Media | Articles

Ton up or not, the Suzuki GT250 X7 was every learner’s dream ride

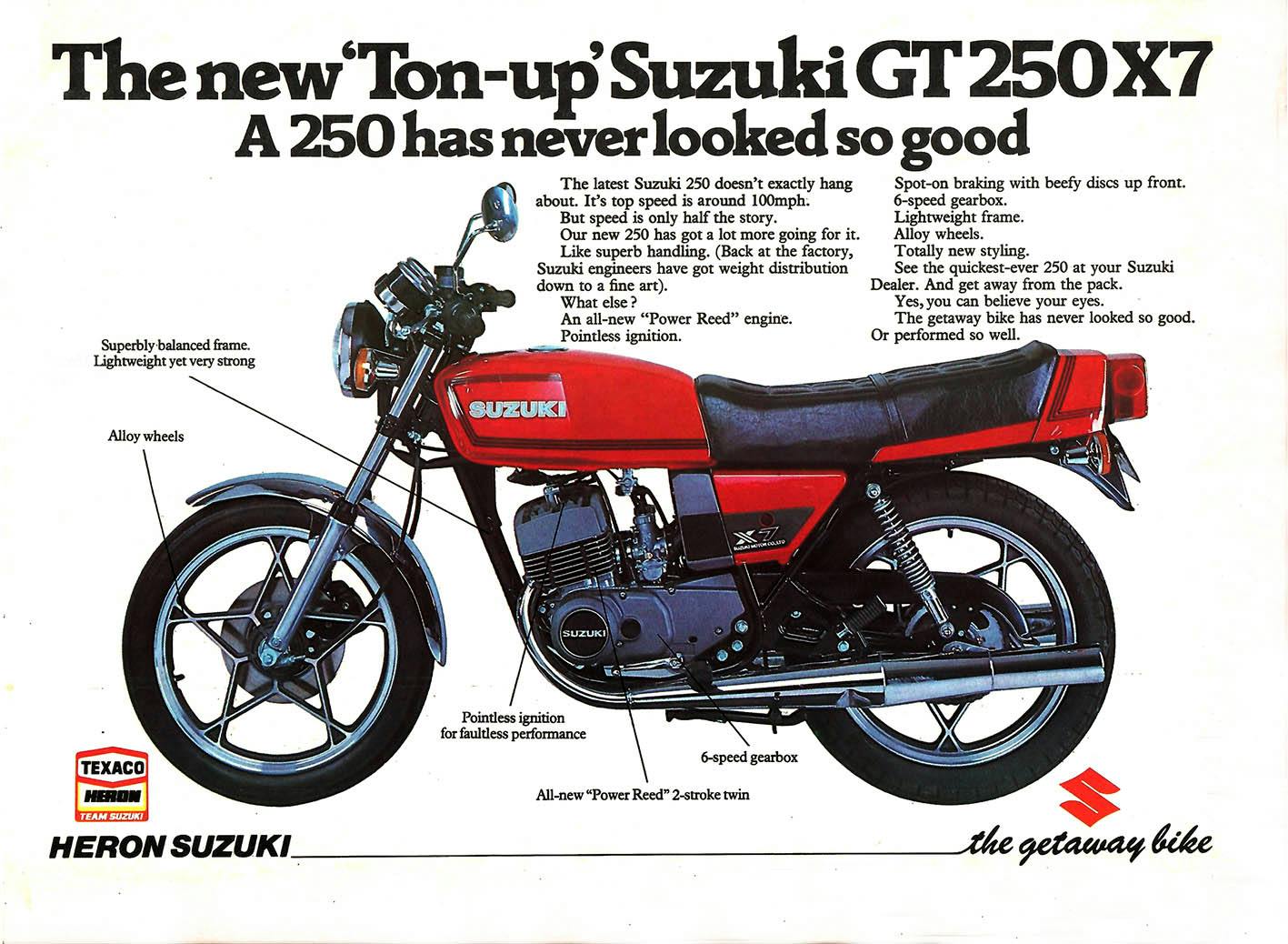

Modern motorbikes are far faster and more powerful than their equivalents from the ’70s—but not if you’re 17 years old and just getting into biking. Back in 1978, speed-crazed teenagers were excitedly taking to the road on Suzuki’s latest learner-bike—advertised as “the new ‘Ton-up’ GT250 X7.”

Suzuki’s headline was just about accurate, too. Motor Cycle News speed-trapped the X7 at 99.34 mph, and a tester from Motorcycle Mechanics magazine recorded a timed top speed of 100.5 mph at Chobham test track in Surrey, albeit after removing its mirrors to squeeze out the last em-pee-aitch.

And that was with an otherwise standard X7, too. With its carburetors tweaked and its standard pipes swapped for screaming expansion chambers, the little two-stroke twin was good for over 115 mph. Learner riders had never had it so good.

Suzuki’s advertising doubtless boosted sales but possibly came at a cost. In 1981 learner riders in the U.K. were hit by a new law limiting them to 125cc and just 11.8 hp, under half the X7’s output. We’ll never know how much the Suzuki’s much-publicized performance had to do with this, but those 100-mph headlines probably didn’t help.

That this happened merely confirms the X7’s status as the quickest, raciest learner bike of the ’70s. It was the latest in a distinguished line of fast, light Suzuki two-stroke parallel twins that went back more than a decade, and included the T20 Super Six, named after its six-speed gearbox.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Other family favorites included the T250 Hustler and the 1973-model GT250, which introduced a “Ram Air” cooling system—basically a bit of flat metal angled to deflect air onto the cylinder head. The GT was a quick and capable bike, but it couldn’t match the pace or popularity of arch rival Yamaha’s RD250.

The comprehensively redesigned GT250 X7, launched in 1978, was intended to change all that. Ironically, given those speed claims and headlines, it was not created with increased top speed in mind. In fact, since the new engine had to meet tighter emissions regs, it produced 2 hp less at the top end, with a maximum of 28.6 hp at 8000 rpm.

What the new engine really gained, besides its first reed-valve induction system, was improved midrange output, which boosted acceleration. Equally significant, the X7 was very light, at a claimed 128 kg (282 pounds) dry—18 kg (40 pounds) less than its GT250 predecessor.

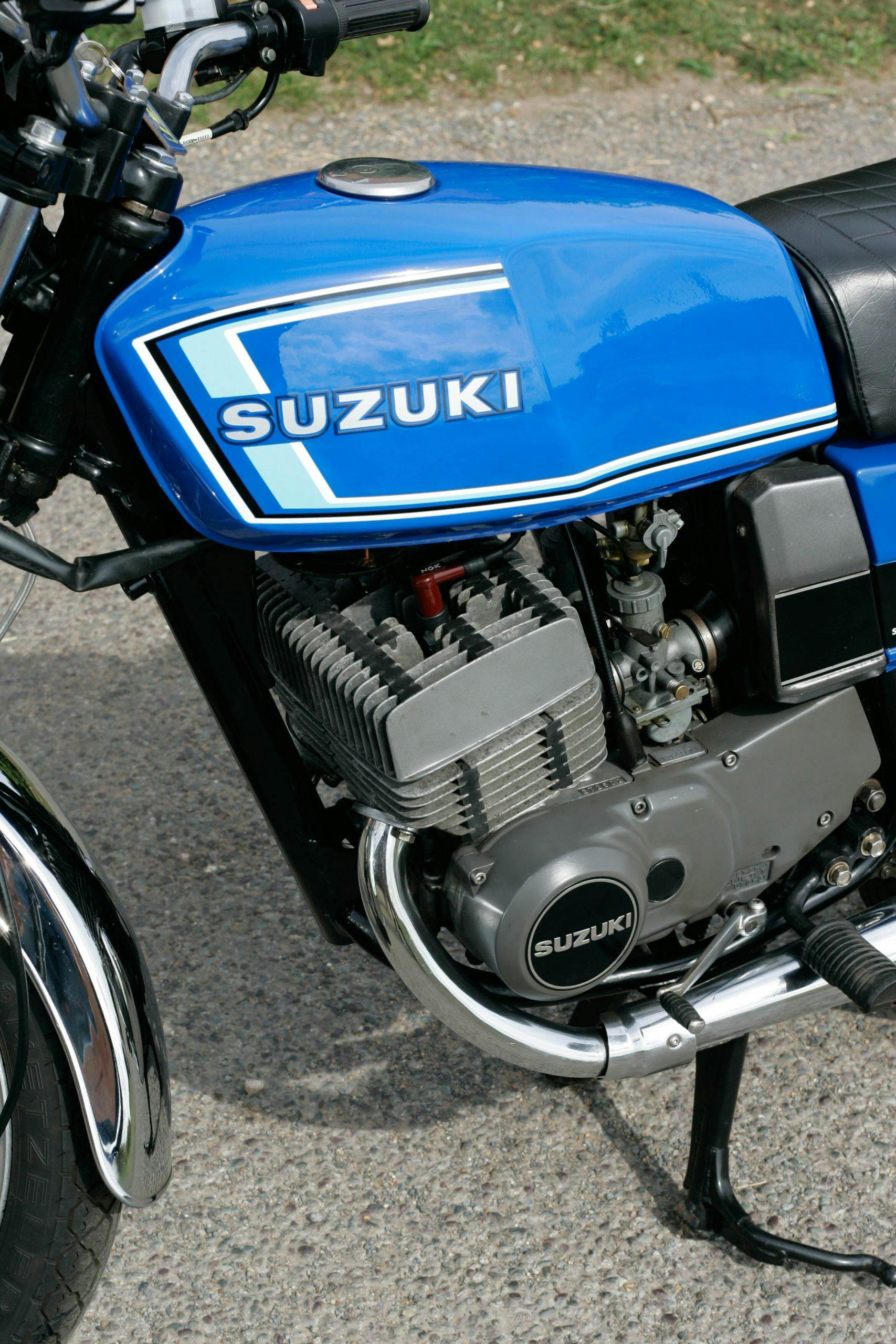

The weight savings were all in the chassis. A new tubular steel frame made do with one downtube instead of two. Lightweight cast aluminum wheels replaced the old wire-spoked ones, and the front disc and rear drum brakes were smaller. A more angular gas tank and side panels freshened up the styling.

On climbing aboard this nicely preserved blue X7, I was surprised to find it seeming bigger than I’d expected. Even this raciest of two-strokes had a fairly wide and well padded dual-seat, and felt like a proper motorbike as I leaned slightly forward to grip its fairly wide, near-flat one-piece handlebar.

A gentle swing of the kickstarter fired up the engine with a crackling, nostalgic two-stroke exhaust note—”the scrunching of broken glass being shaken in a thermos flask,” according to one contemporary tester. Once underway the X7 had enough straight-line speed to make it fantastic fun, provided I kept it revving hard by repeatedly stirring the six-speed gearbox.

The action didn’t begin until 5000 rpm, when the motor suddenly came alive to send the bike leaping forward, a slight trail of smoke sometimes visible in the air behind. From then on the lightweight Suzuki was quicker than the similarly powerful but heavier RD250.

Apart from the need for frequent gear-changing to keep it near the 8500 rpm redline, the bike’s only real drawback was that in the all-important zone above 5000 rpm the engine felt slightly buzzy, especially through the handlebars, which were solidly mounted.

That vibration didn’t encourage me to thrash the little engine, but the X7’s performance certainly did. Provided it was kept revving it screamed rapidly to over 80 mph and could sit at that speed in top gear with the tach indicating 7000 rpm.

With its rider’s chin—or, alternatively, the chin piece of a polycarbonate full-face lid—on the tank the little twin was good for a genuine 95 mph, even with mirrors in place. So although it really required a hill or tail wind to get to 100 mph (those magazine top speeds were one-way figures), it was definitely capable of spinning its optimistic speedometer’s needle to the three-figure mark on the dial.

Handling was as light and lively as the bike itself. The X7 was more flickable than the RD250, if not the Kawasaki KH250 that was arguably the sweetest steering of the learner-legal brigade. But that agility came at the expense of a slightly nervous feel that occasionally turned into full-blown instability.

Contemporary testers rated the handling as distinctly marginal. “It’s the combination of naked, unashamed power and a light chassis with quick steering,” wrote one. “Thrashing around some of our favorite back-tracks the front end of the X7 was constantly going light, twitching and flicking this way and that under full bore power.”

I was slightly surprised to find the X7 didn’t seem all that nervous, although its handling was hardly likely to have improved over the decades. Perhaps its relatively modern Metzeler tyres helped, though. Or maybe I just didn’t ride it as aggressively as I would have done when the bike was new and I was a teenager in a hurry.

If I had got into trouble I’d have been glad of the very adequate brakes. The Suzuki’s tiny front disc pulled it up respectably hard, and the diminutive single-leading-shoe rear drum added some useful assistance.

The X7 deservedly sold very well and was still in Suzuki’s range in 1982, its only changes the paintwork’s fresh pinstriping plus a few details including instruments, switchgear, mirrors, and indicators.

But by then it had suffered a double blow: the arrival of Yamaha’s RD250LC, whose liquid-cooled engine gave a definite edge over the aircooled Suzuki; and the new law that put that generation of thrilling 250cc two-strokes out of reach to learner riders.

An era of quarter-liter competition was ending, and X7 production would soon follow. Being a motorcycle-crazy 17-year-old would perhaps never be quite so much fun.

***

1978 Suzuki GT250 X7

Highs: Lively engine, agility

Lows: Peaky engine, instability

Summary: Teenage hooligan’s dream

—

Price: Project: $1900; Nice ride: $4700; Showing off: $8500

$5850 (#4 condition, Fair) – $9750 (#1 condition, Concours)

Engine: Air-cooled two-stroke parallel twin

Capacity: 247cc

Power: 29 hp @ 8000 rpm

Weight: 128 kg without fluids

Top speed: 95 mph

Hello,

I have also a well restored X7, and I will mount a high handlebar.

Do you have any idea to get an original one ?

best regards Martin