Media | Articles

Moskvich Update: Missing parts—and found motivation!

Ahh, procrastination. My last Moskvich update was posted nearly a year ago. I was embarrassed when I realized that this morning as I was deciding whether to go out in the cold to work on it. Has the progress really been slower than the car itself? Yes, but for mostly good reasons. Hop in for paragraphs full of excuses!

Last time we discussed my Soviet survivor, I was under a perilously suspended hulk while a deluge of rusty water and pig pen mud rained into my orifices. That’s what happens when you steam-clean the underside of an over-50-year dormant 1958 Moskvich 407. After my ear infection had gone away, I was able to take stock of what metal was left, as well as define a vision for the car. I decided that it should be like a grilled cheese; crispy and toasted on the outside, smooth and shiny on the inside. Make the mechanical bits work better than new and prep the underside to fearlessly plow through mud, salt, and snow. Change the interior and exterior absolutely as minimally as possible. With this in mind, the structural rebuild was first priority, followed by aggressive parts procurement. And let’s not forget rampant disorganization.

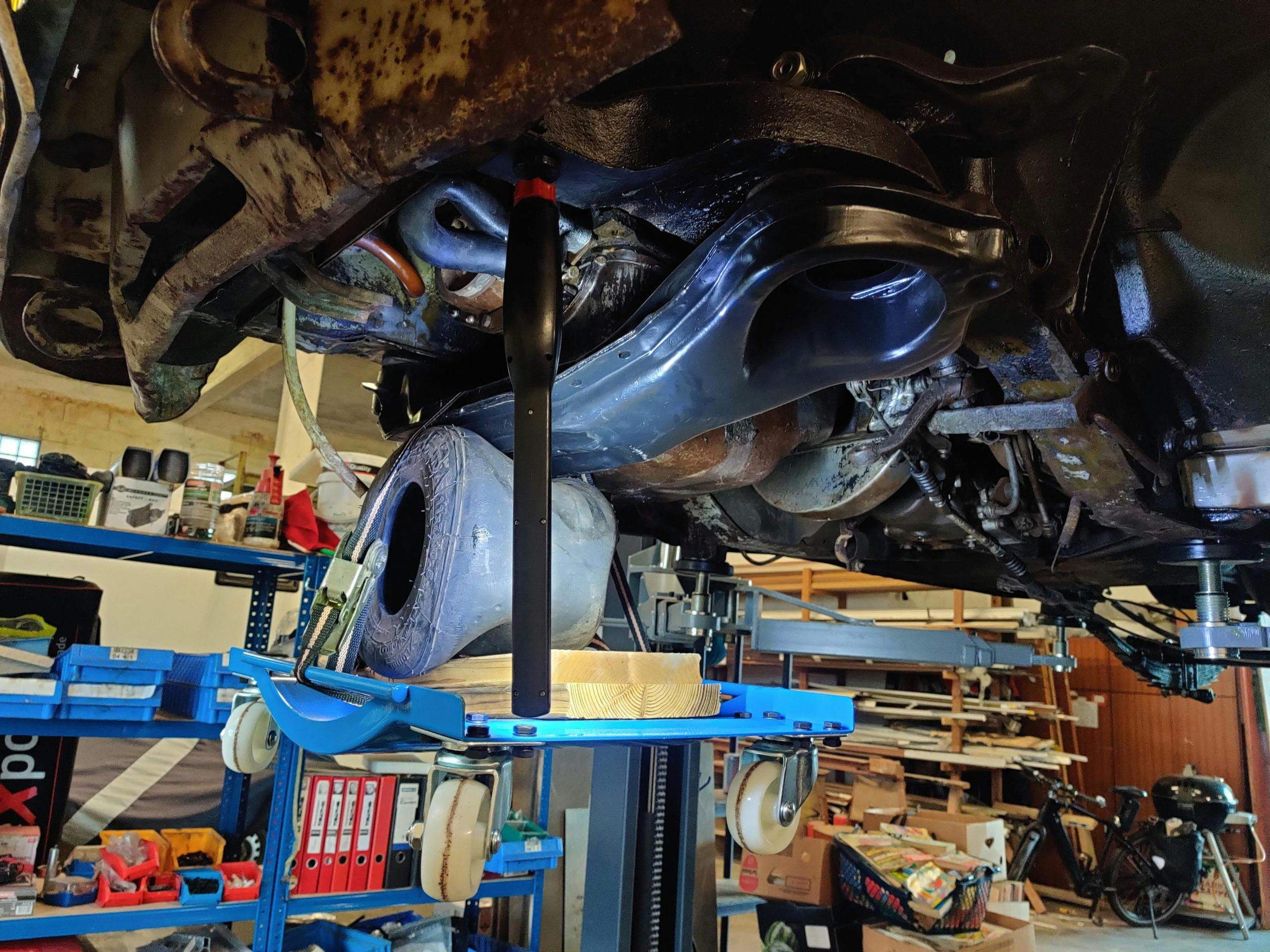

Upon putting the car on the lift, I quickly noted that the jack points were working more as, ah, crumple zones for the lift arms. Three of the four lift points crunched under the modest weight of the Moski. Making new pedestals from scratch would take more time than I had planned. But wait a second! Using slush and rock salt as a jeeper creeper, I slid under my Lada Niva and noted a similar style weld-in jack point. After quick look online, I had a shopping cart full of four new Niva pedestals to the tune of about $40. The Niva units were a few inches taller than the Moski versions, but that was quickly rectified with some cutting, heating, and bending. The rear required replacing a small portion of the floor and inner rocker but it all came together like a matrioshka (Russian doll).

The front, well, that’s a sadder story. The entire footwell, inner and outer rocker, frame, and jack point were suspended in a brittle constellation of paint and tar. I made a few “measurements” and a template using the lid of a shoe box. The last couple of holding spot welds were drilled out and I laid waste to the whole 1-square-foot area with a hammer and chisel.

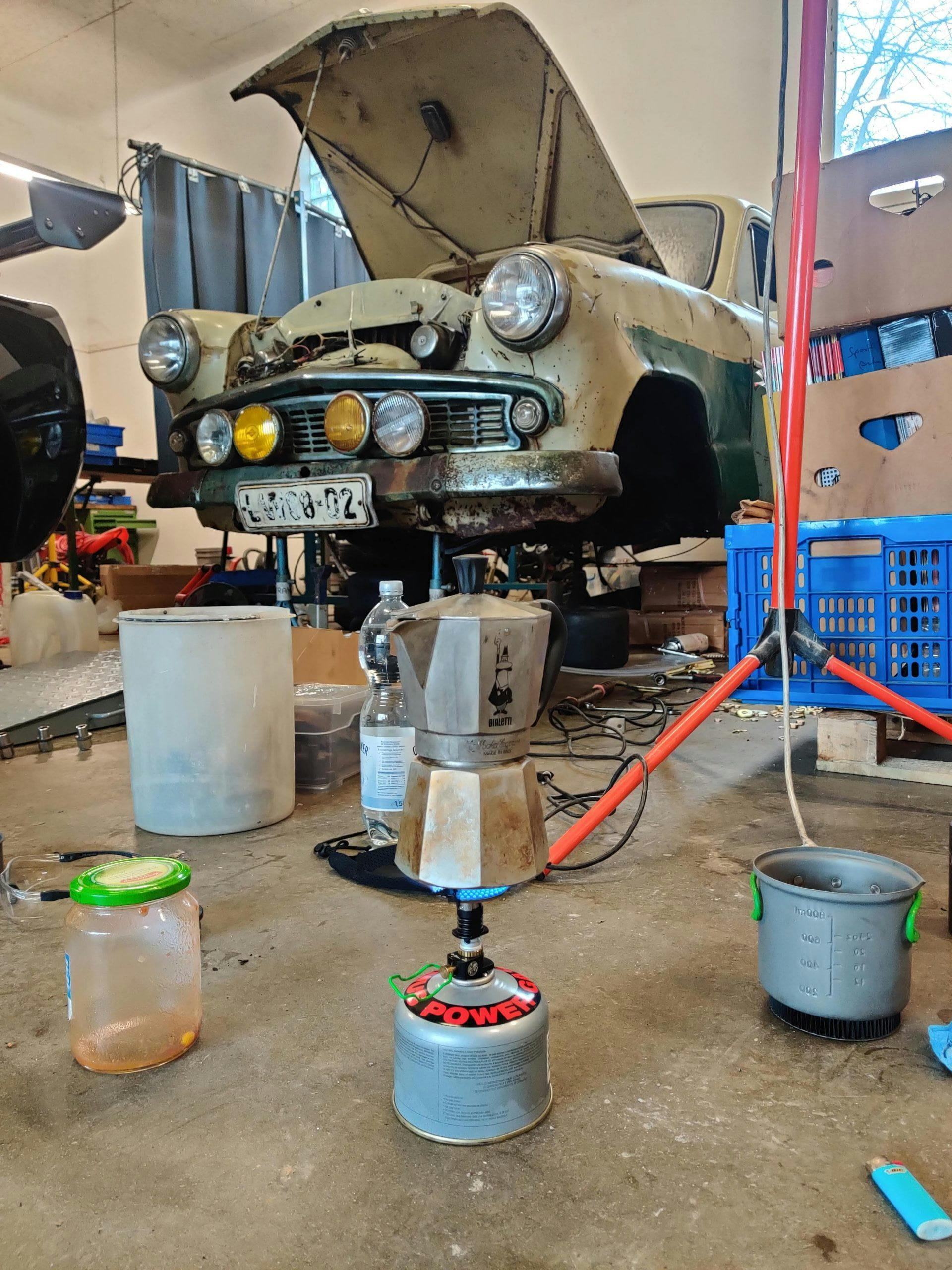

Now, on to the fun part: trying to remember what it looked like beforehand. After a few evenings in the shop, the basic structure was bent, rolled, hammered, and welded into place. And I only managed to catch the wiring harness on fire once! Considering I ran out of shielding gas during lockdown here in Germany, and much of the job was done with flux core wire, this was an authentic exercise in austerity suitable to the character of this Soviet car. It was the most complicated job I’ve attempted in poor conditions, but it turned out fine.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Rotten structure would prove to be nothing in comparison to my next battle: replacing hard-to-find parts in the front steering knuckles. It all started when I noticed my kingpins—which don’t float, they’re pressed into the knuckle—were beyond trashed. Usually there is nothing to it. Step 1: Pound or press out the old ones. Step 2: Buy new ones. Step 3: Ream fresh bushings and pop the new jobbers in. Done. In none of my previous jobs was there a Step 1.5: Paying a third party to peruse Lithuanian flea markets.

But nevertheless, here we are. All Moskvich kingpins die the same horrible death brought on by generally odd suspension design.

Trigger warning: Non-nerds, please skip this lesson in Moskvich 407 suspension. The 407 uses an short-arm-long-arm setup with a knuckle joining the two. I can only speculate why they did this, but the inboard mounts for the upper control arm are not bushings, but ACME thread. (Like what’s used on a lathe bed.) In fact, in the exploded diagram below, parts 6, 12, 26, 30, 31, 41, and 45 are all threaded. What would ordinarily be a lower ball joint is a system comprised of two concentric sets of ACME threads connecting the control arms to the knuckle via a kingpin. When the suspension goes into bump, all of those components allow rotational movement of the suspension components via their threaded connections screwing in and out of one another. It’s beautiful, but complicated. Oh, and all of that needs to float on a layer of fat or all of the threaded areas will interact and grind themselves smooth. Only two grease fittings and a complicated network of passages are responsible for keeping that entire get-up from eating itself. In my case, every single interface was packed with mud meaning it was all scrap. Yay!

Finding parts was no problem. Finding good parts and proper parts is like pencil diving to the bottom of Lake Baikal. I was able to piece together half of the parts from several different online Soviet parts retailers. Of the pieces I ordered, only a fraction were correct for the car. I’ll chalk this up to my own impatience in cross-referencing and of course not speaking Russian. At this stage, I had everything but the kingpins and all the parts with the weird threaded interfaces. Remembering a previous purchase of a Soviet-era roof rack and some books from a particularly helpful dude in Lithuania, I remembered I had a contact. He was able to hit a swap meet in Kaunus for me and mail me the threaded parts. Score! Well, until they arrived. Half of the parts had the same ailment as mine and went straight in the bin. A further footnote: I sent another helpful Lithuanian enthusiast to yet another market in the city of Vilnius; he confirmed there were also none there. So much for Lithuania.

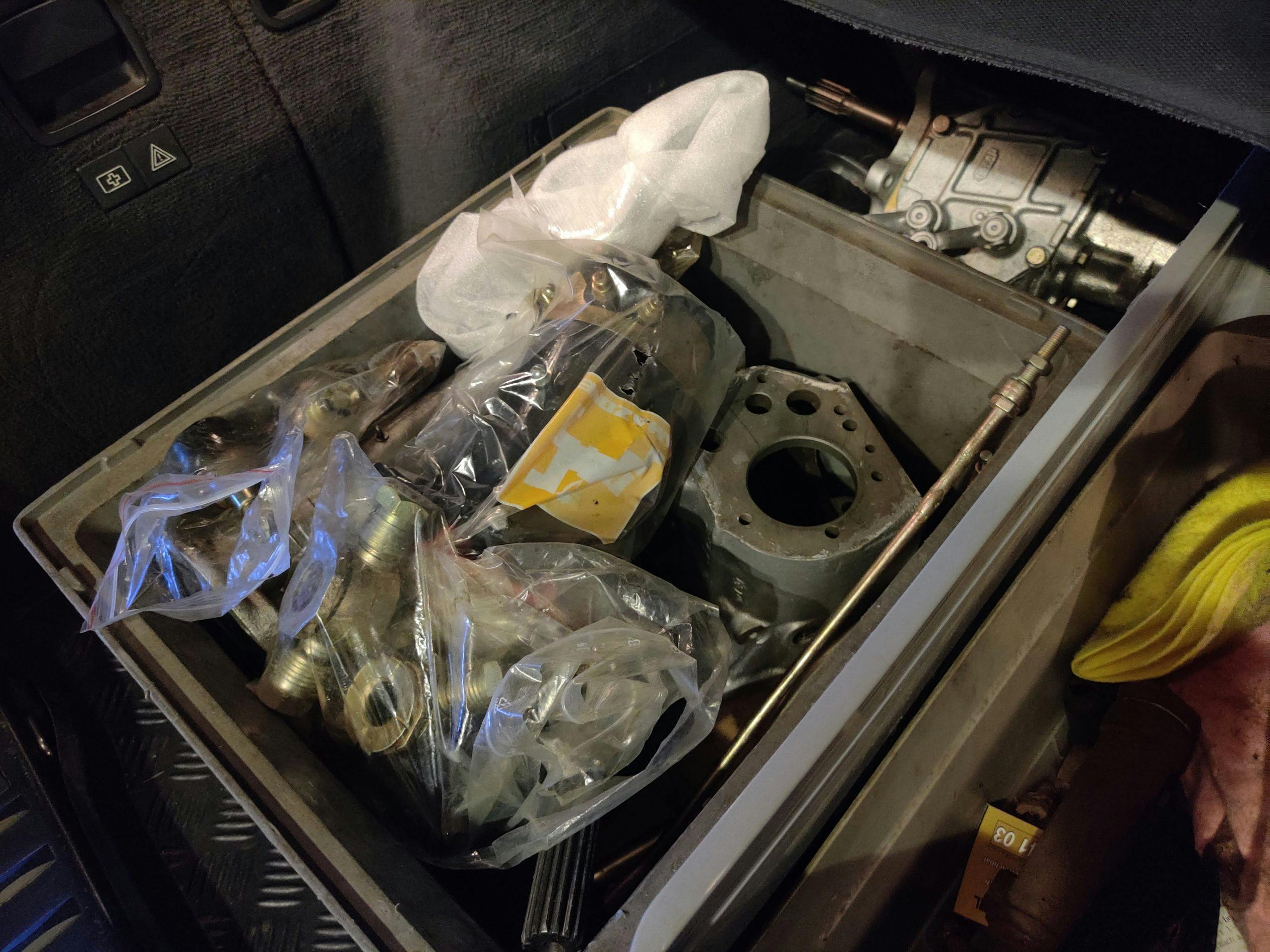

A few months later, I noticed a picture of a pile of basically all these missing pieces, on eBay Kleinanzeigen (like Craigslist), and agreed to meet the seller five hours away in Hanover. I drove up after work, booked a hotel, and met the guy: a transplant from Kazakhstan who brought his Moski and spare parts from Karagandy to cruise through his collection. Sheds fully of perfectly organized NOS parts awaited my picking. But the uprights and kingpins I came for? Inexplicably scrapped.

This long story ends with me binge eating pizza alone at an Italian restaurant, wondering how I just drove all evening on the false promise of good uprights. All just to fill my 3 Series BMW wagon full of parts I didn’t really need, while the ones I actually did need would have fit neatly in small flat-rate postage box for $4. At this stage, I had already commissioned my local restoration shop to make a pair of kingpins months ago. Busy with contracts with the King of Thailand and the Mercedes Benz museum, he understandably hadn’t gotten to it, so I cancelled my order. Still no solution.

As luck would have it, I posted a picture on Instagram with a #moskvich407 hashtag and someone I didn’t know “liked” it. I did a bit of stalking and he had a few pictures of freshly machined kingpins in his feed! What?! He rang up his machine shop and ran off another set for me at cost. What a legend! And when it rains, it pours. In the same day, I found an old warehouse inventory in the Ukraine with a complete set of new uprights. Now, both sets are on their way to me. (After such a drought I might as well put a set away.) For relaxation and a sense of job completion, the control arms and integrated sway bar mounts were all bolted together.

In other news, after an evening of grilling and frosty beverages, a buddy of mine and I got the old girl running with some sanding of the points, a battery from my Skoda Favorit, and a can of brake cleaner. I do have an engine gasket set but should probably stock up on all the other motor bits for an eventual rebuild. Or maybe swap that Soviet M10 copy in at a later date.

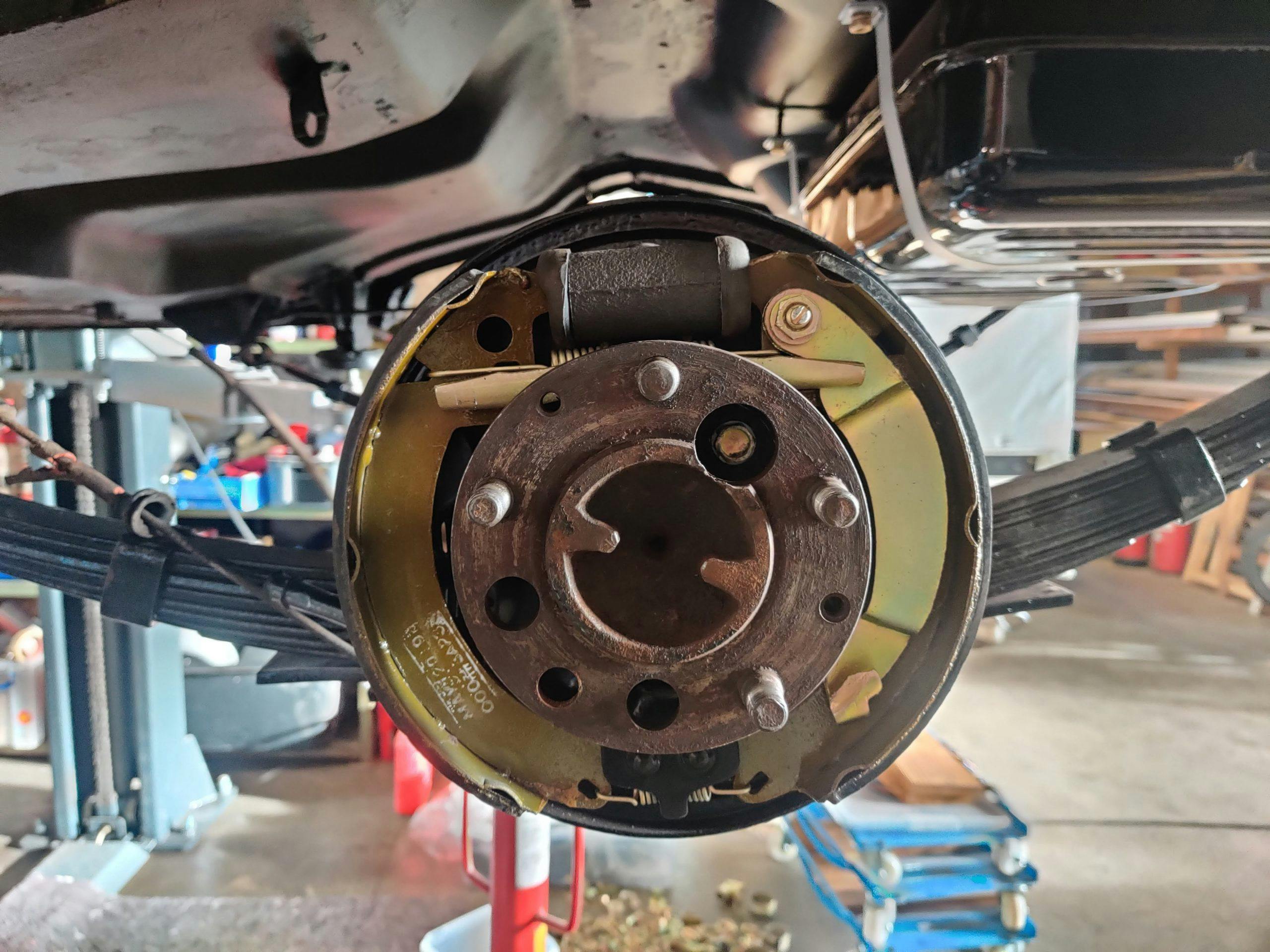

So, in the past two weeks I’ve been burning my hair with weld spatter, shooting sparks up my sleeve, and occasionally bolting new parts on the car. What’s the status now? The rear axle is coated, rebuilt and back in with new leaf spring bushings, the rear drum hardware is all zinc’d and back together, the gas tank is back in with freshly soldered brass gauze on the pickup and rebuilt sender, and the entire front suspension minus uprights is back up under it. Tomorrow I’ll run some new copper-nickel brake and fuel lines and send a follow up email to check on my master cylinder rebuild kit that’s stuck in customs.

Though there were major moment of procrastination, mainly brought on by tiresome parts procurement stories, I did manage to get a fair bit done. However, the time laziness is over. For real. The sun is setting on my time here in Europe, which means this weird thing has to be ready to board a ship for Charleston, South Carolina in about five months. Wow, just typing that freaks me out. Rest assured, there will be more Moskvich updates coming, from both Europe and America!

***

Matthew Anderson is an American engineer who relocated to Germany a few years ago for work. In his spare time, with reckless abandon, he pursues a baffling obsession with unexceptional Eastern Bloc cars. We don’t ask him too many follow-up questions.