Media | Articles

Toyota’s “Epic” powerboat failure didn’t help its reach toward the skies

In the late ’90s, Toyota was on a roll. Not only was the Camry sedan well on its way to outpacing the Ford Taurus as the best-selling car in America (a title it snagged for keeps in 2002), but the automaker was also riding the wave of its successfully-launched luxury brand. Lexus enjoyed considerable acclaim and more than a little profit from the outset at the beginning of the decade.

Flush with cash, Toyota went looking for new worlds to conquer. Having already achieved dominance on land, the Japanese automaker turned its eyes to the skies, churning out the twin-turbo FV2400-2TC V-8 aviation engine based on the 4.0-liter 1UZ unit found in the Lexus LS400. Although it achieved FAA certification, the company eventually clipped its own wings and abandoned plans to build its own airframe.

At sea, however, things were different. At the same time Lexus was getting off the ground, Toyota sought to bring its seemingly unstoppable momentum to the world’s waterways. Ultimately, Toyota’s marine business targeted the ski boat market in a bid to lure Camry owners with lake homes further into the fold.

The engineering effort that went into the company’s initial wet and wild foray of “Epic” tow boats, as with Lexus, was extensive and impressive, focusing on core company values like reliability. Unfortunately, everything else required to actually, um, sell boats was not as comprehensively considered, and that circumstance—combined a weird twist of fate in the production department—condemned Toyota Marine to be no more than a footnote in boating history.

Getting off the ground

Toyota had been working together with Yamaha’s own boat builders for several years before deciding to strike off on its own. In fact, a Marine Business Planning Office had been in place since 1990 as Toyota worked on various sea-going projects. The company had a pretty good idea of where its strengths lay, and where the newly-minted marine division would require assistance from outside.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

As with its aviation pursuits, the automaker’s comfort zone centered on engine development. Toyota had already contributed a Land Cruiser-based marine diesel engine to Yamaha’s portfolio of small watercraft, and in seeking a high-performance platform for its own line of boats turned to the venerable 1UZ 32-valve V-8 upon which Lexus built its reputation.

The plan seemed sound. Toyota reached out to California’s Dave and Shauna Triano, a pair of wakeboarding enthusiasts at Shadow Composites Design Studio, to create a clean-sheet design that could appeal to high-end buyers by offering outstanding practicality and performance in the same package.

Dave had worked as a designer at Toyota’s CALTY studio in California for five years prior to leaving to pursue his passion for boats. Also involved in the Toyota Marine design derby was Mark McNeil’s Marine Design and Development in Florida. The boats themselves were to be built at Maritec Industries in Orlando, Florida, which was planning a million-dollar manufacturing plant to keep up with the forecasted demand for Toyota’s new product line.

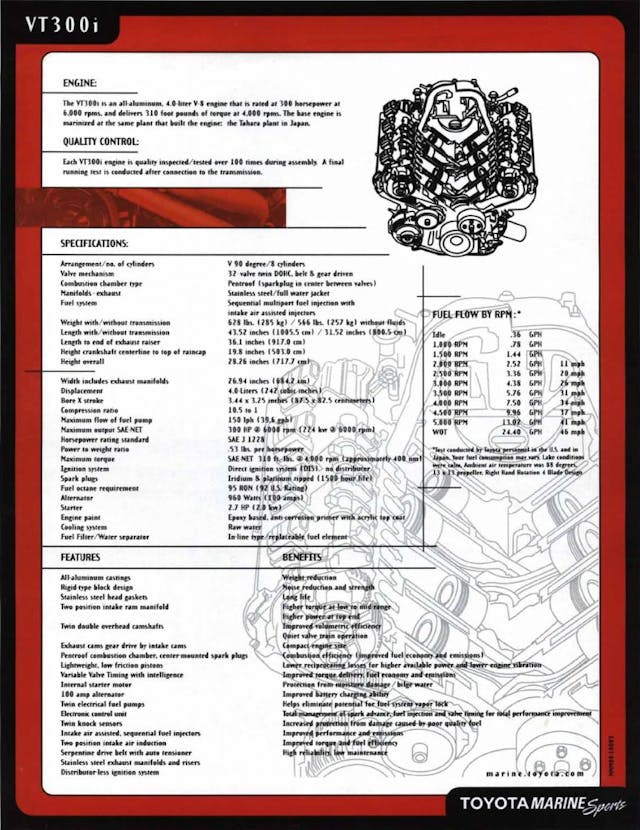

Toyota’s efforts to waterproof the 1UZ took place in Tahara, Japan, at the same shop where the Lexus LS400 was assembled. The process involved rigorous testing to prove that the 1UZ could operate flawlessly in a cold, wet, and often unforgiving environment. It also gave engineers carte blanche in tuning the motor to produce as much power as possible without having to worry about idle manners or emissions controls. Renamed the VT300I, this water-bound version of the 1UZ generated 300 horsepower, or close to 50 more than it did in its original automotive application. It was also good for 310 lb-ft of torque.

A trickle of boats

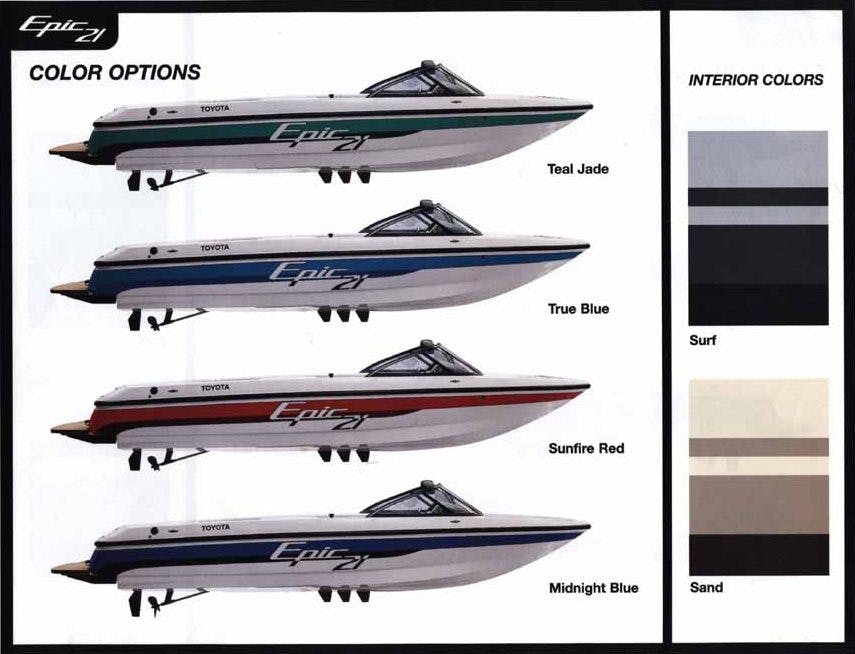

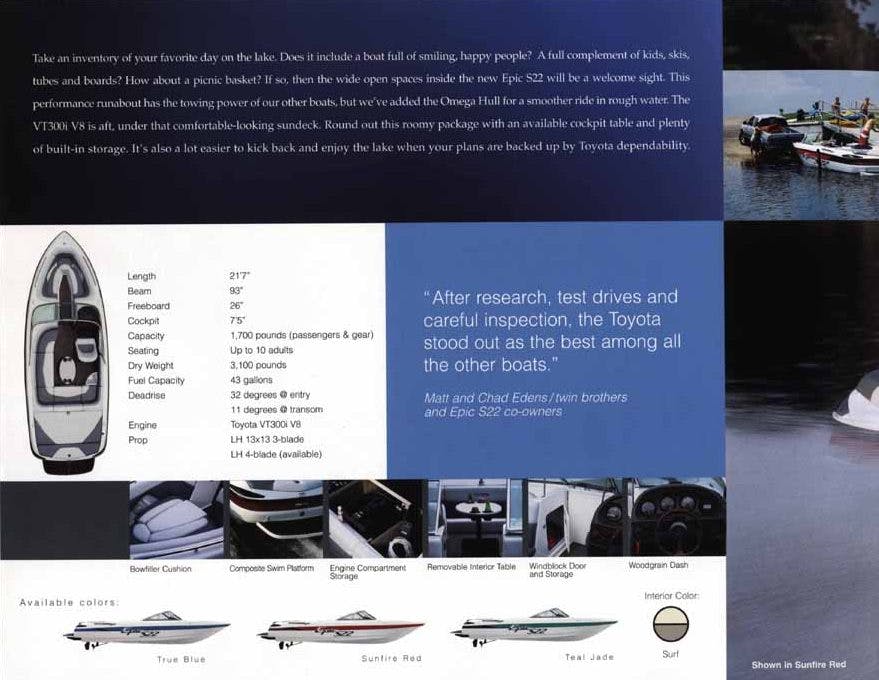

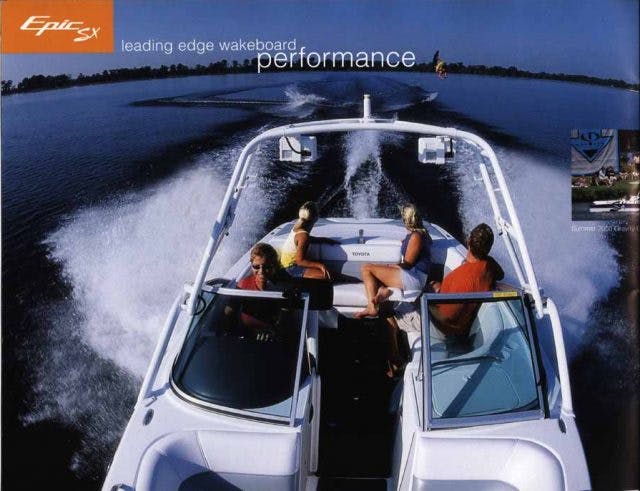

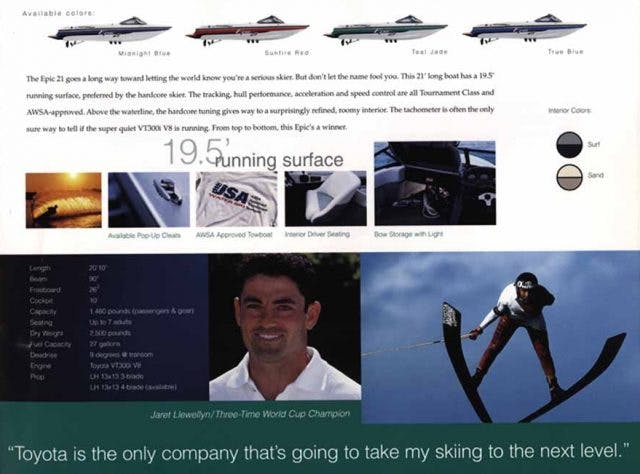

With the Planning Office revamped as the Marine Business Division in 1997, the Toyota Marine Sports brand launched the year after with the Epic 21. This 21-foot inboard eventually spawned both closed-and-open bow models, eventually evolving into a pair of V drive models: the S22 and the SX (with the engine pushed to the stern of the boat to improve cabin space and boost the wake encountered by those being towed behind). The SX, which appeared in 2001, was the pinnacle of Toyota Marine’s development, with a number of high-end features that elevated it to the forefront of wake boats of its era.

Yet, amid all of this technological prowess and strong reviews (the Epic was even featured at the Gravity Games two years running, back when “extreme” sports were having their media moment), Toyota quickly discovered that building boats and selling them required much different approaches. This especially proved true as the company ventured into the world of watercraft hoping to adopt the same philosophies it understood as essential to establishing a luxury car brand.

At the International Marine Trades Exhibit & Conference in 1997, Toyota Marine’s National Sales Manager, Glenn Sandridge, was regularly questioned as to why the Japanese auto giant was targeting the ultra-niche wake boat business. Sandridge stated that the Epic was the tip of the spear for Toyota as it felt out the industry, and that board members had been a little gun-shy about diving into multiple segments at once.

With the total American speedboat market reaching a mere 5500 units a year in the 1990s, it ended up being a pointy tip indeed—especially in light of the $30,000 starting price tag for the boat (roughly $50,000 today). Making matters considerably worse was Toyota’s decision to produce a mere 500 boats per year. Limited volume made it very difficult for dealers across the country to maintain any inventory, which in turn directed sales staff’s attention away from the Epic series and toward more readily-available models that customers could actually touch and see. Dealers used to selling at least 10 examples of a given boat per month were struggling for one-tenth of that output from Toyota Marine’s inventory, and it was virtually impossible for any headway to be made with new buyers, even if they were genuinely interested.

Soaking up the Florida sun

The final nail in the coffin: a serious production flaw that required a full recall and replacement of every Epic 21 sold. It seems that Maritec had left the molds for that model in direct sunshine long enough for it to distort the hull, creating a condition called “chine lock,” which occurs when so much turbulent water and air accumulates under a boat’s hull that its chines and rudder can’t get any foothold on the water. As a result, the craft won’t respond to steering inputs while it’s being driven at speed, requiring the pilot to back off the throttle to reposition the boat.

Although a buy-back sounds expensive, given the small number of boats sold by the time the issue came to a head its cost it was far more palatable than potential injury lawsuits. Still, dealers weren’t happy (many of whom had discovered the chine lock issue while doing their own initial testing) and the misstep further alienated Toyota from its distribution network in the United States. Facing growing financial pressures, Marine Sports folded in 2001.

As at sea, so in the air

Despite the rough seas of 20 years ago, today the Epic 21 and its various offshoots enjoy a solid reputation among the few and the proud who were actually able to procure one. Easily found for sale in the used market, boaters enjoy the features and technology offered by Toyota’s bulletproof 1UZ-to-VT300I conversion, as well as the Shadow Composites (now Triano Marine Design) hull and the strong wakeboarding and water skiing features baked into the platform.

As for Toyota’s watersports dabble, it continued off and on for the next two decades by way of the Japanese-market Ponam series of larger cabin cruisers (built in partnership with contractor Yanmar), several Lexus yacht concepts, and even hybrid boat designs intended more to gather headlines than court paying customers.

Looking at the marine business in this way also raises interesting questions about how the Epic experience may have influenced Toyota’s decision to back away from general aviation. After extensively testing the 1UZ-derived FV2400-2TC over American skies—and engaging Burt Rutan and Scaled Composites to help it make headway in the six-passenger plane market—the effort culminated in the TAA-1. This experimental plane had a high profile as part of Toyota’s overarching plan to help replace what the company felt were a large number of aging airplanes in America. Then, just a year or so following the Marine Sports failure, talk of the TAA-1 and the FV2400-2TC faded into the background, only rarely heard on the lips of executives and even then only under direct questioning by curious media.

It’s understandable to see a connection between one niche market failure and the possible trepidation about stumbling into another. Still, you have to admire Toyota for both dipping its feet in the water and elevating its vision way above solid ground.