Media | Articles

Buying my first Porsche and everything after, part 1

When I was a kid, the bubbly shape of my father’s Porsche 356s made me fall in love with cars. So, too, did the high, happy engine melody and the wind rushing through my hair as I sat on the Speedster’s precarious rear seats (sans seat belts, of course—this was the late ’70s after all). Porsche was a sacred part of my childhood that scored a mark on my heart, but life happened and I never thought I’d be in a position to buy one of my own.

An ember in the form of a neighbor’s 1965 Togo Brown 356C Coupe kept my hopes faintly alive for fourteen years as I passed it almost daily in our apartment’s communal parking garage. It was rough around the edges and it didn’t run, but I never stopped pining for that car.

My Porsche dream reignited after I made a pivot to become an automotive journalist. My resolve growing stronger, I even convinced her to let me to pull it out into the light for a wash. No matter how many times I asked about buying it, though, she demurred. I looked up its value in the Hagerty Price Guide and offered her what I thought would be a fair price considering the work it needed but, in her mind, it should have been worth tens of thousands more. And it would be, if it ran. But a clean 356 isn’t cheap, and values have shot up over 50% from the mid-2010s to today. There was no way I could afford that.

So, I did what a lot of buyers do after getting priced out of their dream car – I looked for alternatives. The 356s spoke to me, sure, but I always loved the look of the early 911s, too. I also knew that the 912 combined the 911 platform with smaller four-cylinder engine of the 356. Just like when it came out in 1965, the 912 offers a more affordable alternative. When I started checking out prices, I saw two interesting things: First, 912 values had recently risen, but not to astronomical heights. Second, I noticed that the bump in 912 prices seemed to have pushed up 911 prices of the same vintage. Or maybe it was the other way around. As those early 911s became more unattainable, the 912s caught the attention of interested buyers like me. Either way, emboldened with this knowledge, I was determined to strike quickly.

I made the mistake of setting notifications from auction websites for 912s. It didn’t take many dings in my email inbox to see that 912s started coming up for sale fast and furious, and with each increasing sold price or “reserve not met” notification it seemed prudent to get on with it if this was something I genuinely wanted.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

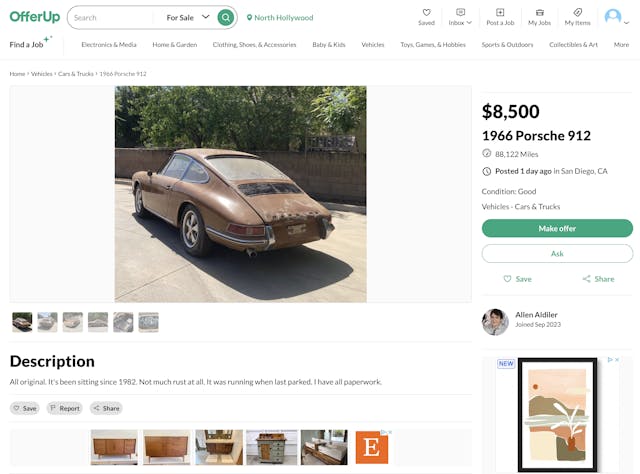

That urgency sent me to OfferUp, an online marketplace similar to Facebook Marketplace or Craigslist, but a lesser-known one. A good friend, who also happened to be a 912 owner, had found some great deals there. My initial search bore little fruit, but I was determined and kept at it until one popped up. It looked incredibly promising. Or, I should say, too good to be true. Sometimes people want to believe something so badly they’ll ignore red flags and reason. Scammers pray on that kind of emotion, and I got hooked. The bait in this case was a 1966 Porsche 912, advertised as a minor project and asking $8500.

After a morning of frenzied back and forth texts with the “seller” (which is a no-no, never give scammers your phone number), I made my way from Los Angeles to San Diego to meet the 912. I’d consulted with several friends, the kind of people who buy cars online as frequently as most people buy groceries, and even they didn’t know for sure if this Porsche was real or not.

I’d spoken to the seller on the phone, but that’s not unusual. He had a California phone number, but that’s easy to fake. The brand-new seller profile and an odd, unsearchable name were two more red flags, and then there was this seller’s demand for a deposit.

Initially, he wanted a $1000 deposit as “more people were interested in the car.” Another no-no. Deposits are a bad sign. Thankfully, at this point my spidey sense finally started tingling. A grand is a big ask. I wasn’t willing to lose that much. I guess it didn’t tingle quite enough, though, because I was motivated and kept going. After a bit of back and forth, we agreed on $200. That was a sum I was willing to part with, and I had to see if there was indeed a Porsche 912 behind door number one.

(Helpful tip: If you do send money to anyone use PayPal. They are the only service that guarantees your money if you get scammed. With Venmo, Zelle, Cash App or others you have no recourse if you’re taken for a ride.)

It wasn’t until halfway to San Diego when a friend, who had come along for the ride, did what I should have done long before getting into this mess. One reverse image search later, we confirmed that the photos I’d been looking at weren’t for a 912 for sale in San Diego. They were actually from an East Coast dealer selling their 912 for $34,000. Tail between my legs, I bought my friend dinner and swore off Porsche shopping.

For about two days.

Another listing popped up, this one on Craigslist. It was a project. The silver paint looked sun-faded, almost like bare metal. There was no indication it ran and not much additional information, but one of my 912 consultants thought it might have promise. If it was a real car, of course. More importantly, the price was $20,000 less than cars I’d seen that were only slightly better-sorted. That would leave room for unexpected repairs.

Too good to be true again? Understandably, I felt hesitant. Fool me twice…as they say.

I contacted the seller, who immediately suggested I come see the car that afternoon. No deposit necessary. I went, and the seller gave me privacy as I inspected the car, including one of my trusty advisors over FaceTime. I didn’t feel pressured. The seller answered any questions he could, hadn’t done anything with the car since he bought it, and didn’t know much about it. He didn’t even know if it ran.

Another red flag? Who buys a car and never tries to start it?

Though it sat in a dirt lot behind a sun-beaten house in the San Fernando Valley—the LA suburb where all automotive rubber goes to die—there were many good things about this 912. The dash was brand new. The tires weren’t that old and held air once filled. The engine had all of its bits, and all of them moved, even if they were covered in spider webs. The crown jewel was that it had a brand-new floor pan. That meant minimal rust repair. Someone before this owner, then, had quit partway through a restoration but had gotten far enough along to embolden me. With each bit of good news I visualized the bottom line to a drivable car shrinking. Still, I tempered my excitement.

When he showed me the title, it didn’t have his name on it. Gulp. How is that possible? He didn’t register it because it was non-operational, and he didn’t want to pay registration while he worked on it. Fair enough, and some of my Porsche friends had apparently done this before, too. This seller was also a real, Google-able person.

No, this wasn’t the 356 of my childhood dreams and it certainly needed a lot of work, but this 912 was attainable. The seller gave me a couple of hours to consider, but within 10 minutes of leaving I called him back and said yes. Bill of sale in hand, I wired the money, picked up the keys and title, then called a tow truck to come get the car. “Holy smokes, I own a Porsche,” I thought as I followed the flat bed home. Then reality descended. What the heck do I do now?

(Read part two of Lyn’s 912 story here.)

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Before you do ANYTHING ELSE, get the title in your name. If the title is not in the name of the person who sold it to you it can become interesting getting the past people to sign off on it and can take years. Good luck…

Your dive into bringing a classic back to life is excitting, looking forward to future stories on your restoration project. One question, I see a lift in your garage can you tell me what model it is?