Media | Articles

Strapping my classic to a dyno might have been a bad idea

I have always been curious to put one of my vintage cars on a dynamometer to test how much power it makes. However, such a test never made sense: Most of my cars are stock, with known factory outputs, and the few that are modified aren’t tailored for true performance. Currently, the most promising candidate is my 1965 Corvair: The flat-six under the trunklid sports a mild cam, high-flow air cleaners, upgraded electronic ignition, and a custom exhaust using era-correct headers. On the right day, it really sounds the business.

But … I know where the restrictions are in this engine and what it needs to make big power. The modifications on my car likely haven’t increased horsepower by a significant amount. The epitome of all bark, no bite. So when an acquaintance purchased a house that included a garage with a chassis dynamometer, I wasn’t scrambling for a session. Bad influences—nay, friends—wore me down, and before I could make any excuses about “fragile old car,” the Corvair had a date with a psychic.

That is the role of a dynamometer. It asks your car a few questions, tests its reaction to a challenge, and reveals something about that car based on the test.

First, the challenge had to be set up properly: The Corvair’s drive tires sat between a set of rollers, and straps from ground anchors cinched down the rear from a couple of carefully selected points on the suspension. The front end was doubly secured: a strap and a chock for each wheel.

Then came the hard part: the math.

Before we had started the engine, we had a little problem. The Mustang-brand dyno installed in the my friend’s two-car shop space uses a factor to interpret the data from the load cell. That factor stems from an older metric of “horsepower at 50 mph.” The nerds call it road load coefficient: essentially, it is how much horsepower a vehicle needs to drive down a flat road at 50 mph. Mustang Dynamometer has a handy chart for most models going all the way back to … 1971. No Corvairs built after 1969.

The Corvair’s silhouette—grille-less front end, flat tail—is unlike that of most vehicles in the 1970s. Substitute models weren’t obvious. We looked at the numbers for some cars, averaged a few, and … guessed.

Why sugarcoat it? For me and the Corvair, the numbers really don’t matter. Never did, never will. I was there to learn something new and have a fun afternoon.

We did, of course, have a side bet on whether my little white coupe would crack triple digits to the tire. The over/under figure stemmed from my memory of an old forum post claiming that the Corvair’s factory rating of 140 hp typically came out to around 100 hp at the tire. I was working with a … sort-of known quantity: The engine has been upgraded, but I don’t know its mileage and have no records of who built the engine, or when, or what parts they might have used. I’ve been inside the six enough to trust that it has been rebuilt and that the person who did the job was competent. That said, it’s still a little bit of a shrug as to exactly what is inside.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

We entered our factor. Patrick, the owner of the dyno, talked me through the process: Drive up to the chosen gear and hold engine rpm at 3000. Give him a thumbs up, let off the throttle, and allow the engine to coast down to the desired start rpm. Give another thumbs up and, once Patrick returned the signal, mat the throttle.

The noise. The vibration. This subtle sensation of speed—burying my right foot, hearing the engine on song—sat right next to a feeling of calm: The only thing moving was the tachometer needle, which rose with all the speed of an octogenarian filling a buffet plate.

Right as the tachometer needle touched 5000 it was time to lift, put in the clutch, and let the dyno spin down a bit before lightly helping with the final slowdown using the Corvair’s brakes. Letting off the throttle was met with a big pop as flame shot out of the exhaust.

The cacophony of noise, vibration, and anticipation began to mellow. I was immediately proud of the car—nothing had exited the engine except a massive backfire when I closed the throttle. After letting the engine idle for a minute, we shut the car off. I got out, and we surrounded the dusty computer screen to see what the psychic had to say.

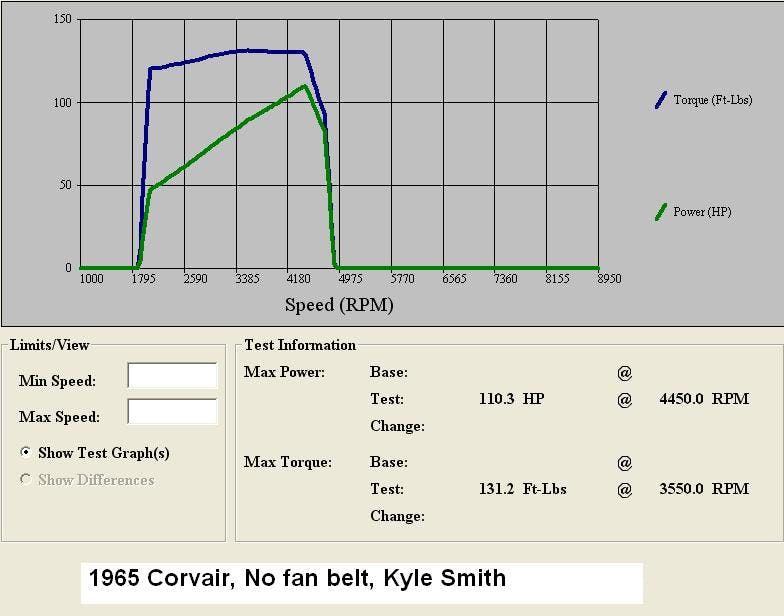

96 horsepower and 120 foot-pounds of torque. Not too shabby. 96 was in the ballpark, given that the original, 140-hp rating for this engine was measured in gross horsepower: The tests were done utilizing an engine, not a chassis, dyno and an engine from which most of the accessory drive had been removed. For the Corvair, the accessory drive is literally just the alternator, but the crank-horsepower figure is optimistic considering that many more components are needed to turn crankshaft rotation into forward motion. The transmission, differential, and other necessary accouterment all soak up a little power. Over the years I have heard drivetrain loss is in the 15 percent range for manual-transmission cars, but that “rule” is misleading at best. It’s hardly a rule, more of a generalization if anything. Being “down” 32 percent compared to the factory rating is actually not bad considering everything that can and should be factored in.

The peanut gallery checked my initial feeling of smug: At higher rpm, a screen of black smoke had poured out of the exhaust pipe—unburned fuel. Confusing, because when I went through and cleaned the carburetors years ago, I could tell there was no funny business inside. Jets were stock sizes, no evidence of machining. While their lack of modifications didn’t explain the smoke, it likely explained why the torque levels off and begins to drive down as rpm increased. What a lovely, flat torque curve.

Since we knew the car wouldn’t explode under the stress of the dyno, we decided to have some fun and take off the fan belt. The Corvair’s is an air-cooled engine: A bi-planar fan belt turns a magnesium fan that forces air down through the finned cylinders and cylinder heads. The system is critical to keeping a Corvair engine alive during regular use, but driving the fan sucks up a ton of horsepower. Your engine doesn’t even have to be air-cooled for you to observe the output difference with and without the fan: Plenty of people with access to dynos have tested flex fans versus electric fans on small-block V-8s.

After letting the big air-mover fans blow down the fan intake for a bit to cool things off as best we could, I popped the spring-loaded belt tensioner in and zip-tied the belt to the oil filter adapter to keep it from catching on the crank pulley during the dyno run. A clean pull felt a good bit spicier and the results revealed all those forum posts from armchair engineers (and real engineers) were pretty well spot-on.

Did I need to know these numbers? Of course not. And if I did, our method would have been a terrible way to discover them. Still, I got the opportunity to test my car in a safe, controlled environment. In just a few hours I learned the Corvair was running rich in the higher rpm range, something I likely would have never learned just driving around town. As I drove home, I thought about how to fix the fueling issues and debated with myself about plopping down the money for a modern cooling fan. Do I need it? No, but I now know what could be, and the prospect sure felt fun.

That psychic inside the dyno computer says the same thing to everyone and is also always right: You can make more power if you want. How much do you want to spend?

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Interesting stuff, thanks for giving it a try.

And thanks for providing images of the results. I’ve found that a LOT of people who dyno their cars tend to fudge the numbers to impress their audience. How many cars with 384 horses are claimed to have “500” at the bench races? 😃

It’s funny, most folks used to say 400 hp, or 450. My first build was 409hp. Not being nostalgic, that’s what it was after an average of 3 pulls on an engine dyno. When Id tell folks and all that was in it, invariably someone would 1 up and say oh well, my (brand) is 425hp. Rather than debate the merits of their stock heads, smaller cam, low grade intake and edelbrock carb, I just smile and nod.

First chassis dyno with a nailhead Buick – just barely over 200 to the ground. I spent way too much time trying to get there.

Also why I don’t give specifics. Now I just give an approximate. Folks will do the nod and the smile, and that’s fine.

Still, any output is a bench mark. Use it!

There are a couple in my collection that I wouldn’t mind putting on a dyno. My 74 Vette is a 454 clone. The block casting number is right for a Corvette 454, and it has a mild cam, but that’s all I really know about the engine. I have a git-r-dun level of tune on the carb, but I’ve never really took it down to a good stretch of empty road and dialed it in. It’ll put you back in the seat pretty good, but I have always been curious to see if it breaks the 300 mark. My 65 Impala is currently powered by Mercruiser… which essentially amounts to a 90s era truck 350 with brass freeze plugs and a marine cam. Kind of curious to see what that would do on the dyno. My money says it will put out more power (but less torque) than the Vette… maybe one day I will run across someone with a dyno

Keep in mind the 140 hp was gross hp not net as you were testing. So you may really have a good number at 96.

Cool article and thanks for doing it with your Corvair!

Great article! I am motivated to try the same on my LeMans.

When I did my first engine rebuild (455 in a ’66 LeMans/GTO clone), I had it put on an engine dyno, and the first thing the guy asked me is was I happy with the numbers we got. I was just happy to know what the numbers were – I wasn’t hoping for any specific targets. Then, after my second rebuild (long story, related elsewhere on this site), I decided to do a chassis dyno test, as really, what does flywheel HP do for me – I want to know the numbers at the wheels (more relevant, I think). The first thing the operator said was, “so, are you good with those results?”

Apparently, dyno guys are used to customers demanding that they are getting gypped on the numbers and demanding higher, more powerful data. My point (or suggestion, really) is that you should know what it is you’re looking to get out of a dyno session before shelling out cash for one. Kyle found out something he wasn’t even anticipating, and to his credit, that seems like a more important string to follow than being concerned about the hp and torque questions. He might actually discover some improvements to make to his carb tuning that won’t even affect those numbers. If you’re looking for bragging rights, though, be prepared for either good news – or not-so-good – before you go. Be realistic about what you want to know and why!

Always loved that generation of the Corvair.

Sniper EFI!!

Could be interesting. Would have a lot to figure out though. Making EFI play nice with the Corvair intake design and also scaling the water temp input to work with cylinder head temp are just two of the main ones. Totally solvable, but I like my carbs for now.

I’ve always loved these Corvairs, but my only experiences were with a HS friend who wanted to spin the “frozen” fan while I was setting his timing (strobe effect, donchakno) on a ’69 Corsa, and an acquaintance that had a 327 SBC/transaxle V8 conversion in a ’67 Monza (squirrelly doesn’t come close). My dad worked at the Delco Remy plant in Anderson IN all his life, and Mom had a bathtub ‘vair, but I was preschool and don’t remember anything save it was blue and got rear-ended when I was 4. I really like your wheel choice, although I am partial to AR Torq-Thrusts on pretty much everything.

Perhaps, instead of the FI thing, with the manifold and sensor hassles, you might consider the 3v Weber or Del’Orto carbs as used on the earlier 911 models? Certainly a competent machine shop could fab up the manifolds, and the linkage I suspect could be adapted from an aftermarket 911 set, both being flat 6s of similar dimension. Porsche has a huge aftermarket support net, so everything but the manifolds would be easily obtained- $pendy, but easy.

Looking forward to more Corvair adventures!

Was the air/fuel sensor a help in setting up the primary carb on each side? What can you do to lean the mixture at high RPMs when the secondaries kick in?

Smaller jets in the secondary carbs would have an effect on overall fueling at higher RPM. Personally I think something else is wrong because given the modifications and engien setup it should be lean if anything, not rich. Will be fun to dig into.

Great seeing the Corvair Dyno Test. I had 5 of the second generation cars back in the late 70’s and 80’s. Some running, some for parts. Those 140 motors with 4 Single Rochesters were mechanical secondaries as I recall. Yes, they would dump gas until the rev’s got up. The 140’s were easy to overload with fuel especially when going up steep inclines in 4th. My favorite was a 69 110. Not as fast as the 140’s but a sweet power curve in a fun to drive car.

It was that cool distributor and hot red spark plug wires that got you all the Horsepower!

When something works, it works! Thanks for coming to read the story Seth!

I have the new NASH fan on my Corvair 4-door so Haha.. 5 more HP to the wheels or .25 more MPG!

Oh how I have been tempted to reach out to Kevin and swipe my card for one of his fans. One day. Hopefully soon.

Yes, I’m over a year late. I noticed that Matt from Matt’s Off Road Recovery has one of those fans. He hasn’t said anything about it, tho. I live in Phoenix AND my 65 Monza has factory A/C, so, it wants to run hot. No Idea how expensive those fans are tho.

Please check with 289thunderhead on YouTube about fuel return system and how it steadies the carb fuel input pressure, might just you need!

I scrolled through that channel and didn’t see any videos on a fuel return. My Corvair has an electric fuel pump and a fuel pressure regulator (set to a float-friendly 4psi) so pressure should be consistent regardless of rpm but checking fuel pressure is not the worst idea. I’ll have to snag a gauge and hook it up.

Here is the Fuel Return line video from Thunderhead289.

https://youtu.be/pTg3BP0-SVE?si=w5iJ8MOrR9thZmYi

After watching that video I’m not particularly sold on adding a fuel return line to be honest. The main thing I see is the introduction of more potential leaks or failure points. He even points out that all the rubber fuel lines in his engine compartment are unsafe and a bad idea but then schluffs that off with the old “but I haven’t caught fire yet” which is not a great way to view safety. In the Corvair rubber lines are even more dangerous due to the chance that the fan belt with be thrown and rip a rubber line and start an engine fire.

Also, he seems to be forgetting that the carb is not drawing off the fuel line, it is drawing off the float bowl. Very consistent line pressure would not affect the engine running because the fuel in the float bowl is all that matters, and that is at atmosphere pressure regardless of what the pump might be pushing. The needle and seat closes off the fuel feed. While he has a point about fuel temperature being cooler for awhile, eventually all of his fuel is getting heated by the engine compartment since it all circulates through that hot environment rather than staying in the tank. In a mild engine like my Corvair I fail to see how a return fuel line setup would do anything other than add complication and failure points.

Would be interesting to see what your Model A is putting out.

I’m not sure the Model A would even get the rollers turning!

I’ve watched enough dyno fail videos to feel any pull that results in no damage is a good run. If you go back, you might verify the throttles are really opening all the way. Most linkages are set up so the pedal hits the mat before the throttles hit the stops to prevent damaging them. Some adjusting might be worth a few ponies if you can use a gentle foot.

My first car was a trashed 1965 Corvair with a 1963 (smaller 95HP) motor in it. Dad taught HVAC at the local trade college at night, so we had access to their dyno. This car had tiny air filters on each of the two carburetors, headers and glass packs (remember them?).

It managed 60HP on the dyno. Dad had me remove the tiny JC Whitney air filters and it jumped to 70HP.

Not bad for a worn out engine rated at 95 horses.