Media | Articles

Certified: Is restoring your Ferrari at a factory shop worth it?

The Ferrari Classiche restoration workshop is housed in a foundry in Maranello, one of the brand’s original 1947 factory structures. “A Ferrari, to come back into the factory, it must be a real factory,” says Luigino “Gigi” Barp, a 33-year marque veteran and the Classiche director, as he opens the door to the industrial space.

Inside, vaulted skylights filter sun onto an array of vintage vehicles in various states of disassembly. A Boano-bodied 250 GT California prototype is just a shell, a reinterpretation of a puzzle box of parts. A barn-find red Daytona retains its moldering interior and filthy patina. A chassis-less cerulean Dino 246 is so shiny it appears ceramic. Poised nearby is a body-less 121 LM, its hulking DOHC straight-six exposed, one of forty racing Ferraris onsite. If Italy were ruled by pharaohs, this would be the pyramid in which they’d be entombed, and these the worldly conveyances intended to ferry them to the spirit realm.

Instead, these are customer cars, present either to be inspected and “certified” or to undergo a restoration. Since Classiche was founded in 2006, fewer than 150 cars have endured the latter process. “It takes fourteen months for a complete restoration,” says Barp. “And it can be more than a million euro for a special one-off, like a 212P [a champion, late-Sixties hill-climber]. But if you spend a million, and the car is worth ten million, it is nothing.”

One of Ferrari’s core contemporary values is charging whatever the market will bear for its desirable, limited-edition, appreciating products. But Classiche can command these extortionate prices for other reasons.

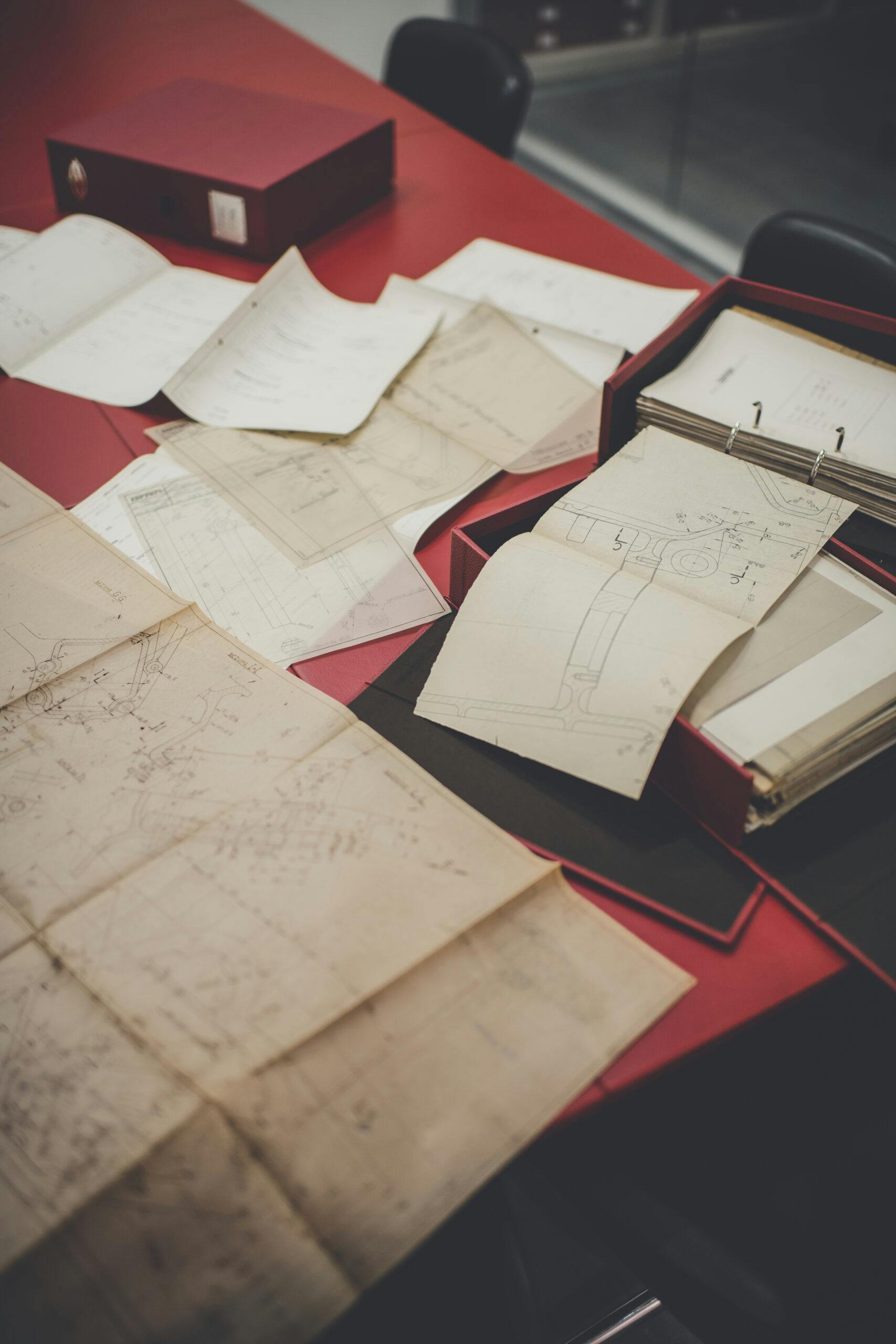

“This is the soul of Ferrari, the real soul,” Barp says as he leads us into the archive room. The space is crammed with rows of shelves, each containing scores of Rosso Corsa leather-bound binders. Each holds the build sheet for a specific car, ordered by a specific owner.

“We have one of these for every car built since car number two,” Barp says, selecting a random folio from the shelf. He pulls out an assembly data sheet for a customer order from 1951. It lists the engine number, the test bench results, the type of tires outfitted. “And, my mission, after 33 years with the company, is to keep these forever.” (Ferrari is in the process of digitizing its archives.)

This documentation gives Classiche the privilege, unavailable to other restoration shops, of officially sanctioning a vintage Ferrari—prior or subsequent to any restoration, onsite or elsewhere—as factory correct: proper chassis, body, paint, interior, engine, transmission, etc. And it allows it to confer upon the vehicle a certificate of authenticity, a shrunken version of the archive’s folios, a small “Red Book.” This document has thus become a commodity. “If you don’t have this,” Barp says, holding up a sample Red Book, “you don’t have the truth.”

If you spend a million, and the car is worth ten million, it is nothing.

—Luigino “Gigi” Barp, director, Ferrari Classiche

This dictum doesn’t seem to be shuttering notable Ferrari restorers. “Anybody who works on Ferraris for a living these days is busier than anything,” says Tom Yang, who runs a highly reputed Prancing Horse specialist shop in upstate New York. “There is plenty of work to go around.” But it is having an impact on the collectible car market, especially as other automakers have taken note. Aston Martin, BMW, Jaguar Land Rover, Lamborghini, Mercedes-Benz, and Porsche have poured significant resources into this arena and now offer restoration and certification of vintage vehicles.

“Pretty much everything we do is done in-house,” says Paul Spires, who runs Aston Martin Works, the brand’s restoration shop, housed at the marque’s historic factory in Newport Pagnell, England, where many classic David Brown–era Astons were built. Works has its own trim, body, chassis, and paint shops. It stocks millions of original parts, and it has the capacity to create rapid prototypes. It has 125 people working onsite, and a years-long waiting list.

Although just founded in 2015, Lamborghini’s PoloStorico factory restoration program has seen a similar expansion. “We are now running 21 projects, which is the highest of any year,” says Francesco Stevanin, who directs the subsidiary. “We had just 11 last year.”

As with Ferrari, these in-house projects are not inexpensive. Lamborghini charges €250,000 to €300,000 ($275,000 to $330,000) and Aston charging £425,000 ($545,000) plus tax.

The results in the marketplace have been notable. Spires, Stevanin, and Barp all claim that vehicles restored by their shops command a premium when sold. “The added value percentage, between a certified and an uncertified car, is between 15 and 16 percent, in the general market,” Stevanin says.

Independent assessment seems to back up these claims. “I think for many people, being able to say, not only was my car built by Mercedes-Benz, it was restored by Mercedes-Benz, is a big deal to them. It’s the manufacturer remanufacturing the same car and once again putting its stamp of approval on it. So it becomes more valuable,” says Dave Kinney, publisher of the Hagerty Price Guide. There are also instances where factories are doing surgery no one else can. “The only company really capable of repairing or restoring a badly damaged McLaren F1, for instance, is McLaren,” notes Hagerty’s resident automotive historian and concours judge Jonathan A. Stein. “However, there are several really fine independent shops capable of performing a painstakingly accurate restoration of the great marques,” he adds.

Noted British car collector and dealer Simon Kidston adds that factory restoration can offer something of a new lease on life for cars that otherwise carry asterisks. “For example, a Ferrari 250 LM that might have started life as a bit of chassis, that has now been through a factory restoration. That will be worth a lot more money than it would have been just as a ‘car’ with a big story attached.”

A Ferrari 250 LM that might have started life as a bit of chassis, that has now been through a factory restoration. That will be worth a lot more money than it would have been just as a ‘car’ with a big story attached.

—Simon Kidston, founder, Kidston SA

But, in general, experts like Kidston, Kinney, and Stein aren’t sold on factory jobs. They claim the workers are often less experienced than those in established restoration shops and are drawn from the world of new-car manufacturing. “Very talented 30-year-olds,” Kinney calls them.– They claim the factory may ignore changes or substitutions that were made at the original customer’s verbal request, or via production limitations—especially in an era of coachbuilt bodies—but not noted in the archives. “As-built can be different from as-designed,” says Kinney. (Barp underscores this issue. “The carrozzeria have very limited records. A little with Pininfarina. Vignale, very little. Frua, almost nothing.”)

They also claim the manufacturers tend toward over-restoration. “Sometimes, younger employees may not be as well versed in what is correct or not, and I have heard stories of undoubtedly original components on one-owner cars being identified as ‘incorrect’ and being replaced,” says Stein. Kidston, a preservation class judge at the Pebble Beach Concours, agrees. “If you look at it from a business perspective, you can make a lot more money tearing something apart and replacing it with all new parts than you can saying to an owner, ‘Actually, I think you’re better off not touching it, not interfering with surfaces and finishes that may be 30, 40, 50 years old.’ ”

And, most of all, they balk at the price of factory restorations, which amount, in Kidston’s words, to “a tax on the profit of collectors who have done well out of owning their cars.” He adds, “If you want perfection, just dropping your car at the manufacturer and saying, ‘Call me when it’s ready and tell me how much I owe you,’ is definitely not the right approach. You’ll be waiting for a long time, you’ll be severely out of pocket, and your car will be picked apart the first time it gets scrutinized by judges who actually know what they’re looking at.”

Do they know what they’re paying for at Classiche? What difference does it make? They get invited to a Ferrari dinner when they finish. They get to be on the list.

—Tom Yang, Ferrari restorer

Of course, Barp might point to his binders as evidence that Ferrari knows more about Ferraris than a concours judge. Perfection—even perfection costing millions of dollars—is subjective. Ferrari and other OEMs are, in any event, interested in more than best of show trophies. As with their efforts in clothing, accessories, and real estate, they are seeking new opportunities to provide consumers with brand access, key for today’s seekers of “experiential luxury” and another means to keep customers within their orbit. “We know with Ferrari customers, they are enamored with the branding of Ferrari,” says Yang. “Do they know what they’re paying for at Classiche? What difference does it make? They get invited to a Ferrari dinner when they finish. They get to be on the list. And if that’s what it costs, and that’s what they have to do, then they do it.”

Ferrari is already inventing ways to keep clients beholden to the factory long after their Classiche restoration is complete. The brand recently began distributing a new “Passport” with each Classiche inspection or restoration. “When you receive it, you get your first stamp,” says Barp, holding up the little red booklet. “After that, you have to go every two years to get the car recertified.” There are 72 official Ferrari recertification inspection stations throughout the world. If you don’t pass, you can guess where the car is recommended to go for remediation.

__

NYC-based Brett Berk writes about the intersection of cars and culture for Architectural Digest, GQ, Wired, Vanity Fair, and many other outlets.

***

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.