Media | Articles

Once “Cheap and Ugly,” the Subaru 360 is having an unexpected moment

Possibly the largest single-year valuation increase we will ever see for a classic car is for a … Subaru 360?

In the matter of just a year, the Subaru 360 has quadrupled in value. In January 2020, the value for an Excellent (#2) condition 1969 Subaru 360 Sedan was $10,100. Now, just a year later, that same microcar is worth $44,300. One look at the historical pricing on Hagerty Valuation Tools shows how dramatic of an increase we are witnessing.

A little over a year ago, in November 2019, a yellow 1970 Subaru 360 Deluxe in great condition sold on Bring a Trailer for a modest $8500, right between our #2 (Excellent) and #3 (Good) condition values at the time. Then, less than a year later, in October 2020, a 1969 Subaru 360 Deluxe in marginally better condition sold for $50,000 on the same platform. This second sale wasn’t an outlier, either: two other Subaru 360s sold for over $30,000 that same month at RM’s Elkhart auction.

Certain cars are famous for mobilizing the masses, and they are often especially beloved in their home countries. Germany has the Volkswagen Beetle, France the Citroen 2CV, Italy the Fiat 500, and in the United States, we have the Ford Model T. For Japan, it’s the Subaru 360—affectionately nicknamed the “Ladybug.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The 360 was Subaru’s first production car and Japan’s first mass-produced Kei car—a class formed specifically to provide inexpensive city cars for the working class. In 1955, Kei car engine displacement was capped at 360 cubic-centimeters, and just three years later Subaru dominated the class, selling nearly 400,000 examples between 1958 and 1971. Weight was kept low by means of a thin steel monocoque chassis and fiberglass roof, which helped make up for the meager 16 horsepower from the 360’s rear-mounted, 356cc two-stroke vertical-twin engine. The Subie also featured a four-corner independent torsion bar suspension, with finned brake drums bolted directly to the 10-inch steel wheels. Although it looks very basic, the 360 was fairly advanced for its time.

The 360 was a versatile platform offered in a variety of body styles, all conforming to Japanese Kei car regulations. The most popular of these variants was the two-door hardtop sedan (roll-back convertible top was optional), followed by a five-door “Sambar” van. For light utility purposes, a ramp-side truck was offered starting in 1961. Briefly, in Japan, Subaru offered a station wagon called the “Custom.”

For a hipper audience, Subaru made the “Young S,” which featured a slightly upgraded 25-horsepower engine, an extra transmission gear, bucket seats, tachometer, and a dented roof for a surfboard. An even “faster” version never offered in North America called the “Young SS” had all the modifications of the Young S with a dual-carb version of the 360 engine producing an impressive 36 horsepower. That’s 100 horsepower per liter! Watch out, Honda S2000!

The little Subie was underappreciated from the moment it arrived on American soil.

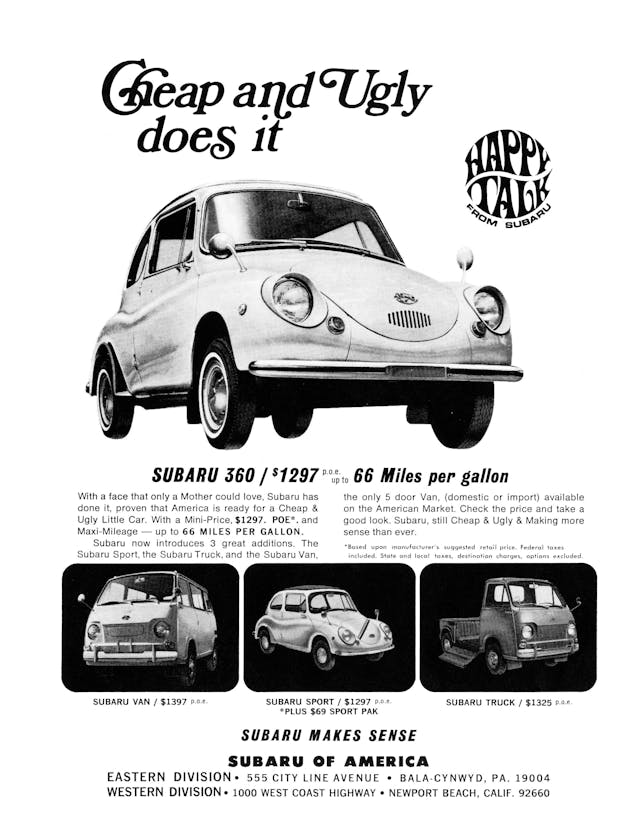

In 1968, Malcom Bricklin (of Yugo and SV-1 fame) and Harvey Lamm founded Subaru of America and imported 10,000 Subaru 360s to fill dealerships. The U.S.-market 360 was an improved version of the original sold a decade earlier in Japan. Engine output was increased to 25 horsepower and an overdrive fourth gear was added to the manual transmission, as with the Young S. An optional “Autoclutch” system eliminated the clutch pedal and operated the clutch automatically with an electromagnet. Gone were the days of pre-mixing oil using the fuel cap as a measuring cup, the new “Subarumatic” lubrication system mixed oil automatically from a reservoir in the engine compartment. Like the Model T, you could have any color you’d like—as long as it was white with a red interior. The Subaru 360 was advertised as “Cheap and Ugly,” with the $1297 price ($9850 in 2020 dollars) and 66 mpg as the main selling points. American’s didn’t care about fuel economy just yet, and the Ladybug flopped. Subaru’s roaring success these days all happened after a seriously rocky start.

In a period review, Consumer Reports saw the need for a small economy car in America but ultimately branded the 360 as “not acceptable” for American roads because of its poor safety standards and blatant lack of power. The publication claimed the car could not hit 60 mph on its test track, and it managed to clock a 37.5 second 0-50 mph time. For context, a 1968 Volkswagen Beetle could make the 0-50 sprint in 14.5 seconds. To give you muscle car fans a laugh, the CR testing crew managed to run the quarter mile in 28.5 seconds at 47 mph. You wouldn’t want to go much faster, anyway; the rear-hinged doors were known to fly open in high winds.

The brake system was the only thing worthy of praise, though the suspension setup caused the car to dive tremendously under light braking. “Just driving straight down an open road could be unsettling,” CR concluded.

On top of that, the 360 wasn’t as care-free as it appeared. According to the user manual, the break-in period suggests the driver never exceed 45 mph for the first 1200 miles and, although two-stroke motor oil was rarely available at gas stations, only one brand should be used for the life of the vehicle. In normal American driving conditions, the Subie only managed 25 to 35 mpg—nearly half what was advertised. The discrepancy is likely due to the car being designed for a Japanese city where speed limits rarely exceed 25 mph and average commutes are less than 10 miles.

More than anything, collision safety was a concern. Imagine a crash between this little Subaru and any 1970s American car. The driver of a Cadillac Coupe DeVille wouldn’t even notice. How did the 360 make it past American vehicle requirements in the first place? Due to a loophole, the sub-1000-pound curb weight made the 360 exempt from federalized safety standards. Bricklin, though, installed seatbelts to give some sense of safety. After its review, Consumer Reports suggested the National Highway Safety Bureau should remove the 1000-pound exemption from its safety standards.

Ultimately, a Volkswagen Beetle was only $400 more and superior in most respects. The American public agreed, and dealers were stuck with unsold 360s for years. Some even offered “buy one, get one free” deals to clear inventory. It’s rumored that unsold Subarus were loaded on a barge and pushed overboard to create an artificial reef off the California coast, but that probably didn’t happen. More than a few likely ended up being converted to go-karts at the hands of Bruce Meyers (of Meyers Manx fame) to be used at “FasTrack”, Bricklin’s next venture.

So, why the sudden Subie fever?

Modern Japanese classics are becoming a lot more valuable as of late, and in an age of nostalgia, collectors will look for deals in a marque’s earlier work. The 360 founded Subaru and is the company’s only car that many would consider “classic” (most legendary Subarus were made post-1980), so it likely strikes a chord with Subaru enthusiasts—a group that grows larger every year. The same thing is happening to early Hondas. The S600/S800 of the 1960s was Honda’s first production car sold in America, and it recently made the 2021 Hagerty Bull Market List.

Thanks to the passage of time, the flaws that made the Subaru a failure as a new car can now be appreciated as the early missteps of a nascent brand. When you look at other oddball microcars of the era, its amazing the Subaru 360 was ever priced under $10,000. An Excellent (#2) condition 1960 BMW Isetta 300 is $36,200. A 1964 Messerschmitt KR200 in similar condition is $53,600. Even at its current value of $44,300, the Subaru 360 seems like a steal compared to a 1963 Fiat 500 Jolly at $64,700.

Like the Jolly, maybe the yacht crowd is buying them up. The Subaru commercial below hints at that fact … maybe.

As a historically important vehicle, all of this attention tells us that the 360 is finally getting the warm welcome it hoped for, albeit 50 years too late.

Like this article? Check out Hagerty Insider, our website devoted to tracking trends in the collector vehicle market.