Media | Articles

This third-generation exhaust fabricator is helping save Britain’s classic bikes

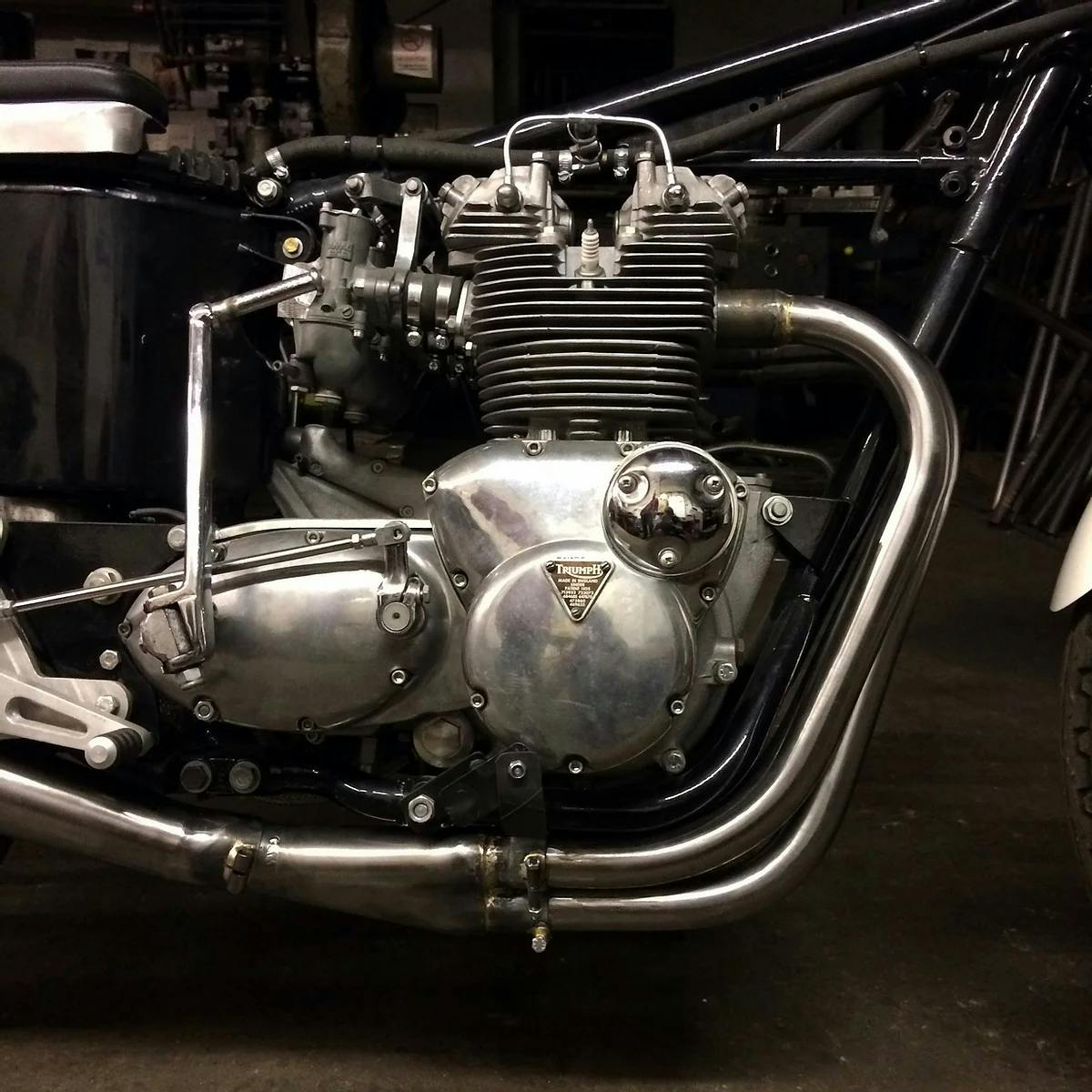

Leading down a cobbled alleyway hidden behind rows of brown stone terrace houses sits Raysons workshop on the outskirts of Rochdale, Lancashire, U.K. Were it not for the bright blue wooden doors and signage of the garage, you could easily imagine you’d stumbled onto the set of an industrial-era period drama. Open the door and the sensation of a bygone age grows. The garage is part of a mill originally built in 1800s, and it’s here that Ben Hardman—a third-generation exhaust fabricator—keeps alive the skills that may just save Britain’s classic motorcycles.

Inside the workshop, the comforting smell of oily engines lingers in the air. Exhaust pipes dangle from every available rafter of the workshop ceiling. Old lathes, milling machines, and workbenches cover almost every inch of the cold concrete floor. Sitting cross-legged in the middle of the room, fettling away on an old bike with a mug of tea close to hand, is Hardman.

The working environment is captivating. A large portion of the walls are covered in framed photos of his dad racing or working on bikes. Tools inherited from his granddad are scattered all over. Machines dating from well before Hardman was born line the floorspace, one of them from World War II with a plaque stamped “Property of the Air Ministry”.

His craft, skill and knowledge of motorbikes—British bikes especially—runs deep in the family. Hardman’s grandfather, Peter Lee, had his own bike shop in Rochdale, called Unity Equipe. It specialized in British bikes, particularly the Manx Norton, and regularly had to fabricate and bend pipes for customers. Hardman’s father Ray (Peter’s son-in-law) was a keen road racer, regularly competing throughout the ’80s and ’90s. He often worked with Peter to produce exhausts, and he had his own business, Unibend, using the same workshop in which we now stand. However, in 1997 Ray died in a racing accident at the famous Olivers Mount road racing circuit in Scarborough.

Despite the fact that Ray was unable to pass on his knowledge and fabricating skills, he had left his son a legacy of tinkering and a love of engineering. It was ingrained from a young age, with weekends spent in the paddocks of the nation’s race tracks.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Surprisingly, when Hardman first showed an interest in fabricating exhausts for classic bikes in his twenties, his granddad wasn’t keen; he worried it wouldn’t make him enough money. Even his father’s old friends try to dissuade him from the classic scene. “All my dad’s mates said, ‘You want to do [Japanese] bikes, they’re the next big thing; ’70s stuff is coming up, you wanna do two-strokes,’ but I just didn’t want to do ’em,” Hardman says. He stuck to his guns, though, and thankfully the classic motorcycle scene has grown in popularity in recent years—especially British bikes.

Hardman learned the craft beginning in 2008, and it wasn’t long before his granddad gave in and taught him the art of pipe bending. He’s become an expert in the field of exhaust pipes and it’s a fascinating sight to see him manipulate the steel pipes into precise, complex twists and turns using little more than a vise, torch (to heat and soften the steel) and his own bodyweight. He leans against the tubing, making fine adjustments.

Despite having been in the business for more than ten years and making a name for himself, Hardman’s still keen to push himself and learn new techniques. One process that I still can’t get my head around is hydroforming. He shows me a “megaphone” exhaust; it looks like a swollen pipe, kind of like the expansion chamber on a two-stroke. To create this effect, Hardman welds two flat pieces of steel together and pumps water between them at high pressure (with a tap to let any air out) until the steel swells into a hollow cylinder. After knocking out any dents and polishing out the welds, the finish is seamless and the pipe looks more a piece of modern art than it does an exhaust.

Hardman believes in ensuring his work is faithful to the era and style of each of client’s bike. He point’s to a pre-war bike, looking as though it’s just rolled out of a museum. “That’s a 1929 Humber that the owner found in a shed. I’ve got that style now where I can make them a bit rough, so they fit in.”

“So they fit the patina?” I ask.

“Yeah, just by hand-making them, I know how to make them look handmade. Rather than just a bent piece of pipe.”

Hardman achieves this effect using techniques and tools that both his granddad and father would have used. “I’ll sandbend that,” he says pointing to the Humber’s exhaust sitting on his workbench, “and braze instead of TIG welding it. Everyone’s got a TIG welder now, so they can TIG weld absolutely everything. I’ll braze or gas weld, depends on what it is really. Different jobs for different things.”

A BSA Scrambler sits in the corner, looking as though it’s come straight out of a showroom 50 years ago. “That looks immaculate, that pipe does,” says Hardman. “It’s currently at the chromer’s. But still it has to look a little bit rough—to make it perfect it’s got to be imperfect. That’s what makes these look dead nice, they’re slightly imperfect.” It’s all part of the tailor-made patina that a craftsperson like Hardman is able to bring to the classic bike community.

As you’d expect from the classic motorcycle scene, a mix of styles and genres of bikes pass through the wooden doors of Rayson’s workshop, ranging from BSA scramblers to Seeley race bikes. Of all the classics he works on, what’s his favorite, you ask? “Road racers,” says Hardman, in his thick Lancashire accent. “Yeah, they’re just nice aren’t they—and you get to see them race afterwards. I like to watch the scrambler bikes race but it’s just not as competitive.’”

He expands on his admiration for the racers: “Whereas the road racers take it proper, proper seriously. It’s their lives, that’s all they do. It all gets proper serious in road racing.”

One of the most impressive and modern race bikes he’s worked on in recent years is the rare Norton Rotary. Hardman was asked to build an exhaust system for the Wiz Norton Racing team, which rider Josh Brookes would use to compete at the Isle of Man Classic TT. It was a dream commission.

With a grin on his face, he tells me how he leapt at the chance to fire up the unique sounding rotary in the alleyway outside the workshop. “It sounded like a Formula 1 car, I was like, ‘Honestly we might have to kill it because someone’s going to call the police!’ Just had it running for a few minutes—it was proper loud!”

For this talented exhaust fabricator, work is more a passion than a business. You sense the importance of family, the handing-down of traditional skills, and the enthusiasm for the motorcycling scene that, dare we say it, you do not get when dealing with off-the-shelf suppliers. “Character, that’s what it is—character. Bikes need a bit of soul.” And need people like Hardman to keep feeding that soul.