Media | Articles

Fakes, frauds and forgeries: Illegality in the collector-car market

This summer, a spicy story of automotive identity theft broke in Germany. One happy new owner of a $1.74M Mercedes-Benz 300SL went to register his yellow roadster, only to get the kind of news no car enthusiast ever wants to hear: Another 300SL with the same chassis number was already registered. Authorities assert that a fake car was created using the chassis number from the yellow SL, which hadn’t been to market in decades and was presumed lost. The investigation is ongoing, but noted restorer Kienle Automobiltechnik was searched a few months ago and investigators reportedly started looking for evidence of other duplicates in the shop’s past. Regardless of where the blame for the counterfeit SL lands, the car highlights a rare but cautionary scenario that’s hardly the first one of its kind in the collector-car world.

Colloquially, we refer to our huge (but sometimes surprisingly small) world of collector cars as “the hobby.” Fair enough. It is our hobby. Enjoying automobiles is how many of us make friends and spend our free time, driven by that powerful cocktail of passion and nostalgia. It’s fun, and it’s supposed to be.

But let’s face it: “The hobby” isn’t the same thing as beer-league baseball or knitting. There’s a lot of money involved in classic cars, not just in the values of our vehicles but in the industries built around selling them, restoring them, servicing them, financing them, insuring them, even celebrating them via massive, expensive events. Hagerty’s Automotive Intelligence team estimates that there are 45 million collector vehicles in the United States together worth roughly $1 trillion. In 2022, collector-car auctions in North America alone totaled $3.48 billion.

As with any large, lucrative industry, collector cars are susceptible to questionable behavior, from shady to straight-up criminal, from minor fibs to full-blown fraud. Given the collector-car market’s own complexities, and since most of a vehicle’s value boils down to two things—appearance and history, the latter verified by documentation and occasionally forensic examination—our precious rides can be particularly susceptible to fakery and even to fraud. Things like missing chassis numbers are what Hagerty Price Guide publisher Dave Kinney calls “fertile ground for the criminal mind.”

Think about it. A car can look like a million bucks—literally—but if it is really a well-executed fake with phony paperwork or just a replica, it’s only worth a fraction of that amount.

While the shadiest stuff is rare, it is still common enough that some insurance providers have specialized groups to investigate questionable and suspicious claims. Legal disputes are common enough that there are attorneys who specialize in cases that involve collector cars.

Bryan Shook runs the aptly named Vintage Car Law in Pennsylvania, though his work takes him across the country. Many of the cases he sees don’t necessarily involve fraud, which requires a representer’s knowledge of falsity and has a high burden of proof. Instead, cases involving cars that aren’t actually what they seem are more common.

“When I started in 2005–06,” says Shook, “we were seeing misrepresentations, with a big emphasis on muscle cars with particular option packages. People were passing off clones, like a base-model Pontiac made into a GTO, sometimes even with convincing paperwork and restamped motors.” Those practices aren’t as common today, but “some of those cars have been passed around and sold so many times as real when they’re actually ancient fakes. They can go through multiple sellers without anybody knowing it’s a fake, so there’s identity issues with them today.” Often, an “ancient fake” muscle car won’t be revealed until it’s restored, when things like trim holes from a lesser model or cuts in the body with numbers transferred to it reveal themselves.

“There are restorers who will tell you when they find a problem like that, and there are restorers who won’t tell you, who just want their client’s money. And if they don’t say anything, are they complicit? My answer is yes,” says Shook.

In addition to fakes and clones passed off as the real thing, there’s the issue of cars—and particularly race cars—where two vehicles can claim the same identity. An old joke goes something like: “15 were built, of which just 25 are known to exist.” There are also cases where one car can be changed so much over time that there are questions of its authenticity, à la the Ship of Theseus paradox.

A Jaguar D-Type, chassis XKD530, had an active and interesting life racing not just on the road but also on ice and sand in Finland, and even in the USSR. Years later, after the car had been damaged, one car had been built up around the original front subframe and bodywork, while a second car had been built up around the original monocoque and powertrain. The only real solution, other than a legal dispute, was for one person to buy both cars and restore them back into one, which is what happened in the early 2000s. Eventually, the car sold post-block at Amelia Island in 2015 for $3.675M. For comparison, in spring 2015, a no-stories D-Type in #2 (Excellent) condition was valued at $5M.

Not all such stories have that kind of happy ending, though. A Ferrari 250 Testarossa, chassis 0720 TR, burned up in 1965 when lightning struck the Missouri barn that was storing it. The frame was saved but later discarded in a ravine and eventually sold to an English collector who had an entire car built up around it. Then a second Testarossa frame turned up in Italy claiming the same chassis number. It, too, was faithfully built up into a fully functioning 250 TR and consigned to a Swiss auction in 2001. Before it crossed the block, however, it was slapped with an injunction and pulled from the auction. The result is that the chassis from the ravine is the only one with real claim to be chassis 0720 TR. The other is, in effect, a replica.

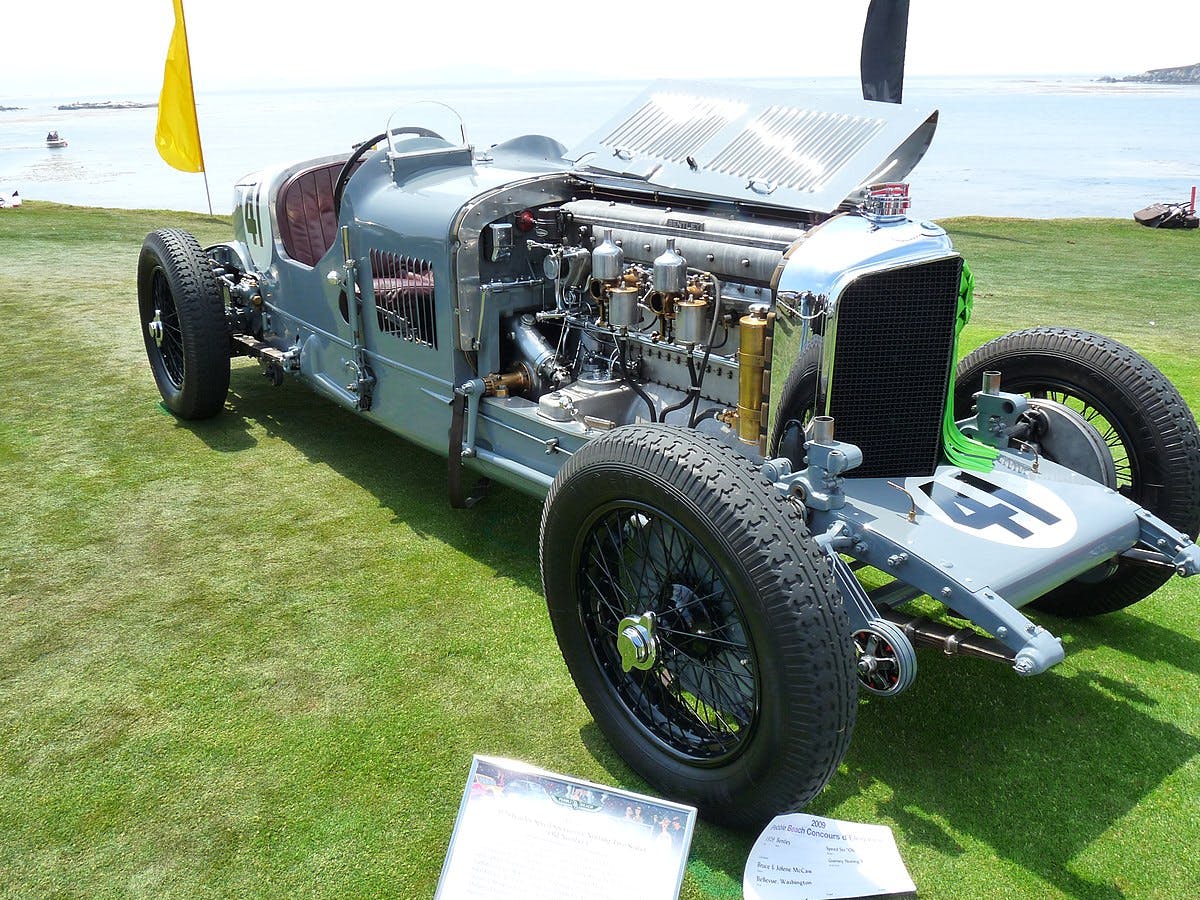

Consider also the case of the 1929 Bentley “Old Number One.” It has a spectacular racing history, including overall victory at Le Mans in 1929 and in 1930, but the vehicle also evolved continuously throughout its racing career, was extensively rebuilt multiple times, and was even involved in a fatal crash in 1933. But Old Number One does have a continuous, well-documented history. In 1990, it became the subject of a case in front of the Royal Courts of Justice. The car’s owner had agreed to sell it to a company in exchange for a combination of assets and cash valued at £10M, but the would-be buyer withdrew from the sale after doubting the car’s authenticity. The result of the case was that the car is deemed the “direct descendant” of Old Number One and that no other car can claim its identity.

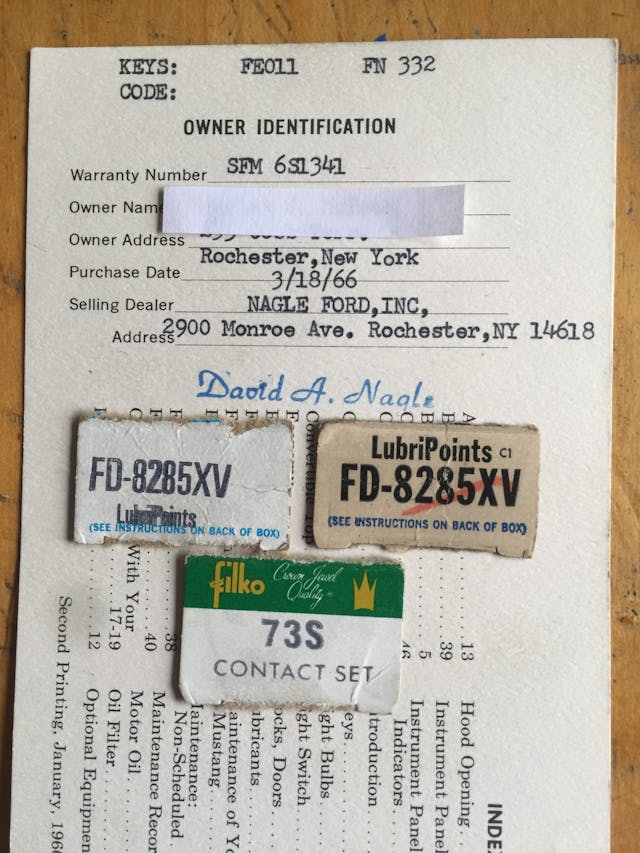

More common and more nefarious than these edge cases of historic cars is tinkering with paperwork and VINs. This is especially problematic if a VIN is “portable,” as Shook calls it. “On some early cars, a VIN can be just two Phillips head screws attaching it to the body. My 9-year-old son could have that off in three minutes.” Or, on some other cars, “the VIN comes right off with the dash pad, so think about how easily that can be moved to another car.”

Shook also says he regularly comes across private Facebook groups advertising “tin” and “paper,” referring to VIN plates and titles. “There are fraudulent, fake titles being sold on the internet every day.” There are innocent reasons why one might not have a VIN or title, like an old abandoned truck sitting outside or an inherited vehicle that has no documents, but “when there are entities out there just wholesale providing these services without checking on anything, they’re contributing to or perhaps aiding and abetting fraud,” Shook says.

Bigger and higher-profile cases of genuine wrongdoing are rarer, but people have been caught over the years, sometimes to sensational headlines.

In a case from Germany in 2020, the public prosecutor’s office of Aachen brought charges against three men, including a well-known restorer and former Porsche employee, for fraud involving building up Porsche race cars from the ’60s using spare chassis and parts, forging paperwork and race histories, and selling them—sometimes, for millions of euros. The main defendant in the case was alleged to have faked more than 30 Porsches.

Of course, there are also just good old-fashioned scams, in which two parties agree to a sale, the buyer pays for a product, and the seller simply takes off with the money because there was no actual product to begin with. Internet-based transactions, particularly in the last decade, have facilitated this activity. From 2016 to 2018, for example, a group of fraudsters from Eastern Europe and Central Asia duped enthusiasts out of more than $4M. They created convincing ads online for classic cars they didn’t really have and directed would-be buyers to wire money to a transport company that was actually the fraudsters’ own fake shell company. A total of 25 defendants in the Southern District of New York case were charged with conspiracy to commit wire fraud and conspiracy to commit money laundering.

This isn’t a totally isolated case. More recent scams seen by Hagerty’s Special Investigations Unit team include websites that swipe photos from popular online auction listings, digitally manipulate ones showing the VIN to alter it by a digit or two, and then try to pass the whole thing off as a genuine vehicle listed for sale to lure buyers who may not be doing their homework.

Along with good old-fashioned scams, there’s good old-fashioned insurance fraud. Remember Andy House? Back in 2009, in the early days of camera phones, the Texas salvage yard owner was famously caught on video driving a Bugatti Veyron straight into a Gulf Coast lagoon, leaving the engine running and claiming he was distracted by a (nonexistent) low-flying pelican, before having his $2.2M insurance claim denied. He wound up serving over a year in prison for the act.

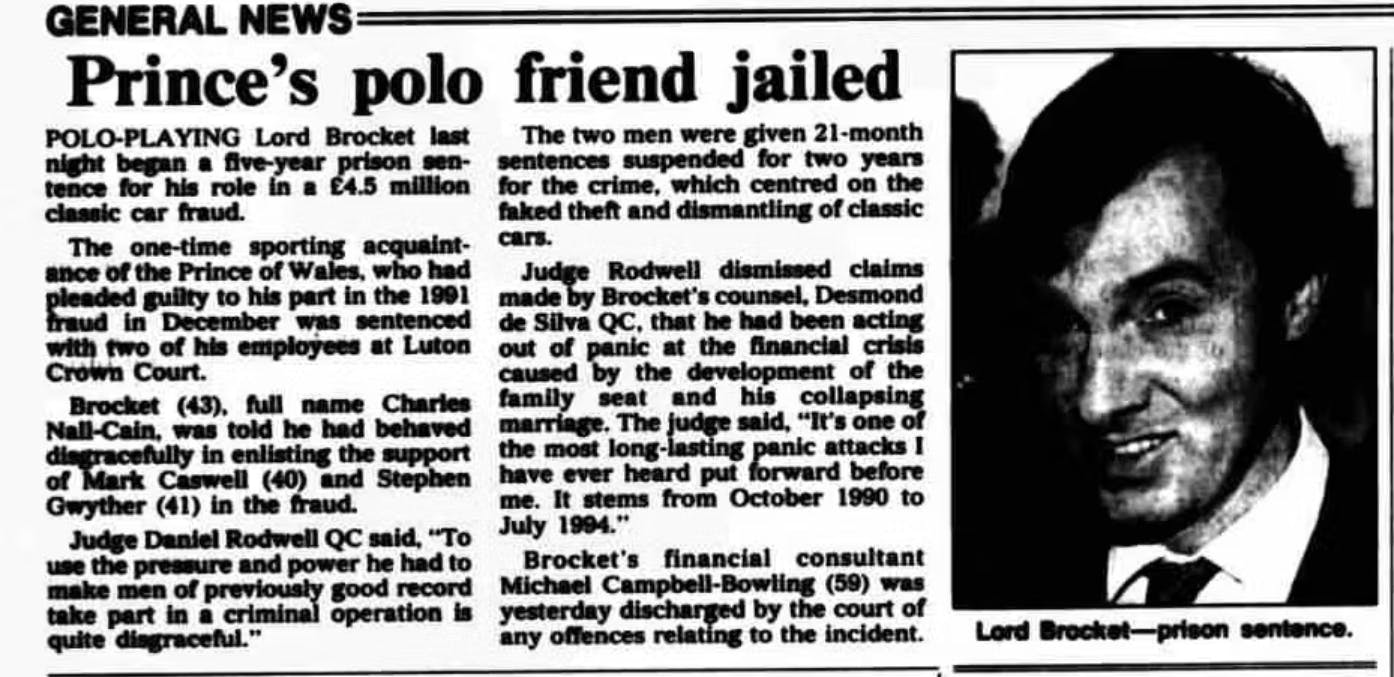

Maybe the most famous case of collector-car insurance fraud, however, comes not from a Lone Star auto parts jockey but from English nobility. Charles Ronald George Nall-Cain, aka the third Baron Brocket aka “Brocket the Rocket,” had by the end of the 1980s amassed a collection of a few dozen blue-chip classics through a bank loan and was pulling in revenue by using his ancestral home of Brocket Hall as a conference venue and golf course. But when the early 1990s recession hit, the classic car boom turned into a bust and the big wigs weren’t booking Brocket Hall like they used to.

Then, in 1991, three of Lord Brocket’s classic Ferraris and his Maserati Birdcage, each of which was insured for more than it was worth after the downturn, were reported stolen. The circumstances were suspicious, but nobody found any evidence of wrongdoing. Until 1995, that is, when his estranged wife was being questioned by police about a suspected forged prescription and spilled the beans on her husband’s insurance fraud. The Italian classics had not, in fact, been stolen. Instead, Lord Brocket and his mechanic had destroyed the bodywork while dismantling the rest of the cars and shuffling off the parts to a west London storage unit in hopes of rebuilding them one day. Lord Brocket was sentenced to five years in prison. In the end, he served less than half that time.

There are also cases of trying to get a loan against valuable assets, like cars, that people do not own. Ricky Prince, owner and operator of North Texas Muscle Cars, Inc. padded his financial statements to secure credit with cars he didn’t actually own, including a 1963 Corvette, a ’74 DeTomaso Pantera, a ’67 Chevelle, and a ’38 Ford hot rod. In 2012, he pleaded guilty to bank fraud and money laundering, was sentenced to 36 months in prison, and ordered to pay restitution of $1.46M.

Illegal activity has even gone on in a big-name auction house. Founded in 1919 as an antiques dealer, Coys became a leader in the collector-car auction space during the 1980s. In 2004, however, after a buyout Coys of Kensington Automobiles Ltd. (as it was then known) went into administration, and a new company emerged with the same name and address. A long list of legal disputes and complaints followed, until Coys went into administration again in 2020, with 95 creditors owed nearly £6M. Many of their stories are detailed in this great piece on PreWarCar. Coys was allegedly paying previous sellers from previous auctions with money from the next ones—the basic recipe of a Ponzi scheme. There were also legal claims of sales without authorization and sales of vehicles at lower prices than a consignor had stipulated.

One such story involves a collector selling his Lamborghini Miura via Coys, never receiving his money, and instead being asked a year later if he would accept a Porsche 959 as compensation for the payment. He took Coys up on the offer—a Porsche was better than nothing—but the 959 was seized by German police because Coys didn’t actually own the car. The collector’s legal complaints eventually led to the German police showing up to Coys’ Techno Classica auction, slapping handcuffs on company director Chris Routledge, and marching him away from the rostrum. In 2020, a new entity was founded that, for some reason, uses the same name (Coys of London Automobiles Ltd.) and showroom.

Even household names can get screwed in this business. Jerry Seinfeld, arguably the second-most famous car-guy comedian, is a known Porsche fanatic, but even he wasn’t immune from getting burned on an allegedly fake P-car. In 2016, a 356A GS/GT Carrera Speedster he consigned to auction sold for $1.54M, reportedly after buying the car four years earlier for $1.2M. The firm that bought the car from Seinfeld then sued the comedian in 2019, claiming that the Speedster was not an authentic GS/GT. In a legal tit-for-tat, Seinfeld turned around and sued the dealer he had bought the car from “to hold European Collectibles [the original dealer] accountable for its own certification of authenticity, and to allow the court to determine the just outcome,” according to Seinfeld’s attorney. In the end, both cases were settled, although the precise terms of the settlement are not known.

The most recent case of celebrity-owned car fraud to make the mainstream news involves singer Adam Levine. According to a federal suit in California, he traded a 1968 Ferrari 365 GTC and a 1972 Ferrari 365 GTC/4 plus $100,000 to dealer Rick Cole (who was actually the first to auction collector cars in Monterey) in exchange for what was supposed to be a 1971 Maserati Ghibli 4.9 Spyder. Levine later learned that another car with the same VIN resides in a collection in Switzerland. Levine’s car certainly looked like a genuine 4.9 Spyder, one of 25 such cars built, but the suit claimed that numbers stamped on the chassis and engine appeared incorrect. It went on to say that Cole had fake documentation on the car and knew that the car wasn’t a genuine 4.9 Spyder (it is likely either an original Spyder fitted with the 4.9-liter engine from a different car or a Ghibli coupe converted into a Spyder). According to the case cited in the Los Angeles Times, Cole even tried to discourage Levine from selling the car on, for fear he would learn the truth about its authenticity.

Finally, there’s also straight-up theft. We all have that friend who can smooth-talk their way into big favors or private events, but what about someone who can talk their way into stealing three Ferraris? Enter Tom Baker, JetBlue pilot by day, supercar thief on his days off. His first adventure into car swiping was convincing a Ferrari dealer to let him take a 328 GTS for a test drive, but he took off with the car and never returned. Next, he charmed his way into a Testarossa from a Long Island dealer using the same tactics. Then, he walked into a dealership in Philadelphia, claiming to be a California tech CEO just flying in to see the F50 they had for sale.

At the end of that test drive, when the salesman got out of the car to switch places and drive back to the dealer, Baker stayed right in the driver’s seat and stomped on the gas, the one-of-349 Ferrari’s 513-horsepower V-12 singing off into the distance. A few years later in 2008, an ER doctor had bought the F50 from Baker and only learned he had just bought a stolen car after contacting Ferrari regarding the car’s VIN. Baker wound up turning himself in and was sentenced to eight months in prison. The FBI impounded the F50, only for an agent and a DOJ attorney to crash it into a tree and total it while transferring it into storage.

These are all high-profile stories, but a less well-publicized case that nevertheless established what Shook calls “very significant precedent” is Adams v. Brenton in 2018. Wes Brenton had advertised a 1968 L88 Corvette (one of 80 built) for sale, and Cory Adams bought it for $245,000, intending to have it professionally restored. When he called Corvette specialist Kevin Mackay to inquire about restoration, Mackay informed him that several months prior, he had told the seller that the car was not a genuine L88. Called as an expert witness, Mackay also testified that, in its current state, the car was actually worth about $10,000. Adams sued and won, with the court adjudging Brenton liable for compensatory damages of $235,000 plus interest and attorney’s fees of $40,835.35. Because of that case, “if an expert looks at a car you’re selling and tells you something negative about it that’s substantial, like that it’s fake, you have to disclose that to a potential buyer even if you disagree with that,” according to Shook.

Everybody’s first piece of advice when shopping for a classic car is “do your research—do all of your homework.” These stories make it abundantly clear why people say that. It can be the difference between spotting a fake and buying one. There are bad actors out there as well as genuine misunderstandings, and both can burn you. Taking the extra steps to validate and verify (which admittedly can be both expensive and time-consuming), or consulting a helpful expert are not things that anybody ever regrets.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Hagerty has apparently bought into the Black Ghost” hoax.

?Has Hagerty been involved in, or a victim, of such misdeeds – surely you must be at risk. Could a Marketplace auction be involved? In your brief lead-up postings + the free-for-all of an evolving on-line auction, is there really enough info to guarantee a buyer’s safe educated bid + purchase? Perhaps venial, but recently a Ford GT was auctioned with definite emphasis on a trivial 2015 accident (~$10k damages), while finessing a prior major 2010 accident ($146K repair) – while the 2015 small accident was discussed – the 2010 invoice was just posted but not openly mentioned at first, it was long + confusing (?wrong color car + date), and even called erroneous. Just prior to auction, 2 accident were finally acknowledged – sorta. **>> maybe Hagerty should be in the business of officially documenting classics for a modest fee, to protect both “the hobby”+ everyone involved. Maybe there should be insurance against fraud.