Media | Articles

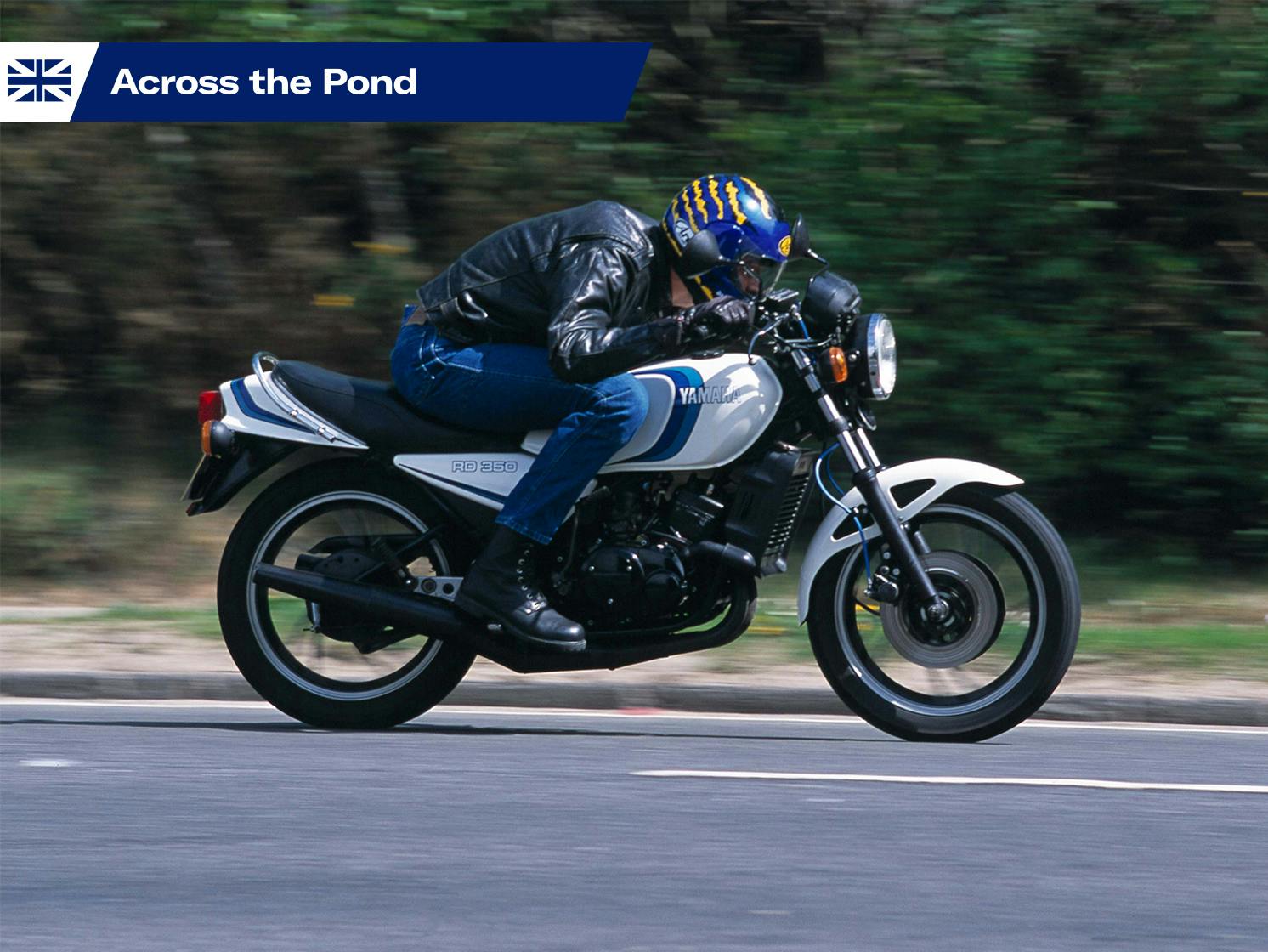

Twist the throttle, and Yamaha’s RD350LC becomes a party animal

It produced less than 50 hp and had a top speed of not much more than 100 mph, but for many riders Yamaha’s raw, racy RD350LC was the high-performance bike of the ’80s.

In many ways, the LC had it all: acceleration, excitement, and handling—plus reasonable practicality, reliability, and economy. Although it had an appetite for fuel and two-stroke oil, the LC was relatively cheap to buy and to run. And it looked great, too, with a restrained style that contrasted with its exuberant personality.

Introduced in 1980, the RD350LC, its LC standing for “liquid-cooled,” was a descendant of the string of outstanding air-cooled two-stroke twins that had earned Yamaha an unmatched reputation for middleweight performance. The line had begun with the 347cc YR1 in 1967, and continued through the ’70s with models including the RD350 and RD400.

The familiar RD initials stood for “race developed,” and were well deserved. Yamaha riders including Britain’s Phil Read had won 250- and 350cc world championships in the ’60s and ’70s, firstly on air-cooled twins and then on the liquid-cooled TZ250 and 350.

The RD350LC was developed alongside an RD250LC sibling that was visually near-identical apart from its front brake having one disc rather than two. The larger, 347cc engine produced 47 hp, a few up on the air-cooled RD400. The LC’s liquid cooling allowed steadier engine temperatures and closer tolerances, and it also reduced noise.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Chassis layout was also influenced by Yamaha’s racers: Instead of a twin-shock layout like the RD400, the LC had a TZ-style monoshock system with the unit angled diagonally under the seat. The 18-inch cast wheels had stylishly curved spokes but in other respects the chassis was conventional, with a twin-downtube steel frame, non-adjustable front forks, and slightly raised handlebars.

Initial reaction was not all positive; some testers wondered whether the LC was too aggressive to appeal to more than a limited section of the market. It didn’t appeal to everyone—but for riders looking for high performance on a low budget, no other bike came close. With a 110-mph top speed, wheelie-popping acceleration, and racetrack credibility, the “Elsie,” as it was soon nicknamed, was the bike of a speed-crazed teenager’s dreams.

Decades later, it still has a rarely matched ability to put a smile on its rider’s face. The entertainment begins the moment you kick the engine into life; there’s no electric starter. The two-stroke powerplant fires with a burbling, rather harsh sound through the twin pipes, which belch a fair bit of smoke and fumes.

Along with good, clear instruments, the Yamaha has excellent controls and a light clutch. Its low-rev performance is pretty feeble; there’s not much power available below about 6000 rpm. That contributed to the Yamaha being docile and easy to ride in town, where its relatively upright riding position also helped make it comfortable. [This is starting to sound like the bike equivalent of the Honda Integra Type-R. —Ed.]

On reaching the open road, though, the RD350LC comes alive. One moment the bike was dawdling along behind a line of cars at about 50 mph; the next, a gap appeared in the oncoming traffic, I stamped down two gears, wound back the throttle, and held on tight as the Yamaha streaked towards the horizon with enough force and noise to send a tingle down my spine.

Somehow the wind-blown riding position and the high-pitched shriek of the exhaust combined to make the bike feel as though it was traveling faster than it really was. In reality, the realistic maximum cruising speed was about 85 mph, so the LC wasn’t fast even by early-’80s superbike standards. At least this now means it can now be caned enjoyably hard on main roads without too much danger to your license.

The Yamaha also provides plenty of entertainment in corners, where its light weight (308 pounds) contributes to very flickable handling. The frame was sufficiently stiff, and its basic geometry and chassis layout good enough, to allow hard riding. This bike’s suspension feels a bit soft and bouncy at times, more than I recall when the LC was new, but still encouraged me to aim into turns with plenty of enthusiasm.

This bike was fitted with non-standard braided front brake lines, which helped the twin discs’ old-fashioned single-piston calipers deliver a respectable amount of stopping power. The narrow Pirelli tires can’t match the performance of wider modern radials, but they gave enough grip to exploit the slim Yamaha’s abundant ground clearance.

Following the LC’s launc,h its impact was boosted by a spectacular one-make racing series. The RD350 Pro-Am championship was contested by a mixture of professional and amateur riders (hence the name) including future 500cc grand prix star Niall Mackenzie. They rode identical bikes that were prepared by Yamaha and allocated by drawing keys from a hat. The result was close, aggressive racing that made great TV and helped earn the LC a cult following with speed-crazed youths.

As well as being quick the Yamaha was also improbably versatile, as one of my favorite trips confirmed. In 1982, I rode to the south of France and back on one, loaded with pillion passenger, throw-over panniers, and tent. The little two-stroke was hardly a tourer but it cruised at an indicated 80 mph-plus on the highway, was quick and agile over winding Alpine passes, and didn’t miss a beat in over 1500 miles. I don’t even recall it being uncomfortable, perhaps partly because we had to stop for fuel every 90-odd miles.

The original LC’s reign was quite short; for 1984 it was replaced by a revamped model, characterized by a new exhaust power valve, which opened and closed to optimize performance throughout the rev range. Other new features, including a bikini fairing and some chassis upgrades, helped make the “Power Valve” LC another hit. Later variants included the fully faired RD350LC F2, which was built in South America rather than in Japan, allowing a more competitive price.

By the time Yamaha retired the LC in the mid-’90s it had been produced in its various forms for well over a decade, and sold in huge numbers all over the world. Almost 30 years after that, its reputation is intact and the original model, in particular, remains one of the best-loved bikes of all time.

1981 Yamaha RD350LC

You’ll love: Rev-happy two-stroke thrills

You’ll curse: Often abused, so buy carefully

Buy it because: Sublime small-bore superbike

Condition and price range: Project, $3500; nice ride, $5500; showing off, $8000

Engine: Liquid-cooled two-stroke parallel twin

Capacity: 347cc

Maximum power: 47 hp @ 7000 rpm

Weight: 308 lbs without fluids

Top speed: 110 mph