Media | Articles

Slowly but surely, my dueling 850s will be reborn

It made perfect sense at the time. I’d yank out the Mini’s seized engine (along with the transmission bolted to the bottom of it), install the replacement drivetrain that’s been sitting in my garage for months on end, hook it all up, and I’d have a running car by the end of the weekend. Shift linkage issues punctured the thin membrane of optimism that surrounded this project, and the car is still perched a foot and a half in the air, buried under a pile of its own parts, with a gaping emptiness in its engine bay.

Shambolic setbacks aren’t unusual in the Ministry of Rust, but this one was entirely my fault. It’s the first time I’m venturing into the Mini’s cosmos, so I learn something every time I turn a wrench. What I didn’t know—but, admittedly, should have spent at least a few minutes looking into—when I bought the spare drivetrain was that there were three types of shift linkages used and they’re not easily interchangeable. My car is equipped with what British car worshippers know (and fear) as a magic wand. It looks like a bent broomstick that juts out from the transmission through a hole next to the gas pedal. There was also a more conventional remote shifter with a small gear selector between the front seats and linkage parts under the body, plus a simpler rod change shifter fitted to later cars until the original Mini retired in 2000.

The engine I bought came out of a 1972 Mini like mine, and it’s identical (848-cc) to the one my car was built with, but its transmission is set up for a remote shifter. I didn’t realize this until I had pulled the original drivetrain out and dropped it onto a luggage cart that I, rather ingeniously, pilfered from a local airport for the occasion. I had two options: I could drill a few holes through the car’s floor, install a remote shifter, and keep the transmission that came with the engine, or I could put the car’s original gearbox under the new engine and keep the magic wand. Either way, I was missing parts. And, regardless, the car wasn’t going to move under its own power by the end of the weekend. Score one for the Mini, then.

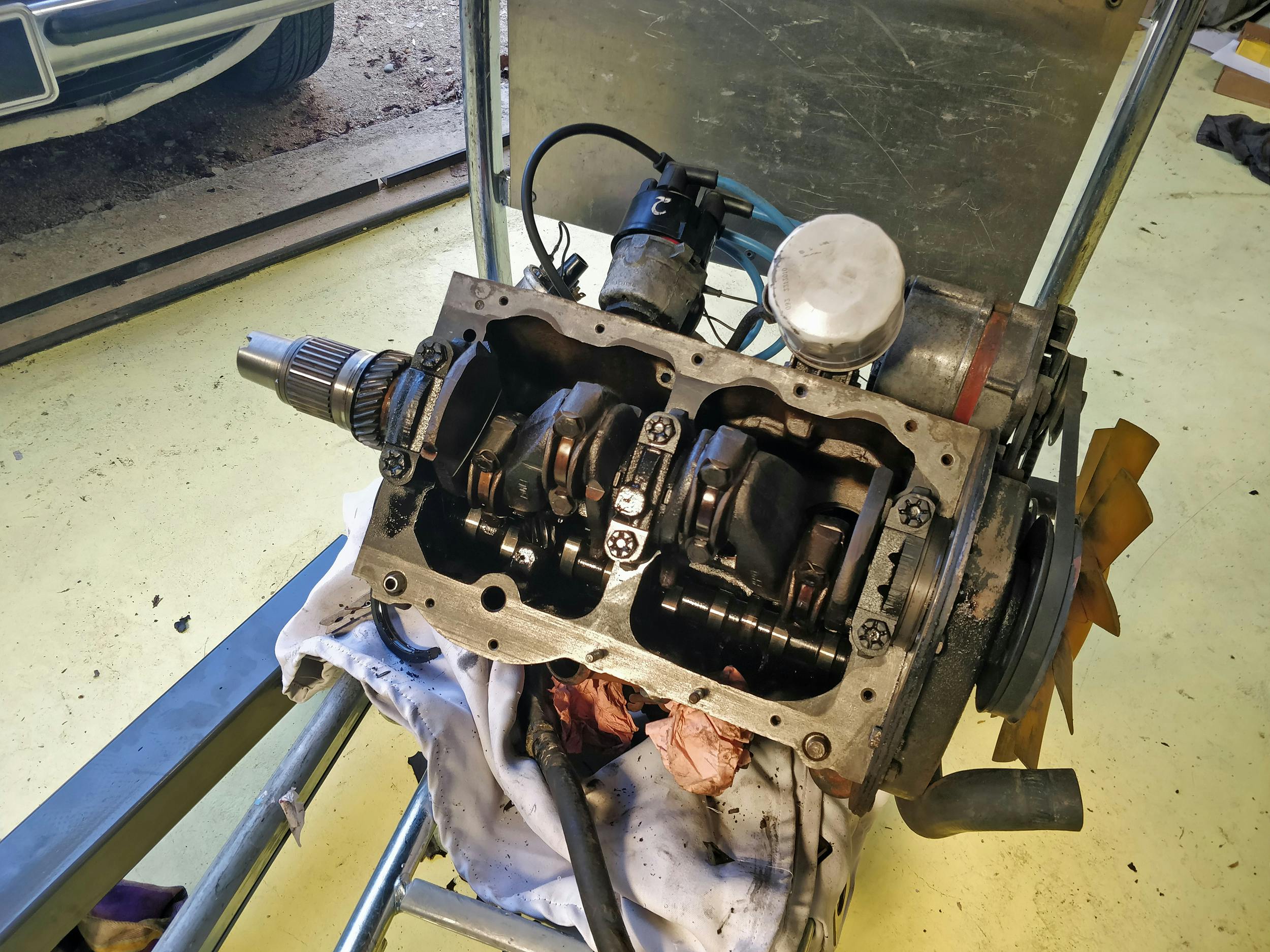

I quickly ruled out the remote route in the name of originality, somewhat ironically, so I started disassembling both drivetrains. It’s no different than taking off an oil pan; about a dozen nuts and bolts secure the transmission to the engine, and removing the old gasket requires hours of careful scraping. I decided to change as many seals and gaskets as possible before making one drivetrain out of the two, which inevitably delayed the project. I’m an oil seal and a bellhousing gasket away from calling it done. I’ll then install a new clutch, bolt the flywheel back on, and seal it all up. It should be straightforward from here on out, but so would taking an angle grinder to damned thing and turning it into a desk.

I’m kidding. Mostly.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

From one 850 to the next

As the Mini and I exchanged death stares, the 1971 Fiat 850 was doing an admirable job of clawing its way out of the Ministry of Rust and morphing into something I’ll soon be able to drive around. Progress on this project has been much more linear, and it moved under its own power for the first time in 17 years.

On paper, these are very similar cases: both are small economy cars manufactured a year apart and ultimately left for dead. In reality, there is one key difference: the Mini needs to be resurrected, while the Fiat simply asked to be gently woken up. I’ve methodically gone through each system one at a time and replaced every wear-and-tear part in it. Ignition? Check. Fuel delivery? Done. Electrical? Good to go. Brakes? Yep, but finding the correct brake lines became weeks-long nightmare.

Lines advertised for the 850 ended up being either way too short or far too long. It was in the middle of a frustrating, hot-tempered phone conversation with a Paris-area parts vendor that I decided taking the 850 for its first spin since 2003 didn’t require brakes. All I needed was a flat enough field, which I conveniently have access to via a private dirt road. So, with my nerves in a highly-strung state, I backed it out of the garage – hand on the emergency brake – and pointed its little nose down my driveway.

I’m not exaggerating when I say it had no brakes; the steel lines were off the car. With that said, and before you leave angry comments, keep in mind I stayed on private property where the worst that could have happened was plowing into old hay bales twice the car’s size. First gear in, clutch out, and the Fiat lurched forward as its four-cylinder sang a raspy yet melodious tune. Only the Italians could make a city car sound this good. Clutch in, second gear, clutch out, and the 850 became the self-appointed king of the dirt road. I briefly engaged third gear before steering into the aforementioned field to turn the 850 around. No hay bales were hurt, the car’s maiden voyage was a success, and it left a fantastic first impression. The engine revs and idles well, the clutch feels great, the shift linkage is solid, and there’s no play in the steering, which was a stellar surprise as these steering systems tend to feel increasingly like cotton candy as they age.

My palpable excitement cooled when, after a couple of trips to the field, I smelled that the 847-cc runs hotter than it should. I haven’t fully gone through the cooling system yet—it’s the next bullet point on my to-do list—so the whiffs of coolant that shot up my nose weren’t a complete surprise. I suspect the thermostat isn’t opening all the way, though that’s just a hunch I’ll need to verify. The brakes are back in one piece as you read this so, once the cooling system is sorted, I’ll turn my attention to the suspension, install a new set of tires, and, at long last, make an appointment for a safety and emissions test.

The road is ours after that. The idea of hopping over the mountains to Turin, where it was built, occasionally crosses my mind. What are the odds Fiat will let me take it on its rooftop test track?