Media | Articles

Stock Stories: Ariel Square Four

With custom-bike culture exploding in recent years, the history and importance of early two-wheeled machines are often overlooked. Stock Stories tells the tales of these motorcycles.

Edward Turner is well known to the classic motorcycle fraternity as an ace motorcycle designer, primarily for his work during the golden age of Triumph. For this installment of Stock Stories, we’re going back to his first forays into engine design. These were by no means humble beginnings—from the start, the man who helped define the classic British motorcycle thought outside the box.

Turners first public venture into motorcycle design came in 1927, when he was 24. Engine drawings for a bike later known as the Turner Special appeared in an issue of the magazine The Motor Cycle. Turner’s work showed a single-cylinder powerplant whose overhead camshaft was driven by an arrangement of gears. Shortly after the magazine saw print, Turner decided to revise his design; the new layout used bevel gears driving a vertical shaft that fulfilled the role of a camshaft.

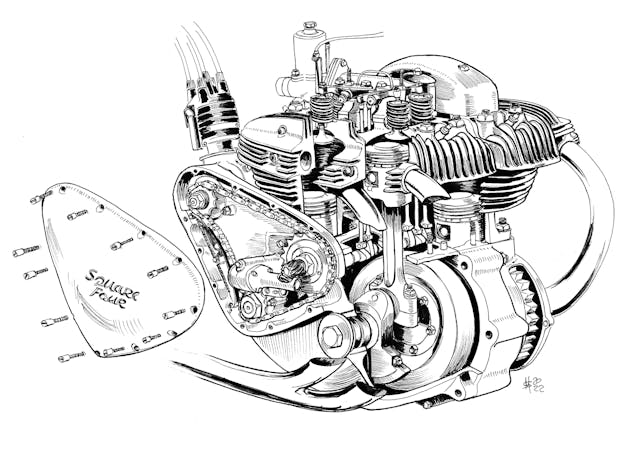

It’s not surprising that Turner saw the value of using a bevel drive. He was at the time running a Velocette dealership called Chepstow Motors, and Velocette used a similar arrangement. But the work that would come after was far more ambitious and forward-thinking. Like many motorcycle engineers, Turner wanted to build an engine that combined compact size and good balance with ample power. By the end of 1928, he had penned a novel four-cylinder whose bores were arranged square, two-by-two. This formation was essentially two twin engines coupled in parallel, with the whole thing timed by geared flywheels sat in the center of the crankcase.

These flywheels ran in opposite directions, so the gyroscopic effect of their rotation was effectively canceled, aiding smoothness. Turner also arranged the engine’s timing so that its pistons hit top dead center on diagonally opposite sides. Because no pair of cylinders was never allowed to fire on the same side of the engine, forces were evenly distributed front-to-back and left-to-right.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Turner is said to have approached various marques about producing his new engine, including BSA, but if these meetings happened, they were dead ends. With economic pressure looming—it was the late 1920s, after all—Ariel Motorcycles director Jack Sangster saw potential in Turner’s work. The engine’s compact dimensions would allow it to be installed into existing Ariel frame designs and use mostly stock ancillary components, saving the cost of engineering bespoke parts. In 1929, Sangster set Turner to work overseeing production of a running prototype in concert with the legendary Burt Hopwood, under the supervision of Val Page.

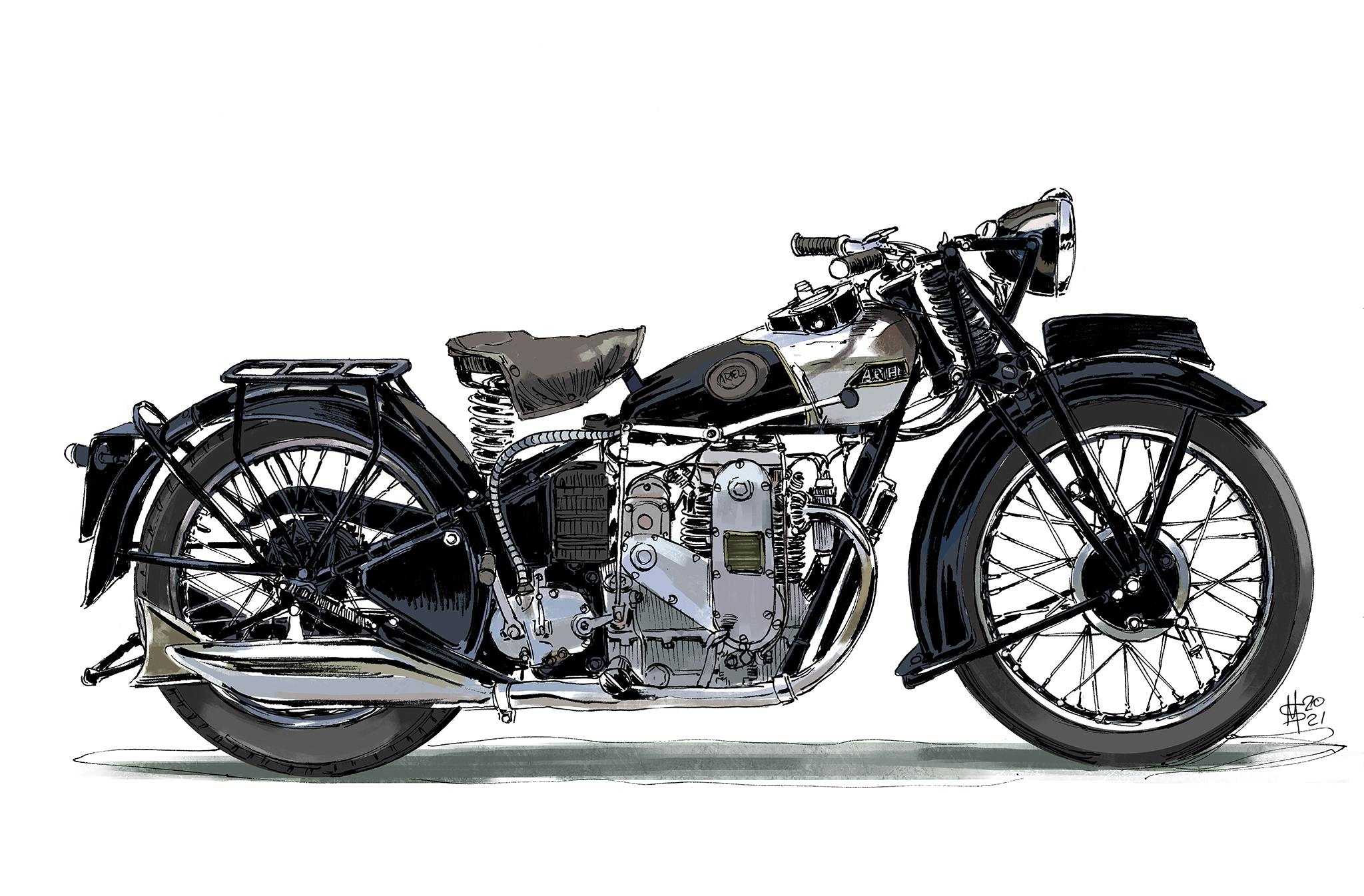

The Square Four was designed for a capacity of 498 cc, so those men used Ariel’s Sloper model, a 500-cc machine, for the rest of the bike’s parts. A prototype engine was built in time for the 1930 Olympia motorcycle show, where the Square Four starred, receiving more attention than even the revolutionary Matchless V-four-equipped Silver Hawk. The first production Square Four model was christened 4F.31 and can be seen at the top of this article. The keen-eyed reader will notice the hand-operated gear change, which featured on the Olympia prototype machine and other early 4F.31s. (The bike switched to a foot change the first year of production.)

On its release in 1931, the 4F cost £75 10s. The bike was well received by the press; the test ride published in The Motor Cycle noted that the Square Four was easy to start, with great acceleration, top speed, and road-holding. On top of this, the engine was nearly silent at idle. Ample low-end torque allowed the bike to easily pull away from a stop in second gear, and the editors discovered a fuel economy of 64 mpg at 50 mph. To add to this positive press, a Square Four sidecar rig earned a gold medal in the famed London to Lands End Trial, proof of real performance and reliability. As Ariel was aiming the Square Four at families and commuters, this bode well.

Ariel built 927 4F machines between 1931 and 1932—healthy sales for a new multi-cylinder motorcycle in Thirties Europe. Nor was the bike ignored by the speed crowd. In 1933, Ben Bickell took a supercharged, 498-cc 4F to Brooklands and attempted to cover 100 miles in an hour, pursuing a record. The bike saw consistent speeds of 110 mph in testing, but official attempts ended with either the cylinder head blowing apart or the cylinder’s base flange trying to escape from the block. Ariel’s Ernie Smith sought factory permission to make a stronger cylinder barrel for the attempt, but Turner insisted that the record could only be genuine with a standard engine. That same year, the 498-cc 4F was phased out; the recently launched 601-cc Square Four was deemed better for touring and sidecar hauling.

Whilst Bickell’s supercharged attempt was an extreme example of engine testing, the major problem with the engine was overheating rear cylinders. In addition to being shrouded from cool air, the rear pistons gained heat from the front cylinders. By 1936, Turner had become Ariel’s general manager and chief designer, and he made sure that efforts were made to solve the cooling issue, in order to secure the Square Four’s reputation as a reliable touring machine.

Val Page was tasked with redesigning Turner’s work. Page added cylinder fins and cool-air channels around the engine, and he reengineered the valvetrain, switching to a single camshaft and short pushrods. All these changes achieved greater reliability and performance in an engine that had already proved itself to be a durable and smooth powerhouse.

Consumers got their hands on the Val page engine in 1937 when the 1000cc 4G model was released, with the 4F being phased out by the end of the year. The Square Four continued to be a staple of the Ariel stable going into 1939 when they introduced an optional plunger style rear suspension that would be fitted as standard to all Square Fours after World War II.

Production paused for World War II, but the bike reappeared in 1945, now with telescopic forks. It changed little until 1949, when the engine underwent vital modernization: Barrels and heads were now cast in aluminum, reducing weight and aiding cooling.

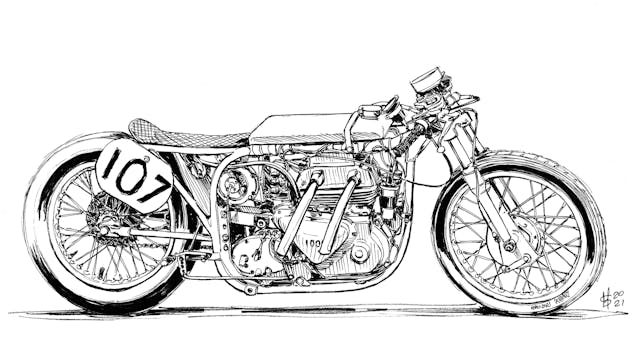

The Square Four was now capable of 90 mph from a power output of 35 hp at 5500 rpm. This kind of sporting capability and pulling power proved attractive for family men with an eye for speed. One such customer was frequent Ace Cafe customer Dennis Norman, who met his wife Patricia on a blind date at that infamous venue. In lieu of an engagement ring, the couple bought a Square Four. In 1959 Norman built a sprint motorcycle from the remnants of another, damaged Square Four, plus some findings from the parts bin of his repair shop in Hemel Hempstead. He mounted the unit into a Norton featherbed frame and fitted four rather loud megaphone exhausts. Norman campaigned this machine successfully for nearly a decade, eventually nearing a 10-second quarter mile after supercharging the engine.

The final incarnation of the Square 4, the Mark II, was released in 1953. This model included separate exhausts for each cylinder as well as a redesigned head, all in the name of cooling the engine as much as possible. Production continued until 1959, when Ariel killed all of its four-stroke machines in order to concentrate on the company’s popular two-stroke models.

The Ariel Square Four carved its own niche motorcycle market for more than 20 years. Its creator went on to help build Triumph, that most British of marques, into a powerhouse, but Turner’s first engine has more than stood the test of time.

***

Martin Squires has just released a 2022 calendar featuring his drawings of various motorcycles, many of which have been featured in Stock Stories. To order your own copy, click here.

Thank you for so many wonderful Stories on Classic MCs etc etc

Baz Taylor

Brisbane Australia

From the Land Down Under