Media | Articles

This small shop produces some of the world’s greatest Volkswagen restorations

Wagenmasters’ Dustin Gomez never intended to shake the foundation of the Volkswagen community. Heck, he never even planned on moving into a shop space—or even putting a name on it. As he tells it, he just wanted to build the Beetle he never got the chance to finish back in high school.

“I daily drove a 1969 Beetle in high school. I loved it, but one thing had to go before college, and that was the car,” he recalls, smiling. “Fifteen years later, I would go to shows and leave thinking, ‘buy the car you never got to finish.” He found another ’69 and got to work, slowly restoring it in his driveway.

Seven years later, we’re chatting in the middle of Wagenmasters’ shop floor in Upland, California, sandwiched between a pair of 1956 “Ragtop” Beetles in two very different states of repair. To my left is a rusty, crusty Bug sitting sky-high on a lift, the undercarriage crossed with brittle twigs from a long hibernation in Oklahoma. The other Beetle is nothing more than a clean metal carcass awaiting primer.

Gomez tells me both cars are destined for Gooding & Company’s sales block at some point. In the years since that driveway restoration, Wagenmasters’ has become one of Goodings’ go-to sources for impossibly restored and impeccably presented air-cooled VWs. His restorations routinely command low six-figures on the block, with each sale inspiring several would-be buyers to place a similar build with Wagenmasters, never balking at the matching six-figure bill for a wheels-up project.

If you’re shocked at the prospect of a $100,000 Beetle, you aren’t alone. “The VW community has a love-hate relationship with us,” Gomez explains. “Because, if you’re trying to get into the serious restoration of VWs, you’re pushing the car into a market where it’s now hard to get.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

We first ran into Gomez at Gooding & Company’s auction preceding this year’s Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance. His 1959 Karmann-Ghia convertible was a standout at Gooding’s blue-turfed tent, attracting a mighty $123,200 winning bid that makes it the most expensive Karmann-Ghia ever sold at auction.

Whatever happened to das Volks wagen? What changed to make it acceptable to pay Porsche prices for old Beetles and Karmann-Ghias that were once the poster children for thrifty motoring? Gomez thinks it’s a combination of things. “Everything has been so crazy in the market for a while now,” he says. “And I think it’s our auction success that has further elevated the VW in collector’s eyes.”

A rising tide, and all that—but they made millions of VWs, and there are plenty of exceptional Volkswagen restoration shops around the world. I press him on what specifically is in Wagenmasters’ (WM) secret sauce. “I think it’s how we present it in a form of complete originality. And, the way we load up on the jewelry, the rare accessories, it elevates the car and gives it a humungous ‘wow’ factor,” he explains. “I think it’s something many collectors have never seen contextualized like that before. They know Volkswagen, but they don’t know it like that.”

He’s onto something there. Each Gooding-bound WM build arrives loaded to the valves with hard-to-find trimmings, some restored and some simply new-old-stock (NOS) parts dredged from every corner of the earth. We’re not just talking special shift-knobs or wheelcaps, either; Gomez tells us of dash-mounted coffee makers, map lights, radio upgrades, and window vents that have passed through his hands.

As these are simple bolt- or clip-on accessories manufactured in-period, each car could be considered “unmodified” — though it’s best not to approach a WM build under the impression these are numbers-matching, factory-sheet restorations. For the most part, each car is prepared with perfected period-correct paint, upholstery material/color, and options. So, think of WM’s creations as the idealized vision of that car.

In the shop office, he unlocks a glass display cabinet brimmed with enough rare goodies to outfit an ancient VW dealership. “This paper has to be at least 60 years old,” says Gomez as he pulls out a particularly rare a chrome wheel ring from its original brown wrapping. There’s a small dent in one of the lips. “I’m figuring out how to fix this,” he tells me. Unless he pointed it out, I probably wouldn’t have noticed—but those spending serious money on one of WM’s concours-grade builds sure would.

Then, there are the cars WM choses to restore. “[Official] Wagenmasters cars are all convertibles or ragtops,” Gomez explains, quite seriously. “There won’t be a coupe that goes to Gooding, as no matter what, it’s less money for a coupe. For us, the roof has to pull back.”

And, of all the multifarious Bug variants on the market, he tells me it’s the split-window, Ragtop Beetles—those with the retractable cloth roof section—with the optional “crotch cooler” side inlets that can be opened for fresh-air circulation that pry open the most wallets and snatch the most eyes. Amongst the “standard” mid-century Beetles, it’s the Ragtop that’s the standout model.

So, when WM brings a stunningly clean example of the “best” Bug wearing a crateful of desirable accoutrements to a tent filled with moneyed folks content with dropping seven- and eight-figure bank wires for a single car, tossing low-six-figures at one of the cleanest VWs in existence seems like a bygone conclusion.

“When our car lands at Gooding, it’s in a room full of one-million, two-million, five-million-dollar cars. What we bring is immaculate, but we’re still the cheapest kid in the room,” he laughs. “It makes it real easy to take us home.”

It also appears interest in top-shelf VWs is broadening. “I see people adding multiple VWs to their collection,” Gomez explains. “They start with a Beetle, then move into a Ghia, and then go into a Thing, and now they have a whole VW section in their garage.”

“It’s also a memory thing,” says WM mechanic Ron Lubetski. “They want something to remind them of their youth.” Gomez nods: “They’re thrifty, and they’re conversation pieces. Wherever you go, people want to stop and talk about it. Someone, somewhere, somehow had a Bug in their house.

That enthusiasm appears to be contagious. With each WM car sold, the market price goes up and his phone rings off the hook with would-be bidders looking to restore their dream VW or simply recreate the car they couldn’t buy at Gooding. It’s great for business, but restoring VWs is no longer the cheap-‘n-cheerful process it used to be. Quality parts availability is becoming a real concern, and as people notice the sale prices spiking, they’re hoarding original body panels and the like. “I just paid $700 for one fender. Before, when I started doing this, I could grab a fender for $50,” Gomez sighs. “Now everyone knows the value behind an Oval,” referring to 1953-1957 cars with oval rear windows. Regionality is also a hurdle; the WM team sources old VWs from everywhere except California, where VW culture is strongest and good cars are significantly more expensive than out-of-state.

Realistically, a restoration of this quality and detail was always going to be expensive, VW or not. Metalwork takes time, as does sweating the small stuff—an often-obsessive activity that’s not considered a pejorative in the concours world. Gomez tells me of the struggles surrounding the Karmann resuscitation, and how he had to “cut the car in half” at one point in the process.

I ask Gomez and Lubetski what’s next for the VW market. “I think it’s going planetary in the next year, year-and-a-half if the economy stays as it is,” says Gomez. “Like $20,000 for a rolling chassis. I think a car like this [ragtop] will be a $150,000 car after it leaves our hands.” There has to be a plateau point, right? “I’d say $150,000 to $175,000 for the best cars,” Lubetski says.

Again, this kind of cash was never part of Gomez’ plan. That 1969 Bug was just a fun project to scratch the itch. After a summer of daily cruising, he sold the ’69 for solid profit at a Mecum sale in Las Vegas, using the unexpected windfall to source a 1957 Volkswagen “Ragtop” Beetle from an older enthusiast in his hometown of San Dimas, California. Another driveway restoration ensued with the help of neighbors, friends, and family.

That ragtop proved pivotal in the WM story, reverently referred to by Gomez as the “Coral car,” so-named after the finished project’s pastel Coral Red paint. As he tells it, this was also the start of WM’ recognition as one of the leading sources of rare accessories, as the Coral car was quite the canvas for Gomez’ collection; aside from a charming paint-matched Allstate single-wheel trailer, the car wore hard-to-find extras like cross-laced beauty wheel rings, Petri Pelite steering wheel, NOS fender skirts, and a Hella searchlight, among others.

It was more presentation than car. “I noticed that regardless if it was a VW-specific or American show, the Coral car would sweep the awards. I was beating Chevelles, Mustangs, Bel-Aires,” he says, still sounding surprised.

The car’s shocking $61,600 sale at Barrett-Jackson’s 2018 Scottsdale extravaganza woke him up. “That lit a fire inside me — now I had to find every oval window out there,” he laughs. “But, when the Coral car sold, everything changed. I [originally] bought the car for $5,000, and after it sold, everyone was asking like $14,000 [for cars he would inquire about buying], saying ‘We know what you can do with the car.’”

He quickly sourced another 1957 ragtop, this time from New Mexico, followed by the 1959 Karmann-Ghia Convertible project from the same San Dimas enthusiast who sold him the first ’57. Meanwhile, people started to take serious interest in Gomez’ driveway builds. “People started knocking on my door, asking if I’d build a car for them. At first, I turned it down because I was too deep in my own projects,” he explains. “In the beginning, it was just me and friends I could find and offer a few bucks to help me wrench. I didn’t want to paint myself into a corner.”

Family and community is a common theme at WM. Gomez’ girlfriend is the shop manager, and his mother does the books as part of her existing bookkeeping business, with mechanic Ron Lubetski and his son Hunter making up the remaining half of the four-person team.

Even the name “Wagenmasters” holds deep roots in Gomez’ community. Admittedly self-taught primarily through books and videos, Gomez volunteered at the local VW workshop in high school, serving as the shop grunt who cleaned and moved parts around. “I was looking for anything I could to push my first Bug over the line,” he remembers with a smile. The shop unfortunately closed just a few months after he started, but his time there made a lasting impact.

When it came time to make his own work official, Gomez could think of no better name than the continuation of the old defunct shop of his youth, only with one key difference—Wagenmasters in place of the bygone Wagonmasters.

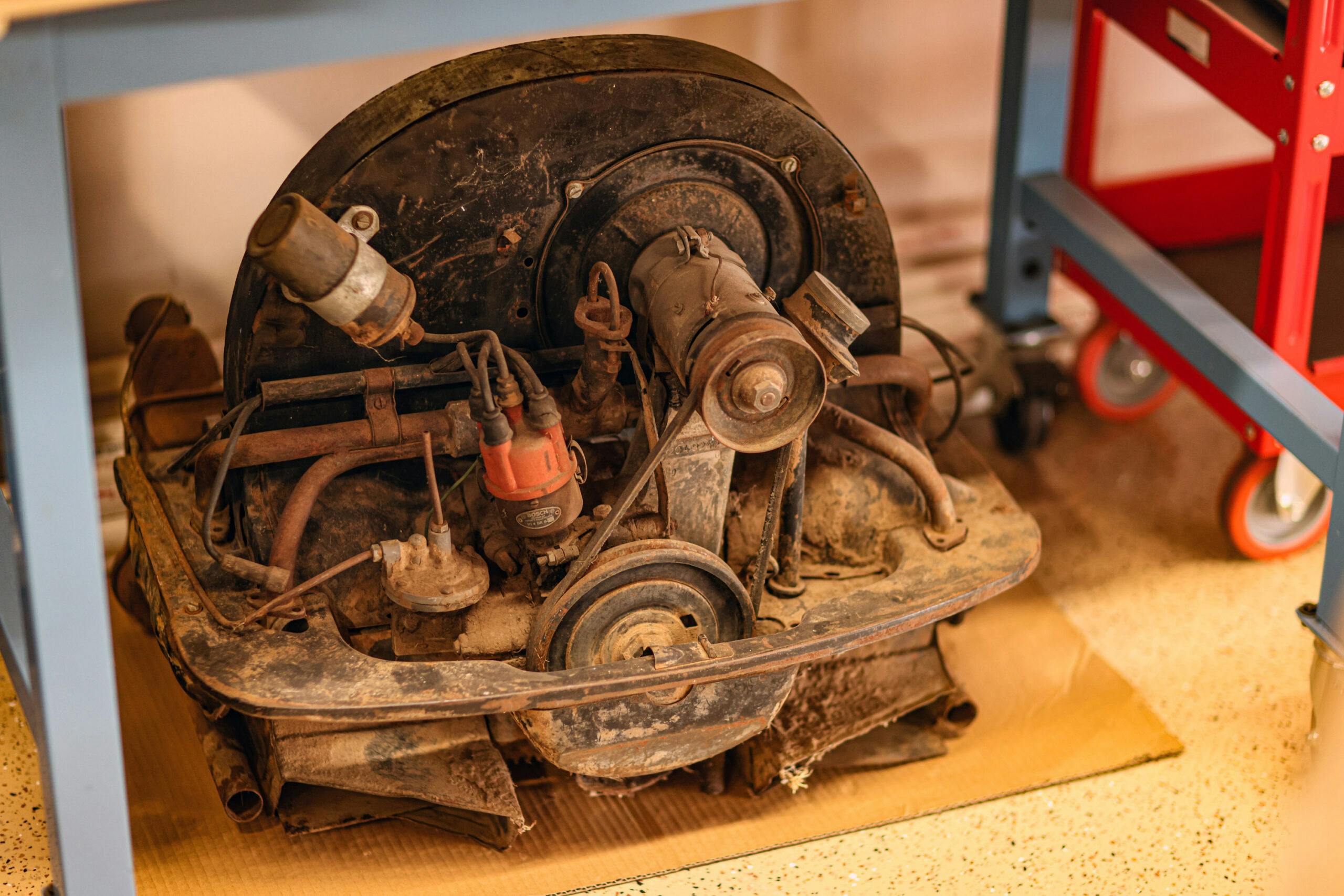

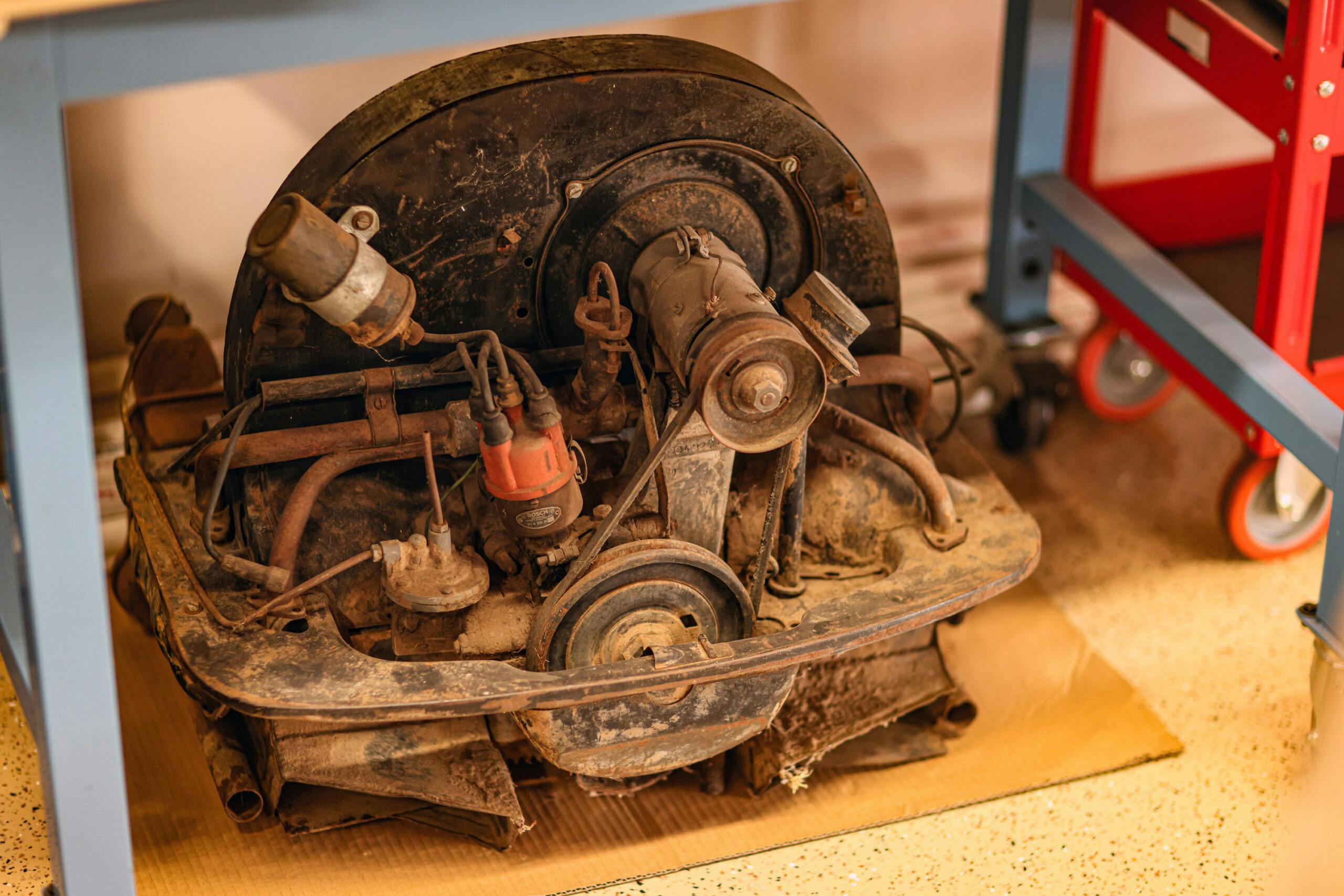

Now, WM is busier than ever. At the time of my visit, WM had three cars in various states of restoration slated for Gooding sales, with four or five customer cars in line for restoration—which now is a year-and-a-half turnaround process. Even so, don’t think you have to spend $90,000 on a rusty ragtop to get shop-space with the WM team; despite the record setting sale and a portfolio of award-winning wheels-up restorations, WM happily offers standard servicing to anything with a VW pancake motor.

WM is surprisingly upfront with hourly rates and service pricing on their website. “It’s what I wanted when I was working on my own car,” says Gomez. And, since they’re not entirely removed from their Volkswagen cousins, WM is also open to restoration and service on Porsches. As everything aside from paint and upholstery stitching is done in-house, they won’t touch something hyper-complex like a Carrera four-cam, but anything with a standard 356 engine is welcome—as proven by the shop’s gleaming, freshly restored drop-top 356 just waiting for finishing touches.

I ask Gomez what he sees in the future for Wagenmasters. “This, and hopefully the bay next door,” he says, gesturing at the small two-car workshop. “No bigger. We all love what we do here, and then we go home and eat dinner. In the long run, we’re all home on time.”

“It’s all I’ve ever wanted to do – build cool cars and make it home for dinner.”

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Via Insider

Deja Vu article. Like the blue interiors/exteriors.

“Most houses had a VW in them.” Likewise, my parents had a ’66 Pontiac Executive . . . a long, long car. On the day I took my test for my driver’s license, I opted for my brother’s ’63 Bug. Much easier to parallel park!

I aced the written test but backed my Dad’s ’62 Beetle over the curb when I parallel parked. My best friend never opened the manual to study for the written test, but parallel parked his Mom’s ’64 Buick Electra 225 easily. I nailed it when I retook the DL test, but he never let me forget my first attempt.

I LOVED THE OLD BUGS EXCEPT FOR HAVING TO ADJUST THE VALVES EVERY 5,000 MILES

Just guessing nere, but our 79 Super Beetle is probably one of the cheapest bugs out there, because of the fuel injected engine. Nobody in California wants one because it’s not old enough to get around the smog requirements, and the FI parts are pretty much unobtanium.

It’s still a blast to drive, and it gets lots of looks on the road.

It sounds like Wagenmaster is too laid back to be a TV series.