Media | Articles

Zen and the science of motorcycle batteries

I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: Subtle modifications are the best ones. Unfortunately, one such combination of old and new nearly cost me my butt and my friend a low-mileage, original Kawasaki motorcycle.

It all started when he offered to give me the afternoon to exercise his vintage bikes. It’s an opportunity one doesn’t turn down, especially when the friend’s the kind of guy who scolds you for not riding his bike hard enough: “I can hear you all the way to curves on the highway, and you need to let this bike get on the pipe!” Don’t have to tell me twice.

Negotiation was simple. In return for the ride experience, I agreed to provide riding notes for a book he is working on and bring a few of his bikes back up to running order. A little carb work here, unsticking clutch plates there, and putting new batteries in just about everything. Since some bikes were waking from years of storage, that meant a couple pairs of tires to install. No big deal, and it’s why I keep tools in my van.

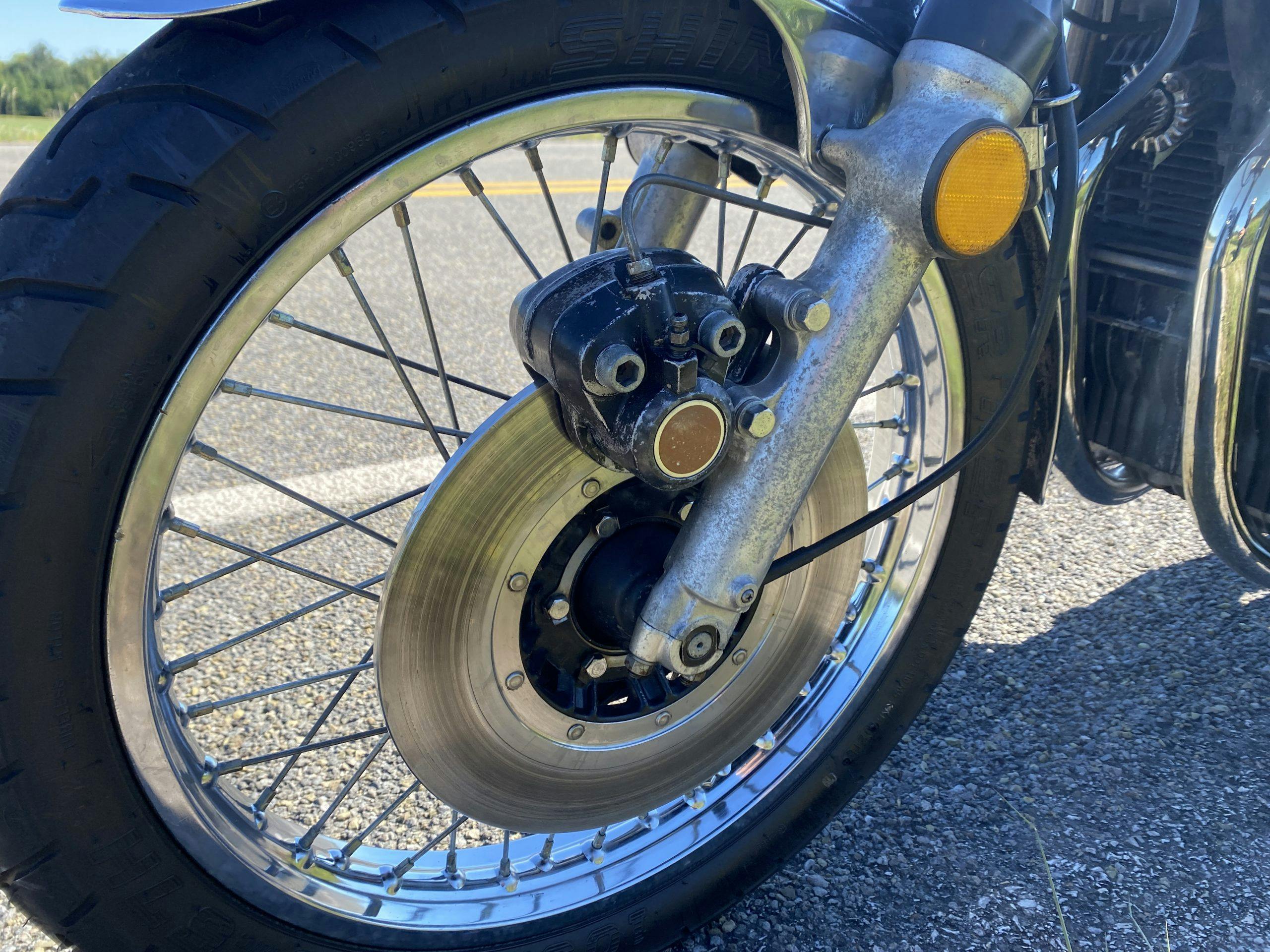

The last bike to get attention was a 1973 Kawasaki Z1. Since it had run most recently, among the fleet of eight or so, it needed the least work. The gas in the tank wasn’t even sour, but the battery had been pilfered for some other project, so I was directed to a small stack of new batteries in the corner of the shop. The owner is not a penny pincher and had broken out the checkbook for a bunch of very nice, very lightweight, lithium-ion batteries. Replacing lead-acid batteries with these updated, chemical-charge cells is a common strategy to shed weight. One like this in the Z1 can take as much at six pounds off a bike. That’s meaningful change. Oh, and these batteries are often more resilient during long-term storage. Win/win for a guy who owns a bunch of motorcycle in northern Michigan, snow-bound for months of the year.

I threaded the bolts for the positive and ground leads and tucked the little, red and black battery into the factory battery box before padding it with a couple chunks of styrofoam so it wouldn’t shift and arc the terminals while I was riding it. After I snapped the seat down, it only took a slight tickle of the starter for the 900cc inline-four to sputter to life. 15 or 20 seconds later, it had cleaned up and was thrumming a smooth idle. I let the bike warm up a bit as I put on my leather jacket, helmet, and a pair of gloves. As I swung a leg over the bike and picked up the kickstand, the owner popped over to point at the tachometer. “The bike only really comes alive over here,” he said, index finger circling 8,9, and 10 on the gauge.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Now I was conflicted. This was not my motorcycle, and it is both very original and quite low-mileage. Last thing anyone wants to do is blow up a bike they don’t own and can’t afford. Before I could even start my protest, my friend shut me down.

“Seriously, you have to wring it to make this bike work.”

Headed for the curves in the highway, I gave it the beans. I’ve ridden a handful of other inline-fours of this era and had made sure to read the early reviews of the Z1 before the ride, which meant my expectations were realistic. The chassis was as noodly as one would expect a bike of the era to be, yet it also was sharp, making me feel right at home turning in and apexing corners—as best I could, while staying in my lane.

A big, fast left opened up to a nice, half-mile straight run between two open fields. The tach was at 7000 right at the apex and, as I rolled on the power, the bike picked up and felt like a needle in the groove of a record.

The record scratched.

A slight loss of power, a cough through the carbs, then a puff of smoke and total engine shutdown. I had the clutch covered in less than a moment and smoothly braked into a convenient driveway to face what could only be bad news. No oil on the ground or new holes in the cases—in fact, no fluids spilled at all. Smoke was still tracing from under the seat in long whispers. Had the air filter caught fire? I didn’t know.

This was not when I wanted to learn how to open a Z1 seat latch. Where was the seat latch? That’s a concerning amount of smoke. I had installed the battery in the bike under the seat and closed it, but it was open when I started working on it, so now I didn’t know exactly where the latch was or if I needed the key to operate it.

Sheer panic.

When I finally got the seat flipped up, I was met with a cloud of fumes that probably took three years off my life. That brand-new battery was so hot it had melted off its stickers and was cooking the plastic case. Everything near it was hot. After an unsuccessful attempt to undo the battery connection with my pocket knife, I discovered this bike still had its original toolkit. Lucky me. The factory-packed slip-joint pliers made quick work of disconnecting the terminals, allowing me to reach in a gloved hand and yank out the battery so both it and I could cool for a minute.

I took a deep breath, for clean air reasons and clear head reasons.

After some mental regrouping, and after failing to get the bike’s owner on the phone, I took a chance. I’d try to bump-start the Z1 so I could get the three or so miles back to the garage. Not all electrical systems will function without a battery installed, but I was not about to put that overcooked chunk back in the bike. Luckily, the Z1 fired right off in second gear, idling happily while I put on my helmet and balanced the battery on my right leg. I wasn’t about to abandon a potential fire hazard in some stranger’s driveway.

Back at my friend’s garage, the diagnostics began nearly instantly after I told my story: “Oh, that means the regulator failed. It’s a common issue on these.” It took me a second to understand the timeline of events that lead to that battery popping. Essentially, it looks like this:

The engine’s high-rpm run led to the charging system producing a little extra current. The regulator would typically dump this to ground, but the excess current came fast enough that the regulator either was overwhelmed or failed independently, in a way that it stopped bleeding that excess to ground and instead overcharged the battery. (This is where it gets a little nerdy, so fair warning.) Now the situation became a chemical problem rather than an electrical one. When a traditional, lead-acid battery receives extra current, it will boil off the acid and display sulfation, in which part of the acid is deposited on the plates of the battery, thus diminishing the battery’s ability to accept a charge. Lithium-ion batteries are much less forgiving. They simple cannot absorb overcharge that way. Once plating of the metallic lithium occurs, it compromises the safety of the battery. Thermal runaway is far more likely in a li-ion battery than in a lead-acid one.

Thermal runaway. Awful scary term for something that happened about two inches underneath my precious parts while traveling at highway speeds. Luckily, the Kawasaki is not damaged and its charging system can be easily repaired. More importantly, I am unscathed—and more wary than ever of mixing old and new technologies.

I’m surprised a LiPo battery intended for vehicular use doesn’t come with a dedicated regulator, or at least a requirement to add one. They’re fantastic tech, pack a brutal wallop for their size and weight but have quite a narrow safe charge rate range. I wonder if the unit has a limiter concealed in its housing that failed?

AGM? Yes, all day and every day in older vehicles. Li-Ion? No. Too unstable for the exact reasons you found.

Barbecuing one’s bits over a lithium fire is just not on. Please do be careful.

I decided to replace my soon to die lead acid battery with a Lithium version in my custom 2004 Road King. As far as I know the one thing that has not been done is change the original charging system.

I’ve learned a lot about chargers and tenders from classic car guys I know. Some have rows of valuable cars and motorcycles that all need to have their batteries maintained properly. A few years ago I started to notice the top pick has been changing to the brand NOCO. Since then that’s the only chargers I trust. They do not overcharge due to their state of the art technology. Sorry this sounds like I must work for them, I do not, I just want things that are reliable and make my batteries last safely, and as long as reasonably possible. They work well for me.

In July when I had decided to ride my Road King to Sturgis, about 1200 miles all total, I knew I needed a new battery. After researching the options I found out NOCO now makes lithium batteries for bikes. They were in short supply but I managed to find one in the correct size/specs. It is very light weight and is a fraction shorter in height making it a little easier to install. I was a little skeptical about the stock charging system. We included compression relief valves the last time we had the heads off just to make it a little easier on the starter. After installing the new lithium battery I found it no longer needs any help. the cranking amps is sufficient to start on the first or second revolution every time.

So far this battery is far superior to any I’ve ever had. Even after sitting for a time it has not dropped the slightest bit, without a tender attached. I will now be placing the bike in storage until spring. I plan to start and check it regularly to see how the battery levels do without a tender. We’ll see how the long term performance comes out.

As to cost; a good lead acid battery will run $150-$200 or even more. This NOCO NLP30 w/700 cranking amps for full size touring bikes is $199 on their website, probably less from some secondary suppliers? I’m sure other brands of lithium batteries for motorcycles are now plentiful, but my experience with this Co. has been nothing but positive.

Thank you for a fine ‘outline’ on the hazards of Li batteries. I owned a Kawasaki 750 ( Like the image ) straight from the crate. It was a true ‘Rice Rocket’ It broke my heart to sell it to pay a ‘speeding’ ticket – OUCH!

[ Vivere et Discere ] live and learn. Your a good writer.