Media | Articles

The Triumph Silver Jubilee Bonneville’s reign was short-lived

Triumph’s promotional film for the 1977 Silver Jubilee Bonneville was a classic that still resonates today. A middle-aged former biker, having abandoned motorcycles to mortgage, marriage and kids, catches sight of the Bonnie on TV—and something snaps.

He leaps up, digs out his old helmet, goggles, and riding jacket, and rushes out to blow the contents of his building society account on a silver 750cc Triumph. Moments later he’s cruising down the road, huge grin on his face, totally rejuvenated by the best of British biking.

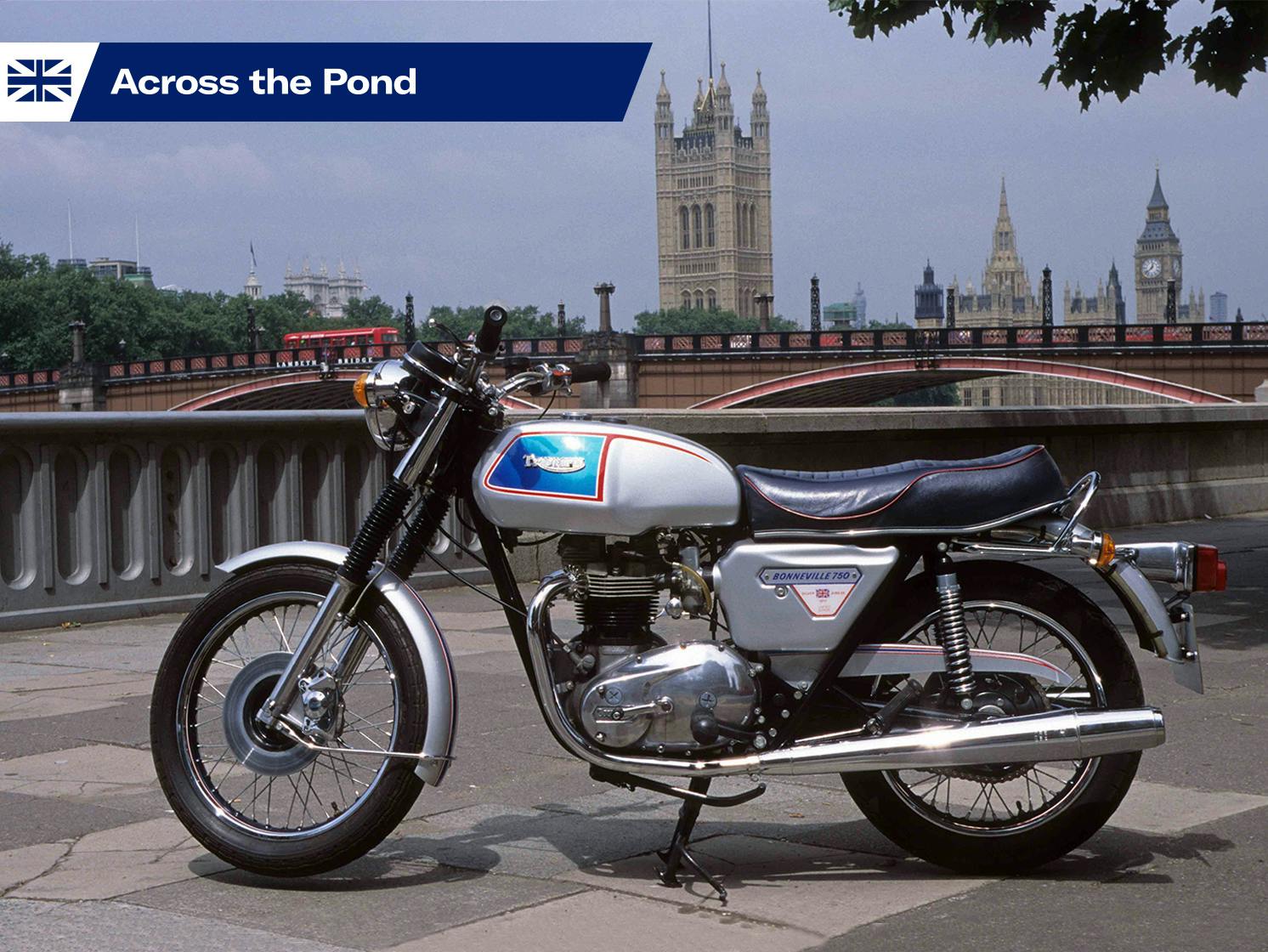

This year’s Platinum Jubilee pageant, celebrating the reign of Queen Elizabeth II, is another 45 years on, but the Silver Jubilee Bonneville still shines brightly. Cruising through tranquil Surrey countryside, with the parallel-twin motor delivering torquey low-rev performance and the soft, deep exhaust note providing a stirring soundtrack, the Triumph highlights the appeal of classic British motorcycling.

Before I’m accused of viewing the Bonneville through rose-tinted goggles, I’ll add that it had earlier annoyed me with several ailments, ranging from leaks to a notchy gearbox. Compared to Japanese rivals led by Suzuki’s fast and fine-handling GS750 four, which was released in the same year, the Bonneville was old when it was new. But if the limited-edition model that Triumph created to honor Queen Elizabeth’s quarter-century on the throne had its faults, it also had plenty going for it.

Back in 1977, creating a special Bonneville to mark the Silver Jubilee offered a welcome sales opportunity to a firm in terminal decline. In those days, Triumph’s factory at Meriden, in Coventry, was being run by the workers’ co-operative that had taken control after a sit-in that had begun four years earlier, following management plans to shut the loss-making factory and move production to BSA’s plant in Birmingham.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

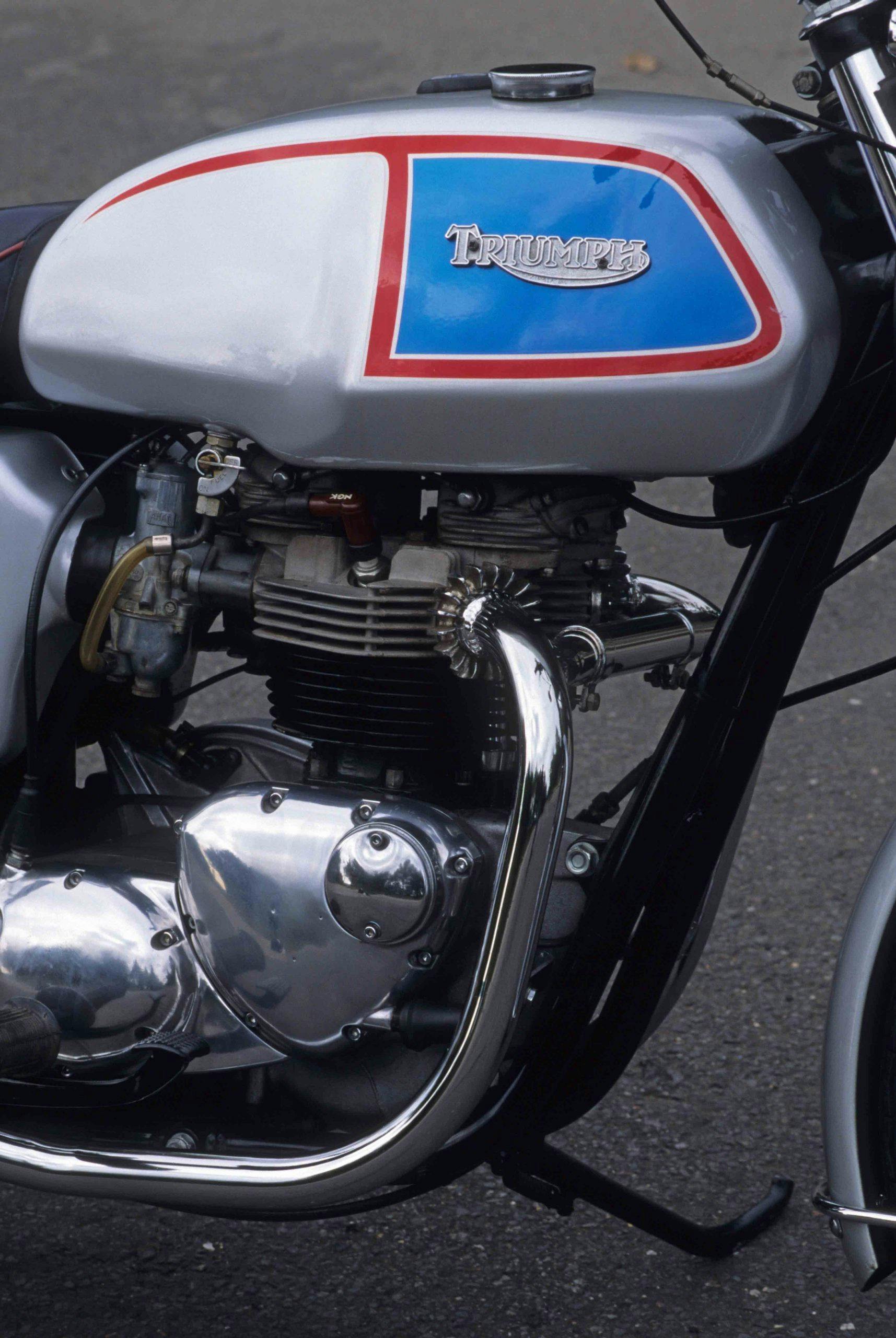

The Jubilee bike was essentially a cosmetic update of the standard T140 Bonneville, the 744cc, twin-carburetor roadster that dated back to the original 650cc T120 Bonneville of 1959. Its main feature was the special silver paint scheme with red, white and blue highlights, plus extra chrome on parts including forks, engine covers, and rear light.

The seat was blue with red pinstriping; and the wheels, which were originally fitted with Dunlop Red Arrow tires, featured red, white, and blue rims. Like the standard Bonnie, the Jubilee was built both in U.K. and American export spec, the latter with higher bars and smaller fuel tank. It came with a signed certificate of authenticity from Triumph, and with approval from Buckingham Palace.

This well-preserved U.K.-market model felt light and compact as I threw a leg over its seat; not surprising given its weight of just 187 kg (412 pounds). After I’d turned on the ignition near the left headlamp bracket and applied the carb-mounted choke, a gentle kick (no electric boot to help here) was enough to fire-up the motor, which came to life with a muted but pleasant twin-cylinder exhaust note.

First impressions were mixed. The combination of slightly upturned bars, forward-set footpegs and thick dual-seat was comfortable in town, and allowed a slight crouch into the wind that made higher speeds painless on more open roads. The motor pulled well at low revs but felt woolly in the midrange and wouldn’t rev out—until I realized the choke was vibrating partly shut.

Tightening a screw with a coin (a period accessory these days) cured that problem and the Triumph then ran much better, still hesitating slightly at about 55 mph in top gear before clearing to pull strongly until the inevitable parallel twin vibration began to intrude. Peak output was a claimed 52 hp at 6200 rpm, giving a top speed of just over 110 mph. At an indicated 75 mph the Bonnie was reasonably smooth, but upping the revs increased the buzz through seat and footpegs.

The motor lost marks in a couple of other ways, too. After stopping to top up with petrol I was less than impressed, though hardly surprised, to notice several black oil spots under the engine. Shortly afterwards I was miffed to find petrol soaking the right leg of my jeans, thanks to a leaky filler cap.

Another irritation was the gearchange, which was horribly notchy. Many enthusiasts reckon Triumph’s left-foot change was never as good as earlier right-footers, but most T140s (including the two I’ve owned) shift much more smoothly than this one, which required a firm left boot.

There was very little wrong with the handling, which in ’77 was good enough to let the Triumph keep up with all but the hardest ridden opposition, at least on a twisty road. Stability was excellent and the steering, although heavy by modern standards, allowed the Bonnie to be flicked around with satisfying ease.

This bike’s forks felt slightly harsh despite the rubber-mounted bars, but the simple Girling shocks gave an impressively plush ride. The narrow rubber gripped fine, and the single disc brake at each end worked pretty well although the front lacked feel. Thankfully I didn’t have the chance to discover whether the old problem of delay in wet weather was still an issue.

Such tribulations were frequent back in 1977, and didn’t prevent the Silver Jubilee Bonneville from being a success for ailing Triumph, despite costing £1149 to the standard T140’s £1012. The firm had planned a limited edition of 1000 bikes for the U.S. market, plus 1000 for Britain and elsewhere, and had to build an extra 400 machines in November to satisfy demand.

But although the Jubilee’s sales helped make 1977 a promising year for the Meriden co-op, the workers’ optimism proved misplaced. Shortly afterwards, the weakening dollar was partly responsible for a sales slump in Triumph’s vital American market, while debts continued to rise. Production was drastically cut; more workers were made redundant. Although Meriden struggled on long enough to introduce electric-start and eight-valve versions of the Bonnie, the end finally came in 1983.

Since then, of course, John Bloor has made Triumph great once again, while Queen Elizabeth has continued majestically on to her 70th year on the throne, albeit with a few family-generated bumps in the road. A new-generation Platinum Jubilee Bonneville would surely be well deserved.

***

1977 Triumph T140 Bonneville Silver Jubilee

Highs: Regal charm and poise.

Lows: Vulgar vibes and leaks.

Summary: A stylish Seventies souvenir.

—

Price (in U.S.A.): Project: $4500; Daily rider: $7200; Showing off: $10,000

Engine: Air-cooled parallel twin

Capacity: 744 cc

Power: 52 hp @ 6200 rpm

Weight: 412 pounds without fluids

Top speed: 115 mph