Media | Articles

Mix Master: After 120 Years, the Carburetor Still Befuddles

To work on carburetors requires, first and foremost, a sense of humility. More than a century after their invention and some 30 years since their disappearance from new production vehicles, these intricate analog computers continue to bedevil even the mechanically inclined.

Yet all carburetors, from the one on a two-stroke weed whacker to the six Webers on a Ferrari 250 GTO, have the same core components and operate via the same principles. Understanding these fundamentals can help you tune your own carburetors or, at the very least, help you appreciate them.

An internal combustion engine, no matter how rudimentary or sophisticated, can only run properly if the liquid fuel in the tank is converted to gaseous vapor before it goes into the cylinder, and if the air and vapor are mixed in the correct ratio. To complicate matters, this ratio varies widely with operating conditions. During startup, the appropriate ratio is 8 pounds of air per pound of fuel. For peak cruising efficiency, twice the amount of air—16 pounds—must be metered for each pound of fuel. During acceleration, the ratio will momentarily drop to 9:1. Getting the ratios wrong by even a little—too much fuel and the engine is said to be running “rich,” too little and it’s running “lean”—causes problems.

Early History

Patents issued throughout the 19th century attest to repeated attempts to address these challenges. They generally proscribed a vessel containing fuel that intake air would skim across. The first device we’d recognize as a carburetor debuted, not coincidentally, on the first small high-speed internal combustion engine to run on gasoline, which was patented by Wilhelm Maybach and Gottlieb Daimler in 1885.

In 1899, brothers George and Earl Holley founded a carburetor-manufacturing enterprise in Bradford, Pennsylvania, later moving to Detroit to supply Henry Ford and other carmakers. By 1913, half of the autos produced in the United States were equipped with Holley carburetors.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The Physics

The “magic” at work in any carburetor is Bernoulli’s principle, which states that air pressure varies with the speed of its flow. Swiss physicist Daniel Bernoulli came to the idea by watching water flow in a river. At wide spots, the water slowed down, while at choke points, it sped up, meaning that speed and pressure were related. He published this theory in 1738. Aircraft employ the principle to produce differential pressures on their airfoils—higher below, lower above each wing—yielding lift. As with a river pinch point, air entering a carburetor speeds up, creating low pressure, aka a vacuum that sucks in fuel from ports in the carburetor wall.

How It Works

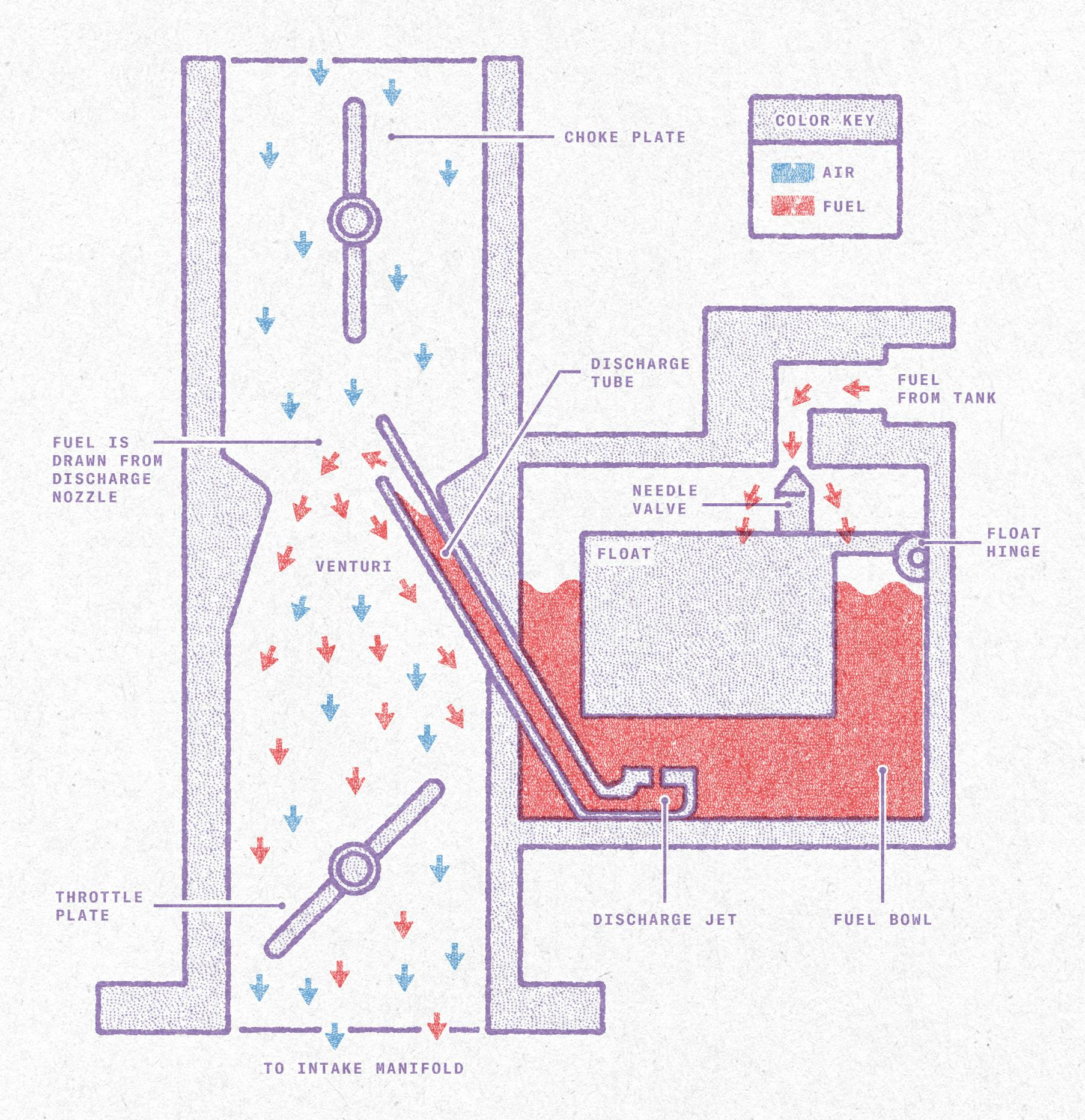

Air entering a carburetor’s venturi—a necked-down passage inside the carburetor barrel—rises in velocity. The resulting low pressure draws fuel from a nearby storage tank called the bowl (the fuel level in the bowl is critical to proper running and is determined by a float-and-valve setup).

In order for fuel and air to mix properly, the fuel must be converted from liquid to vapor. Atomizer nozzles, or jets, diminish the liquid to small droplets. Engine heat then evaporates these micro-droplets into vapor. A throttle blade—usually a round plate attached to a shaft—is controlled by the driver’s accelerator pedal and pivots inside the carburetor’s base to determine the amount of fuel-air mix admitted to the intake manifold for combustion. In some carbs, especially those on American cars, the carburetor is capped by a movable plate called the choke, sometimes controlled manually by a dash knob, sometimes by an automatic mechanism. In some conditions, usually when the engine is cold, the choke is mostly closed to enrich the mixture while further speeding up the airflow in the carb so that the vapor doesn’t have time to condense back into a liquid. Which is why a choked engine idles faster.

More Carburetor Parts and Terms

Carburetors employ from one to four “barrels” (another term for venturi), while high-performance engines typically use a dedicated barrel for each cylinder. Every carburetor has multiple “circuits,” or passageways, that admit fuel to the incoming air. The circuits correspond to various load conditions—the idle circuit, for instance, administers fuel to the engine when the throttle plate is closed. Another is for the accelerator pump, which makes the carburetor more responsive by injecting a shot of fuel into the carburetor airflow when the driver nails the accelerator pedal. Otherwise the engine would stumble until the air-fuel mixture can catch up naturally. A linkage system connects the throttle plate to the accelerator pedal.

Why They Went Away

Diesel engines, which first became available in cars in the early 1930s, don’t use carburetors; rather, they initiate combustion by squirting fuel under high pressure directly into each cylinder at precisely the right instant. Two decades later, engineers began adapting diesel-injection technology to gasoline engines in their quest for additional power, cleaner combustion, and smoother running. Bendix’s electronically controlled Electrojector fuel-injection computer became available on several U.S. cars in the 1958 model year.

Because their advantages didn’t fully justify their cost over carburetors, these early injection systems soon disappeared. However, once emissions controls were imposed in 1968, the need for more precise and carefully tailored fuel metering became imperative. By the mid-1980s, advances in fuel injection had relegated carburetors to history’s dustbin. Yet carburetors are still readily available for homegrown street tuning and racing applications.

***

This story first appeared in the January/February 2025 issue of Hagerty Drivers Club magazine. Join the club to receive our award-winning magazine and enjoy insider access to automotive events, discounts, roadside assistance, and more.

I have always admired anyone with more than one carb on their vehicle of choice. I had my hands full with a series of Quadra-jets built right here in Rochester. I also admired the folks who built them. Man!, there were a lot of small parts that could only have been assembled by hand. Kudos!

👍 I think a lot of folks don’t understand the refined mechanical design, as well as craftsmanship and assembly skills involved, not just in manufacturing, but also in tuning. It’s analogous to are those of us who will always make sure to double-check subtle things often overlooked or dismissed, such as spark plug gaps, tire pressures, and lug nut torque.

Once upon a time, when I rebuilt my first Q-jet on my ’81 K10, to get the idle mixture screws meticulously adjusted juuuust right, was an epic expression of patience, while roasting over a V-8 at operating temperature.

Maybe it was because the tips of the mixture screws weren’t perfect, but to attain that subtle, precise balance between correct idle rpms, and making the slightest adjustments to finally result in a dead-smooth idle, was very rewarding when it passed the emissions test, indicating I apparently nailed that elusive ideal 14.7/1 air/fuel ratio.

It is really gratifying when you get a carbuerator dialed in perfectly.

I remember my first attempt at rebuilding a Rochester Quadrajet. I bought a rebuild kit for the carb I got at a junk yard, got home, set up an area on a work bench in my shed, then proceeded to remove the top 1/3 of the carb. Once that was off, I marveled at all of the small parts I saw. Not knowing what they were all for, I decided to remove the bottom 1/3 of the carb, so I turned the carb over to start on that part of the task and watched helplessly as all of those small parts fell out. I stared at them with my mouth agape, for a long, “Oh, crap!” moment, wondering how I was going to get that all of that back together correctly (the carb rebuild kit had no instructions, meaning they expected the buyer to actually know what they were doing). Thankfully, I had a friend that knew his way around carburetors very well. After telling him what I did, he told me to gather up everything and come over. It gave me a sigh of relief and him a good laugh.

I’d love to see 8, 12 or 16 SU’s made with modern methods and materials on an engine. I never had a new one but by the time I got them, they were worn into individuals, like children. One of the bravest/dumbest things I’ve done is run a Holly on a rotary. Who would design a carb with a vertical gasket that spewed fuel every time you needed to change anything. Webers forever!!

I love Holley carbs. But I can’t argue with the fact that it’s a mess when you want out change main jets. I just put some old rags on the intake manifold to soak up the gad that spills, then go looking for some greasy parts to wipe clean. LOL.

Your name is very familiar. Did you autocross in the Buffalo area in the 1960’s- 1970’s?

He sang for Journey.

Did you vacation at my shop house?

Any story on carburetors always makes me think of the quote from author Dick O’Kane…”Carburetor is a French word for ‘leave it alone’. “

Cute, but you dont have to leave it alone. They are marvels of mechanical engineering, like a fine watch. At first they do appear daunting and complicated. Once you break them down into the various components, as described in the article, they are pretty straight forward, and can be mastered by an amature mechanic. The exception is the later carbs that interfaced with an on board computer (ECU). Those require a propane enrichening system to dial them in for emissions. I started out on single barrel motorcycle side draft carbs, and moved on to Holley, Carter, Rochester, Quadrajets (which I admit I never got a good feel for), and I have never been a professional mechanic. I was just a young guy with more time than money so I had to learn. My only carbuerator now is a Holley 770 Ultra Street Avenger, with an electric choke. The various systems like the idle circuit, accelerator pump, choke, Float bowl/main jets/mixing boards/ and vacuum secondaries, are all straight forward and not hard to rebuild and adjust if you just take one system at a time. I think there are dozens of on line vieos from Holley, and others on You Tube that walk you through just about everthing, if you ever decide to take the plunge.

The greatest issue is people do not learn or educate themselves on how to tune or adjust carbs,

We sell tons of them and get calls saying it is bleeding over, or they will say it is too rich.

I would as did you adjust the carb they say yes. I would ask what did you do. I turned the mature screws.

I then ask did you rejet the car or even set the float level. Most say no and that they should not have don this on a new carb. I then have to explain this is not a model specific carb and it needs tuned to their set up. Also opening the carb up will not void the warranty.

The lack of knowledge is over whelming.

I know very good engine builders that will still not adjust a carb correctly or in some cases buy the correct size. So many people buy a 7t0 double pump and wonder why they fowl plugs.

Also everyone is making 600 hp. No Dyno and I yo one compression but their buddy said it would make 600 hp.

A little education and practice carbs are not as intimidating as they appear. Edelbrock are great first the street and for learning how to tune since the rods are easy to change.

I bought my fuel injected ’57 Corvette at a time when the FI units were universally being ditched for carburetors because many folks couldn’t get them to run. Knowing how carburetors worked allowed me to read up on Rochester FI and get it to run perfectly. They work differently but they have to perform the same tasks so I was able to diagnose and adjust my FI. Taking the time to educate oneself goes a long way.

If you aren’t into Bernoulli or algebra, the key thing is learn how to take them apart, clean them, and put them back together

Once you get the take apart/put together part down, now it’s time to tune

Start simple – square bore or two barrel… Our friend the Quadrajet and it’s spreadbore relatives are trickier beasts

The first thing is figuring out where you are at. Disconnect the accelerator pump and snap the throttle. Did it get better or worse? Better – too rich. Worse? well we kinda expect that, so put the accelerator pump back on and hold the choke a little closed. If it got better that time, lean. Now figure out what jets you have and start going up or down a few steps at a time until you get some pretty crisp accelleration. I tend to err on the side of rich. Rich costs a little more money down the road. Lean kills engines.

I’m a “younger guy” (30’s) so I grew up in the TBI/FI-era, in a family who would be lucky to figure out how to bleed brakes. My first exposure to carbs was on my ’87 wrangler; after day 1 of owning it, the Carter had internal vacuum leaks, so a Weber swap it was. Adjusted it once in the 2010’s and it’s run fine since, so I learned nothing.

Next I bought a boat that didn’t run right; the owner tried to rebuild the Q-jet and installed the secondary metering needles backwards. A partial disassembly and reinstallation correctly fixed the flooding issue, learning the concept of how a 4-barrel carb in the process.

A few years ago I bought a restored Comet that had been sitting for half a decade in a shed, so the Holley needed a rebuild. I learned the joy of scraping felt gaskets. Still extremely complicated and I didn’t get it right, so I shelved it and threw on a spare I’d acquired.

Lastly, I attemped an Edelbrock rebuild on a 70’s camaro 305, by far simpler than the Holley. Tearing down, documenting, and rebuilding these allowed me to better understand how they worked. I’m still not great at tuning them, but knowing which screw does what has helped me do a decent job without any sort of guidance or instruction, aside from knowing which component does what during startup, idle, and acceleration.

I am a 71 yo wrench bender. LOL. I was extremely dismayed by the shop results I was getting on my quadrojet so I decided I would have to learn how to rebuild one myself. For about 7 or 8 months I searched for every possible printed paper work on a quadrojet. I took notes, I read and reread everything I could find. Then I developed my own style for an effective rebuild. My name got around. I lived in the Dallas area. One Saturday morning at about 10 am a young man was knocking on my front door. He was from Los Angeles and had heard about me. He was on his way to New York city to work on a big job that was going to be starting soon and could I please help him with his El Camino? I had him pop his hood so I could do a preliminary inspection. I soon found that the problem was a pinched vacuum line. I rerouted the vacuum hose and we went for a test drive. The car performed flawlessly. He was tickled to death. I think I charged him 20 bucks. There were many other instances where I was a hero for someone that had almost lost all hope. When I first started doing my research there was an old man in a coffee shop that told me I was wasting my time because th quadrajets were just too complicated to work on. Later, after I was accepted as being knowledgeable then he wanted me to rebuild one for him.I reminded him that the quadrajet was too complicated for me to work on for him. Lol. He stayed mad at me for the rest of his life.

The Edelbrock has some nice tuning features. Don’t give up on the holley though. Gasket scraping is a pain. the trick is when you install the new blue gaskets rub a little chapstick on them and they relaese much easier if you have to disassemble ever again. Ther are tons of great videos on line that walk you through rebuilding Holleys and trouble shhoting them too.

Well it all starts with do you have the right size Carb. The most critical issue is people buy the wrong size.

Most V8 cars need 500-650 CFM single pumps and that is all for the street.

Then you need to set float levels and make sure the pressure is not too high from the pump. If it is you need a regulator.

Set the idle and then smell and read the plugs. If you are rich you may be able to turn down the mixture screw a bit. If not you will need to rejet or change the metering rods depending on the carb.

Once you get that in you can play with the accelerator pump and other bits for drivability if needed. This is a simple out line but generally what needs to be done.

Note if you install a carb and it is bleeding over from the start. You may need to take a wood handle from a screw driver or hammer and rap the side of the carb. Floats get hung up in shipping and often can bleed over. Do not return the carb as it can easily be fixed and save you a lot of time swapping.

The real key is reading the plugs. This will show how rich or lean you may be. It may take some guess work at first and then you will dial it in. Experience here often saves time but it takes time to get experience.

There are other tricks to learn. I ran a tunnel ram on the street with two 4 barrels. It was my first attempt and dual quads. I had issues with the idle circuit. It flowed way too much and Holley did not make restrictors anymore. An old timer showed me to use a piece of wire half the side of the idle circuit and pit it in the carb on a bend in the circuit. That cut the flow in half. It ran great after that.

Other set ups like Tri Powers are not all that hard as the end carbs are more for full flow. Mechanical linkage is not hard but vacuum linkage can be a bit of a challenge if it is not right.

I’m no where near an expert here on carbs. I know the ones I work with the most. But you learn and if you can have someone teach you all the better.

I got pretty good at Holleys having had a few. Pump cams, nozzles etc. My last bike was a Suzuki GS850 with 4 Mikuni’s. It left me stranded once, dead lean. Checked everything and decided to pull the carbs and clean them. Tanked them twice then sprayed with carb cleaner and air. Got it to run but it was still flat on accel. Turn the choke on and it would wake up a little. Plugs still white. I gave up and sold it. Don’t know what I was missing to fix it.

I had carb problems on my Suzuki also. Primarily from letting it sit for months without running it. I dumped a can of Seafoam into the tank and let that run through the carbs. It eventually cleared what ever was clogging the carbs up.

Carburetors are the most reliable and dependable as long as you have a well designed and built unit. Specifically for gasoline fuel and the typical engine it’s operating. The main reason for the mentioned facts is that it does not require an unbelievably stupid (Designed To Fail) government idiots computer to control them. That’s why they were in use all them years because they are simple and reliable. The obvious fact is when auto repair insurance became reality, not to change subject but the latest idiot requirement- ( Diesel Exhaust Fluid) W T F come on people how much more B S are we going to put up with?

Reliable and dependable, yes, but anyone with half a brain knows fuel injection is not actually that complicated and can produce similar power with an increase in efficiency. Those computers were not put there by the government, nor are they “designed to fail.” If they were, why are so many 1980s and ’90s vehicles still driving along just fine. Your conspiracy theory falls apart with literally any critical thought applied.

Nothing wrong with being a luddite, but don’t act like technology has not progressed significantly and those advancements help the vast majority of normal people.

Fuel injection isn’t really any more complicated, it is just a lot of additional infrastructure. At a minimum, a high pressure fuel pump, a computer, an O2 sensor, a MAP sensor, and an engine temp sensor… just to get going. If you really want the improved efficiency, you need a MAF sensor, three more O2 sensors, spark control, etc.

I take my opening statement back.

They are reliable, they aren’t designed to fail, but you are replacing a $300 component with 2 to 3 grand in stuff to get maybe a 5% increase over a properly tuned carb. I suspect most of the stuff around EFI (like tuned intakes and free flow exhausts) have more to do with the performance and efficiency increases of the modern era than the fuel injection does

Fuel injection can provide more precise metering, which can result in cleaner Hp and better fuel economy. Cold start and drivability are very good.

With the correct carb size, intake, cylinder head, camshaft, and exhaust a carb can provide significant advantages. The least of which is increased air column density due to evaporation of fuel at the Venturi.

This is why GM TBI engines make significantly less HP than with a cast iron Quadrajet intake and carb, AND why the vortec CPI system makes more. You can’t just slap a TBI on a carb intake or a carb on an EFI engine.

Where this goes wrong is Mis-matched parts that destroy the carb signal and even worse folks that “know how to tune a carb and set timing.”

I’ve had many a mechanic yell, scream, and curse at me when I told them their tube was wrong and demonstrated the proper way.

Well said.

I agree that all this technology is a bit of a pain but I still remember what the air was like 50 years ago. Red eyes and a sore throat because of the filthy air and since then the number of cars has more than doubled. I love being able to breathe. The government and private industry fixed it. Government isn’t always bad.

How much dirty air are you willing to put up with? Most of us like to breath clean air – and EFI (along with other newer technology) is much better at maintaining that clean air. I would not go back to the carb, even if I could.

I love working on my “old”Holley carbs. From a 500 cfm “two barrel” to a 850 cfm “double pumper”. It’s the heart of the engine. Tuning, air,fuel and timing in that great mechanical symphony. Nothing like it. 🏁

I’m also a Holley fan. The 4150 & 4160 series (and their clones) are fine pieces of engineering. They can be made to be both efficient fuel-wise and power-wise once you become acquainted with their circuitry and operation. Two of my vehicles (Chevy SBC-powered) have Holleys, a ’48 Olds with an 1850-1 and a ’67 Chevy II with a 3310-1.

I also have HP Tuners for the two modified vehicles (CTS-V & C1500) that I have that are fuel injected. The calibration is done with a keyboard instead of screwdrivers, but it’s still as challenging/interesting.

Both systems can only be as economical as your right foot will allow.

Actually Some Carburetors are dependable. There are some that are a pure night mare.

Lean Burn anyone? You fix it by removing it and going with an older system. Same on many computer controlled carburetors.

The fact is Fuel injections is just a better system. It can put an exact amount of fuel in the cylinder for not only better cleaner burn but more power.

In the case of Direct Injection we can push up Compression and or boost to levels we never could as it cools the piston and prevents knock.

I was able to run 23 pounds of boost on pure pump gas and made 300 HP from 2.0 liters. No Carburetor would ever do that.

Like Carbs there are some poor systems with FI but many are much more beneficial.

The FItech aftermarket systems are priced well and work great. They are selling as well or better than Carbs in many cases today.

Like anything else there is good and bad but their is also a learning curve with many new things and there are great benefits today to this.

Gasoline direct injection is next level for high. Ranking compression and/or boost. It literally allows safely running on the edge.

I run 20 psi normally, not so much the boost but the volume, as boost is a measure of restriction. My head flow is more than Boss 429 CJ, but on a 387 LSx.

I love me some carbs and have a zen thing with the Quadrajet, but there isn’t a carb wizard out there that will make the kind of power I’m making, streetable. I can idle this ridiculous caricature of excess in car loop for 25 minutes, drop off my little girl, then once out of the school zone, hit 7k cleanly and quickly.

As many have stated before me, carbs are indeed befuddling and scary – until one pushes past the fear and mystery and just learns how they work and what it takes to properly select and then tune them. I remember back in the days when there were only a few guys in town who you’d take your carbs to for a rebuild and/or set-up. Then rebuild kits became commonplace and many of us thought we could figure it out ourselves. Most of us figured out that those few guys had been smoke screening us all along. Not to make it sound overly simple, but like most things on analogue cars, carburetors CAN be mastered.

These days, I enjoy opening up a carb on the bench for nostalgia’s sake more than anything. But I absolutely enjoy starting up my daily drivers with their EFI ease and efficiency. Some (not all) progress is indeed progress!

I once had a carb on a ’60s two-stroke twin motorcycle- not leak, but suddenly spray- gas out everywhere. I pulled into a handy gas station. My buddy that was riding with me said it was spraying all over the side of the engine and rear tire, and we should call a tow truck. I unscrewed the top (a Hitachi) and the float had cracked the solder that held the bulb to its hinge (yes, 2-strokes vibrate a tad). I borrowed a soldering iron from the station, resoldered the float assembly in a few minutes and we continued our ride, needing no tools except the soldering iron. Didn’t even need extra solder. My buddy was in awe. Carbs are not complicated but you gotta understand them!

Sounds like in this case you went beyond “understanding” over to “teaching it who’s boss.”

Aside from ethanol fuels, carbs are very reliable once you get it dialed in correctly for your engine. My Holley 2 barrel on my flathead is as reliable as the sunrise.

I think ethanol gets blamed for a lot of mystery problems it’s not really responsible for. I’ve learned that ethanol is very good at cleaning out your fuel system and depositing the gunk in the carburetor, but once you start running it on a regular basis, everything is fine.

The big problem with ethanol is that it pulls water out of humid air. It’s not an issue for daily drivers, but it’s a real problem with things like lawnmowers that sit all winter. Or cars that sit all winter.

True that. I built my latest vintage engine to run on pump gas (in about 2007) but the info on ethanol fuels was a bit spotty at the time and I was using it for a bit before I started noticing some water in places where water should not have been. I asked around and got some more info, which led me to draining a gas tank that’d sat over two winters full of fuel that was 10% ethanol. There was indeed water in the tank. That’s the last ethanol gas that has ever been in that car!

Storage fuel and unleaded race gas solves this issue. They can sit without boiling off the light HCs, they don’t absorb water, eat rubber parts, or suffer octane decay.

Well yes, I learned to treat my gas for storage, but at the time, that wasn’t widely-spread knowledge. As for race gas, maybe you missed that I purposedly built the engine to run on pump gas. Race gas wasn’t always available on road trips – still isn’t!

Great article- But Holley was founded in 1896, not 1899 as the article states

The two components/systems least desired to work on by fellow mechanics who worked around me during the 80s & 90s were carburetors and automatic transmissions. Being fortunate to have a few good instructors that broke down each one in simplest form, it took the fear out of working on them.

One instructor told the class about the acronym F.L.I.P.C.A.M. Each letter represented one of the carburetor’s seven basic components. For example, ‘F’ for float, ‘C’ for choke, ‘M’ for main jet (sorry, but after 40+ years, I’ve forgotten a few!). He might have been one of the first that I heard say “K.I.S.S. – Keep It Simple, Stupid!”. Yup, I needed ‘Simple’!

Another instructor told his class that automatics were easy when also keeping it simple: hydraulic pressure, power flow through the transmission and its parts, and parts replacement. The last item may not sound correct, but he, the instructor, explained that, with almost no exception, there were no parts that could be repaired. And most testing/diagnosis was visual. If the part was worn, replace it. If the part was broken, replace it. If the part was some type of seal, replace it. If the part was good, clean it and use it. EZ PZ!

Many people just never learned carb tuning or repair. It is alway secondary to engine rebuilding.

Too often people who do work on them get in over their heads and create more issues.

Today with so few carbs it is becoming a lost art working on one.

As there are also many good carbs we have had a share or crap carburetors too. In these they can be near impossible to tune and adjust. The lean burn for example is best tuned by removing it and going to an older mopar setup.

Buying a carb to learn on is key. The Edelbrock units are the easiest to tune and great street carbs. Most everything can be adjusted on car and no need to remove float bowls for tuning.

Ah yes the carburetor. As I have often said it’s a French word that means fix me last.