gave no problems, even when I was making use of the generous ground clearance provided by the neatly tucked-in exhaust system.

In fact, the day’s only real problem was that eventually the Vincent began to misfire, and then refused to start after I’d stopped for lunch. The cause was a lack of sparks, due to a battery charging problem that meant it ended its day’s outing in the back of a rescue van.

Reliability was not generally an issue for Vincent, whose main problem was his bikes’ unavoidably high price. In 1950, the Rapide cost £361 (roughly $16,500 in today’s U.S. dollars)—which meant it was more than £60 cheaper than its Black Shadow sibling, but almost twice the £194 (~$8800) price of Triumph’s 650cc Thunderbird, which was launched the same year.

Perhaps it’s no surprise that by this time Vincent was already in deep financial trouble. The Rapide was a magnificent motorcycle but in the post-war years it was too expensive to sell in the numbers required. Adding a fiberglass fairing, to create the Black Knight, increased practicality but also weight and cost—and not sales.

That Speed is Expensive movie title also refers to the fact that Philip Vincent’s commitment to building fast but unprofitable V-twins led to financial ruin. Production ended in 1955. More than half a century later, the Rapide remains a glorious tribute to one man’s vision and refusal to compromise.

***

1950 Vincent Rapide Series C

Highs: V-twin performance with style

Lows: Maybe an occasional niggle

Summary: The ’50s never had it better.

—

Condition and price range: Project, $29,000; daily driver, $36,000; showing off, $42,500

Engine: Air-cooled pushrod V-twin

Capacity: 988 cc

Maximum power: 45 hp @ 5300 rpm

Weight: 456 pounds without fluids

Top speed: 110 mph