Media | Articles

BSA’s 650 Lightning was good, but not enough to save the company

Although weights, measures, and currency are adjusted for a U.S. audience, colloquialisms and contextual references reflect this story’s origin on our sister site, Hagerty UK.

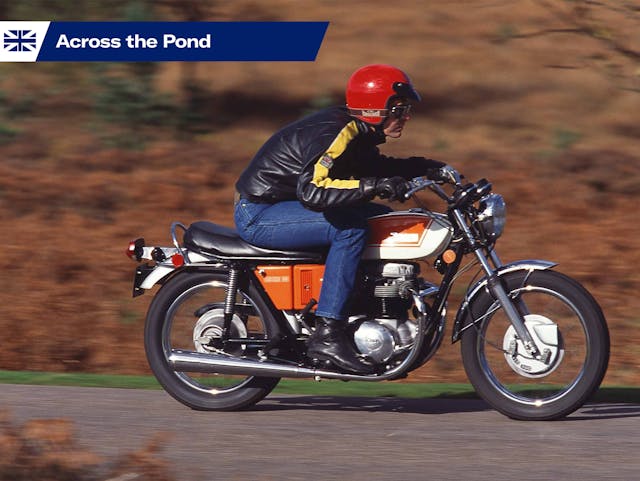

With the sun shining, the road ahead clear, and the 650 Lightning rumbling along in relaxed fashion, it’s hard to imagine what all the fuss was about. A touch of parallel-twin vibration coming through the seat and footrests doesn’t prevent the elderly BSA from seeming enjoyably brisk and utterly inoffensive, much like many British twins of the ’60s and ’70s.

But the Lightning certainly put a few backs up on its launch in 1971, when it was a controversial departure for BSA. The A65L Lightning had originally been released in the mid-’60s as the hotter, twin-carburetor version of the Birmingham firm’s A65 twin. This updated model, with its raised bars, small fuel tank, and minimalist chromed mudguards, was intended to add a bit of glitz for the important U.S. export market.

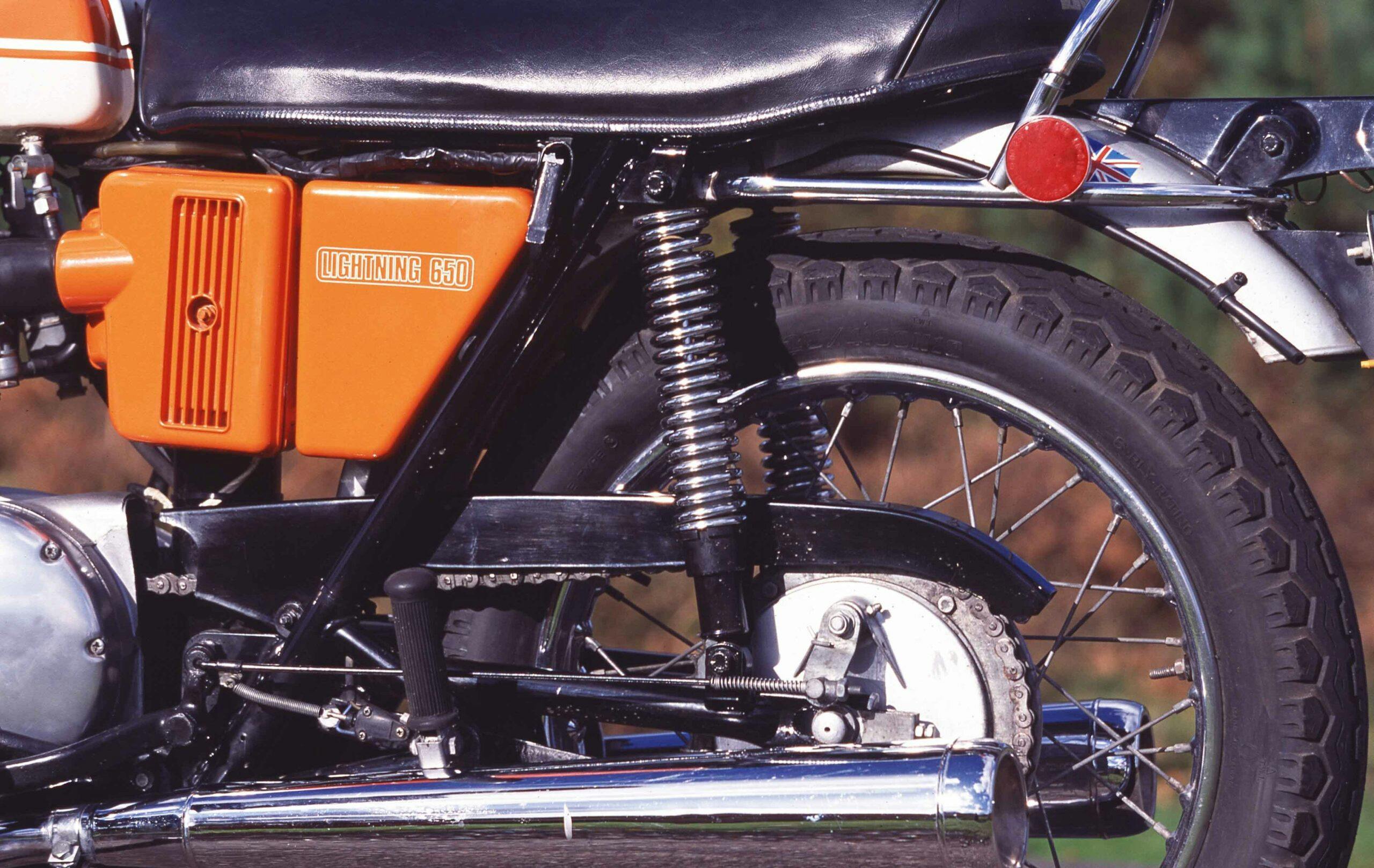

More importantly, this Lightning was the first with a new “oil-in-frame” chassis that was considerably taller than its predecessor’s. The redesigned frame had been specified by BSA’s management even though the factory’s development riders had warned that it was too tall, making the bike unmanageable for riders of average height or below.

It’s to be hoped that the recently revitalized BSA’s current Indian owners don’t make similar mistakes. And perhaps that their promotional activities are more restrained than those of their predecessors, who launched the Lightning and 15 other models in October 1970 at a London spectacular that became known as the ailing British motorcycle industry’s Last Supper.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The lavish bash at the Royal Lancaster Hotel off Hyde Park involved lunch and dinner for hundreds of guests, including government figures as well as press and trade from around the world. Top comedian Dave Allen and dance group The Younger Generation performed before the bikes were unveiled to a trumpet fanfare, each machine wall-mounted in its own giant three-dimensional picture frame.

This slick PR event contrasted with the chaos surrounding BSA, which was already in deep financial trouble. The 1971 season turned into a disaster, with production problems, striking workers, badly produced parts, and even a faulty computer that ordered a large supply of unwanted components. The Lightning itself was delayed and didn’t appear until late summer, missing much of the sales season.

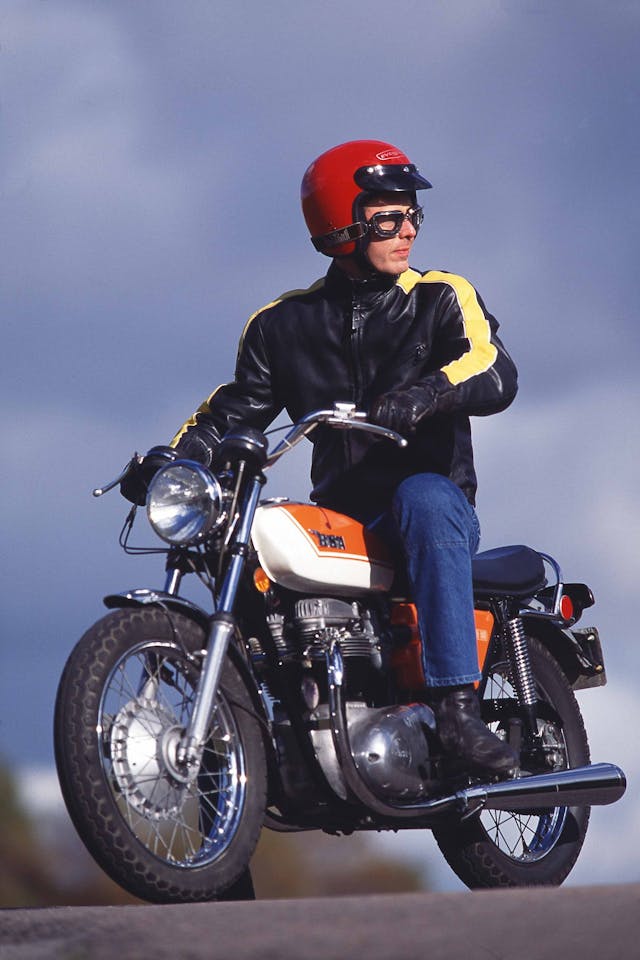

Although not everyone liked the look of the revamped Lightning when it finally arrived, the orange-and-white twin was given a generally favorable reception. With its high bars and small, 2.9-gallon tank it certainly looked more lean and modern than its predecessor, if less practical. The taller, 33-inch seat height was dictated by the dimensions of the new frame, which incorporated a large, oil-holding main spine.

At least the slim BSA was respectably light, at 419 pounds. Being tall myself, I was more worried about being able to start this aging twin, which hadn’t been run for a while. But after a few leaps on the kickstart it fired up with a restrained parallel-twin chuffing from its silencers.

BSA hadn’t done much to update the engine for 1971, having revamped the 654cc, pushrod-operated parallel twin the previous year with new parts including pistons and con rods, plus modified Amal carburetors. Maximum output was a claimed 51 hp at 7000 rpm, competitive with sister firm Triumph’s 650 Bonneville.

The bike I’m riding must have been restored at some stage because the ’71-model frame was originally painted not black but cream, matching the lower part of the tank. The view from the seat is clean and simple: the wide bars with their squashy grips, an alloy strip running along above the slim tank, and a pair of black-faced clocks either side of the chromed headlamp, with its trio of colored warning lights.

On a mild day the BSA is fun for gentle cruising on country roads. Its engine rumbles along lazily and fairly smoothly. Controls are light, and the four-speed, right-foot gear-change shifts sweetly. At that pace, sitting bolt upright with my feet on the forward-set footrests, I could see why BSA’s management must have thought that riders on both sides of the Atlantic would appreciate the Lightning’s laid-back looks and feel.

Things weren’t so rosy when I turned onto a wider road and wound the BSA up a little more. The elderly twin accelerated crisply enough from low revs, and showed enjoyable enthusiasm through the midrange. But by the time the rev-counter needle approached 5000 rpm the engine was sounding like a cement mixer, discouraging me from going much above 70 mph, let alone checking out the ton-plus top speed.

The combination of wind blast and typical parallel-twin vibration coming through the footrests would have made long distances at speed tiresome, but there is not too much wrong with the Lightning’s handling, which was rated excellent in its day—despite concerns over the height of that frame. Although I was wary of this bike’s ancient tires, the BSA could be flicked around easily using the leverage of those broad bars. Yet it is also stable through sweeping curves on the open road.

Despite its exposed riding position the Lightning is tolerably comfortable, too. The original forks and aftermarket shocks give a fairly firm ride, and are well-damped by early-’70s standards. This bike’s only real chassis flaw—unless you have short legs, and also find its height an issue—is braking. The conical front drum lives up to its poor reputation by refusing to lock the wheel even with the lever pulled back to the handlebar.

That lack of stopping power reinforced my impression of the Lightning as a limited but sound parallel-twin roadster whose preference for gentle cruising was in tune with its Californian-inspired styling. But that was evidently not the opinion of BSA’s management—at least, not for long. For 1972 the A65L was redesigned yet again, with lower bars, bigger fuel tank, more sober color schemes, and larger mudguards, as well as a revised frame and lower seat.

The new Lightning was more practical both at speed and in town, and most people who rode it thought it handled slightly better too. But if BSA had got the Lightning right at last, they were too late. By this time the famous old firm’s financial problems had deepened further, and production of the twins ended shortly afterwards.

1971 BSA A65L Lightning

Highs: Laid-back looks and easy handling

Lows: Feeble front brake, seat position if you’re short

Takeaway: It oozes ’70s style and parallel-twin charm

__

Price: Project, $3400; nice ride, $4400; showing off: $6000

Engine: Air-cooled pushrod parallel twin

Capacity: 654 cc

Maximum power: 51 hp @ 7000rpm

Weight: 419 pounds with fluids

Top speed: 110 mph

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Via Hagerty UK

The oil in the frame frame thing was an engineering blunder. This is why today the 1970 & earlier BSAs & Triumphs go for higher prices.

Really not a bad bike. It is a shame bsa could have done some simple fixes the first year, before they got out the door. I have one and it a great ride (after some fixes) .

1. Ditch the wobbly ft fender, some fork bracing is nice.

2. Dove grey frames? They were to be silver, but the paint was wrong.

3. Get a brake switch at the handlebar, not in the cable. Helps stopping with the conical (comical?) ft brake.

4. Shorter center stand, the one that came with it is impossible to put the bike up on it.

Frankly, I find the OIF chassis to be superior to its predecessors. That sewer pipe spine makes a rock solid connection between the headstock and swingarm. The swingarm itself, eh… The forks are remarkably competent providing you play around with oil viscosity and level. They need stronger tubes, but they far and away out performed the front end on my Suzuki GS 550 circa 1981. Ah, the brakes… Aftermarket brake actuating arms with increased distance between cable location and rotational axis for the lifters certainly improve things, but they cannot meet the capabilities of the prior year’s full width brakes. Were I a total fool with my money I’d figure out how to mount a Fontana front brake, but TBH the bike’s not worth it. As to the engine, if you are again a fool with your money, re-timing the crank to a 270 degree configuration, or balancing it properly, can make a world of difference. If you leave well enough alone and cruise around 4500-5000 RPM tops you will be pleased, above that crank speed you will suffer if you hold it for over a half hour. That said, a gentleman named Carl Donelson, and his wife, rode Lightnings from St. Louis to Florida and back with their children and no one complained. Carl owned a BSA dealership back in the day, and is a man’s man to whom I cannot compare. I can’t even stand up to his wife as she rode beside him. People were made of different stuff back then apparently… To close, I owned a Suzuki RG500 gamma tuned to the nines, chassis and engine, and a Lightning. If I really wanted to hoon around on tight country roads the Lightning was the weapon of choice, providing I shod it with Avon Road Riders. The gamma hit light speed on the straights but throwing it into a turn was a chore. The Lightning, with properly fettled forks and Hagon’s best shocks, allowed me to carry the same corner speed with more confidence until the peg scraped, which given that the pegs were solid mount, had me seeing jesus a time or two. The gamma pegs, being aftermarket rearsets, were also solid and when they scraped my butt was .5 seconds away from bouncing on the tarmac. I learned that lesson one time and the bodywork replacement cost really rubbed my nose in it.

Hi Scott

Any ideas on fork oil weight and amounts?

Nice looking bike, have a few BSA’s myself. Worked at a BSA/Greeves/HD dealer in the 60’s.