Media | Articles

Restored vs. Preserved: 2 Distinct Daytonas Yield a Similar Outcome

For decades, the concept of complete restoration has been considered the ideal form for the best cars in the collector car hobby. The notion of preserving cars—keeping them as original as possible, or in their in-period as-used state—may have been pioneered by the likes of Briggs Cunningham in the mid-twentieth century, but it really only gained traction within the last 25 years. Preservation classes are now welcome on the concours lawn, but for the most part restored vehicles still command the most value. There are, of course, exceptions to the rule: Two strong sales of Ferrari Daytona Spiders at the Amelia auctions uncover a scenario in which preservation ruled the day.

Before diving into the subject cars, some context: the Daytona has long been a mainstay of the Ferrari collector market. As the last two-seat front-engine V-12 car till the 550 Maranello’s 1996 debut more than 30 years later, the Daytona was the ultimate iteration of Maranello’s brawny, traditional-layout GT car. It also stood at a pivot point for the brand, using the classic long hood, short deck sports car architecture Ferrari road cars were known for up to that point while also stepping toward the angular, fresh design cues of the budding supercar ’70s. As a result, the Daytona sold well when new and was quickly welcomed as a collector car when the Ferrari boom gathered steam in the late ’80s.

Correspondingly, the market put a premium on Daytonas, particularly the 121 factory-built Spiders. Later models tend to be more prized, and at $2.35M for a #2 (Excellent) condition 1973 example, the Spider is about 3.5 times as valuable as its tin-topped sibling (in large part due to the high count of coupes made—1284, which was a lot for a Ferrari of the era). Prices for both have retreated slightly in the last few years, but the rarity of factory Spiders has helped maintain their status among Ferrari collectors.

While Daytonas of any kind aren’t auction stage regulars, Spiders naturally show up less frequently than coupes. This year’s Amelia auctions were graced with two. Broad Arrow featured a meticulously restored, well-optioned 1973 example, while Gooding brought a supremely-preserved 1972 car that, aside from a 2015 repaint in its ultra-rare original Verde Bahram hue, was incredibly original and showed just 7827 miles. Both sales were strong, each handily exceeding the $3M mark—well above the #1 condition Hagerty Price Guide values for each, to say nothing of their condition-appropriate values. But the preserved ’72 nabbed 10 percent more—about $330,000—when all was said and done.

It’s certainly not for anything lacking on the part of the restored car, Broad Arrow’s 1973 Daytona, which sold for $3,305,000 including fees (about $1M over its #2 condition-appropriate Hagerty Price Guide value). Completed in 2018 and wearing a respray of its original shade of Blu Dino Metallic paint and a completely new interior, the car received a thorough mechanical and cosmetic renewal.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

It ticks the boxes that collectors look for, too—the car is Ferrari Classiche certified, features sought-after options like a Becker Mexico stereo, and retains its manuals and tool kit. Post-restoration hardware includes a Best in Show at the 2018 Concorso Ferrari in Palm Beach, Florida, and an Amelia Award in the Scaglietti Production Class in 2020. According to our analysts, aside from very minor details like slight fogging on the gauge lenses and hints of use on the interior (use is never a bad thing, of course, but any wear is noted when our team grades a car’s condition), this Daytona was a near-poster-child pristine example of a recently restored car.

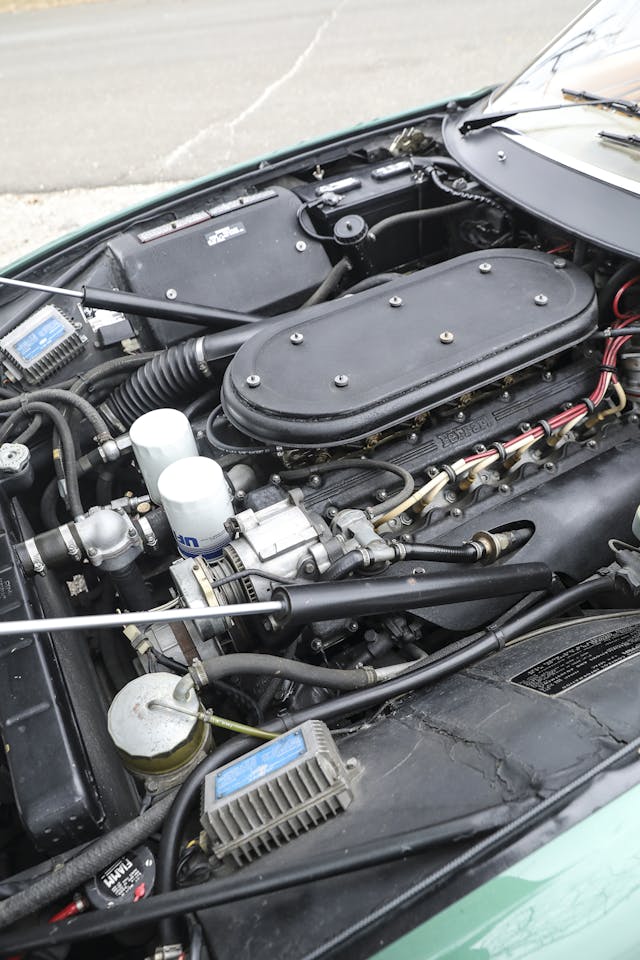

Gooding’s ’72 Daytona might not have had the restorative attention received by the Broad Arrow car, but its appeal lies in that it’s not only one of the very few near-original Spiders that remain, it’s in very good condition to boot. Our analysts rated it as a #3 (Good) condition car, noting that it appeared as a quality example showing some age. The sole update, a 2015 repaint to its original green from a previous black respray, had some minor spidering on the hood, the bumpers showed slight scratches and pitting, and the engine bay needed a thorough cleaning. Inside, the original seats and dash are in remarkably solid shape, which may be attributable to the car’s low mileage. Daytona seats were notorious for early wear, with many having been reupholstered by the early ’80s.

Gooding noted that the car was one of just five Daytona Spiders finished in green, and suggested that it might be the only Verde Bahram metallic-over-beige Spider to ever leave the factory. This striking combination along with its condition and originality sent bids sky high, and it sold for $3,635,000 including fees, just short of the Daytona Spider record of $3.72M set in 2014.

In this circumstance, rarity is the primary factor that helped blunt the edge that restoration typically has over preservation, and its impact is twofold. First, scant few Daytonas exist to begin with, but combine that with a unique and desirable color combination that takes a car from one of 121 to potentially one of a few, and a car’s level of restoration becomes less significant in the overall consideration of its value. That’s especially true when “preserved” isn’t just a marketing word for “in tatters” and the case in point is in very attractive, usable condition like this one.

Second, you can’t re-preserve a car, and with time, fewer such examples exist as they are either restored or succumb to age and the elements. In this instance, there are so few Daytona Spiders in this near-original condition that the fact it has been repainted in its original seldom-seen color was not a mark against it. The increasing rarity of preservation examples among any given data set, whether Daytona Spider, long-hood 911, Corvette, or otherwise has itself become a valued attribute.

Ultimately, these two sales demonstrated that the market accepts more than one path to achieving top-flight value.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

What?

A respray to correct a previous respray is a restoration. Body-off, every nut and bolt no… but still a restoration.

It’s even stretching the definition of “preserved” once you get under 50% original body paint (I’ll concede rusted rockers, a hood, quarter panel from a fender-bender, etc. having needed a respray).*

“Original” it better be the original paint, crinkled hood, rusty rocker and so on (though preferably just pristine –mint original, worn original vs. beat original if you will).

*”preserved” is a little different if you are talking about a race car or custom. It also becomes a great question of whether to restore or not. The Hirohata Mercury could have been preserved when Jim McNeil brought it back into the public eye –but that would have been in a colour scheme most didn’t remember with a primer fender, and other flaws. The story of it’s restoration refueled the legend, and the recent big sale of that car clearly says restored was the right choice.

https://www.hagerty.com/media/car-profiles/the-extraordinary-effort-to-restore-the-legendary-hirohata-mercury/

If a race car exists in the correct livery (drag cars and salt racers were notoriously passed down and altered beyond recognition for example) the better investment might be to preserve it derelict/as found. Sometimes they are cooler as found (I get that many Ferrari restorations back to original is worth more than ratty race car –at the show you’ll find me staring at the ratty race car).

Can’t argue with that.

It’s a beautiful car regardless. Obviously with a limited amount of cars that’s going to affect the cars value upward. The reality this is a car that only a few can buy and I do wonder if they care since it’s well done.

It really is a pick your poison isn’t it? Who’s to say that from one week to the next the whether the fully restored or original will be sold for more. And where do you draw the line at the distinction between the two? If a car doesn’t have the original paint but was brought back to the factory color was it restored or ? You can reduce that argument to the absurd and say it no longer has it’s original wiper blades, this fuse was replaced, it hasn’t got it’s original oil. Do you really want to have an old wet cell battery? I’ve done a considerable amount of restoration work of old elaborate buildings , plaster work is a dying art. More than once I’ve heard the board members say – ‘ We want to bring it back to as original’ – only to find out that the original colors were, while then the style, garish. I presented two panels. One ,the as original, powder blue and white with gold leaf. The second a more toned down earthy colored version, like we’re accustomed to seeing in old architectural landmarks from early Greece and Roman which is NOT how they were originally finished. ( more Viva Las Vegas in reality ) . After the board and the historical society hemmed and hawed they finally asked me – ” What do you think?”. I decided to be less than polite, pointed to the original paint scheme and said – “This one looks like a French whore house” .The second was then unanimously chosen. Pick your poison.

What’s wrong with a French whorehouse?!

Daniel _ To answer your question, as my father frequently said – “It’s a nice place to visit but I wouldn’t want to live there.”

It sounds like 99%+ of the Gooding Daytona is original. If that’s not good enough to get you in the Preservation Class door, then maybe – as one comment mentioned above – all subjectivity should be removed from the equation and entrants to the class required to be in their 100% as-delivered -from-the-factory condition.

Or, we could just continue to let reasonable people make reasonable decisions.

At the other end of the spectrum, Mr. Eckart said (paraphrasing) ‘“preserved” is sometimes just marketing speak for “in tatters”’, which I think is more of a problem than the worry about over-restored cars being entered in the Preservation Class. I have a difficult time understanding the value in exhibiting a vehicle whose sole reason for being is to display just how decrepit it can become before finding its final resting place at the crusher.