Media | Articles

Supernova: The brief, bright life and death of the Harley V-4 Nova

Harley-Davidson has been trying to broaden its appeal of late, with a new family of liquid-cooled V-twins including the Pan America adventure bike.

Cynics will tell you that Harley should have revamped its range decades ago, rather than sticking to its traditional V-twins for so long. What’s less well-known is that the firm did develop a promising V-4 way back in the early 1980s, only to scrap the project.

The Nova was top-secret back then but was belatedly revealed more than 25 years later, when a prototype was displayed in the factory’s new museum in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

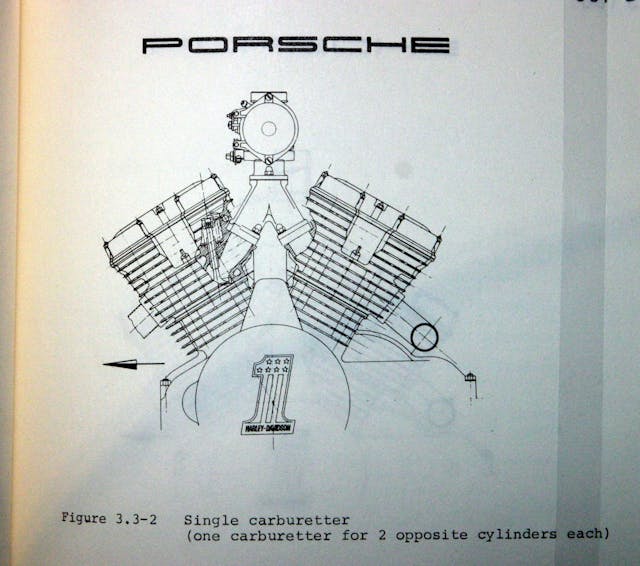

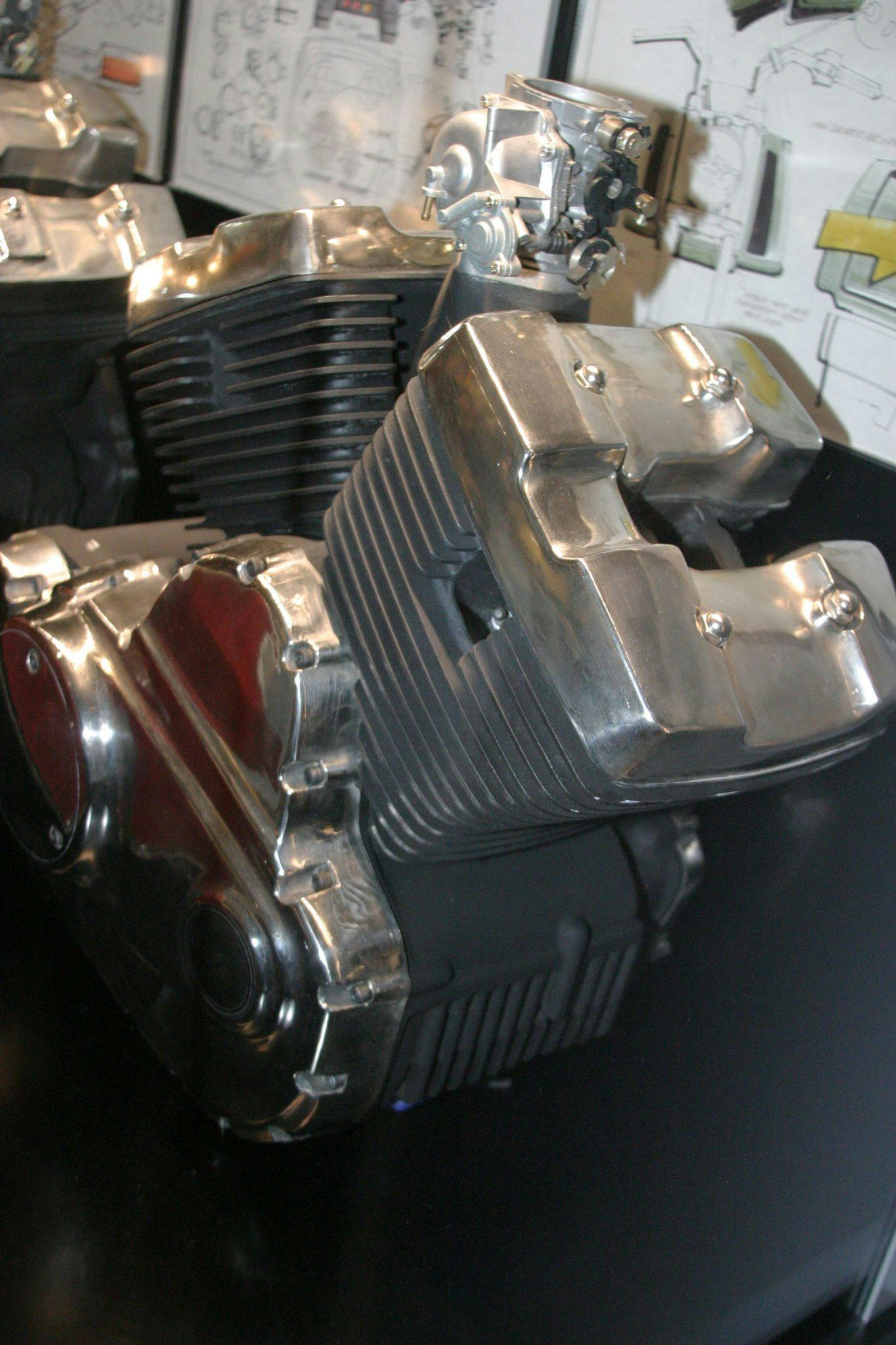

At first glance, the big, grey, half-faired Nova looked like just another member of Harley’s V-twin touring family. But its engine, developed in conjunction with Porsche, was an 800-cc, liquid-cooled V-4 with twin overhead camshafts and cylinders spaced at 60 degrees rather than the familiar 45.

In 1981, when the Nova was due to be launched, it would have predated Honda’s successful VF and VFR families of V-4s, and would have been as advanced as any bike on the market. In fact, Harley planned a six-strong family of Novas, ranging from 400-cc V-twin and 1000-cc V-4 to a 1500-cc V-6. All would have featured many shared parts under a modular format similar to the one that Triumph would adopt on its rebirth a decade later.

The Nova project was hatched in secret meetings that Harley’s top management and engineers, led by vice president Jeffrey Bleustein, held in the late 1970s, to establish a plan for the following decade. They decided to invest in two directions: a family of bikes powered by an updated, air-cooled V-twin engine, eventually known as the Evolution; and an all-new, high-performance line with a more advanced, liquid-cooled powerplant—the Nova.

“At the time, we thought Harley needed a new range, to complement rather than to replace the V-twins,” recalled Mike Hillman, the English-born engineer who was chosen to lead the Nova project. “Emissions and noise regulations were getting tighter and we weren’t sure we could make the air-cooled engine meet them. The Japanese manufacturers were swamping the market with different products, and we wanted something to compete.”

Harley’s parent company AMF (American Machine and Foundry) was keen to support the ambitious project, but developing such an advanced, all-new engine alongside the updated V-twin would have stretched R&D resources too thin. “We looked at quite a few suppliers and went to three in particular: AVL in Austria, Riccardo in England, and Porsche. We chose Porsche partly because they had experience of production as well as development,” Hillman said.

A 60-degree Vee angle was chosen, partly because Hillman, who before joining Harley had designed a Formula 1 race car for Brabham in the 1960s, wanted to use the powerplant as a stressed member of the chassis. A contra-rotating balancer shaft allowed the unit to be solidly mounted to the pressed-steel backbone frame.

The engine’s modular design retained a common stroke of 58 mm and used alternative bore sizes of 66 and 74mm to produce individual cylinder capacities of 200 or 250 cc. This gave V-twins of 400 and 500 cc; V-4s of 800 and 1000 cc; and V-6s of 1200 and 1500 cc.

“We started with the 800, which might not seem the most logical choice, but we wanted to get into the 750cc class,” said Hillman. The relatively short stroke allowed a redline at 9500 rpm. Carburetors were used initially, although fuel-injected engines were also planned.

Power output was about 100 hp per liter, which would have given the 800-cc Nova 80 hp – competitive with Honda’s first V-4, the VF750S, which was launched in 1982 with a claimed 79 hp. Harley considered using shaft final drive, before opting for a toothed belt.

Following pressure from styling chief Willie G. Davidson, who wanted a clean look, there was no place in front of the V-4 unit for a conventional radiator. Instead the rad was placed almost horizontally under the seat. A fan drew cooling air through the radiator from the dummy tank, which was in fact a large airbox and was itself fed via two large scoops at its front. The fuel tank was also under the seat, straddling the radiator; its cap was in the tailpiece.

All this resulted in bulbous side panels but a low center of gravity. Even so, the naked Nova had a fairly lean, sporty look, despite its raised bars and stepped seat. Suspension was by conventional telescopic forks and twin shocks.

Development through 1979 and 1980 went well, with Hillman leading a 15-strong team in Milwaukee, and 15 more engineers working at Porsche. More than a dozen prototypes were built, all with 800 cc capacity—some naked and others with bodywork.

Testing took place both in the States and in Germany. Harley had previously used public roads for reliability testing, but the need for secrecy led the company to set up a private facility in Talladega, Alabama.

The Nova was certainly promising, combining 120-mph performance with reasonably light weight and, according to Hillman, excellent handling. “It was very nice to ride because the frame was so stiff. The chassis drove fabulously and the brakes worked very well. I rode the bike but mostly it was the test riders’ job. We had to keep the numbers down due to the project’s secrecy. There was one exposé when someone took photos in Germany, which were published by Motorrad magazine. But not much information escaped.”

The Nova project seemed to be moving steadily toward its projected launch date of mid-1981—initially in unfaired 800-cc form, to be followed soon after by the 1000-cc version. Touring, sport, and even super-sport V-4s were planned for future years, followed by the V-twin and V-6 models.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Sadly, for all those who would have loved to see high-performance Harleys emerge to take on the Japanese, it didn’t happen. The year 1981 turned out to be a landmark in Harley-Davidson history, thanks not to a dramatic new model but to the management buyout from AMF that kick-started the marque’s spectacular revival.

President Vaughn Beals and other bosses of the reborn firm, which was heavily in debt, had to choose between continuing to develop the Evolution V-twin or producing the Nova. Inevitably, the safer option of the aircooled V-twin won. The Nova project was abandoned, after several years of development, more than $10 million of investment, and tens of thousands of miles of testing.

Even then the Nova refused to die.

“In ’82, the company made its first-ever financial loss, but in spite of that the management still siphoned off a chunk of money to keep the Nova going,” recalled Hillman, who joined Beals in making presentations to firms in the United States and abroad, in a search for financial support for the project. “In fact, we found a place to build it, in Italy. But strategically it didn’t make sense. Then bike sales fell towards the late ’80s. By then it was less competitive anyway.”

Finally, Harley execs made the tough decision to abandon the Nova, and the prototypes were either scrapped or put into Harley’s warehouse. According to factory insiders at the Harley-Davidson Museum, five bikes remained, of which two were runners. The display bike is a non-runner incorporating some parts made from wood.

Hillman went on to enjoy a successful career at Harley, rising to vice president and using his Nova connections to help set up the deal that saw Porsche develop the liquid-cooled V-twin engine for Harley’s V-Rod, released in 2001.

“It was a shame Nova didn’t make it, but you have to move on,” he said. “I’d like to think it would have augmented the V-twins. But the investment Harley made in getting the factories to work properly at that time, and the focus on improved quality with the Evolution models, were vital to the company’s growth. Scrapping Nova was undoubtedly the right decision.”

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

I was Mike Hillman’s choice to head of the US engine work with the goal of putting it into production. I have domestic crankcases tooled and ready for production. I worked verifying things with engines in our dynos in Milwaukee. Mike as a great boss and it was a great project.

V-6… That would have been really interesting.

And to everyone who thought AMF was bad for HD, keep in mind that in all likelihood that Harley-Davidson would probably be nothing more than an historical footnote after ceasing operations in the early 70s. Not only did they offer financial stability but they did some serious heavy lifting in improving manufacturing efficiencies as well as ‘evolving’ its underlying design, keeping the original but better.