Media | Articles

The end of the cheap Miata is near

When Vivian Topaz was 14, she told her father she wanted a Miata. He immediately vetoed the idea.

“He said, ‘You’re not getting a Miata. It’s a hairdresser’s car,’” she recalls. “I said, ‘No! It’s the cutest car ever.’ I found one in Ojai on a dirt lot. The guy wanted $700 for it. I’m like, ‘Oh, my god! Dad, we have to get that car!’”

The 1995 Miata had “horrible” paint, a failing water pump, and an improperly timed ignition. But Topaz and her father were able to drive it home. Three years later, she’s put 20,000 miles on the car, which now features a roll cage, new body panels, an upgraded suspension and bigger wheels and tires.

“The Miata is the perfect first car,” she says. “It’s cheap, there are so many aftermarket applications for it, and I can work on it by myself.” Topaz, a certified welder, has only one complaint about the Miata. “Prices are going crazy,” she says. “You used to be able to get cars for 500 or 600 bucks. Now they’re $1500 or two grand.”

Granted, $2000 still sounds like an epic bargain, especially if you normally haunt Bring a Trailer auctions. But Miata prices are skyrocketing just as quickly as you move up the food chain. During the past year, for example, the value of a condition #2 (Excellent) 1992 Miata has risen from a tick under $15,500 to $18,300.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Of course, the Miata isn’t a complete outlier in the collectible-car world. The prices of Japanese sports cars in general have zoomed ever upward as the love affair with “youngtimer” models continues to flourish. But the Miata isn’t riding this wave so much as it’s helping propel it. Prices of 1990–97 Miatas have climbed by 130 percent during the past five years, according to Hagerty data—that’s nearly twice the national average.

Cars become collectible for a variety of reasons. Scarcity, cachet, looks, performance, nostalgia, perversity, whatever. In the case of the Miata, the most important reason for its success is its fundamental goodness.

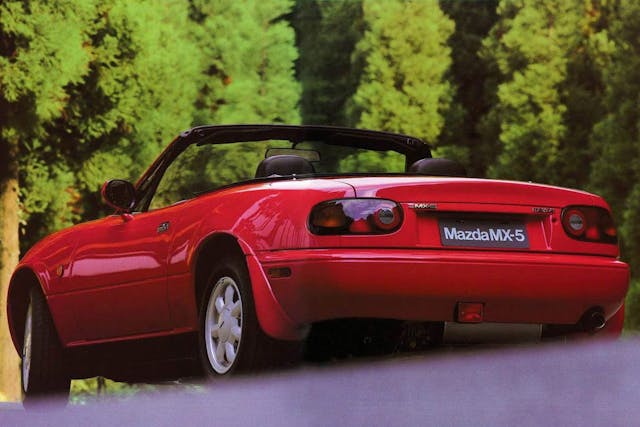

Introduced in 1989 as a 1990 model, the MX-5—as the car is sold elsewhere in the world—married the pluck and open-air panache of British roadsters with the build-quality and indestructibility of Japanese family sedans. It was an immediate hit with both car-buying consumers and car-reviewing journalists, and it’s never fallen out of favor. “Miata is always the answer” is such a long-running cliché that it’s become a post-ironic meme.

Although the Miata has gone through four iterations over the past 32 years, most people associate the nameplate with the original car, a cute-as-a-bug ragtop with flip-up headlights known internally as the NA. The second-generation NB (1999-2005) and third-gen NC (2006-15) moved progressively further away from the purity of the NA. The current ND, which debuted in 2016, makes a good-faith effort to return to the jinba ittai– horse and rider—concept baked into the first Miata. But the NA remains sui generis, a unicorn that defies replication.

Even as the world has changed, the first-gen MX-5 never went out of style. And it’s now finding a new audience with young buyers who see the car as an exemplar of an automotive world they were born too late to enjoy. According to Hagerty’s research, members of the Gen-X cohort (born between 1965 and 1981) don’t have much interest in Miatas, period, maybe because they grew up with them, and familiarity breeds contempt. But millennials and Gen-Zers have a yen for the NA.

Larry Oka, who owns one of the largest and longest-running race-car rental businesses on the West Coast, focuses on first-gen Miatas and nothing but first-gen Miatas. Since he’s always looking for cars to transform into Spec Miata race cars or freshen up for resale, he keeps a close eye on the market, and he’s got a theory about why prices are climbing so inexorably.

“The high school kids are snatching them up because they’re fun cars with a stick shift. They’re also entry-level, and they’re fully depreciated,” he says. “They want something with an airbag for their parents, that gets 30 miles per gallon on regular gas and that’s easy to work on in their driveway.” In other words, an NA.

Generally speaking, younger buyers don’t have a lot of money to spend, which means they often start with beaters that they use as daily drivers. The idea of returning a car to stock form seems to be an alien notion to owners who’d rather invest in modifications that make their cars faster or lower or more comfortable.

Jack Heideman, a 25-year-old engineer, bought a ’91 for $1100 six years ago. “I was looking to get a cheap car to autocross,” he says. “My goal was to find a Miata for a thousand bucks. The alignment bolts were rusted solid into the bushings, so it turned into a nightmare.” Although Heideman modded the car extensively, he returned it to stock form before selling it last year. Most owners aren’t so fastidious. “Most of the cars I see now are hacked,” he says.

But NAs don’t appeal only to young consumers on tight budgets. Hagerty data also shows that they’re also popular with boomers and so-called pre-boomers. Older and with more disposable income, these buyers are willing to pay a premium for nicer cars that embody the qualities that made the Miata an instant classic when it debuted.

John Linney owned a right-hand drive MX-5—which he thought of as a bulletproof Lotus Elan—while he was living in the United Kingdom in the 1990s. Now 62 and settled in California, he recently bought a 1991 model with 31,000 miles from the original owner.

“It’s a perfectly balanced car,” he says. “It seems to run out of traction at the same time it runs out of power. But the lack of power is an attribute rather than a bug. The Miata is a car you can drive on the limit on public roads without risking life and limb. It’s more fun to drive a slow car fast than a fast car slow.”

Another selling point of the NA is dependability. Yes, most Miata projects can be tackled by a modestly accomplished shade-tree mechanic. But unless the car has been hot-rodded injudiciously or run into the ground, it shouldn’t require much in the way of DIY wrenching.

“I’ve driven three NAs over the Alcan Highway to Alaska from Raleigh, Kansas City and Sacramento, says Kevin Kastner, director of marketing and sales at Moss Motors, a major Miata aftermarket parts supplier. “There is no car that offers nearly as much fun, simplicity, and reliability.”

Fun, simplicity and reliability will always be part of the Miata recipe, but in terms of affordability, things are shifting. Alas, the days of first-gen bargains are receding in the rear-view mirror. Even on Craigslist and Facebook Marketplace, it’s rare to see anything under $2500, and most cars slot in between $5000 and $10,000. (The average condition #3, or "Good" condition value for an NA in the Hagerty Price Guide is $9400.) But what’s really stunning, at least to people who’ve following watching this segment for a while, is the proliferation of high-end sales. The average condition #1 (Concours) value in the Hagerty Price Guide for an NA is a whopping $31,900.

“We have seen an increase in ‘restoration-style’ products for the NA,” says Keith Tanner, director of e-commerce and systems at Flyin' Miata, another big aftermarket parts company. “Still lots of pure performance stuff—people are more willing to pay $2000 for a suspension today than they were 20 years ago—but people are putting the money into them to fix them up instead of leaving them ratty.”

Which begs the question: Can prices keep rising, or has the spike been the product of the lockdown, social-media enthusiasm or what economists call irrational exuberance? It’s odd to think about a car built in such large numbers—more than 400,000 units from 1989 to 1997—graduating to collectible status. Then again, who doesn’t like the Miata? Even as automobiles powered by internal-combustion engines are being increasingly demonized, the spunky Japanese two-seater still has the power to put smiles on people’s faces. And you know what they say:

Miata is always the answer.