Media | Articles

This 1-Valve-Per-Cylinder Rotary Engine Could Never Go in a Car

Internal combustion engines are a relatively new development in terms of human history. A lot of people still alive today were a part of the wild first half-century of experimentation and development that landed us at the engines and drivetrains that currently propel us so casually down the highways and byways as we go about our business. While many of the engines popular today are engineering marvels, the designs and ideas of years past can be even more interesting engineering case studies. Case in point: the Gnome Omega rotary engine.

I know some of you have already skipped to the comments to show how much smarter than me you are, but if you kept reading or have just returned after leaving said comment, thanks for the chance to explain how this is a rotary engine with pistons and valves. You are correct that significantly more well-known Wankel design rotary engines are of the “flying Dorito” type that utilizes a triangular rotor that compresses and exhausts fuel and air through passages cast into the engine block. It’s the traditional arrangement where the outside of the engine is stationary and things inside spin. Solid design, but what if you turned it all inside out?

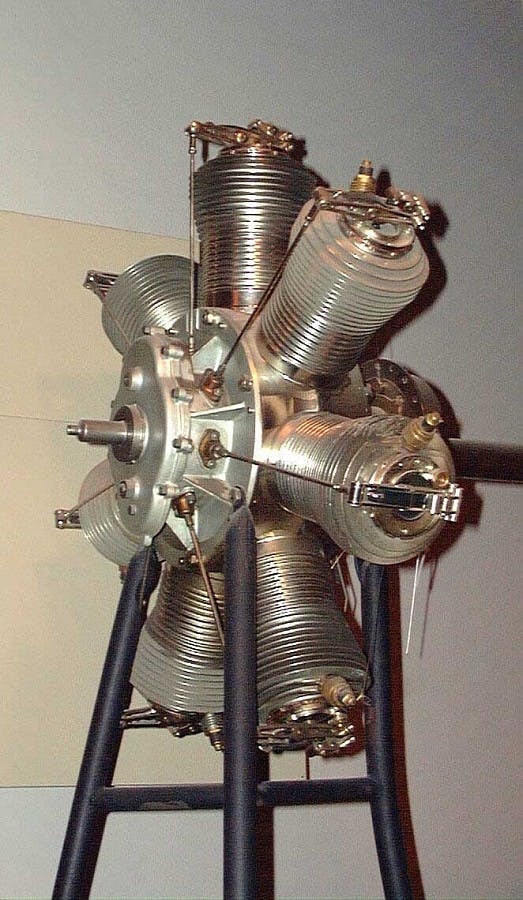

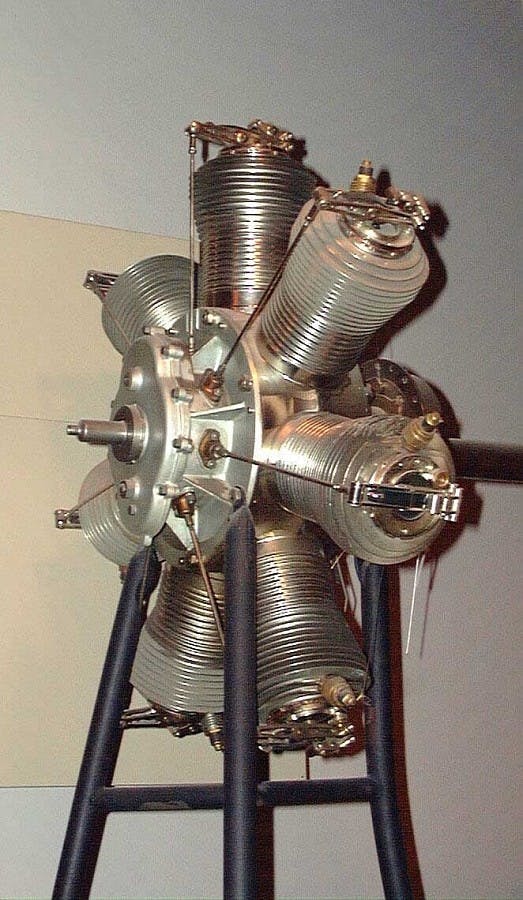

![Gnome Omega No. 1 Rotary Engine (A19990069000). [2008-13964]](https://hagerty-media-prod.imgix.net/2024/08/NASM-Gnome-rotary-engine.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&ixlib=php-3.3.0)

That’s more or less the concept behind this rotary engine. It is a “monosoupape,” or single valve, design that was mainly used for aircraft. After looking at the design it’s clear why it was never attempted for anything else. For the Gnome to make power, the crankshaft is fixed to the airframe while the entire crankcase, along with the cylinders, rotates. The crank pin for attaching the connecting rods is located slightly off center and creates the reciprocating motion. I needed to see it in motion to understand it. This video I found on YouTube was a great explainer of the system.

This means it is a reciprocating rotary engine. Yeah, weird stuff. The camshaft is also centrally located in the crankcase and still runs at 50-percent crankshaft speed but only actuates one valve per cylinder, something that even when this design was born in 1913 was either very adventurous or very curious. The single valve design works because the air and fuel enter from a port at the base of the cylinder, where a fuel nozzle sprays constantly to enrich the air as it is pulled through the hollow crankshaft and pushed into each cylinder via crankcase pressure as the whole thing rotates. Exhaust gases are pulled out through the single valve which also helps to scavenge and assist in pulling the intake charge into the cylinder.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Early designs featured attempts at speed control by throttling the amount of fuel being fed into the intake charge, but it proved largely ineffective. A similar idea attempted to alter the camshaft timing but proved too complicated. The most reliable iteration was a simple ignition cut switch that made the engines essentially an on-or-off proposition.

For all the drawbacks, the Gnome design won fans around the world. It was praised as “one of the greatest single advances in aviation” by Sir Thomas Octave Murdoch Sopwith, which is very high praise from a man whose company produced over 18,000 aircraft for the Allied forces in World War I.

The engineering and mechanical understanding required to produce an engine like this with the tools available in 1913 is amazing. This was a full five years into the mass production of the Model T Ford and most internal combustion engines were of a poppet valve design, yet it was still viable to at least attempt and refine such an interesting design. What a fascinating piece of engineering, even if it would never work if swapped into a car.

Bentley also made rotary aircraft engines, which were used in Sopwith “Camels”. Then the war ended, they figured out radial engines, and Bentley went back to making “the fastest motor lorries in Europe”

If these were four stroke engines. How was the combustion gases on the power stoke kept from igniting the fresh intake charge in the crankcase?

Some of them were two valves per cylinder, which worked well, but the one shown in this article is of the “monsoupape” variety. They did, in fact, have an intake valve, but it was internal and simply opened when the cylinder pressure dropped. So, the intake valve would open on the intake stroke, the fuel charge would enter, the pressure would increase as the piston came up on the compression stroke, closing the valve, and Bob’s your uncle (as the Brits say).

That isn’t a rotary engine (Google: Felix Wankel) it is a radial engine. Who writes this stuff???

Hi Michael. Thanks for the message. The pistonless Wankel design is just one that fits the definition of a rotary engine. The engine featured in this article fits the definition of a rotary due to the fact it has a stationary crankshaft and the entire engine case rotates. It’s uncommon compared to a Wankel but is indeed a rotary engine.