Media | Articles

How “numbers-matching” came to matter for collector cars

Numbers matching” might be the broadest umbrella term in the collector car industry. At its core, the term is intended to convey the idea that the major elements of a car—chassis, body, engine, and drivetrain—are the ones that were on the car when it left the factory. In truth, though, “numbers matching” means very different things across different manufacturers and time periods. This has opened the door to a looser application of the phrase, and more than one instance where an ambitious seller’s definition may not be the same as a hopeful buyer’s.

Understanding even a brief history of what car companies tracked—and what they didn’t—along with knowing how the methodology of serializing parts evolved over time enables potential buyers and casual observers to get a better read on the car that sits before them and the claims being made about it.

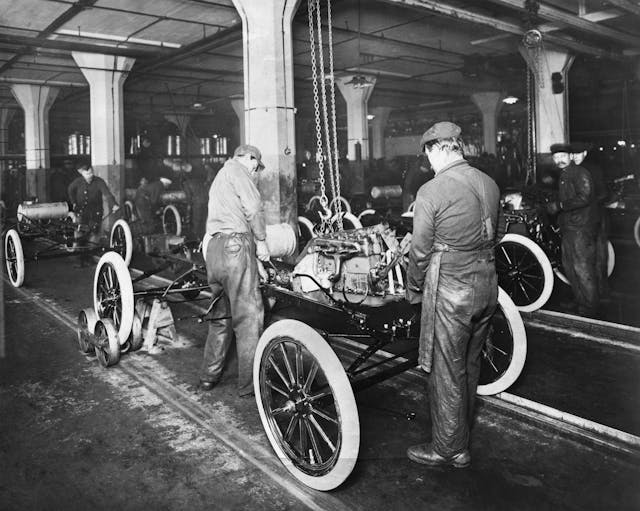

Collectors were not always obsessed over complete originality. They didn’t have to be. At the dawn of the automobile, there were sequential numbers only on engines, the component that defined an “automobile.” Sequential numbers for chassis didn’t exist. Even after the turn of the 20th century, when specific chassis and body numbers began to be used, they were of little consequence.

Henry Ford’s definitive Model T is identified only by its engine number. He didn’t care if this or that sequentially numbered 20-hp, 177-cubic-inch four-cylinder was dropped between the frame rails. He cared that the four-cylinder was just like all the other Model T engines, produced in quantity and dropped into a Model T frame at the moment when the two happened to meet up, completely by chance, on his assembly lines.

“Matching” numbers didn’t exist, nor did they matter. In the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s, even great cars like Duesenbergs regularly had their major components swapped around to keep them running. If it looked and ran like a Duesenberg, even if the engine, transmission, and rear axle left Duesenberg’s factory attached to different chassis, it was still a Duesenberg. The same was true of Packards, Lincolns, Pierce-Arrows, and their counterparts.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

This all changed after 1954, at the drop of the green flag on the great horsepower races, when different drivetrains began to be available in the same make and model. No longer were six or eight cylinders and a standard or automatic transmission the only options. By 1957, for instance, Chevrolet offered four different 283-cubic-inch V-8s—just in Corvettes. They could be had in big Chevys, too, along with the more common 162-hp, 265-cubic-inch V-8; the entry-level two-barrel 283 with 185 hp; and the two -barrel “Power Pack” 283 with 220 hp. Ford had five different V-8s. Plymouth had four.

Almost instantly, but certainly with the passage of time, the concept of the car as it left the factory—body, chassis, engine, transmission, rear axle—carried more weight. As years went on, engine swaps for performance or simply to keep a car running became more common. Since value is so often determined by configuration and equipment, originality started to matter.

An F-code 1957 Thunderbird’s purity became an important distinguishing feature, and one with its original 312/300-hp supercharged V-8 was more pure and worth more than another F-code T-bird with a junkyard-salvaged D-code 4-barrel Thunderbird Special built up to F-code specs. The problem was how to determine what was original and what was replaced.

In most respects, the core component of a car’s performance, and its rarity, is its engine, and engines were manufactured in a different factory from the one in which the car was assembled. For convenience (and accountability), engines get numbers when they’re put together. These numbers are not sequential, however—instead they’re generally a combination of a factory code, a date, and a letter-number sequence that identifies the original configuration—a 290-hp 318 with dual quads with an automatic transmission, for example. Shipped to a vehicle assembly plant, each engine was integrated into the plant’s production schedule to be installed in its intended car.

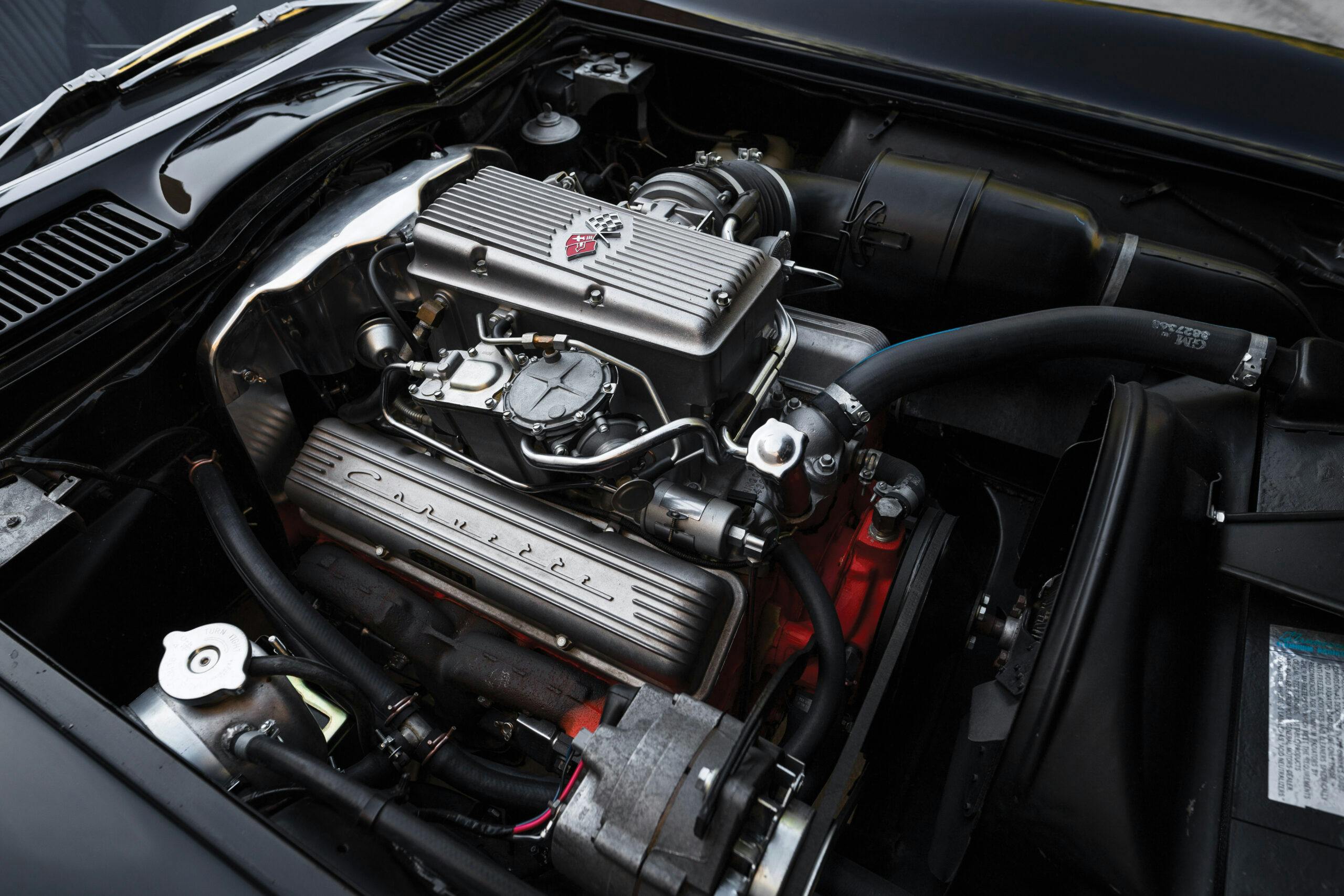

There were still no “matching numbers” on the engine, but in 1960 Chevrolet acknowledged the importance of accurate configuration and began to stamp a derivative of the intended chassis number on the engine itself, creating the definitive concept and origin of the term.

Take, for example, a 1963 fuel-injected Corvette coupe at RM Sotheby’s 2020 auction in Arizona, with its engine pad stamped 3106704 F1016RF. It translates to the Flint engine factory, October 16, 327/360-hp, and a manual transmission, for 1963 chassis sequential number 310670. This was all correct for the car as presented and definitively “matching numbers.” It helps that the October engine build is consistent with the Corvette’s chassis number sequence, 6704, appropriate with its place along the ’63 Corvette numbers continuum that ends at 121503.

The trouble is that beyond Chevrolet, no other domestic carmakers go to this detail. Not Pontiac, Oldsmobile, Buick or Cadillac. Not Ford. Not Chrysler. Claiming “matching numbers” anywhere else takes a different and more subjective analysis, almost always relying on the terms “period correct” or “date-code correct,” unless the ownership history is short and completely identified.

There are many individually stamped and identified engine numbers across all U.S. manufacturers, but they are internal accounting numbers. Useful mainly to production planners, they convey little intelligence about the car in which they eventually ended up. Instead, numbers must be inferred—a process that is pretty simple, if not entirely reliable.

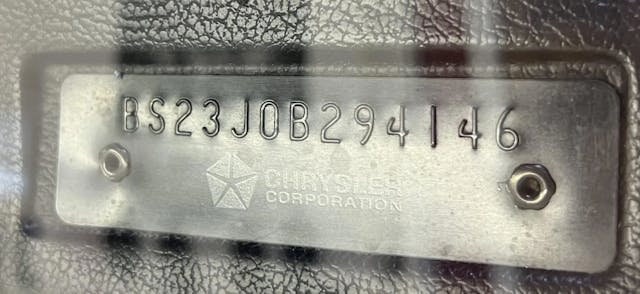

For Fords and Mopars, we know what the original engine configuration was; it’s encoded in the chassis number or Vehicle Identification Number (VIN). A ’70 Cuda T/A will have a “J” in the fifth position signifying the 340/290-hp six-barrel (Six Pack in a Dodge Challenger) engine configuration. A ’70 Mustang Boss 302 will have a “G” in the fifth position for the 302/290-hp V-8. Those codes should coincide with what’s under the hood. From there, it gets more circumstantial.

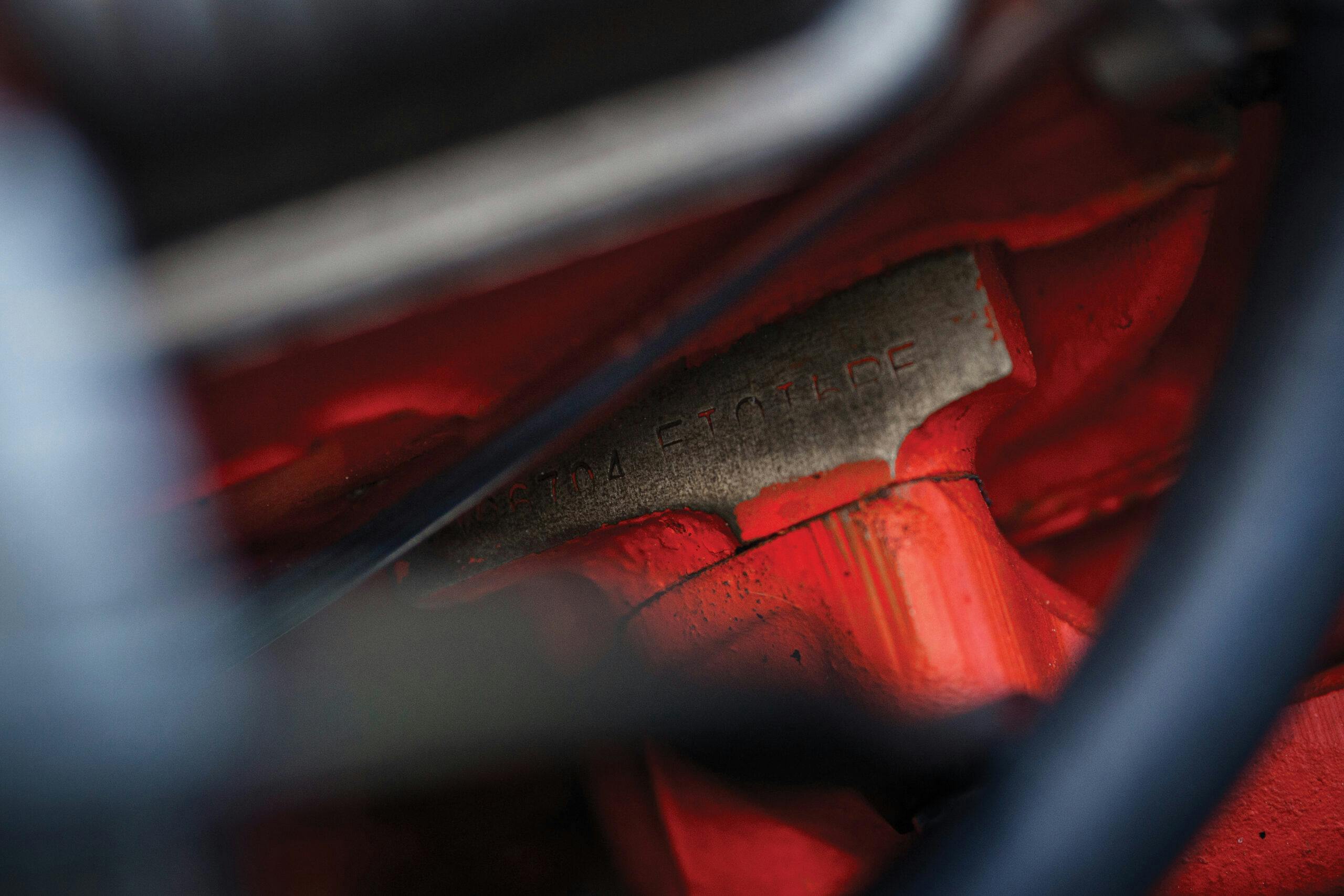

Each casting (cylinder block, heads, transmission case, etc.) has a part number cast into it, making it largely immutable. Each casting also will have a casting date, usually a circle with the month and day indicated. Engine components are cast and engines are machined and assembled at only a few places, then shipped to vehicle assembly plants scattered across the country. Casting dates must come before the assembly date for the engine, which itself has to come before the chassis assembly date to allow time for shipping and scheduling.

By deciphering the casting part numbers and dates, the origins of each engine and its intended configuration are discoverable. There are experts who know such detail intimately, but also there are also reference materials that reward research into specific cars and drivetrains. Also valuable: crawling under the car with a flashlight.

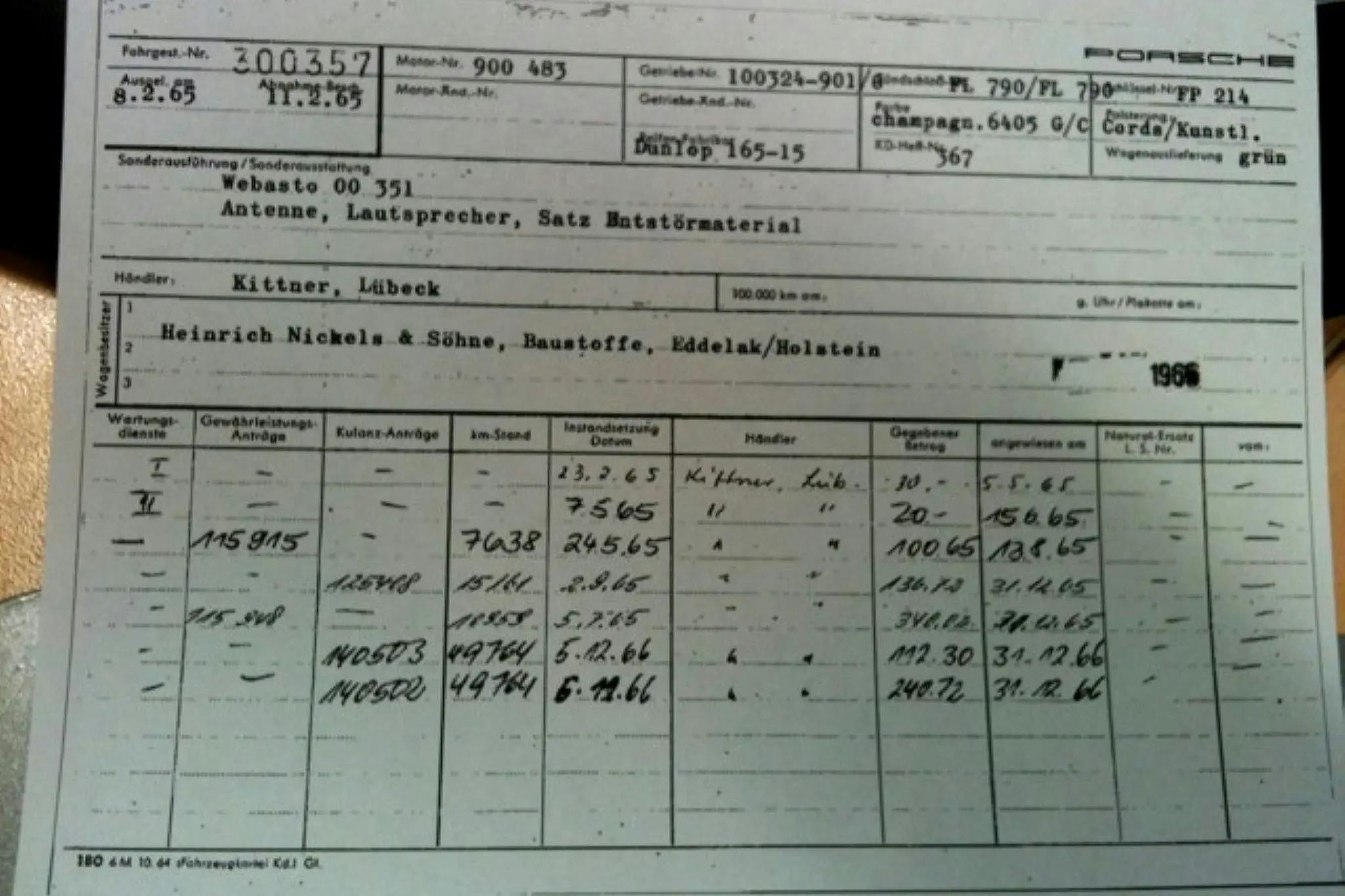

Matching-numbers verification for low-production European cars like Ferraris, Porsches, and Jaguars is more straightforward. Build sheets and the famed Porsche Kardex recorded the engine number detail as the car left the factory. Even without access to a Kardex, the engine number ranges for Porsches are widely available. An early ’57 Porsche 356A 1300 had a 44-hp engine number between 22472 and 22999; later in ’57, the 60-hp 1600 was between 67001 and 68216, with the chassis numbers similarly defined for coupes, cabriolets, and Speedsters. Engine numbers that fall outside that range would not be “matching.” Jaguars have two engine numbers: one on the cylinder head and another on the block, just above the oil-filter housing. Those numbers should match and correspond to the original chassis tag as well as to a Jaguar-Daimler Historic Trust Certificate.

Outside sources can be a help. Kevin Marti has established the Marti Report as the definitive description of any Ford product’s original configuration for the years 1967 and later. Pontiac Historic Services (phs-online.com) has salvaged similar Pontiac records for 1961–1999, and, bless their hearts, the people at GM Canada have preserved production records for cars built north of the border.

None of these sources, however, reference engine numbers, which makes them of limited use—except in the most generalized terms—in defining actual “matching numbers.” Instead, they support the concept of “matching numbers” stated earlier as imprecise shorthand for a car that has its major components as it emerged from its original assembly plant decades ago.

In any “he says, she says” situation, there is rarely certainty. Cars for sale are often their owner’s prized possession, acquired at great cost, meticulously restored, and obsessively maintained. An owner’s stature and self-image are reflected in the car, and searching for numbers may be perceived as casting aspersions on the veracity of an owner who represents it as matching numbers.

The numbers themselves may be hidden under closed doors and hoods; it’s always best to ask before touching, and even then, further inspection may be nowhere close to conclusive without finding a chassis lift and conducting an exhaustive search to fill in the circumstantial evidence of casting numbers and dates.

Case in point: At Kissimmee in 2020, Mecum offered a 283/283 fuel-injected Chevrolet 150 two-door sedan in the famed “Black Widow” colors of the specials built by SEDCO for NASCAR competition. It was represented as matching numbers and the authentic-looking block stamping, F508EK, was appropriate for the vehicle’s specification and coincident with its late chassis number, VA57F242813 (June production in Flint, Michigan, although other SEDCO Black Widows were assembled in Atlanta.) It failed to sell at a hammer bid of $85,000 and later sold twice at other Mecum auctions (Indy 2020 and Kissimmee 2022) for $82,500, including commission.

A reasonable conclusion is that no one believed it was a “Black Widow” after piercing the fog of matching-numbers attribution, which can most generously be interpreted that the F508EK engine number is a correct one for a 283/283 Fuelie.

Inference is not proof, and in the world of matching numbers proof is elusive, if it exists at all. The caveat for any emptor is research, more research, and then, when the money gets serious, to find and pay an expert for an in-depth report.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

In your article you noted” None of these sources, however, reference engine numbers,”

This is incorrect for Canada built GM vehicles . Vehicle Vintage Services has the exclusive rights to GM Canada data and does identify engine numbers. This is how I found the original engine for my 1968 Chevelle SS396 convertible.

No such luck for me, my Ford Flathead 8RT is Canadian, but the numbers stamped on the block apparently do not disclose the year of manufacture or anything else. They appear to be arbitrary, as their are no known records for them. (sigh!) So, it is a puzzle/gamble for me to order parts for it as I don’t know if it is 49/50/51/52 manufacture.

Matching numbers can be a disappointment too…. Like an ‘81 Turbo Trans Am where the 301 one is long gone and has been replaced by a strong old Pontiac 400

Mot sure all would be disappointed there.

Not sure all would be disappointed there.

Numbers matter in some cases and not in others. A Checker is a Checker pretty much no matter what.

But in cars like a Corvette a 327 car vs a 427 car can be thousands of dollars. If you don’t want to over pay for a fake numbers matter.

In some cars like at Olds the records were lost in a fire so you are on your own if a car is a 442 or clone. But Pontiac has the records to help confirm you are buying the real thing.

The more rare and high priced a car is the numbers become a factor but in many others it becomes less important.

I just hate seeing people over pay for clones that are miss represented.

Also the more original the car is the better it is true to what it really is. It just helps the buyer protect his investment if he is getting into specific cars.

RE: “A ’70 Mustang Boss 302 will have a “G” in the fifth position for the 302/290-hp V-8. Those codes should coincide with what’s under the hood. From there, it gets more circumstantial.”

NO! There is nothing “circumstantial” about VIN-stamped drivetrain components!

STOP PERPETUATING THE MYTH THAT FORDS CANNOT BE NUMBERS MATCHING!!

The National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966 was a Federal Law that went into effect Jan. 1, 1968 (you can read it here: https://uscode.house.gov/statutes/pl/89/563.pdf). The gist of it is that manufacturers had to be able to prove that they/their components are in compliance with the Safety Act, and thus be able to issue recalls on components (if necessary).

This translates to all manufacturers finding it necessary to imprint the vehicle VIN on all engine and transmissions as of Jan. 1, 1968. Ford complied as required. However, prior to 1968 Ford was typically imprinting VIN stamps only on engines and transmissions for “high performance” applications (it is believed this was closely related to theft deterrence and warranty claims).

Anyone who follows Ford products built after 1968 will know for a fact that the engine and transmissions were supposed to receive a partial VIN stamp. This stamping was typically truncated to only include model year, factory code and the sequential 6-digit portion of the VIN number. So you might end up with something like “0F513786” stamped on the engine and transmission ~ which would match the appropriate portion of the VIN on the dash and door tags, as well as the chassis shock towers.

Keep in mind that the stamping was all done by hand, so mistakes happened: mis-stamped digits, double-stampings, light stampings that are almost unreadable, etc.

For Ford, the stamped locations will vary somewhat depending on the engine and transmission type. Below are the common places to look for them;

– Most engines were stamped on the back of the driver’s/left side of the block, although sometimes the head was stamped instead (difficult to see without proper tools).

– Boss 302’s were stamped at the top center of the block along the back edge of the intake manifold (easily found on the engine).

– Manual transmissions were typically stamped along the top of the front lip where the trans mates to the bellhousing (difficult to see with the trans in the car).

– Automatic transmissions were typically stamped on the top side of the main case (nearly impossible to see when the trans is in the car).

Fords from this era also typically have chassis VIN-stamps on the tops of one or both shock towers (or sometimes the inner fender apron). These are sometimes referred to as the “hidden VIN,” as they were usually covered by the fenders. These stamps may be a full or partial VIN depending on the model year, and were also done by hand (errors occurred but are not common).

Now, all that being said, yes “numbers matching” is often touted as a selling point – and rightly so! What I find significantly lacking are sellers that provide actual PROOF that a vehicle is numbers matching. If the seller makes the claim then they should be able to back it up with pictures of the VIN stamps! Unfortunately, the burden of proof is almost always on the buyer.

This photo shows the VIN stamps for a 1970 Ford product.

Top Left = Dash Tag, showing complete VIN.

Bottom Left = Door Tag, showing complete VIN.

Top Right = Chassis VIN stamps on left and right shock towers.

Center = Engine VIN stamp.

Bottom Right = Transmission VIN stamp.

[img]https://i.imgur.com/xlXQRae.jpg[/img]

I have to correct you on some of the statements about what information manufacturers kept. Packard kept chassis firewall, engine, and serial number information for all Post war vehicles they made. You can see this on the roster on the Packard Club website. My own 49 Club Sedan is on there and the information is correct.

I also just attended the 75th Anniversary of Tucker at the AACA Museum and the talks showed that items as mundane as the glovebox lid were stamped with the car #. Records were kept about what engine and transmission were installed for every Tucker. I imagine they weren’t the only ones.

At GM, Buick cars were identified by some of the numbers, but only the 1970 and 1972 cars have records. For some reason (I don’t remember what, but I am sure someone does and will post) the 1971 records are “missing.” If you have a 1970 or 1972 Buick GS, you can write the Sloan Museum and send them the information about your car and they will send you a certificate and a list of date of manufacture, engine and transmission, and other options, and dealer-delivered-to data. For example, in 1972, for the GS Stage 1 cars, there is a “V” in the VIN. The carburetor and distributor for Stage 1 cars had specific numbers for each year, and in 1972, there is a small green paper “dot” attached to the 7042242 carb.

With all factory cars of all makes, there are some records of the so-called “chalk” marks in various places. These might have been chalk, paint, or some other material such as paper that were placed on the cars when specific parts were installed and checked off so the car could advance to the next station. For example, there are many cars that have white or yellow marks on the firewalls, Buick’s have bands of colors on the driveshafts–other cars may, as well, of course, and so forth.

C-2 Corvettes, which have, arguably, the most fanatic group of followers of any popular marque, had a yellow paint blob on the steering box, and all kinds of marks all over the car. A fun fact–in early 1966, the gas tank lid had crossed flags with the upper left corner white. Later cars–there is a firm date for this somewhere–they changed and the upper left corner of the flag is black. Carbs and distributors and intake manifolds, etc., all had very specific numbers, and differentials had specific indicators as to the ratio inside. All engines had a kind-of-yellow (I think) paper sticker with two black letters attached to the passenger side rear valve cover area that indicated which engine the car had. Another interesting fact is that late 1966 cars on had the (optional) shoulder belt female bolt fitting installed inside the rear wheel well because they knew that the DOT was going to require shoulder belts on all cars soon. Finally, C-2 knock-off wheels from Kelsey Hayes were only available in 1965 and 1966. The DOT disallowed them starting in 1967, so Chevrolet made a bolt-on wheel that LOOKED like a true knock-off for 1967 models.

MOPAR fans know of many specific details for their cars as well, and they are almost as fanatic as Corvette people. Having been in the “hobby” for many years, I find some of this interesting and some of it silly. Does a “survivor” car have to have 196x air in the original (unusable) tires? Has the radiator fluid or various belts and hoses been changed? Are those the “original” T-3 headlights? Do you have a dated air cleaner filter or oil filter? Yes, it is a hobby, and yes, fakes are rampant, unfortunately, and I do enjoy it, but some of this stuff is just silly even though big dollars are associated with some of it. I always tell a potential buyer to have a professional survey done if they have questions and don’t happen to know the markings on every bolt on the car.

Finally, as we all know, none of these companies were making “classic” cars. They had production requirements, and stopping the line was a pretty serious event. SO, if the person bolting the doors to the car ran out of bolts, the runner dropped a new box that MIGHT be from a different vendor. So, a “factory” car might have two DIFFERENT bolts on the door hinges…what’s a serious car judge to do, right?

Cheers!

A side-effect developed when hi-performance engines required suitable upgrades to the rest of the vehicle; the presence and factory installation of those upgrades is a big “tell” regarding a car’s authenticity to factory spec. A boon to the #s-matching concern came when VIN references were applied to the engine & transmission. For most of the other components, date codes and correct applications address the likelihood that those components are original to the car. If there’s a “track sheet” or “broadcast sheet” for the car present – which told the workers what parts went on the car – that’s a huge plus. All that said, there are fake documents, re-stamped components, and even fake VINs out there, as dishonest people aim to cash in on the hobby. Buyers should do research and know their chosen marque’s characteristics before spending top dollar. Sellers should provide proof of authenticity, but of course that may sadly be at odds with their morals…

How many numbers matching articles are we going to get?

That number hasn’t been disclosed.

B^)

I had a 70 Ford Ranchero since new and had to put a clutch in it. Behind the flywheel on the block was a machined pad with the vin stamped. Other non high performance Fords also had a flat pad for stamping on the blocks. If I remember correctly the sixes were on the side of block

Sometimes for the sake of modern drivability we need to replace some components. I tried to keep my 69 Firebird original but I wanted a four speed auto trans instead of a 3 speed. Then someone might want fuel injection or electronic ignition or aluminum radiator etc. Are we trying to have a complete original or a modernized street car? It is up to the individual. Maybe the answer is that we just save all parts taken off. And yes, the crime is in the sellers who advertise a car being a certain model and components but are deceiving the buyer with a fake.

The author stated that “Matching” numbers didn’t exist, nor did they matter. In the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s”.

I currently own a 1932 Hudson Essex. During it’s restoration I found the VIN # stamped on the engine block, the front axle, the rear axle, the rear frame crossmember, the front frame rail, and the ID plate on the firewall.

Nuff said. … Gary

I have a Jaguar E Type that has matching numbers …. except the gearbox number ends in 33 whereas the chassis plate shows it ending in 35. All of the rest of the gearbox number matches. It is most unlikely that a previous owner has changed the original box for one that was two gearboxes earlier. Apparently it was not unheard of for the wrong box to be fitted to a chassis, or the wrong number stamped on the plate – whatever came first.

I had a 1934 Plymouth PE Deluxe Business Coupe from 1971 to 2000. During the restoration, I found the engine number stamped on the frame rail on the “hump” over the left rear wheel opening. Also have a 1969 Dodge Charger with the original drivetrain. I know because I ordered the car in 1969.