Media | Articles

Mix Master: After 120 Years, the Carburetor Still Befuddles

To work on carburetors requires, first and foremost, a sense of humility. More than a century after their invention and some 30 years since their disappearance from new production vehicles, these intricate analog computers continue to bedevil even the mechanically inclined.

Yet all carburetors, from the one on a two-stroke weed whacker to the six Webers on a Ferrari 250 GTO, have the same core components and operate via the same principles. Understanding these fundamentals can help you tune your own carburetors or, at the very least, help you appreciate them.

An internal combustion engine, no matter how rudimentary or sophisticated, can only run properly if the liquid fuel in the tank is converted to gaseous vapor before it goes into the cylinder, and if the air and vapor are mixed in the correct ratio. To complicate matters, this ratio varies widely with operating conditions. During startup, the appropriate ratio is 8 pounds of air per pound of fuel. For peak cruising efficiency, twice the amount of air—16 pounds—must be metered for each pound of fuel. During acceleration, the ratio will momentarily drop to 9:1. Getting the ratios wrong by even a little—too much fuel and the engine is said to be running “rich,” too little and it’s running “lean”—causes problems.

Early History

Patents issued throughout the 19th century attest to repeated attempts to address these challenges. They generally proscribed a vessel containing fuel that intake air would skim across. The first device we’d recognize as a carburetor debuted, not coincidentally, on the first small high-speed internal combustion engine to run on gasoline, which was patented by Wilhelm Maybach and Gottlieb Daimler in 1885.

In 1899, brothers George and Earl Holley founded a carburetor-manufacturing enterprise in Bradford, Pennsylvania, later moving to Detroit to supply Henry Ford and other carmakers. By 1913, half of the autos produced in the United States were equipped with Holley carburetors.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The Physics

The “magic” at work in any carburetor is Bernoulli’s principle, which states that air pressure varies with the speed of its flow. Swiss physicist Daniel Bernoulli came to the idea by watching water flow in a river. At wide spots, the water slowed down, while at choke points, it sped up, meaning that speed and pressure were related. He published this theory in 1738. Aircraft employ the principle to produce differential pressures on their airfoils—higher below, lower above each wing—yielding lift. As with a river pinch point, air entering a carburetor speeds up, creating low pressure, aka a vacuum that sucks in fuel from ports in the carburetor wall.

How It Works

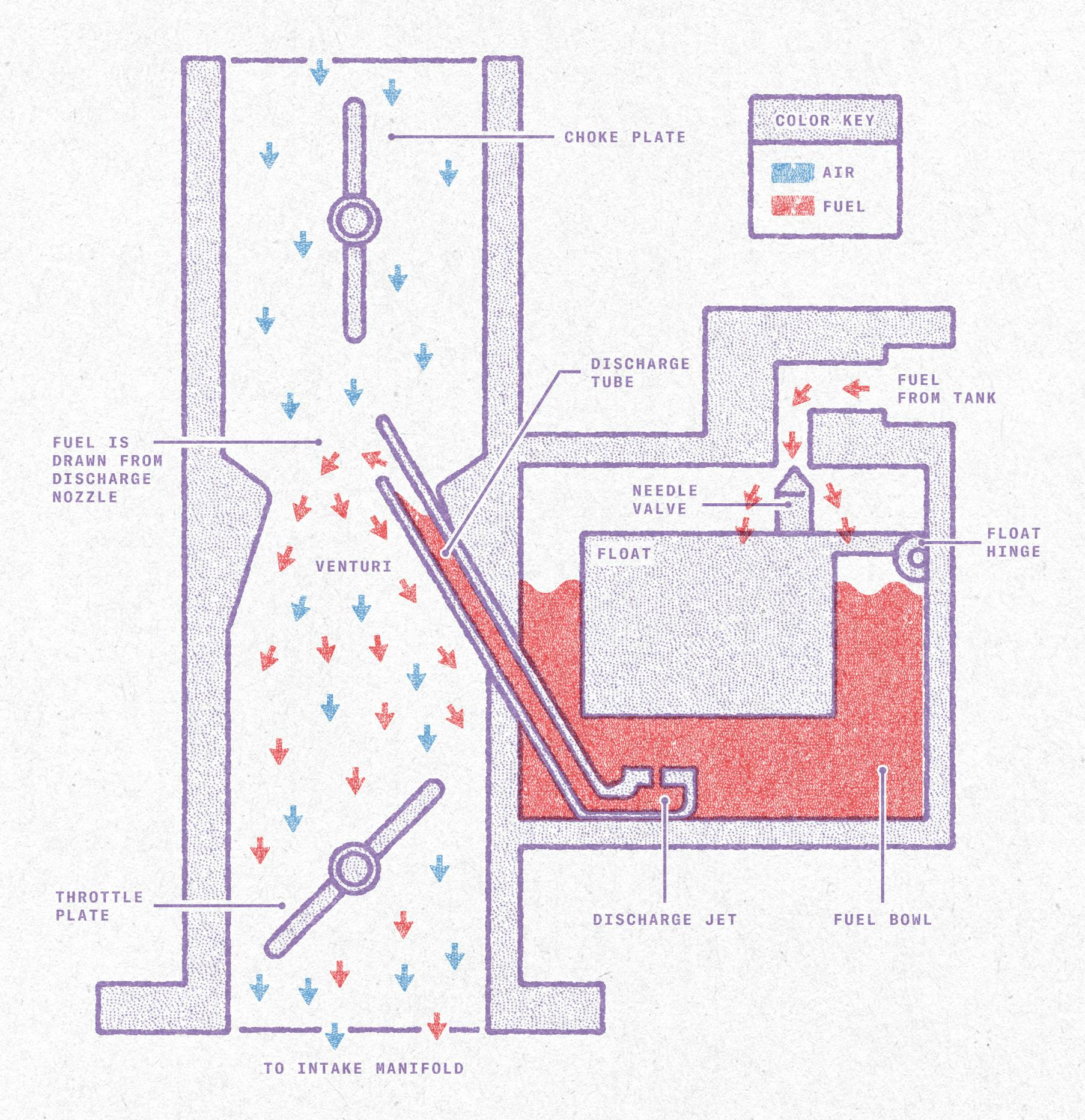

Air entering a carburetor’s venturi—a necked-down passage inside the carburetor barrel—rises in velocity. The resulting low pressure draws fuel from a nearby storage tank called the bowl (the fuel level in the bowl is critical to proper running and is determined by a float-and-valve setup).

In order for fuel and air to mix properly, the fuel must be converted from liquid to vapor. Atomizer nozzles, or jets, diminish the liquid to small droplets. Engine heat then evaporates these micro-droplets into vapor. A throttle blade—usually a round plate attached to a shaft—is controlled by the driver’s accelerator pedal and pivots inside the carburetor’s base to determine the amount of fuel-air mix admitted to the intake manifold for combustion. In some carbs, especially those on American cars, the carburetor is capped by a movable plate called the choke, sometimes controlled manually by a dash knob, sometimes by an automatic mechanism. In some conditions, usually when the engine is cold, the choke is mostly closed to enrich the mixture while further speeding up the airflow in the carb so that the vapor doesn’t have time to condense back into a liquid. Which is why a choked engine idles faster.

More Carburetor Parts and Terms

Carburetors employ from one to four “barrels” (another term for venturi), while high-performance engines typically use a dedicated barrel for each cylinder. Every carburetor has multiple “circuits,” or passageways, that admit fuel to the incoming air. The circuits correspond to various load conditions—the idle circuit, for instance, administers fuel to the engine when the throttle plate is closed. Another is for the accelerator pump, which makes the carburetor more responsive by injecting a shot of fuel into the carburetor airflow when the driver nails the accelerator pedal. Otherwise the engine would stumble until the air-fuel mixture can catch up naturally. A linkage system connects the throttle plate to the accelerator pedal.

Why They Went Away

Diesel engines, which first became available in cars in the early 1930s, don’t use carburetors; rather, they initiate combustion by squirting fuel under high pressure directly into each cylinder at precisely the right instant. Two decades later, engineers began adapting diesel-injection technology to gasoline engines in their quest for additional power, cleaner combustion, and smoother running. Bendix’s electronically controlled Electrojector fuel-injection computer became available on several U.S. cars in the 1958 model year.

Because their advantages didn’t fully justify their cost over carburetors, these early injection systems soon disappeared. However, once emissions controls were imposed in 1968, the need for more precise and carefully tailored fuel metering became imperative. By the mid-1980s, advances in fuel injection had relegated carburetors to history’s dustbin. Yet carburetors are still readily available for homegrown street tuning and racing applications.

***

This story first appeared in the January/February 2025 issue of Hagerty Drivers Club magazine. Join the club to receive our award-winning magazine and enjoy insider access to automotive events, discounts, roadside assistance, and more.

Just one more thing. When you remove the carb from the motor DON’T TURN IT UPSIDE DOWN! The check ball(s) and weight(s) can stick open in all the varnish.

I’ve successfully worked on many brands of carburetorsincluding downgrafts and side drafts, and multi- carb configurations. Out of all of them, a tip to set up a Holley 4150 double pumper properly is that not only do you need the standard carb tools but you also need a voodo doll which you shake over the top of the carb before making each adjustment. 😁

I’ve successfully worked on many brands of carburetors including down drafts and side drafts, and multi- carb configurations. Out of all of them, a tip to set up a Holley 4150 double pumper properly is that not only do you need the standard carb tools but you also need a voodo doll which you shake over the top of the carb before making each adjustment. 😁

If it’s worth telling a joke once, it’s worth telling it again…😛

Carbs have always been a bit of magic/voodoo to most people. I am happy to have electronic fuel injection myself.

Carb mixture screws bring out the fidgeter in people. When I work in a tool rental shop the first step when a chain saw or similar wasn’t running right was to set the carb adjustments to baseline and clean the air filter. This was usually enough to fix it after the user set the mixture wrong.

I wouldn’t say they have gone away. Look at Edelbrock’s latest version. At first glance, it’s another Holley clone. However, it’s so advanced that it gives any injection system a run for its money. It can meter within 1% of perfect in nearly all situations and will produce more power than fuel injection thanks to the charge cooling inherent to carbs.

I don’t think carbs will ever go away on small engines. The overhead of fuel injection just doesn’t make sense.

I have an original SBF tri-power on my Mustang. After sitting idle for 25 years, started up the engine and to no ones surprise the carbs all leaked. Sent them off to a rebuilder, got them back and followed their instructions on setup. It ran terrible. Spent months diagnosing everything else because the carbs were like new… Right?

Pulled the line on the front carb to check pressure and the engine ran great. Sent it back and they said there was no problem. Put it back on, same problem. Rebuilt myself and worked great. Eventually had to rebuild all 3 of them. Once they were all rebuilt, setup was not tough at all. Just sad you can’t always trust the pros you depend on.

I rebuilt two carbs in my younger days, a Lawn-Boy’s and a 1972 Super Beetle’s. That last one took all day, and was as complicated as I would ever want to get. I admire those who can rebuild and dial-in a Q-Jet.

I’m just going to add my $.02. While Holley carbs may seem complicated, in reality they are pretty easy to work on and dial in. At least I find it easy. That said, I have found, thru experience, that the ONLY rebuild kits that work well are genuine Holley kits. Expensive? Yes. Worth it to have a carb that works like new again? YES!

“Because their advantages didn’t fully justify their cost over carburetors, these early injection systems soon disappeared. ” That’s not the main reason, though I’m sure it’s one. The Bendix system just wasn’t fast and durable enough electronically. The electronics tech just wasn’t quite there yet. I’m an AMC/Rambler guy, and very familiar with the Bendix Electrojector history. AMC had 3-4 cars outfitted with it and at least two were at the 1957 Daytona new car show. They ended up not selling it due to reliability issues. The main thing is it wouldn’t work right if it were much below about 40 degrees outside or if it was much over about 100. Chrysler sold 35 or so cars equipped with it but all but a few were retrofitted with 4V carbs due to owner complaints (I know of only one still in existence — a 58 Desoto Adventurer — https://www.allpar.com/threads/1958-chrysler-desoto-electrojector-world%E2%80%99s-first-electronic-fuel-injection.228433/?post_id=1085222531&nested_view=1&sortby=oldest#post-1085222531).

Bendix sold the patents to Bosch. Bosch solved the cold problem by adding an additional injector in the intake to enrichen the fuel mixture under a specific temperature — just like a choke on a carb. Late 60s electronics handled underhood heat better, solving the high temp end. Bosch introduced it’s D-Jetronic in 1967.

A friend had an early to mid 70s Mercedes 280SE with the 3.5L V8 from the factory. I remember helping him replace all the little rubber hoses connecting the injectors to the fuel rail and thinking it looked remarkably like the Electrojector illustrations I have in some AMC literature on it. I’d love to install it on an AMC 327 and recreate a faux Electrojector car! Best would be a 57 four door hardtop (faux Rebel, or the real thing!), but even a later model would make an interesting phantom prototype/factory demo model… I’d definitely state it was a later addition and not try to pass it as an original Electrojector if installed in a 57 model.

In the late 70’s I got my Mom’s hand-me-down 1969 Chrysler T&C station wagon with a 383ci HiPo engine with dual exhaust and a Holley 4V. The float was soaked so with no knowledge (or knowing any better) I bought a rebuild kit and tore it down on my Dad’s workbench. After methodically taking it apart, spreading it out, cleaning thoroughly and putting it back together, it miraculously worked by just seating all of the adjustments and backing them out the prescribed amount. I didn’t have the knowledge or patience to really dial it in, but back then there were enough good mechanics around who could still do it. I drove it for a few more years until rust and leaks got the better of it (not to mention about 9 miles to the gallon). I would give anything to have it back!