Media | Articles

Flat Toppers: On the USS Nimitz, young people do serious jobs

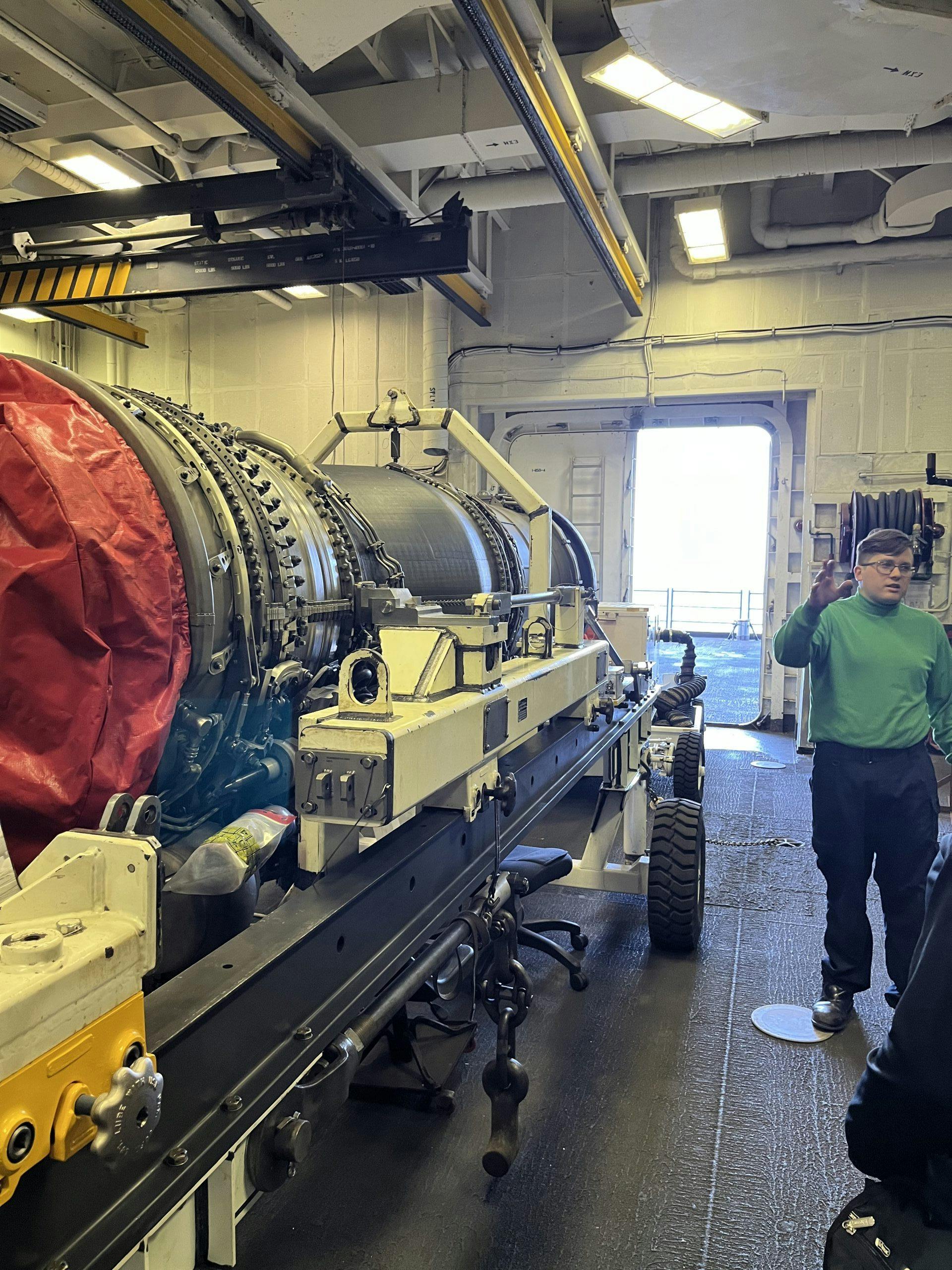

Rethan Robison was a 21-year-old car mechanic living in San Antonio, Texas when he decided to join the Navy. Now his shop is at the very back of a thousand-foot-long, 97,000-ton, $8.5-billion, nuclear-powered instrument of U.S. foreign policy. The aviation machinist, third class repairs jet engines aboard CVN-68, the USS Nimitz aircraft carrier, including the low-bypass turbofans that drive the Navy’s F/A-18 Super Hornet fighters. Common problems include fluid leaks and hard landings on the carrier deck above, which, Robison says, shake the 2100-pound turbines so badly that their whirling blades momentarily scrape the inside of the engine housing—to disastrous effect.

Robison’s shop can tear down and rebuild a Hornet’s F404-GE-400 turbofan in as little as a day and a half. “It’s a lot cleaner than working on cars,” he says, of the job he’s had for three years. “There’s more moving parts, but they’re a lot bigger.” When the engine is back together, Robison and his crew wheel it out to a patio on the ship’s fantail where it can be tested and run all the way up to screaming afterburner.

If that sounds like a cool job, it certainly looks like one. Robison—he says his mom made up the name Rethan—seems to think it’s cooler than fixing cars, though he admits to missing his ’85 Chevy El Camino back home.

The Navy invited us, along with a dozen other civilians, for a 24-hour stay aboard the original supercarrier, which launched the Nimitz Class of nuclear carriers when it was commissioned in 1975. Variously nicknamed “Uncle Chester” and “Old Salt,” the Nimitz was on a seven-week training cruise from her home port in Bremerton, Washington, when we came aboard, steaming about 75 miles offshore of San Diego. Besides hosting “CQs,” or carrier qualifications for Naval aviators, it was also a training run for everyone from jet-engine wrenches to electronics specialists to cooks to nuclear reactor techs to the bosun’s mates who oversee the ship’s gigantic steering, berthing, and anchoring equipment.

It takes 3000 people to run the Nimitz, a number that swells to over 5000 when the carrier’s eight separate squadrons come aboard with their aviator and ground crews. One-third of that number turns over every year as sailors go on to new jobs in the Navy or muster out. Thus, the Nimitz has spent far more of its nearly 50 years in America’s arsenal not as a weapon, but as a giant technical college at sea.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

And what a place to go to school. Some stats: the ship is 1092 feet long and 23 stories from keel to mast, with a 4.5-acre deck and similarly sized hangar bay underneath that together pack in 65 aircraft during full deployments. Two Westinghouse A4W nuclear reactors flash enough water into steam for the ship’s turbines to produce 140,000 shaft horsepower each. They also supply the ship’s four catapults with up to 65,000 pounds of instantaneous airplane-flinging thrust. At the ship’s published flank speed of 33 knots, her four screws are turning about three times a second, which doesn’t sound like much until you realize that each five-bladed brass prop weighs 33 tons and is 25 feet in diameter. The ship’s range is characterized as “unlimited,” the reactors being refueled only once every 20 years (the last pit stop being a top-to-bottom refit that took four years).

After some cursory instructions on how to don a self-inflating flotation collar and the “cranial,” the snug-fitting helmet/ear protector worn by deck hands, we were ushered through hot turbine blast and into the belly of an idling Grumman C-2 Greyhound. The twin-turboprop Greyhound has been the Navy’s prime “carrier on-board delivery” transport, or COD, for longer than the Nimitz has been afloat. Everyone just calls the airplane “the Cod.” Passengers sit in its uninsulated, mostly windowless hold, facing the rear cargo hatch, separated from their belongings lest a loose item go flying during an arrested landing or catapult takeoff.

During the deafening, 39-minute trip out to the Nimitz, there was little to do but, as they say on the airlines, sit back, relax, and await the bang of the tailhook smacking the deck, followed by the attendant three or four Gs of lung-squeezing deceleration. After a hand-wave of warning from the crew, the Cod crossed the Nimitz’s threshold at 120 mph, snagged a wire, slammed onto the deck, and came to a stop in less than two seconds, ramming us deeper into our seats with an audible “oof!” The airplane’s beaver-tail rear hatch immediately dropped, a shaft of light pouring in. We could see ship’s hands milling around and, in the distance, the cobalt-blue Pacific.

A small team of public-affairs officers, some of whom were pulled off other jobs for our visit, hustled us belowdecks and to the commander’s office. Carrier commanders come from the ranks of naval aviators, and Captain Craig Sicola was a helicopter and Hornet driver before being sent to “nuke school,” where future commanders are trained in the ways of atomic ships. Aboard the carrier, he sits at former Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz’s actual desk and works on a glass top under which is a full-scale reproduction of the man’s hand-drawn battle plan for the world-changing Battle of Midway. Old Salt himself, minus the finger he lost to a ship’s machine in his early years, stares down from a life-size portrait over the desk. If that isn’t daunting enough, Sicola’s job as mayor of a small, nuclear-powered city keeps him endlessly busy.

Forget the cigar-chomping, order-barking Top Gun stereotype of a carrier commander; Sicola is rail-thin and soft spoken, with trace flashes of grey at his temples. His biggest problem isn’t cocky jet pilots wanting to buzz the tower but maintaining morale and work efficiency with a crew that may be gone from home for more than six months. He said, “You have 18-19-year-old sailors away from home for months at a time, I’ll let you work out the rest.” During our visit, he was unsuccessfully petitioning his superiors to follow the lead of most states and remove the Covid-19 mask rule, still in place aboard (though, we saw, unevenly followed).

At that point, the ship’s executive officer, Captain Joshua F. “Spoiler” Wenker, a former flight officer on the E-2C Hawkeye, showed us how he got his call sign by noting that there would be no fixed-wing operations during our visit. Which meant no jets. The Hornet squadron that had been qualifying shortly before our arrival had finished early—a tragically timed case of military efficiency—and the deck would be much quieter save the arrival of a trio of new CMV-22 Ospreys. Already in service with the Marines and Air Force, the CMV-22 is the Navy’s version of the standard tilt-rotor, V-22 cargo hauler, and scheduled to replace the Greyhound by 2024. Osprey rookies, many of them former Greyhound drivers, would be attempting their first carrier landings in the twin-rotor craft during our visit.

I wasn’t aboard five minutes before I met someone from my hometown of West Bloomfield, Michigan. Lieutenant (j.g.) Alex Przeslawski works in information technology, probably a code for electronics warfare, when he isn’t showing visitors around. Everywhere you look, pipes, valves, cables, and electronic boxes line the ceilings and hallways of the Nimitz’s endless miles of passageways. Much of it appears to have been slapped with a coat of white paint about a dozen times. Przeslawki told me that probably ten percent of the wiring aboard the Nimitz is derelict, overtaken by newer technology in the nearly 60 years since her keel was laid, but never removed.

Cranials, goggles, and double ear protection are required on the ship’s deck. After a seemingly endless climb up the ship’s near-vertical stairways, we walked out on “vulture’s row,” an observation balcony overlooking the vast flight deck. The Ospreys were coming in for practice touch-and-goes, their pilots gingerly approaching the ship’s fantail, hovering, and setting down with the twin rotors—Osprey pilots call them “pie plates”—visibly pitching and shifting to keep the craft stable in descent. A few pilots misjudged the heaving deck, coming down hard enough to give a good shake to the wings and engine pod, before bouncing back into the air for another try. As the Ospreys taxied past the ship’s island in preparation for take-off and go-around, the noise and air pulses from the beating props shook the carrier’s superstructure and the chests of those watching.

The current Navy Osprey, the CMV-22B, looks like two helicopters strapped to a beluga whale. It is identifiable by larger sidepods on the fuselage that hold another 300 gallons of fuel (equal to an hour in cruise and thirty minutes in hover) compared to the Marine and Air Force versions. The downwash from the twin 38-foot-diameter rotors is such that most of the deck is cleared of personnel lest someone be blown overboard. That necessary operating room is one of the downsides to the complex Osprey, which has also proved a problematic maintenance hog during its time with the other armed services.

Compared to a jet or even the MH-60 Seahawk and Knighthawk helicopters that deploy with the carrier, the Osprey has an incredible number of moving parts. Not only do the huge rotors tilt to turn the Osprey from a helicopter into a faster, more efficient, and longer-range turboprop aircraft, each 6000-hp Rolls-Royce Liberty turbojet engine is interconnected through shafts and a central gearbox. Thus, each engine can operate the opposite rotor in case of an engine failure. When parked, the blades fold up and the entire wing swivels in alignment with the fuselage, for tighter packing on the ship’s crowded deck.

Upsides of the Osprey include the ability to fly to other vessels in the task force, an option not possible with the Greyhound, as well as the ability to land ashore just about anywhere. The Osprey does have one other very cool feature: rotor-blade tip lights, which turn the pie-plate edges an interstellar green for pilot and ground-crew reference at night. Later, as we watched the same pilots do their night qualifications in heavier winds and seas, the eerie green rings, rapidly teetering and changing shape, served as vivid illustration of just how hard the Osprey’s flight computer works to keep it stable.

The pilot doesn’t have collectives to control the rotor pitch as in a helicopter, just a control stick and a throttle, explained lieutenant commander Charles “Chuck” Yeargin of Independence, Missouri. Yeargin is a former Greyhound driver who was qualifying that night as part of VRM-50, one of the Navy’s fleet-logistics squadrons just transitioning into Ospreys. The V-22’s computer takes the simplified inputs from the pilot and translates them into pitch and power changes. “The aircraft is fly-by-wire,” he told us later. Was it harder than flying the 60-year-old Greyhound? Yeargin paused, obviously weighing the cons of the Osprey’s complexity against the pros of not having to slam a large airplane onto a carrier deck at 120 mph at night and in weather. “It’s definitely different,” he said, finally. “It’s smaller inside than the Greyhound, so you run out of space before you run out of power.”

When the Nimitz was new, wags said the U.S. could hand the ship over to the Russians and it would take them a hundred years to figure out how to operate it. It’s certainly taken the Navy that long, starting from the first shipboard landing, in 1911, flown by Eugene Ely in a 75-hp Curtiss A1 Triad. Now, as the nearly 50-year-old Nimitz sails along, she’s in a constant state of falling apart. Plumbing drips, wires fritz, hydraulics fail, paint peels, and any metal exposed to the salty sea air immediately rusts. Despite having four desalination plants aboard that produce 400,000 gallons of fresh water daily, supplies are said to be chronically short. Thus, in addition to the endless training, much of the crew’s dawn-to-dusk, seven-days-a-week work routine is consumed by endless maintenance.

Way up front, in a huge triangular room called the fo’c’sle, the two 60,000-pound anchors hang from chains the thickness of tree trunks. Lieutenant commander Clint Tergeson, a straight-out-of-high-school enlistee who now runs a 77-person department responsible for the sailing of the ship, described the anchoring procedure. Everything is done in careful, well-practiced steps, with orders called and repeated back before the friction brakes are released on the giant capstans and their attached wildcats (a sort of anchor-chain sprocket). At that point, gravity does the rest, ending with a big splash.

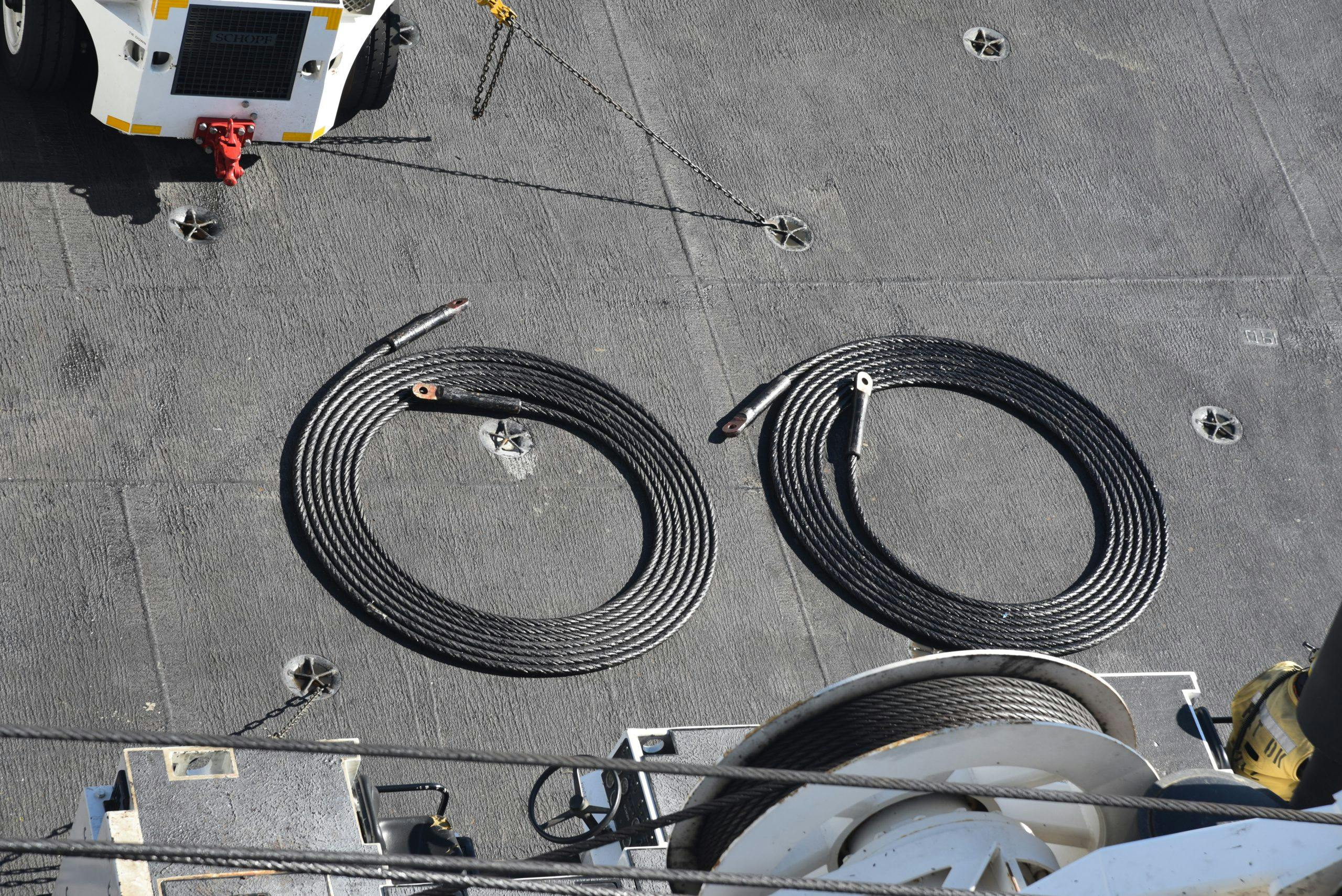

Here’s an example of just one maintenance item on an aircraft carrier that you should consider before buying one: The Nimitz’s thousand-foot anchor chains are comprised of 360 chunky iron links, each three feet long and weighing 250 pounds. The whole chain is divided into 12 sections, or “shots,” each section tethered to the next by a special link with a removable center piece. Every two years, the 45-ton chains must be run out onto a barge and the shots disconnected and moved around so that they all serve equal time at different points of the chain, thus evening out the wear from stress and salt-water exposure. And you thought it was a pain to change your oil.

If the ship goes out on a deployment, typically six months, it will spend at least that much time in maintenance after. In June 2020, the Nimitz left port in San Diego on what sailors now call the “Covid Cruise,” an unusually long and infamous deployment that stretched more than 11 months and over 99,000 miles. The ship was headed home and turned back five times for naval needs in the Middle East and far Pacific. At sea, it was impossible to fly in refrigerated vaccine, so the crew was instead isolated and only allowed off the boat once in that period, in a secure parking lot where the Navy set up carnival rides and games to take the edge off. It only partially helped; ship’s chaplain Charlie Mallie, a New Jerseyan with tattoos up both arms from his “punk era” days, told us his counseling sessions leapt by almost 400 percent. But at least there were no reported coronavirus cases, unlike other ships.

“They did the best they could to keep up morale,” said Jalen More, a Covid Cruise veteran and culinary specialist from Virginia Beach who sat down with us for breakfast in the sprawling enlisted mess. After the third turnaround, he said, “you could see it on their faces, everyone was sad.”

Still, that was an outlier in a national service that tries to keep its young enlistees motivated by moving them to new jobs every two or three years. More was soon to be reassigned, he said, and hoping for a posting in Italy or Florida. Aaron Robison—he was surprised to learn of another Robison in the jet-engine shop—is a parachute rigger chief from Coos Bay, Oregon. After 15 years in the Navy and 11 supporting SEAL team desert deployments, Robison was on his first ship assignment and heading a seven-member rigger team whose motto is “The Last to Let You Down.” Fighting monotony among his reports and keeping up the attention to detail required to safely maintain parachutes and other safety gear was his greatest challenge. “The way I look at it, the final, last-ditch effort to save a pilot’s life is our equipment, so that brings me a lot of job satisfaction,” he said.

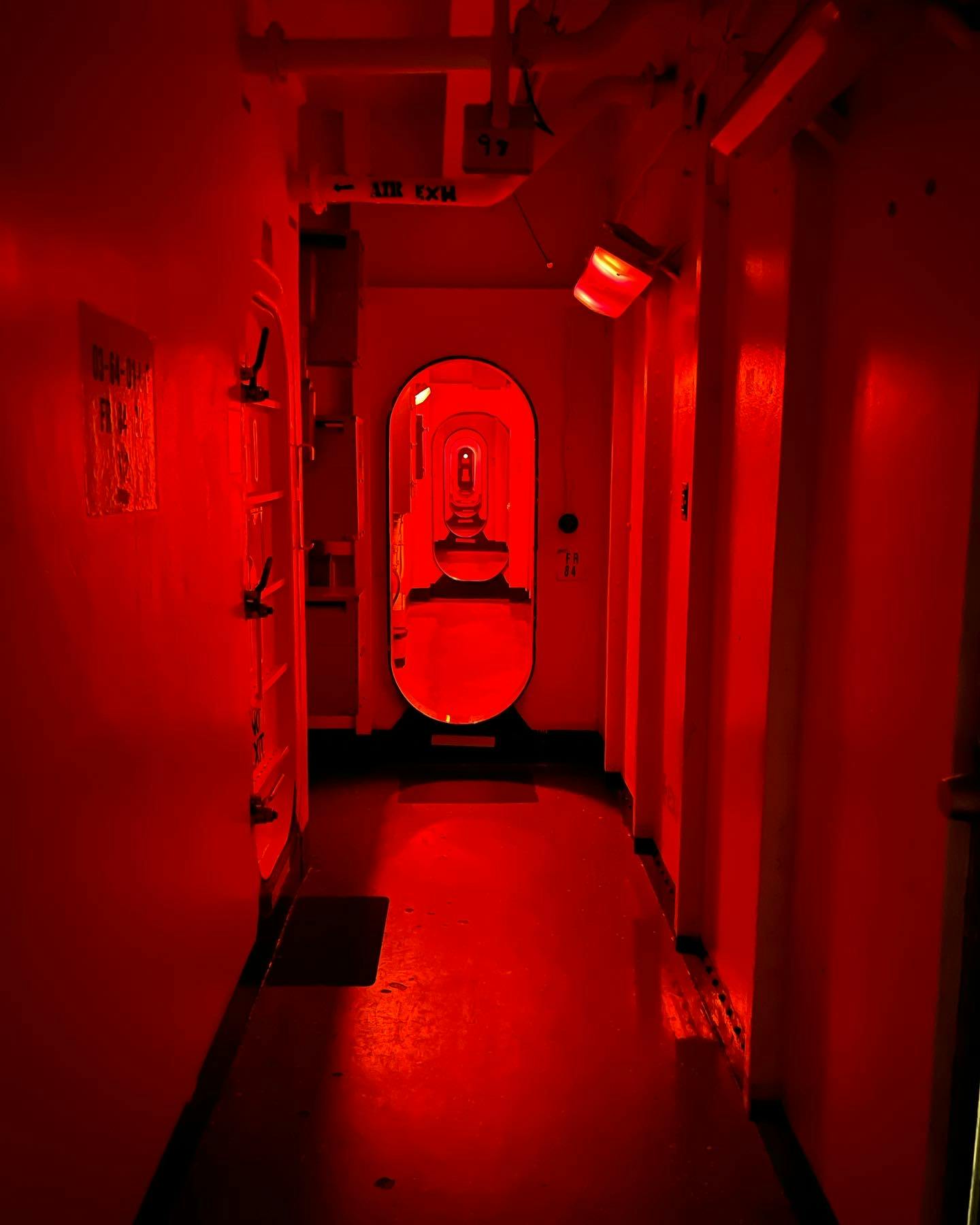

Our group hiked past many closed doors and darkened utility rooms as we navigated the confounding maze that weaves through the Nimitz’s bowels. The night we spent in the double-bunk-bed visitor’s quarters was, we were told, exceptionally peaceful. The quarters are right underneath the flight deck—indeed, right underneath the jet-blast deflectors that pop up behind the aircraft before they launch. A shared head—a bathroom—was down the hall, through a couple of “knee knockers,” or oval passageways through the ship’s bulkheads. With a reduced complement aboard during our visit, the passageways leading off into shadowy reaches, lit red at night, were eerily quiet save the ever-present hum of unseen machinery.

The whole feeling aboard the Nimitz is that of a medieval castle at sea. Generations of sailors and aviators have walked the ship’s hallways in service of their country and their own betterment. Perhaps no generation needs the latter more than today’s, in the age of digital ephemera, where nothing seems to matter but clicks and likes. For young people—the average enlisted age on the Nimitz is 23, just 26 for officers—who are seeking more substance from life and aren’t ready for or don’t need college, the military is a good place to start. Hook the three-wire in your supersonic F/A-18 and the kid maneuvering you to your parking spot may only be a couple years out of high school. Ditto the kids who pumped your fuel, overhauled your engines, fixed your avionics, served your breakfast, and steered the thousand-foot ship on course.

It’s not Top Gun. There’s no pounding rock soundtrack or horsing around in $60-million jets, but it does look like an adventure. We met tired people, we met some people who seemed bored and homesick, but we didn’t meet a single person who said they wished they hadn’t joined up. Several said the Navy was way better than what was available to them back home.

Engines roaring, the C-2 lined up on one of the Nimitz’s forward catapults. Facing backwards in our seats, we were told to put our chins down on our chests. I hooked my thumbs around my shoulder belts and waited. And waited. BANG! The 44,000-pound airplane lurched forward, hitting 120 mph in less than two seconds. Our heads snapped forward, then backwards, as the catapult released and the airplane, now aloft, momentarily decelerated. Cheers erupted in the cargo hold, barely heard over the straining turboprops.

No, we didn’t get to see jet operations, but literally every single other thing we saw and every person we met was fascinating. We hope to get back soon to see some Hornets, or maybe even the new F-35C Lightning II, the Navy’s first stealth jet, catching some traps. You know, if the Navy will have us.