Media | Articles

Gabriel Voisin and His Art Deco Tour de Force: 1935 Avions Voisin C25 Aérodyne

Gabriel Voisin (1880–1973) could be described as a 20th century industrial renaissance man, a man behind groundbreaking efforts in architecture, aviation, and automobiles. He designed some of the world’s first prefabricated homes, he challenged the Wright brothers for the claim to be the first to fly, and a car he designed and built beat Ettore Bugatti’s racers on the track.

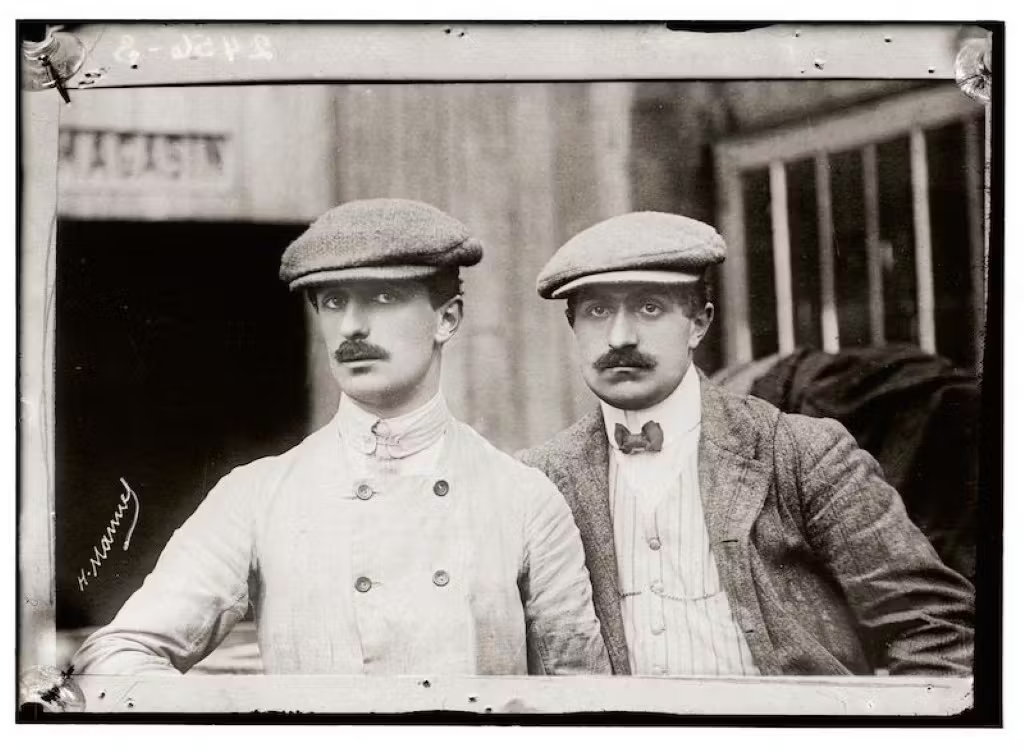

Though he trained and first worked as an architect, Voisin initially gained prominence in the nascent aviation industry. In 1905, he and his brother Charles founded the firm of Avions Voisin (Voisin Aircraft), and a year later they constructed their first airplane. In 1907, their plane was the first to take off under its own power, earning Gabriel Voisin entry into the French Legion of Honor. Voisin always claimed to be the first to fly a heavier-than-air aircraft. That was a point of pride with Voisin, as the Wright brothers’ famous Flyer’s takeoff in 1903 was assisted by gravity, with their airplane accelerating along a downhill track.

The conflict with the Wrights was not just over honors; the Voisins had to defend lawsuits by the Wrights alleging patent infringement. Despite the litigation, their business grew and by 1911 they had sold dozens of airplanes. Tragedy struck the family the following year, though, when Charles died in a motoring accident. His death is said to have deeply affected Gabriel. The company’s business, however, grew substantially when the French ministry of war selected the Voisin biplane as the fledgling French air force’s standard winged aircraft in the run-up to the First World War. The demand from the air force was so great that even though employment grew to 2000 employees over the duration of the war, other airplane manufacturers were contracted to build Voisin biplanes.

Following the war, much like Henry Leland did to convert Lincoln from the manufacturer of V-12 “Liberty” engines for the American military to the maker of luxury automobiles, Voisin turned his company from a maker of warplanes into one that built luxury cars.

Voisin’s first automobile, named the C1 to memorialize his brother Charles, was a licensed design based around an 80-horsepower sleeve-valve Knight engine that Citroën had passed on due to the expense of manufacture and paying Charles Knight his fees. Voisin, however, preferred the quiet and smooth-running Knight design and would use it for the rest of his career.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Every Voisin automobile that followed the C1 was a completely in-house design and featured aircraft-inspired instruments and electrical equipment; suspension geometries that were advanced for the day; the quiet and efficient sleeve-valve engines; interchangeable components, including precision castings; and unique—even radical—body designs.

Cyclecars were a big thing in the early 20th century, and Voisin dabbled in that market with the 500-cc “le Sulky.” At the Paris auto salon of 1921, Voisin displayed the firm’s first full-scale automobile of its own design, the C2. Today we would call it a concept vehicle ahead of its time: It had a narrow-angle 7.2-liter V-12 engine; hydraulic brakes with individual circuits for each wheel, which long predated the introduction of dual-circuit braking systems that preserve stopping power in the event of a hydraulic leak; and a clutch made up of two turbines facing each other in an oil bath, which is close to the description of the torque converter later used in automatic transmissions. Voisin himself acknowledged that the C2’s complexity made it “prohibitively expensive” to manufacture.

On the heels of the C2, Voisin’s second production car was the C3, with a high-compression 120-hp engine. Voisin offered a half-million franc prize to anyone who could make an engine of similar displacement that equaled his engine’s performance and fuel economy. There is no record of any competitor accepting the challenge.

The C3S of 1922 was a higher-performance version made for racing. It had a more powerful 140-hp engine that was underslung in the chassis to achieve a lower center of gravity for better handling. To cut through the wind, Voisin and his chief engineer, André Lefèbvre, gave the C3S a fuselage as narrow as possible, adding streamlined elongated running boards only to meet the minimum width requirement of the Automobile Club de France. Voisin entered four C3S cars in the Strasbourg Grand Prix, taking all three podium spots, as well as fifth place, against competition that included Bugattis, the most successful racing marque of the time.

Although he wasn’t a great businessman, losing control of the company twice, Voisin understood the value of promotion. And while he recoiled from the kind of emotional advertising American automakers used, he was not averse to publicity stunts. To that end, the four-cylinder C4 raced, and beat, the Orient Express train on its run from Paris to Milan.

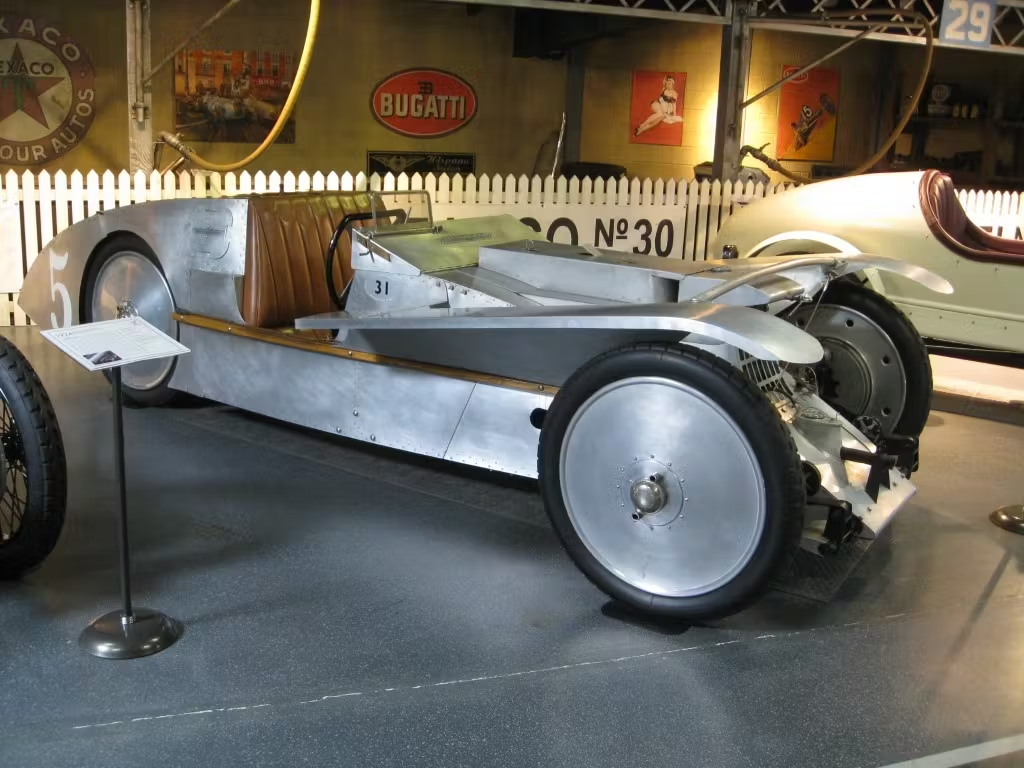

Voisin’s background in aviation was evident in the construction of his automobiles. He used aluminum and other lightweight metals extensively, and some assembly methods borrowed from aircraft manufacturing. The Voisin Laboratoire Grand Prix car of 1923 was one of the earliest automobiles to use a monocoque, or unibody, construction. Along with his designer, André Noël Telmont, Voisin was an adherent of “rational” coachwork that emphasized lightness, angular lines, central weight distribution, and low, underslung chassis. With his brother’s demise in mind, safety was also a concern.

While his background in aviation would lead us to believe that Voisin was a pioneering automotive aerodynamicist, and though his cars embraced the streamlined art deco design ethos of the era, Voisin was a personal friend of modernist architect Le Corbusier (who designed door handles for early Voisin vehicles), and architecture may have influenced his cars’ aesthetics more than the wind.

The Roaring Twenties were kind to Voisin. The company produced a series of four- and six-cylinder luxury cars, including the six-cylinder C14 introduced in 1928, which sold about 1800 units through 1932. As prestige brands around the world engaged in a “cylinder war,” Voisin also started to develop a modern V-12.

That powerplant appeared in 1929, when Voisin introduced the C18. The 4.9-liter sleeve-valve V-12 produced 113 horsepower, making it one of the most powerful production engines of the era, though the rest of the car was dated and sales were disappointing. The following year, the C20 debuted with the same engine, but with an elegant cabriolet body on an underslung chassis. By then, though, the Great Depression had begun and production of Voisin cars slowed to a trickle.

The C23, which would form the mechanical basis for a series of Voisin models, was introduced in 1930. It featured a 3.0-liter inline-six sleeve-valve engine, an in-house design that generated about 80 horsepower and was enough to propel the car to a top speed of approximately 120 km/h (72 mph). The C23 had driver-adjustable Dufaux-Repusseau shock absorbers, Vosin’s typical aircraft-inspired instrument panel with a surfeit of Jaeger gauges, and visually arresting art deco interior fabric. By Voisin standards it sold well, about 400 units. The 1932 Paris auto salon saw the reveal of the C24, essentially the C23 with an underslung chassis, with an engine tuned to deliver an additional 10 horsepower.

Unfortunately for Gabriel Voisin, 1932 was also the first time he lost control of the company to his financial backers—though he was able to reassert control in 1934, when the C25 model was introduced. The C25 added an electromagnetic preselector gearbox to the mechanical specifications.

A total of just 28 C25s were made, eight of them (some sources say six) were visually arresting Aérodyne models first introduced at the 1934 Paris salon. Gabriel Voisin called it “the car of the future.” A radical departure from the more conventionally styled earlier Voisins, the Aérodyne had a streamlined profile with flat sides, porthole windows in a pneumatically activated retractable hardtop roof, seating for five, and luxury appointments. At 88,000 francs, about $5800 in the U.S. dollars of the day, the C25 Aérodyne was close to the top of the market, about as expensive as a Cadillac V16 and approaching Rolls-Royce territory. That may explain why so few were made.

The C25 Aérodyne broke Voisin’s tradition of using motorcyle-style front fenders and instead featured aero-inspired wraparound fenders, low, faired-in headlamps, and skirted rear wheels. Two-tone paint schemes finished off the art deco aesthetics. And while the wraparound fenders were a departure for Voisin, the C25 did maintain the company’s traditional use of stabilizing aluminum brackets between the radiator shell and the headlamps. The tall, winged Voisin mascot remained as well.

Gabriel Voisin hoped the C25 Aérodyne would change his company’s fortunes, but that was not to be, and in 1937 he again lost financial control of the firm to aviation engine makers Gnome et Rhône. Gabriel Voisin stayed on as an employee during World War II and continued to work there doing research after the company was nationalized under the SNECMA aerospace corporation, until the factory was shuttered in 1958. In total, about 11,000 Avions Voisin automobiles were made.

Ironically, the most successful car that Gabriel Voisin designed was the Biscooter, which stood for “double scooter,” a minimalist microcar developed for a rebuilding Europe after the war. Introduced at the 1950 Salon du Cycle et de la Moto, it was powered by a crank-started single-cylinder engine driving just the right front wheel and had an unusual three-point cable-actuated braking system. The Biscooter had an all-aluminum body, a flat windshield, two lawn chair–looking seats, no doors, no metal roof, nor even a reverse gear (presumably it was light enough to be pushed back with a leg hanging out of the vehicle), but it was received well enough to generate more than 1000 orders.

Voisin’s bosses at SNECMA apparently thought the Biscooter was either too radical or too primitive and instead developed a more conventional small car, which greatly displeased Voisin. He ended up selling the rights to the design to the Spanish firm, Autonacional S.A., which developed a more enclosed body and introduced it as the Biscúter. Autonacional would go on to sell more than 12,000 Biscúters, which got nicknamed the Zapatilla, or little shoe, by the public. Voisin would continue to develop the Biscooter idea, designing three-, four-, and even single-seat models.

Voisin finally retired in 1960 at the age of 80. Reportedly, he was prouder of his role as an aviation pioneer than as an automaker. When a visitor arrived at his home in Tournus at the wheel of a vintage Voisin car, its maker remarked, “Why are you bothering with old crocks like that?” Gabriel Voisin died on Christmas Day, 1973. He is buried in Le Villars, near his birthplace.

If the Avions Voisin C25 Aérodyne strikes your fancy, depending on the source, there are either three or four that still survive. One of those, chassis #50023 is being offered at Gooding & Co.’s Amelia Island auction next month. You had better bring a letter of credit, as it is estimated to gather somewhere between $2 million and $2.5 million when it crosses the auction block.

Are these beauties available anywhere foe viewing? If so, where?

Unfortunately, not anymore. Most of those pictures were taken at the Mullin Museum in Oxnard, California, which closed last year.

Very neat cars I knew nothing about. You can see the various influences on it.

I’d heard that it burns oil visibly due to the sleeve valve design. True?