Media | Articles

Did This Progressive-Era Couple Invent Car Collecting?

When did “the hobby” of car collecting really start?

There’s a famous quote, attributed to Henry Ford: “Auto racing began five minutes after the second car was built.” Can we say the same of auto collecting? Did it start as soon as someone bought their second car?

Probably not, and the Ford quote isn’t literally true, either. But the concept and ethos of car collecting, which grew in the 1930s and 1940s, goes back a lot further than many realize. By 1918, when the Western Front was still noisy and long before most popular “classic” cars had even been conceived, an East Coast couple named Larz and Isabel Anderson had already assembled a group of nearly a dozen motorcars. The Andersons kept acquiring cars well into the 1930s, carefully selecting for different styles and purposes, consistently maintaining them, and treating the vehicles almost like the children they never had.

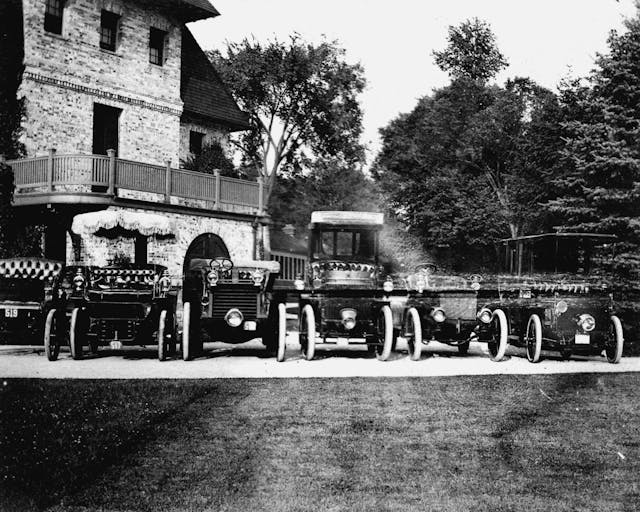

Nobody would have called it a “car collection” then, but the Andersons’ approach to buying, enjoying, and preserving their automobiles is familiar to any 21st-century collector. And the cars are still around today, billed as America’s oldest car collection. It isn’t just their age that’s impressive, either; while not a huge group, the Andersons’ is a curated one that represents nearly every type of period drivetrain configuration and body style. Many of the vehicles were among the most expensive of their type when new. Most importantly, they are all completely original, have never changed hands, and still reside in their original garage, now known as the Larz Anderson Auto Museum. It may be America’s oldest car collection, but no other group of cars in the world is quite like the Andersons’, and 100 years ago it was way ahead of its time.

The Andersons

Larz Kilgour Anderson was born in 1866 in Paris, then raised in Cincinnati. He had the bluest of blue blood. His great grandfather witnessed the Boston Tea Party, was a captain in the Continental Army, and married William Clark’s (of Lewis and Clark) sister. His father was wounded three times in the Civil War and was a good friend and classmate of Robert Todd Lincoln, son of the president. After Larz dropped out of Harvard Law School in 1891, it was through that connection that he snagged a job at the American Legation in London. So began a diplomatic career, and after three years in London he was appointed first secretary of the American embassy in Rome. While in the Italian capital he met 18-year-old Isabel Weld Perkins while she was on her Grand Tour. A flurry of love letters followed, he proposed in Boston later that year, and the couple were married in June 1897. It was a “simply planned and admirably executed wedding,” according to The Boston Globe. Larz and Isabel rode away from the wedding in a horse-drawn carriage. A year later they became enchanted by the horseless carriage.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Although the couple’s collection and museum are now named after Larz, Isabel was arguably the more interesting of the pair. She was certainly wealthier. Born in 1876 to a New England family that traced its Massachusetts roots to the 1630s, she inherited part of her grandfather’s shipping and railroad fortune in 1881, when she was just five years old. Sources vary on the size of the fortune that went to Isabel, but it was well into the millions, and she was groomed for a life in high society in Boston and Newport.

Their Life and Home(s)

After getting married, the Andersons traveled. Together, they went on more than 70 trips to over 50 countries, colonies, and territories, and wherever they went, they acquired art and décor for their homes. They were voracious but also careful and deliberate, an approach they took when acquiring motorcars as well.

Larz’s diplomatic career peaked in the early 1910s. In late 1911, he became the United States Minister to Belgium and, after a year, Ambassador to Japan. The Andersons loved Japan, but after William Howard Taft lost the 1912 presidential election to Woodrow Wilson, Larz resigned and left just a few months after arriving. The Andersons then spent much of the rest of their marriage traveling, collecting, entertaining, and improving their properties.

Isabel, meanwhile, was never idle. Aside from high society life, philanthropy, and traveling the world, she supported progressive causes like prison reform and higher education for women. During World War I, she volunteered as a nurse with the American Red Cross and spent nearly a year near the Western Front. Isabel was also the first woman in Massachusetts to receive her driver’s license.

She was a prolific writer, too, publishing some five dozen works of poetry, nonfiction, short stories, children’s literature, musical theater, and travelogues. In some of her travel books, she devotes entire chapters to motoring, like 1915’s The Spell of Belgium (“Brussels is ideally located for the motorist”) or 1914’s The Spell of Japan (“Motoring is just beginning to be popular in Japan … Only in a city like Tokyo or Yokohama is it worth while for the resident to have a car the year round”).

When they weren’t abroad, the Andersons split time between three East Coast properties. One in New Hampshire was a getaway from society life. Their mansion on Massachusetts Avenue in Washington, DC, meanwhile, was almost entirely for society life and one of the most fashionable addresses on the DC social circuit. Prominent guests included the Vanderbilts, Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., John J. Pershing, and Douglas MacArthur, plus a slew of royals and nobles from abroad, including King Prajadhipok and Queen Rambhai Barni of Siam as well as Prince Andrew and Princess Alice of Greece, whose son would go on to marry Queen Elizabeth II.

For summers, there was a second foothold in New England. Weld, a sprawling family estate Isabel acquired in the 1890s, was located in wealthy Boston-adjacent Brookline, Massachusetts. The Andersons had it transformed into something palatial. The main residence, a 25-room mansion at the top of a hill overlooking the city of Boston, more than doubled in size under their tenure and housed various art and artifacts collected on their travels. A glorious Italian garden designed by famous architect Charles A. Platt sat adjacent to the mansion, as did a smaller but equally impressive Japanese garden, cared for by a full-time gardener from Japan. The Andersons’ penchant for collecting extended beyond art and automobiles, as Weld housed one of the largest groups of bonsai trees in the United States.

According to the biography Larz and Isabel Anderson: Wealth and Celebrity in the Gilded Age, between 1900 and 1940 an estimated 200 people lived and/or worked at Weld. The annual budget for the Brookline estate averaged over $200,000 (not adjusted for inflation). In addition to gardens and housekeepers, the Andersons also had a stable of horses, carriages, and cars to look after.

Their Cars, 1899–1918

Almost as impressive as the Andersons’ mansion was their buff brick two-story carriage house on the grounds of Weld. Modeled after the Château de Chaumont-sur-Loire in France, it was built in 1888. This was well before any widespread adoption of the motorcar, so at first the building housed dozens of carriages as well as horses in its handsome wood interior, separating them by elaborate stalls divided by marble panels and labeled with gold-lettered nameplates. The Andersons never stopped keeping horses and never got rid of their carriages, but by the turn of the century they were already enthusiastic early adopters of the automobile. They bought one nearly every year, gave it a name and a motto, kept it maintained by chauffeurs and mechanics, then retired it once it became obsolete. They rarely, however, got rid of anything.

The motoring bug first bit the Andersons in 1898, while they were in Paris. At the time, France led the world in automotive production and use, and these American aristocrats were captivated by the horseless carriages buzzing around the capital city. Motorcars were still very much luxury goods for the wealthy, but Larz and Isabel could very much afford one, and ordered their first car from Cleveland’s Winton Motor Carriage Company as soon as they returned to the States. The Andersons were among Winton’s first customers, and the car was a true horseless carriage with a sparse phaeton body, tiller steering, and simple single-cylinder engine. Since the Winton was their first car, they nicknamed it “Pioneer” and gave it the motto “It Will Go.”

Larz and Isabel ordered their second car in France in 1900 from a company called Rochet-Schneider. Largely a copy of a Benz design with a big single-cylinder engine driven by a leather belt, it also had a strange (and distracting) “vis-à-vis” seating arrangement, in which the passengers rode on the front seat and could either face toward or away from the driver. Theirs didn’t just come with funky seats; Rochet-Schneider provided a chauffeur who moved back to Brookline with the Andersons and lived with them for several years.

Like with many early automobile owners, speed quickly seduced Larz. By his third car, in 1901, he was already racing. The Winton Bullet, which the Andersons nicknamed “Buckeye,” is a 40-hp, two-cylinder racer. Four were built, and another became famous when Alexander Winton raced it against Henry Ford’s “Sweepstakes” car in 1901. Although Winton seized an early lead, the car broke and Henry Ford then used the prize money to start the Henry Ford Company.

With three properties to go between, the Andersons also wanted a car for longer-distance trips, and for this purpose they acquired their first and only steam car. Although the Stanley Motor Carriage Company built steamers in nearby Newton, MA, the Andersons went back to the French in 1903 for something larger, heavier duty, more complex, and much more expensive. Their Gardner-Serpollet had a four-cylinder engine when other steam cars had two, and the company’s patented flash boiler allowed it to come to steam in about 90 seconds, when other steam cars could take about half an hour. It also came with both summer and winter bodywork.

By their fourth car, a 1905 Electromobile from England, the Andersons had every type of propulsion—gas, steam, and electric—in their possession. The Electromobile, nicknamed “Bringer of Happiness” and given the motto “It Goes Without Saying,” was a typical early electric, and similar cars were popular in American cities by this time.

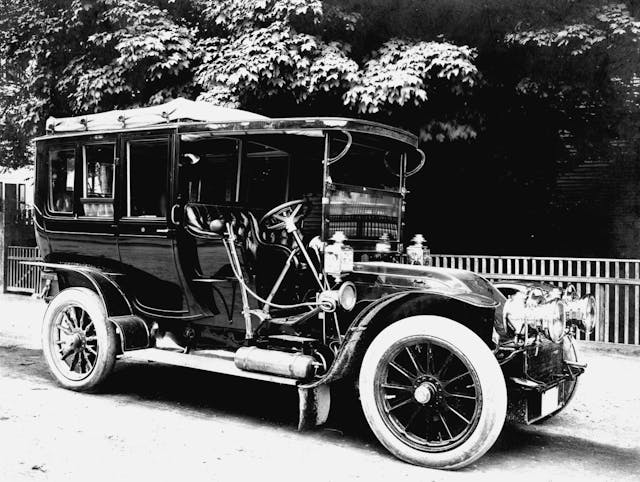

Their next car, however, was not at all typical. The 1906 Charron-Girardot-Voigt (CGV) was almost as much early motorhome as it was early motorcar. The Andersons commissioned it with long-distance travel in mind, and its build was exciting enough to prompt an announcement in a French newspaper, which called it “the most comfortable and most elegant automobile one could imagine.” The rearmost seat converted into a bed, and two smaller seats flipped up for a wash bin. Since these were the days before interstates and rest stops, there was a toilet as well. With dual chain drive and a 75-hp T-head four-cylinder engine, the car could do 75-to-80 mph despite its immense size.

The CGV was the Andersons’ most expensive vehicle: It reportedly cost $23,000 to build. The Ford Model T, introduced a few years later, cost well under $1000. To be fair to CGV, though, Model Ts didn’t come with a toilet.

By 1907, Larz’s 1901 Winton Bullet would have already been obsolete in terms of high performance, so that year while on vacation in Europe he bought a Fiat and had it bodied in New York. The 11-liter, 65-hp six-cylinder made it one of the fastest cars money could buy in 1907, so the Andersons nicknamed it “The Conqueror” with the motto “No Hill Can Stop Me.” An odd flex today, but hills stopped many a motorcar in the 1900s. They again followed up a sporty purchase with something completely different in 1908—a Bailey Electric Phaeton Victoria. With an open body resembling a carriage and early collaboration with Thomas Edison, Baileys were built in Massachusetts and boasted 100 miles of range. Early electrics were often marketed to women because of their ease of operation, and the Bailey was Isabel’s favorite car. Its nickname was “The Good Fairy;” its motto was “Always Ready and Faithful.”

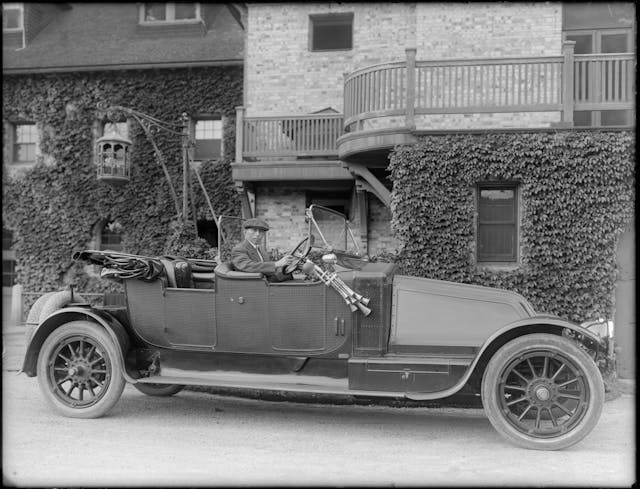

The Andersons went back to the French for their next car in 1910—a Panhard et Levassor—as a formal landaulet city car while Larz was at his diplomatic post in Belgium. In 1911 they bought an example of the Harry Stutz–designed American Underslung, which was noted for its distinctively low chassis and marketed as “The Car For the Discriminating Few” (the American Underslung passed into Briggs Cunningham’s ownership in the 1940s). They went French again in 1912 with their Renault Victoria Phaeton, distinguished by its sloped nose, radiator placement behind the engine, brass accents, and special canework on the sides of the Vanden Plas–built body. A similar Renault went down with the Titanic that same year.

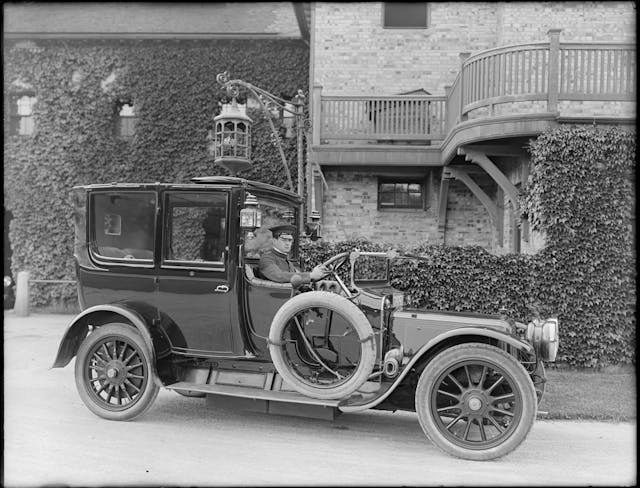

In 1915, the Andersons acquired a Packard Twin Six. In a time when even high-end cars had six-cylinder engines, Packard introduced the first mass-produced 12-cylinder car. Bodied by Brewster & Co. in New York with fairly conservative sedan coachwork, Larz and Isabel bestowed upon theirs the appropriate nickname of “12 Apostles.”

Their Cars, Post-World War I

After the war, when Isabel returned from Europe, their car-buying habits changed. The Andersons chose vehicles that were more conservative in style, with more muted colors and a more utilitarian nature, including multiple station wagons and trucks. The vehicles were generally less flashy and the Andersons were less likely to keep them.

Among the ones they did keep was a 1924 Renault Torpedo that, in contrast to their grand coachbuilt Renault from 1912, was a tiny and lower-priced open car. Next was a 1925 Luxor, built in Massachusetts. Luxor was not a luxury carmaker, and indeed Luxor configured almost all of its cars as taxis. The Andersons may have been the only people to order one for personal use. The final car that still remains with the Anderson collection was the 1926 Lincoln, an expensive car at $5300 that nevertheless wore a conservative sedan body and, like the Renault and Luxor, modest all-gray paint. As a nod to the 16th president, the Andersons nicknamed it “The Emancipator.”

Their Cars as a Collection

Larz died in 1937 at age 71. Isabel donated Anderson House in Washington, DC, to the Society of the Cincinnati (sort of a male equivalent to the Daughters of the American Revolution), and the house still serves as the organization’s headquarters. Meanwhile, she retired to the Brookline estate and seriously reduced expenses. According to their biography, Wealth and Celebrity in the Gilded Age, the estate’s annual budget shrank from $220K to $77K a year. Naturally, the lavish gardens wilted a bit and the majesty of the place diminished. She did not even consider, however, selling off the group of early motorcars, even though many were not in use.

When Isabel passed in 1948, she willed the estate to the Town of Brookline. Unable and unsure how to maintain the entire property, the town turned it into Larz Anderson Park while the mansion, after some years of disrepair of vandalism, was torn down in the 1950s. The carriage house, meanwhile, was still gorgeous. The town turned over its contents to the Veteran Motor Car Club of America (VMCCA), which opened a museum there in 1948 and used the carriage house as its headquarters until 1966. Prominent early collectors like Henry Austin Clark and James Melton were members at the time. Today, 14 of the Andersons’ exceedingly rare, all-original, single-owner, single-home automobiles make up the permanent collection of the museum, which has become a regional hub of automotive culture and pursues its mission of “supporting the community through educational outreach and the preservation of our permanent collection of early automobiles.”

Appreciation for early automobiles and early car collecting started to take off in the 1930s and the post-World War II years. The VMCCA was founded in 1938. The Antique Automobile Club of America (AACA) started in 1935 and the Classic Car Club of America (CCCA) in 1952, and judged car shows with both clubs grew in popularity during the 1950s. As early as the 1920s, though, the Andersons were already opening up the carriage house for tours and viewings of their “ancient” vehicles. Their originality and preservation were valued long before preservation became a prevailing trend in the collector car hobby, and they were carefully kept even though there was yet little interest in early pioneering automobiles. Evan Ide, in The Stewardship of Historically Important Automobiles, writes that “Isabel spoke of the fact that nearly all styles and types of early car were represented, and that the overall collection told the story of the development of the motorcar.”

Indeed, the automobile advanced more rapidly in the early 1900s than at any other time. Today, a 15-year-old car is still perfectly usable. In 1920, a 15-year-old car was completely outclassed and obsolete. For the Andersons to keep and maintain their early cars was both incredibly forward-thinking and a great service to this little hobby of ours. Thank goodness they did.

In this era it was not unusual for the old money rich to own a number of cars and types of cars. It was a new technology and many dabbled in it due to interest and status.

Much like today someone owning an Enzo and Bugatti along with a Bentley and Mclaren.

What is unusual here is how this collection was kept together all these years. So many of the ultra rich homes were torn down as no one could afford to keep them up. Collections like this were scrapped in WW2 as most were not seen as assets and oten many were in disrepair.

It is rare to find cars like this and still in original condition and together. That is really amazing.

Perhaps one of the reasons that the collection was kept together was that the Andersons had no children or other heirs. There was no need to monetize the Anderson’s collections and estate to support the next generation.

Contrast that with what happened to the Mullen Collection. Peter Mullen’s incredible collection of French cars and all things Bugatti was sold off within months of his passing last September. I don’t mean to sound critical of the Mullen heirs – Peter’s artifacts was theirs to deal with as they pleased – but their story illustrates how collections seldom remain intact over multiple generations.

I wonder if the (Magnificent) Andersons toned down post WW I vehicles were a reflection/reaction of that period in time. While here we know of the ‘ roaring twenties ‘ and little else, in Europe they were still smarting and trying to understand the repercussions of mechanized war and. Perhaps more restrained on their part for that reason, a bit of Dada. Who’s to say?

Good points, Paul. Like the play on the “Magnificent Ambersons.”

Interesting story, Andrew, and thanks. Refreshing break from SBC 350s.

Isabel’s work on progressive causes like prison reform and higher education for the distaff rare in today’s me-generation arbitrage coin. Investment bankers’ Veyrons, Enzos, et al are not remotely the same dynamic as what the Andersons accrued.

You know how they say the first car race occurred immediately after the second car was made… I imagine the first car collector occurred immediately after the second model was made.

Let me correct your history to note that the first correction to history was made as the first collector allowed the first tour of that collection. And, the first concours judge took off two points for authenticity!

Living and growing up just across the other side of the Jamaica Pond, I have many wonderful memories of sledding on the hill and playing at Larz Anderson Estate. Later as a teen driving and ‘parking’ up there to watch the Boston Fireworks on the 4th, with a girlfriend of course. Finally I have a chair from the Larz Anderson home currently in my bedroom.. gifted from my Mom via her friend a maid for the Andersons……

Maybe the source is wrong, but “Isabel returned to Washington to find Americans suffering from an influenza epidemic and volunteered to assist those in need. Her contributions as a nurse resulted in being awarded the American Red Cross Service Medal, the French Croix de Guerre with bronze star, and the Medal of Elisabeth of Belgium”

Keep in mind she was of the “idle rich” of that era so a type not always portrayed in a good light. Not sure many went to serve as nurses. Not sure too many of our current wealthy people would today.

I went to the museum 8 years ago (still get email newsletters) and was impressed with the cars. Loved the “No Hill can stop me” car, my wife still talks about that one. It is absolutely worth going to, and I will again some day just to see the same old cars as they were. The carriage house is amazing too, and they do “other” car displays on a rotating basis upstairs. It’s a well-run thing.

However, the deepest impression made on me that day and the thing that crosses my mind more often is Isabel and the interesting life she chose.

Amen, Snailish.

Nicely put together. While they were early collectors for sure, there are a couple of other initiatives worth keeping in mind:

– in 1907 Leon Auscher organised an exhibition at the 10th Paris Auto Show which featured dozens of motorcars produced from the 1870s. This event received widespread media coverage in the European and American motoring press. It led to the establishment of the Musée national de la voiture et du tourisme (National Museum of Vehicle and Tourism) in Compiegne in the early 1920s.

– in 1912 the first known automotive museum was opened in London by the editors of Motor magazine. It lasted only two years.

– and obviously there’s the Montagu family, which kept all their cars over the decades and opened their carriage house to visitors in 1959. This was the precursor to the National Motor Museum at Beaulieu, UK today.

– Daimler, producer of the Mercedes cars (from 1926 Mercedes-Benz) had a history room as early as 1911. Their was first in-house museum was opened cca 1923. Then in 1936 Mercedes-Benz opened a museum for visitors.

I wrote a thesis on the history of curatorship, here’s the link:

https://hdl.handle.net/2381/43055

Your thesis is fascinating regarding the history of automotive curatorship in Germany and Austria.

Windshield wipers were invented by a lady named Anderson. The company name was Anderson Company, shortened to the name Anco, which is a brand of windshield wipers. Could this be the same Anderson as Isabel ?

No, that was Mary Andersen of Alabama.

is this Alex Pont of Surrey?

It is quite interesting to see this collection of Pre World War II cars.

For those who find this article interesting you will probably enjoy the story of Florence ‘ Pancho ‘ Barnes as well if not more so. Born into a life of privilege like Isabel, she chose a very different path. There’s an excellent documentary called ‘ The Legend of Pancho Barnes and the Happy Bottom Riding Club’ that’s well worth watching.

Fascinating story!

Toured it. Nice Carriage House. Staff was not friendly. Maybe it’s a Boston thing.

The museum is in Brookline….being unfriendly is not a “Boston thing”. Brookline is snootier!

When I saw the title, “Did this couple invent car collecting?”, I instantly thought Larz Andersen Museum.

I’ve visited the museum for the last 30 years, several times a year.

My next question. “Did this couple invent what has become the modern RV?”

I had the very same . As a young Bostonian gearhead, I regularly attended the great annual antique car shows held at “Larz” by the Bay State Antique Auto Club during the 70s. Those were the days before the start of the classic muscle car craze. The exhibit field was largely Ford A’s and T’s surrounding the exalted royalty of classic Packards, Deusenbergs, Cadillacs, Cords, Rolls Royce, Auburns, Cords, Franklins and on and on and on (please note that the above list is VERY far from comprehensive).

One unmentioned but fascinating sidelight to the story is that “Larz” had on display in the carriage house basement level a beautiful Ferrari 275 GTO said to have been (IIRC) a Le Mans winner associated with the great Phil Hill. I remember the extensive media coverage devoted to the museum’s reluctant decision to sell the car in order to keep the museum financially afloat. No idea how or why this car came into the possession of “Larz” in the first place, but I’d bet it must be an interesting story.

B

How about an article about the guy who invented ‘flipping’?

I would like to flip him off.

Many ‘collections’ are unintentional: just park the old car out back after buying a new one. After a few decades, there is the collection (of mostly rusted hulks) unless stored in a shed or barn.

“the mansion, after some years of disrepair of vandalism, was torn down in the 1950s” This is so sad! Look at the mansions, castles that have been kept and maintained in Europe. It’s good that the cars have been kept and are shown even if not maintained in running condition.