Media | Articles

Delightfully odd: 4 of America’s favorite French collector cars

Recently, French carmaker and Renault performance brand Alpine (pronounced Al-peen for all you non-French speakers) announced plans to sell cars in America. They’re not headed here till 2027 or ’28, though, and with just a pair of (yawn) electric crossovers and, maybe, an electric version of their acclaimed A110 sports car. This got us thinking about the French cars that are already here, and what the market is like. After all, it’s been some time since Americans were able to buy a new French car.

French cars in America

The French were automotive pioneers, and led the world in motorcar production and adoption at the end of the nineteenth century. At the height of Art Deco in the ’30s, many of the world’s most glamorous cars and some of the most prolific coachbuilders hailed from there. Today, France is the third biggest carmaker by production in Europe, and in much of the EU, South America, and Africa, you can’t walk a few blocks without banging your shins on something four-wheeled and French.

Yet they’ve never done well in the good ol’ U.S. of A. Beverly Hills Bugatti dealership aside, fabriqué en France just isn’t a label we see on our cars. In fact, the last time we average hot dog-eating, coach-flying Americans could buy a French automobile was before the Peugeot 505 quietly bid us adieu in 1991. That’s before many of today’s car enthusiasts were even born. There was a time, though, when we could easily buy cars from our oldest allies.

In the 1950s and ’60s, with America riding the post-WWII money train, selling cars here was a lifeline for many a European automaker. French brands were no exception, with Renault and Peugeot making the strongest plays to the American market.

In the end though, part of what doomed French carmakers in the US is what so many other European companies struggle with in this very large country—poor dealer support, inconsistent parts availability, and iffy reliability of systems that are unfamiliar to American mechanics. But there was another issue that’s a little more, well, French.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

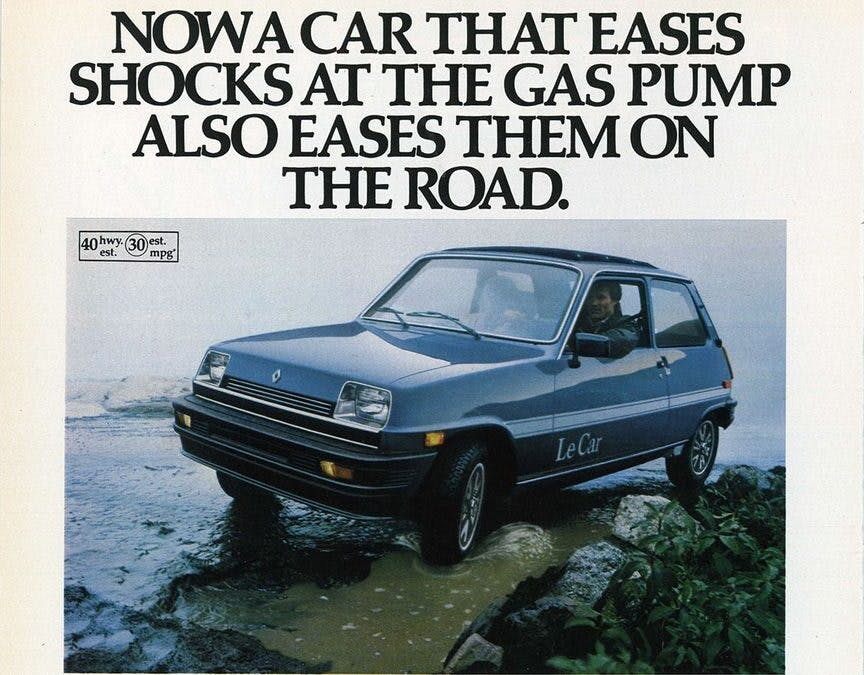

If there’s one stereotype about French cars (other than that they break a lot), it’s that they’re… odd. For all our love of individualism, Americans don’t tend to buy quirky cars. With very few exceptions (like the Renault Floride/Caravelle), the French didn’t design cars for Americans. They designed them for French people. As Eisenhower’s America built the Interstates, De Gaulle’s France traversed rougher, more pastoral roads. Cars suited to one weren’t particularly suited to the other. The Volkswagen Beetle, which at least had the Autobahn as a reference, simply won more American small car buyers in the ’50s and ’60s. So did the Japanese in the ’70s and ’80s.

These days, French cars on American lots are a distant memory, and enthusiast circles around the classic ones are relatively tiny. The most popular French car insured by Hagerty members is the Citroën 2CV, but among all classics, the snail-shaped Citroën ranks a lowly 469th, just behind the Ford Pinto. As for the rest of the most popular French cars in the market, they aren’t the ones that originally sold here in the highest quantity. They’re the cars people have saved, restored, or imported, cars that US enthusiasts value for their design, pedigree, character, and, ironically, their French-ness. Interestingly enough, most of them are Citroëns.

Citroën 2CV

Perhaps the most “French” of French automobiles as well as the most “designed for France, not America” car has got to be the Citroën 2CV. The brainchild of company vice president Pierre Boulanger, the 2CV (or deux chevaux, referring to the car’s tax class of 2 steam horsepower) was conceived in the 1930s to liberate the French countryside, where most people still relied on the kind of horsepower that has four legs and runs on grain.

Famously designed to “carry a basket of eggs across a plowed field,” the 2CV finally debuted in 1948 with a tiny, motorcycle-inspired air-cooled flat-twin, mounted in front of the front wheels it drove. Inboard front brakes, rack-and-pinion steering, radial tires, and interlinked horizontal coil spring suspension were all advanced stuff, especially for a cheap people’s car.

As for the weird bits, the side windows flip up like in a small airplane rather than roll down like in, you know, a car. The rear seat (and on certain models the radio) can also be removed, so you can have more luggage space or room to carry the trappings for a wine and cheese picnic. The shifter for the four-speed gearbox, meanwhile, sticks straight out of the dash and curves upward into a knob. It looks a little foreign, but if you ignore the layout and shift it like a regular four-on-the-floor, it doesn’t take long to get used to. Jokingly referred to as “umbrellas on wheels,” 2CVs also feature a full-width roll-back roof to open up part of or the whole car on sunny days, or to make room for tall cargo.

The 2CV chugged along for 42 years, with 3.8M units churned out by the time production ended in 1990. It gradually got better and more “powerful” over time, but it didn’t change a whole lot in those four decades. About 30 hp is the most 2CV drivers ever had to work with, so driving flat out merely means using all the engine’s resources to get to the posted limit. Despite constantly having to lean into the throttle, the little flat-twin is unburstable, and even at speed, a softly-sprung Deux Chevaux is as comfortable as most proper luxury cars, if not as quiet. In fact, the only real enemy of a 2CV is rust. Otherwise, simplicity and ease of service are baked in.

Buying and owning a 2CV should be a rewarding experience. Parts are affordable, working on one is straightforward, and the purchase price offers tons of fun and character for the money even if it’s a ripoff in terms of performance per dollar. The median condition #2 (Excellent) value for a 2CV in the Hagerty Price Guide is $29,000 and has doubled over the past 10 years. While not cheap, it’s less expensive than a Beetle of the same era. Driver-quality cars can be had for under $20K. Rarer variants like the two-tone Charleston model or the ultra-rare twin-engined 2CV Sahara can be significantly more expensive.

Citroën DS

An entirely different automobile from the same company and era is the Citroën DS. If the 2CV was for the French peasantry, the DS was for the French of the Space Age future. The star of the 1955 Paris Motor Show, it showcased the self-leveling, adjustable height hydro-pneumatic suspension that became a Citroën hallmark.

The four-cylinder engine was just about the only conventional thing on the car. Like the suspension, the semi-automatic transmission was also hydraulic, the single-spoke steering wheel looked like science fiction, the roof was fiberglass, the disc brakes were mounted inboard, the front track was wider than the rear, the rear signals sat high on the C-pillars, the brakes came on via a rubber button in the footwell rather than a pedal, and the headlights turned with the steering wheel. Citroën packed every bit of tech they could think of into the DS, which explains one of the advertising slogans: “It takes a special person to drive a special car.”

So special, in fact, other companies never really tried to copy it. In retrospect, that’s odd, since the DS is said to be among the most comfortable cars ever made. The hydropneumatic suspension even helped French President Charles de Gaulle escape an assassination attempt when the chauffeur skidded his DS to safety despite the four shot-out tires.

During its 20-year production run, the DS morphed from DS19 (1.9-liter) to DS20 (2.0-liter) to DS21 (2.1-liter) to DS23 (2.3-liter). It was also available as a lower-cost “ID” model with fewer convenience and power features as well as an extra-luxury “Pallas” model. Facelifts occurred in 1962 and ’67, and body styles in addition to the standard sedan included a “Safari” station wagon and a very rare, very expensive two-door convertible built by coachbuilder Henri Chapron.

Production worldwide totaled nearly 1.5 million units, but fewer than 40,000 were sold stateside from 1956–72. Expensive, slow, unusual-looking, poorly-equipped compared to domestic luxury cars, and riding on alien hydraulics, it just didn’t appeal to the American upscale car buyer.

Today, the median condition #2 value for a DS (not including the Chapron cabriolets, which cost well into six figures) is $43,100. Wagons tend to sell for less than sedans and prices can vary by year and equipment, but more important than anything is condition. They don’t carry DS parts at Pep Boys and there isn’t a Citroën specialist in every town.

Citroën SM

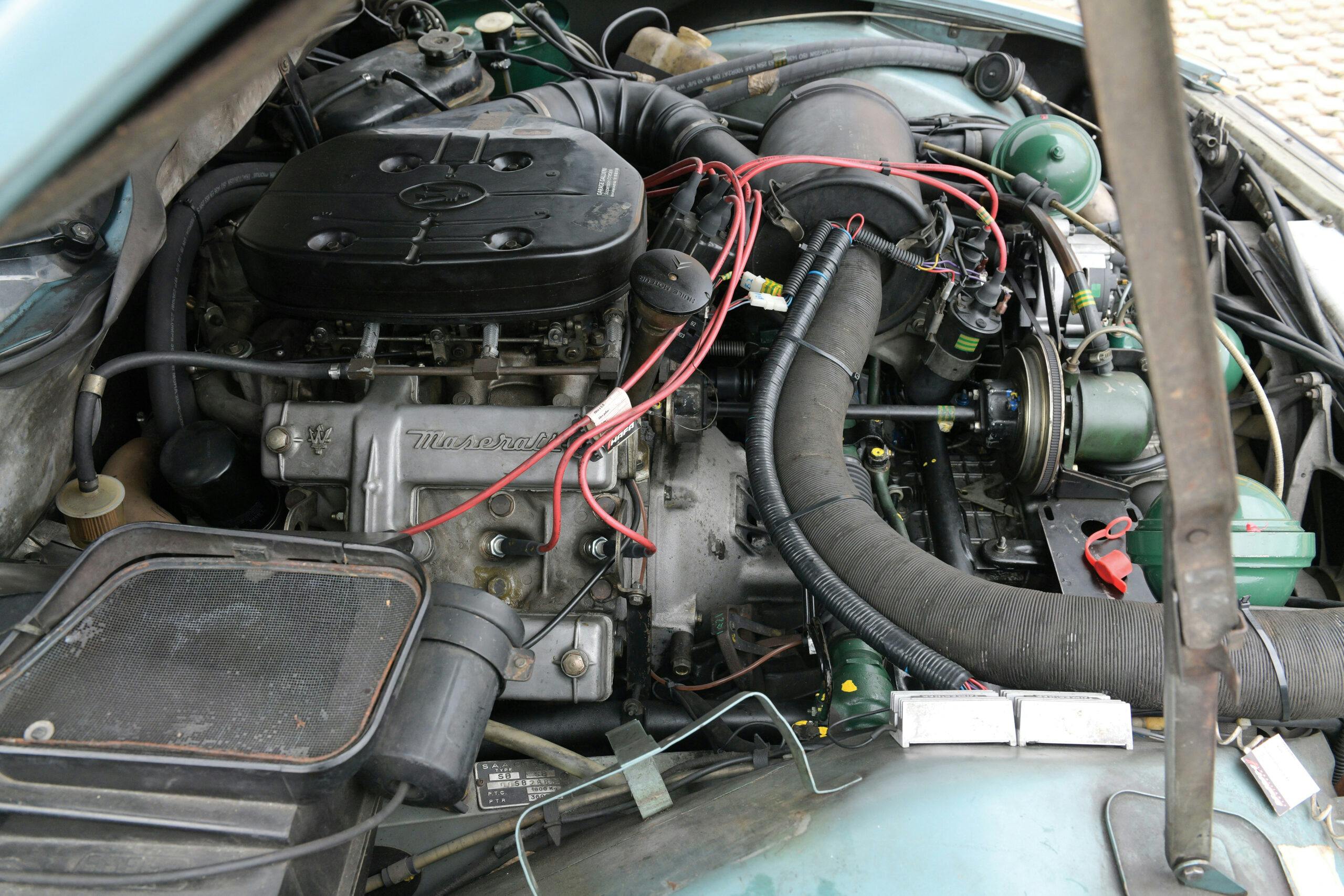

In 1968 Citroën, seeking a high-performance engine, bought a little company called Maserati. Now armed with their subsidiary’s four-cam V-6 (later used in the Merak), they stuffed it into the latest Citroën four-seat GT car, the SM. Building on the DS’s novel features but wrapped in a sleeker, more powerful, two-door package, the SM was the fastest front-wheel drive car in the world when it was new. It also featured cutting-edge stuff like variable-ratio power steering and rain-sensing wipers (in 1970!). Robert Opron, an architect by training, was Citroën’s head designer and gets the credit for the SM’s gorgeous teardrop shape. Produced for six years, the SM featured one of three engines: a 2.7-liter, Weber-carbureted version of the Maserati engine; a Bosch fuel-injected version of the same displacement; or a 3.0-liter unit. A 5-speed manual with a lovely open barrel gated shifter or a 3-speed automatic were the transmission choices.

Already reasonably well-established in the US, Citroën brought the SM to the States, where it competed with cars like the BMW 3.0 CS, along with the two-door personal luxury offerings from Detroit. Motor Trend gushed about the SM and awarded it Car of the Year (it was the first foreign car to win), which helped push US sales to about 2000 units out of the fewer than 13,000 sold worldwide. Regulations pushed Citroën out of the US in 1974. The same year, the company went bankrupt and ran into the arms of Peugeot. The SM was axed, while Maserati was sold off to DeTomaso.

Clean SMs do fetch a premium, but their cost of entry isn’t exceedingly expensive, especially given the rarity, beauty, and unique driving experience. Perfect condition #1 (Concours) values crested $100K during the pandemic boom, but they have since softened a bit and solid, drivable examples sell in the mid-five-figure territory.

Where the car can get expensive is in the cost of ownership. SMs come with all the complications of a DS and layer on an Italian thoroughbred engine that can be needy. European market cars tend to command a premium because they got the trick turning headlights (the ones over here were conventional fixed units) and five-speeds are naturally more sought after, but the most important things are condition and regular service.

Alpine A110

Coming full circle to Alpine, the original A110 is the car for which the brand is most famous. Market interest points to the little rally champ as one of the most sought-after French classics here. Though it never sold here in large numbers, its pedigree has cultivated a strong (if small) following.

America wasn’t on Jean Rédélé’s radar when he started Société Anonyme des Automobiles Alpine in the 1950s. The small Normandy-based outfit was primarily interested in racing, and after raiding the Renault parts bin to build a few sports cars, Alpine struck a breakout hit in the 1963 A110. With a fiberglass body on top of a backbone chassis (not unlike a Lotus Elan) and a rear-engine, rear-biased layout with snappy handling (not unlike a Porsche 911), it quickly became a rally favorite. Its short wheelbase, low height (44 inches), light curb weight (about as much as a Mini), and ability to sail around tight corners in a controlled slide brought quick success. The A110’s Renault-based, Gordini-tuned engines got larger and more powerful over the years, and enabled the car to win half of the top-level international rallies on the 1971 schedule, embarrassing the new Porsche 914/6 GT with a victory at the Monte Carlo Rally on the way. In 1973, the A110’s basic design was a decade old, but that didn’t stop it from winning the first World Rally Championship (WRC) title and six of the season’s 13 rounds.

The A110 was very much a car for European roads and drivers, but racing success spreads reputations worldwide, and Alpines are among the most desirable French cars in America. They’re expensive for a tiny four-cylinder car, but compared to a certain other classic rear-engined, lightweight coupe with lively handling and racing pedigree (ahem, 911), it’s not so bad.

Pricing A110s can be tricky. Condition #2 values range from $129K to $200K, but that doesn’t tell the whole story. Generally, later cars with larger engines are more desirable. Displacement included 956, 1100, 1300, and 1500cc versions. Later, faster ones used an aluminum 1600-cc engine, which is sometimes transplanted into earlier cars. Competition history, meanwhile, can make a bigger difference than anything. An ex-Works rally winner is going to sell for far more than even the world’s cleanest road car.

Then there’s another wrinkle: contract-built cars. Since demand for its rally-winning A110 outstripped Alpine’s capacity, it contracted out construction to firms in Spain, Brazil, Mexico, and even Bulgaria. Diesel Nacional (DINA) in Mexico built a few hundred and badged them “Dinalpins,” while Bulgarian company ETO built a handful of “Bulgaralpines.”

Most of the foreign-built A110s (about 1500) came from Fabricación de Automóviles Sociedad Anónima de Valladolid (FASA) in Spain. These foreign-built Alpines are rarer and mechanically identical, but typically sell at a significant discount compared to their home-grown siblings. If you don’t mind an “hecho en México” sticker, it’s the frugal way to get into one of the most popular French designs out there.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

I bought my first car in 1967, a lightly used 1965 Simca 1000, while still in high-school. Later it became my college transport. Plain, boxy and slow, but lots of interior and trunk (frunk?) space for such a small car. Great in the snow.

I had next-to-zero mechanical problems with it. Back then, Simca 1000s where imported and sold in the U.S. through Plymouth-Chrysler dealers and tune-up, etc. parts where pretty easy to get.

The little thing sounded mean after I splurged on an Abarth performance exhaust system with the twin chrome tips out the back! And with the pair of Lucas Flame-Throwers I added to the front, in my teenage mind I imagined myself ready for the next Monte Carlo Rally.

I have had a lifelong love affair with French cars ( and the women that came with them).

If you were from another planet and only had a description of what a human looked like and then tasked with designing a mode of personal transportation, It would probably look a lot like a French car. Hopefully a 2CV, more giggles per Km than any car ever made

I spent time in France in the 1980’s. They had a Peugeot 505 station wagon and a pickup (like a little El Camino). They looked great and could be had with diesels and manual transmissions. I tried to find either here in the states and couldn’t. I would still consider buying either if I could find one in California with a current title that could pass our stringent smog requirements.

I recall seeing DSs as a kid in middle school in the late 60s and early 70s. Always thought they were weird – and ugly. Then one day I saw a DM. I thought it was a ‘new DS’. I was blown away. Still am. It is lovely. I don’t think I could ever come to grips with owning or driving one, but my they are pretty!

After a succession of Minis, I bought a 2CV new in the UK in 1979. It was GBP 2200 at a time when a basic Mini City was GBP 3300. Did the usual run down to the Mediterranean coast and back in great comfort, if not great speed. Loved that car, unfortunately couldn’t take it with us when we emigrated to Canada shortly thereafter. I think it’s too late to get a decent 2CV at a reasonable price now…….

Didn’t realize we had a favorite French car. Drove a Dauphine once. The wire winding in the generator came apart and stopped the car cold in its tracks.

Can’t forget Columbo’s car – a 1959 Peugeot 403 (there were several used, I think one was a ’60). While not making Peugeots look particularly good, it was a great fit for Peter Faulk’s character and a central theme in the series.

Renault Caravelle Convertible! It was the summer of 1964 and I had just turned 16 when friends of my folks asked me if I would like to drive their maroon Caravelle Convertible during the summer. They were going on vacation and wanted someone to take care of it. It opened my eyes to convertibles, power to weight and handling, and sports cars. That was probably the best summer I have ever had. It was a chick magnet, and I went on rallies, cruising the main and picnics in the countryside with the top down. My buds with their Chevies, Fords, Pontiacs, and Olds couldn’t believe it. It was a sad day when I had to give it back, but I became the owner of a 1962 Buick Skylark two months later, with the 215 V8. It started a journey and love of 2 seaters which is still present today. Viva la Caravelle!

The only ones I’d be interested in are the DS and the SM. Unfortunately, having worked on a couple of SM’s in the past, you really have to be in to SM to put up with the, uh……”differentness” of them.

What, No Panhards ? 2 cyl , front drive, air cooled, ugly. I’ve got a Panhard motor out in the garage, hasn’t been run in years but it sounded like a Harley the last time it ran.

By far, the worst car I ever owned was a Renault Dauphine. I was working my way in college (yes you could actually do that in those days) and thought I was upgrading from a 56 Norton. It caught fire regularly and I even had a blanket just to smother the frequent fire evidenced by the big black burn spot on the engine compartment lid. The right rear brake was the only one that worked, making stopping in the rain interesting. I think I sold it for $25 taking a big loss for a starving student.

I forgot to tell you that I had paid 50 bucks for it.

I am the proud owner of a 1972 Citroen DS 21 Pallas. This is my second Citroen; the first being a brand new 1970 DS Special (Special meaning it was a citron (lemon). I had to do a lot of soul searching before I decided to buy another one; even friends said to me “don’t you remember how much money you poured into your last one?” Anyway 18 years later and I have no regrets. I am fortunate enough to have 2 mechanics in my area and parts are pretty easy to come by. It is like riding on a cloud and a definite head turner, not to mention a real chick magnet if you’re looking for older French women.

Fun Fact: Although primarily considered a “German” car and sold in the USA via Buick Dealers did you know the bodies for the Opel GT (1968-1973) were actually built in France? Debuted as a styling exercise in 1965 at the Paris and Frankfurt motor shows (and the design process had started in 1961 …not copied from the 1968 Corvette as some claim according to documentation at the Opel Museum) the body & interior were made at French contractor Brissonneau & Lotz and then shipped to Germany where drive train & suspension were installed. So, in a way, the Opel GT could be included as one of these quirky French cars?

The 68 corvette is a direct rip off of a 64 Pontiac Bashee

And the Banshi was a ripoff of the Opel design from 1961. Not really surprising when you know that GM ownwed a controling interest in Opel from 1929 until 2017. Of intrest : Read up on GM’s “Project Opel”.

I worked at a Citroen, Peugeot Dealer in Salt Lake City and owned an early 504 diesel. Citroen had a tuff time with the US bumper laws yet the frame was designed to collapse slowly protecting the driver. We had one costumer that crashed and rolled his SM. The car was destroyed yet he walked away. He came back and bought another SM. Yes the cars are quirky but beautifully designed and far ahead technologically.

A 2CV is virtually impossible to roll going forward at any speed. Has to do with weight distribution and the advanced suspension. I one saw a video of a DS with one of the rear wheel removed drive away. Again, advanced suspension and hydraulics.

I was sorry to see no mention of Renault’s 4CV. Looking like a 2/3 scale 46 Chevy on the outside, but when compared to other 1946 cars, it was a very advanced design underneath the sheet metal. My first car was a ’59 4CV, purchased for $300 in 1963 while I was in college. It became my daily driver for 15 years, racking up 137000 miles and adventures in 24 US states (including crossing Kenosha Pass in the Rockies at 10000 feet), and another 9 states in Mexico. It was a great way to learn how to work on cars (which I did fairly often!), but it never left me stranded on the road. I averaged over 35 mpg for that 137k miles, autocrossed it (21 first place trophies)–and it’s still in my garage!

The Dauphine was based on the 4CV’s design, just slightly lengthened with updated styling but nearly identical mechanicals. Oddly enough, stuff that broke regularly on a Dauphine were also used on 4CVs–and hardly ever broke on the 4CV. Oh, and Alpine got its start building sporty bodies using 4CV floorpans and running gear.

In college, I made summer spending money by buying inoperative 4CVs, fixing and painting ’em and then selling ’em before I returned to school. Beat flipping hamburgers. Over the years I’ve owned 13, and still have an all original (4700 miles) ’48, a one-of-one US spec ’56 convertible…and the one that started my love affair with ’em, the ’59.