Media | Articles

When to take the Check Engine Light seriously

Nearly everyone who drives a car built since the mid-1990s has experienced the sinking feeling of the Check Engine Light (CEL) coming on and the frustration of trying to figure out what to do to make it go out.

The CEL is part of the federally-mandated Onboard Diagnostics (OBD-II) system, installed in every car sold in the United States since 1996, that that monitors the health of the car’s emission control system. The design of OBD-II includes a standard trapezoidal-shaped 16-pin connector into which an OBD-II code reader or a scan tool can be plugged. Part of the system’s purpose is that it allows any repair shop or do-it-yourselfer to diagnose and repair the car’s emission control system by plugging in an inexpensive code reader and downloading the codes that tell you why the CEL is lit.

In theory, OBD-II is a great idea, but in practice, there are several things that can make it frustrating. First, its federally-mandated universality means that the information it provides is never going to be as specific as the dealer’s plug-in diagnostic computer. That is, an OBD-II code reader might tell you that the problem is in, for example, the secondary air injection system, but it doesn’t know what the details of that system are on your particular make and model. This is part of the difference between an inexpensive OBD-II code reader and pricier model-specific scan tool. The former will only tell you the generic emissions-related codes, whereas the latter can tell you more detailed brand-specific codes.

Second, the generic codes that an OBD-II code reader provides can be pretty obtuse. For example, P0442 is the code for “minor evaporative leak.” You have to do some digging to even understand what that means, and then read up on a model-specific forum to find out what, on your car, is most likely causing the code to be thrown. (And, for the record, the whole thing about “if the CEL is on, tighten your gas cap” is perilously close to being an urban myth. It’s almost never that simple.)

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Third, taking the code too literally can sometimes cause parts to be needlessly replaced. For example, oxygen sensor-related codes send people scurrying to order and replace oxygen sensors, but the cause can instead be that something else is causing the sensor’s reading to be out of range, such as a failed catalytic converter. (For more information on this and other OBD-II issues, see my electrical book.)

Lastly, there are many things that can light the CEL, and the majority of them aren’t serious. You aren’t likely to damage your engine or contribute to the warming of the planet if, for example, the CEL is lit due to a code for a minor evaporative leak. As a consumer, few things are more frustrating than being quoted $1500 for a repair whose sole purpose appears to be to make the CEL go out on a car that’s running just fine. Unfortunately, in states that have annual motor vehicle inspection, you often have little choice but to pay for such repairs (or figure things out for yourself), because having the CEL on is usually an automatic inspection failure. Some cars try to prioritize the serious codes by having two lights, one being a generic “Check Engine” light, and the other being a more insistent-sounding “Service Engine Soon” (SES) light.

And this brings us to today’s topic. There is one area where the OBD-II codes are quite reliable, and that is in the area of cylinder misfires. If the CEL or SES is lit and the car is idling and running rough, and you plug in the code reader and it pulls up a code that says “Cylinder X Misfire,” the odds are strong that cylinder X has a bad stick coil, and that replacing it—often about a 15-minute process involving an approximately $25 part—will fix the problem.

Misfires are caused by a spark plug not firing, or firing irregularly or weakly. They’re one of the OBD-II-flagged issues that you really should fix as soon as possible. The OBD-II system is sensitive to misfires not only because of the emissions from unburnt gas, but because unburnt gas is damaging to the catalytic converter. For this reason, if a misfire is detected, it will usually cause the CEL (or the stronger “Service Engine Soon” light) to be lit immediately. The fewer the number of cylinders in the engine, the more strongly the misfire will be felt as a rough idle and decreased power. While it’s possible that the cause of a misfire can be a fouled spark plug or a broken electrical connector, the usually-correct “when you hear hoof beats, think horses not zebras” diagnosis is that the stick coil for that cylinder is bad.

So, what are stick coils? In the early 1990s, manufacturers began to change from the old tried-and-true ignition configuration that had a single coil feeding the spark plugs at all of the cylinders, to a topology where each plug had its own ignition coil. Initially, some cars used “coil packs” where several coils were bundled together. On Mercedes V12s from 2000–12, each bank of six cylinders takes an ungainly “coil rail” that looks something like a ladder with one side missing. If you get a misfire code, you cry, because the entire rail needs to be replaced. However, over time, most manufacturers adopted a “coil-on-plug” configuration where individual coils, commonly called “stick coils” or “pencil coils” snap directly onto the tops of the spark plugs.

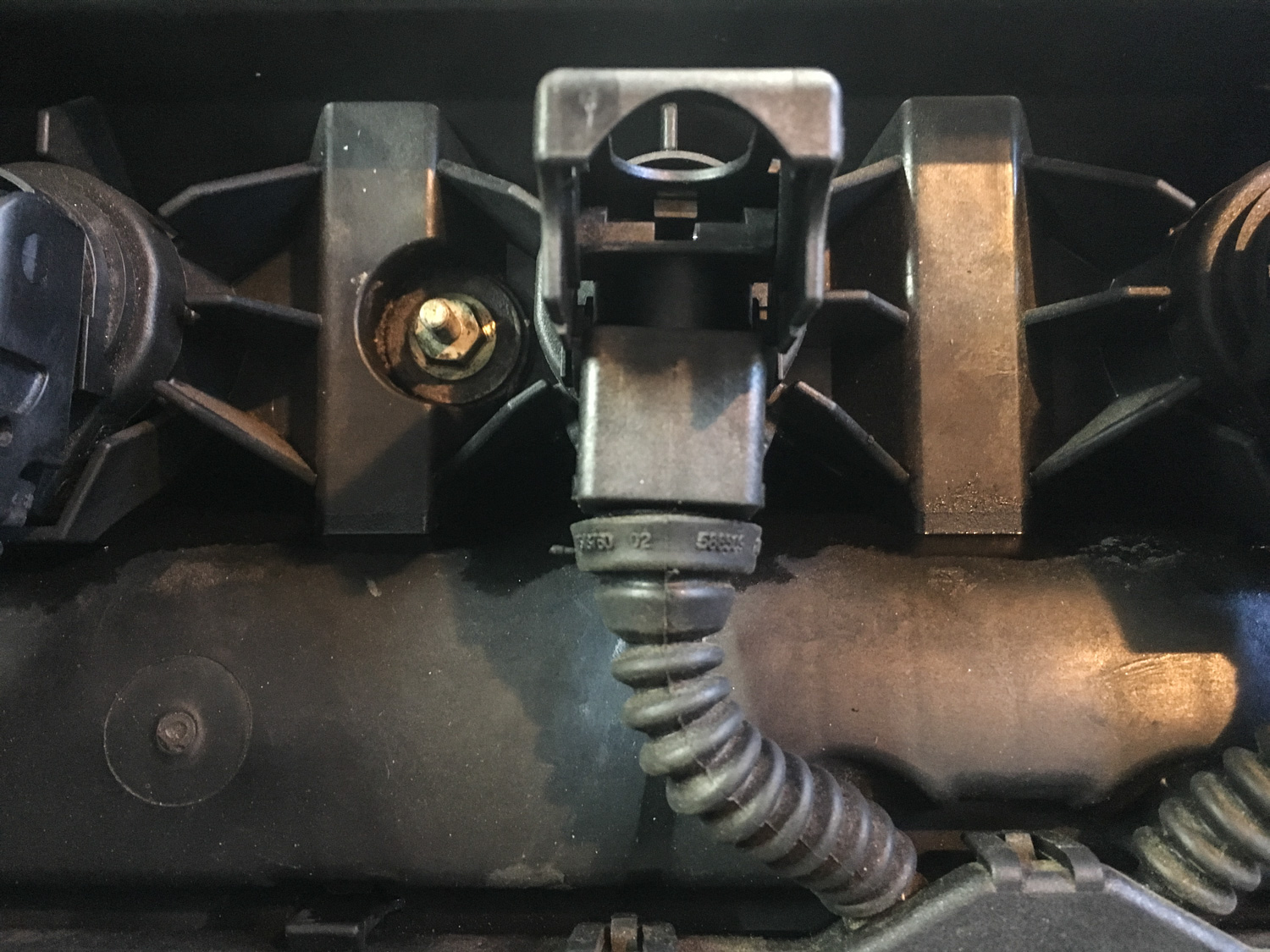

There are pluses and minuses to stick coils. The big pluses are that all of the coils are identical, interchangeable, and individually replaceable, and there is no plug wire through which voltage loss or inadvertent spark grounding can occur. But the downside is that stick coils don’t sit passively bolted to the firewall like the coil on an older car. The coils and the plugs are in recessed holes in the head, between the intake and exhaust valves. So they’re right in the middle of a lot of action. By locating the coils directly on the plugs, it puts them in a high heat and vibration environment. For this reason, stick coils do fail. Fortunately, on most non-exotic cars, they’re pretty easy to change.

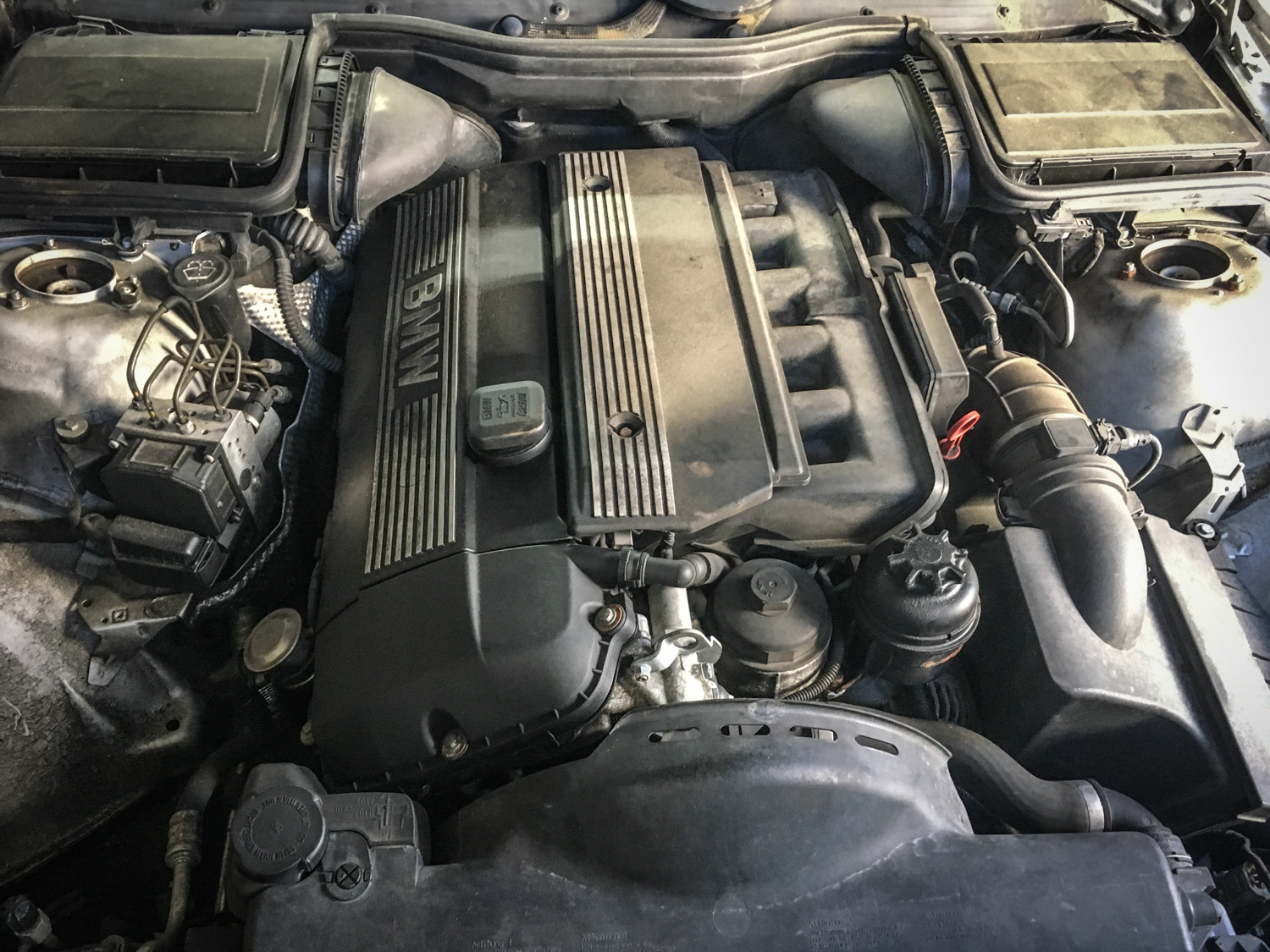

The story of my replacing a bad stick coil on my 2003 BMW E39 530i sport is fairly typical. I had a coil that was failing intermittently. Sometimes, when I’d start the car, the idle would be obviously rough, and the “Service Engine Soon” light would immediately come on. Initially, if I simply shut the car off and re-started it, the idle would smooth out and the light would extinguish, but as the weather got cold, the frequency of problem increased, and re-starting the car quit working. I connected my OBD-II code reader, turned the key to ignition, and read the codes. It was always a single misfire code (P0304), always for the same cylinder (#4). The dealer price on an OEM Delphi stick coil is about $75, but a Bosch replacement coil is only about $23.

The E39’s stick coils and spark plug configuration is also fairly typical of a modern non-exotic car. The coils are accessible once you remove the false valve cover that looks like a Sears shop vacuum. (It’s called a “false cover” because the actual valve cover with the oil seal is underneath it.)

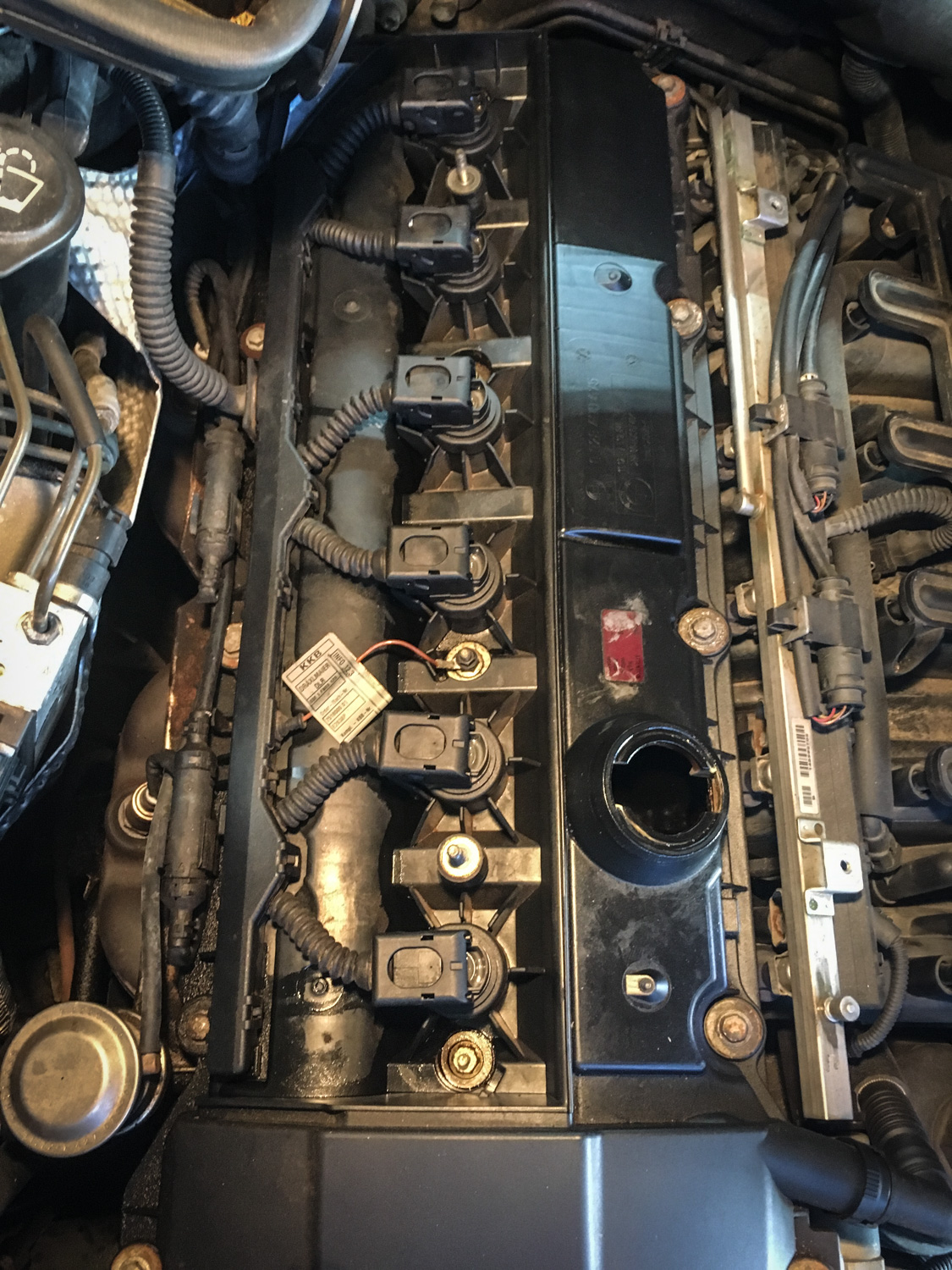

On this car, to remove the false cover, you need to first remove another cover that hides the fuel rail, and a piece of ductwork connecting the cabin filter to the firewall. After that, two trim tabs and two 10mm bolts later, the false cover is off, and the row of stick coils is exposed.

On some cars, the stick coils are secured with small bolts, but on others, including this one, a combination of a push-in rubber collar at the top of the hole, the snap-on connection where the coil attaches to the top of the plug, and the false cover itself keep the coil in place. Flip the sturdy metal latch on the electrical connector, draw out the old stick coil, install the new one, snap the connector back on, replace the covers, and you’re done. On my E39, I was in and out of it in 15 minutes.

If you want to be absolutely certain that the problem is a bad coil, you can perform a simple test as follows. Swap the misfire-code-flagged coil with the adjacent coil (for example, swap #4 with #3). Use the code reader to clear all of the codes, then start the car. If the CEL re-lights and if, when you read the codes, the misfire is still on the same cylinder (e.g., #4), then the problem isn’t the coil and could instead be a fouled plug, a broken wire, a bad terminal in the connector, or something worse. But if the misfire moves to the cylinder you’ve swapped the suspect coil into, you’ve caught it in the act. And most of the time, this is in fact what happens.

I should note that there are several things you should consider if you want to subject yourself to while-you’re-in-there-itis. If the spark plugs have never been changed, now’s a good time. And if you see a lot of oil down the recessed plug holes, it’s a sign that the valve cover gasket and its companion plug hole sealing rings need to be replaced. As far as replacing the coils themselves, typically, if I get just one misfire code, I’ll replace just that one coil, but if it’s a car I’m keeping for the long term, and if more coils begin to throw codes, I’ll replace the rest of them with the same brand as the first. But if you don’t go down any slippery slopes, and if the coil access is like it is on my E39, it really is a 15-minute job.

So let’s give OBD-II its due. It works really well for flagging bad stick coils. Remember that when you need to get the car inspected and the damn CEL is on and you pull the codes and get the dreaded “minor evaporative leak” code and it’s January and it’s freezing out and you think, “Man, this could be caused by ANYTHING. Why oh why couldn’t it just be a misfire code?”

***

Rob Siegel has been writing the column The Hack Mechanic™ for BMW CCA Roundel magazine for 30 years. His most recent book, Just Needs a Recharge: The Hack Mechanic™ Guide to Vintage Air Conditioning, is available on Amazon (as are his previous books). You can also order personally inscribed copies here.