Media | Articles

Honda Scramblers have been a hot new thing, for 50 years now

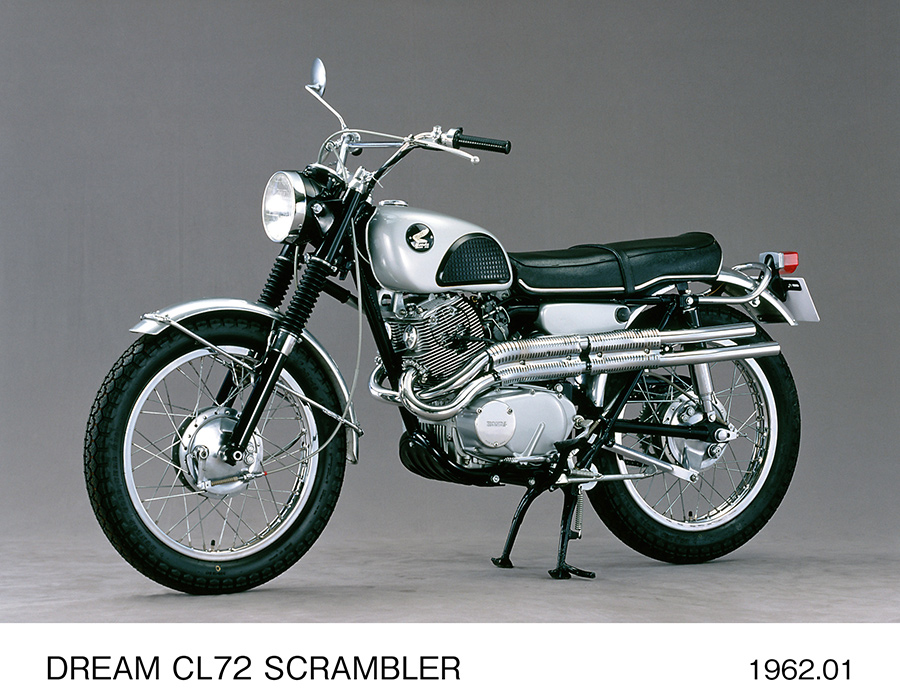

Squint hard at today’s dual-duty motorcycles and you may see a classic Honda Scrambler’s ghost. The idea of a practical street bike that could go almost anywhere has taken hold in the form of popular “adventure” models. But it’s their retro-stylish urban counterparts, equipped with high-mounted mufflers, hefty skid plates and cross-country tires, which have revived the romance of the rugged Scrambler look.

Honda’s 250cc CL72, sold in 1962-65, and its 305cc CL77 big brother of 1965-68, were the company’s do-it-all machines during the “bike boom” of the 1960s. The stampede for Accords and Civics was still years away, but Americans bought a total of nearly 90,000 of the two-cylinder Scramblers for weekday commuting — and then used them for weekend fun, on and off the road. While biased toward pavement duty with their modest 3 to 4 inches of suspension travel, they performed admirably on gravel roads and trails, where the going wasn’t extreme.

Most Scrambler buyers were smitten by the bikes’ racy upswept exhaust, peanut gas tank and cross-braced handlebar — the lean, archetypal “street scrambler” look. But they were also sold on Honda’s outstanding reliability, high-revving power and absence of oil leaks. The CL twins proved they could handle the rough stuff when, in 1962, the racer Dave Ekins and a Honda dealer, Bill Robertson Jr., rode two early production CL72s nearly 1,000 miles through the Baja California desert from Tijuana to La Paz. That record feat gave American Honda a bold advertising message that promised durability for all Honda models.

The promise was no idle boast. The single overhead cam engines, with their deeply-finned, sloping cylinders and 4-speed gearbox, had been well proven in street bikes like the 250 and 305 Dream Touring and the sporty CB72 Hawk and CB77 Super Hawk. The overhead cam twin is a willing revver, capable of over 9,000 rpm. To create the Scramblers, the Hawks’ twin carburetors were retained. Torquier camshafts were fitted, the compression ratio was lowered and the electric starter deleted.

Most Scrambler twins featured a 180-degree crankshaft firing order, but about 110 CL72s were imported with 360-degree cranks (both pistons rising and falling in unison) and different gear ratios. Their giveaway is “Type 2” cast into the ignition points cover, according to Mark Mederski, special projects director at the National Motorcycle Museum in Anamosa, Iowa.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The CL72 introduced Honda’s first full-cradle tubular steel frame, a departure from the company’s ubiquitous stamped-steel designs and from the non-cradle tube frame of the CB road bikes. The quality-built CL chassis, aluminum fenders and flanged 19-inch steel wheel rims “showed that Honda was serious about building a road-and-trail machine capable of competing with the Triumphs and BSAs of the era,” Mederski said. Brakes were single-leading-shoe drums on the 250s and upsized to more powerful twin-leading shoe binders on the 305.

Of the bikes, Mederski ranks the 250cc models as more collectible than the 305s, “To me the 250 Scrambler is as cool and collectible as an early CB750, and it’s overlooked,” he said.

Parts, including a few New Old Stock items, are available on eBay and at swap meets. Exhaust systems and sheet metal in good shape are increasingly rare.

“Find a good original or restored example and pay for it,” Mederski recommends. His prize CL72 can reach 80 mph, yet the aural appeal is the clincher: “It sounds so good — those straight pipes just wail!”

Honda CL72 and CL77

Engine type: Air-cooled SOHC parallel twin, 4-speed transmission

Displacement: 247cc (CL72); 305cc (CL77)

Claimed hp @ 9,000 rpm: 24 (CL72), 27.4 (CL77)

Top speed: 80-85 mph

Weight (dry): 315-319 pounds

Price new (CL77): $707 (1967)

I have had 13 of these bikes throughout the years, great bike!