Media | Articles

Lamborghini’s first V-12 lived large for 48 years

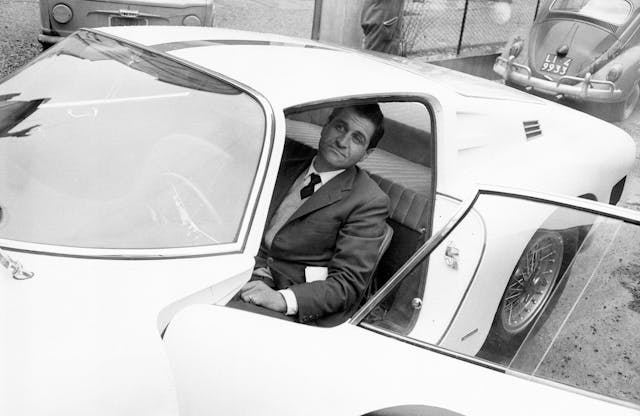

There are a few versions of the well-known yarn about how Ferruccio Lamborghini got in the car business. Some say he was personally insulted by Enzo Ferrari. Some say il Commendatore never granted him an appointment. In a 1981 interview, Lamborghini said that he had owned three Ferraris by the early 1960s. They were always wearing out their clutches, and when he took them back to the factory, Enzo told him: “‘You don’t have the slightest idea how to drive a Ferrari. You’d rather drive your tractors.’” Spurned, Lamborghini supposedly tore back up the road to his tractor and home-heater factories in nearby Cento, determined—as only a hotheaded Taurus can be—to crush Ferrari.

Those who knew him say Ferruccio never worried too much about whether a good story was true or not. Even if this legendary encounter happened, financial logic and incremental thinking were what drove Lamborghini’s attempt to try to skim a profit off of Ferrari’s apparent disdain for his customers. Before he would lay out for a car, the tractor baron wanted to see if he could first produce a satisfactory car engine. What resulted ended up being the Chevy small-block of Italian V-12s, adapted to an astounding variety of vehicles both on land and on water for nearly half a century.

Ferruccio had always loved engines, had been tinkering with them since he was a farm boy in northern Italy. When it came time to create his own, though, the stout, square-shaped Emilian chose to hire others. Unlike Enzo, he was, in the words of Road & Track correspondent Griff Borgeson, writing in 1964, “one of those rare Italian executives who do not have an instinctive aversion to the delegation of personal authority.”

His first hire was Giotto Bizzarrini. The Tuscan son of a wealthy landowner, Bizzarrini had served as an engineer at Alfa Romeo during its postwar revival glory and had also worked at Ferrari on the 250 GTO. In late 1961, at 36, he was swept up in a mass walkout/firing of disgruntled engineers that rocked Maranello (if Enzo was indeed huffy with Lamborghini, perhaps this was the reason), and he was looking for work for his fledgling engineering consultancy, Societa Autostar.

The physics of a reciprocating-piston engine dictate that an inline-six offers the most inherent balance, as the primary vibrations generated by piston motion cancel each other out. The concept of joining two such engines at the crankshaft to make lots of sublimely smooth power has been attracting upscale automakers since Packard pioneered the V-12 in 1915. A four-stroke V-12 supplies a power pulse every 60 degrees of crank rotation, creating such a rapid cadence of pulses that when accompanied by other build choices, such as making the block vee angle 60 degrees, the vibrations are minimal.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Lamborghini had another reason to want a V-12: He loved to flaunt his wealth. Italy’s oppressive taxation of engine displacement meant anyone jockeying a V-12 was the undisputed king of the autostrada—and had definitely come a long way from the farm. Besides, Ferrari had made V-12s an Italian specialty since Enzo became enamored with the Packard in his youth. Ferrari’s illustrious Colombo- and Lampredi-designed 12s, including the 2953-cc unit from the 1962 GTO, were the reigning gold standards of Italian racing and road engines.

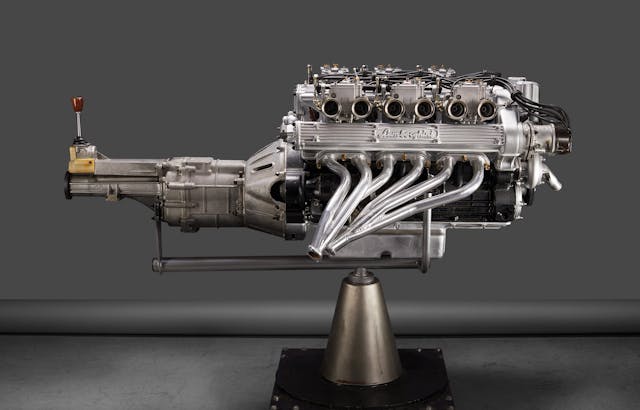

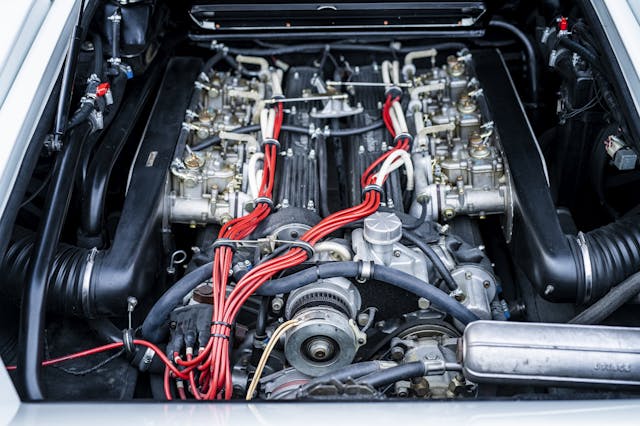

Lamborghini commissioned Bizzarrini to do the groundwork, his stipulations being simple: a V-12 with four cams, six carburetors, and an oversquare configuration, meaning a bigger bore relative to the stroke. The wider bore enabled larger valve openings for better breathing, while the shorter stroke permitted higher revs due to the reduced inertial forces of the pistons and rods in motion. The wail from such engines has long been identified as the mating call of an Italian exotic on the run.

Bizzarrini asked to be paid a fixed fee to match the Ferrari’s 300 horsepower, plus a generous bonus for every pony his engine produced over that. It might have seemed like a good deal to Ferruccio at the time, but it meant he didn’t get the exact luxury GT engine he wanted. Bizzarrini focused almost entirely on peak horsepower. In his back pocket was the design for a V-12 screamer sized at 1.5 liters to meet the then-standard for grand prix racing, but it took some finessing (and a lawsuit) to get there.

As with the Ferrari, Lamborghini’s engine used a 60-degree vee angle with a block and heads cast in aluminum, but the similarities largely ended there. Enzo’s engines mainly employed single-overhead camshafts, as did other great V-12s of history, including the Rolls-Royce Merlin. However, Lamborghini wanted double-overhead cams, a mandate that may have been pure vanity. “I think Lamborghini’s thought was, ‘I want it bigger and badder than a Ferrari,’” says Los Angeles-area Lamborghini specialist Robert Huber. “‘If they have three carbs, I want six. If they have two camshafts, I want four.’”

The double-overhead-cam design did allow for more freedom in the valve angles and plug placement, without requiring the extra complexity of rocker arms. It’s a freedom Bizzarrini exploited to construct a deep, semi-hemispherical combustion chamber that had plenty of room for the larger, opposed valves the engine required to breathe efficiently at high rpm. Going with four cams from the start also made the engine’s adaptation to four-valve heads much simpler when they finally arrived in the mid-1980s.

Bizzarrini needed to upsize his 1.5-liter design for the much-heavier GT car Lamborghini hoped to build eventually. The bore and stroke increased to 77 millimeters and 62 millimeters, respectively, making for an initial displacement of 3465 cc, or 212 cubic inches. At not quite 2.5 inches long, the Lambo’s stroke was a compromise between achieving durability and reasonable torque production and making possible engine speeds above 7000 rpm, which was the only way he could beat the Ferrari engine on horsepower. Each of the 289-cc cylinders were capped by relatively large induction and exhaust valve diameters of 42 millimeters (1.66 inches) and 38 millimeters (1.49 inches), respectively, the valves snapping down on soft bronze seats.

The forged-aluminum pistons sported domed crowns with inset cavities to give clearance for the valves. The domes pushed up the compression ratio, but at the expense of obstructed breathing and flame propagation—one reason you don’t commonly see domed pistons today. They ran in iron liners pressed into the block so as to stand proud off the closed deck by a few thousandths of an inch; this pinched the steel-ringed head gasket for optimum sealing.

The crankshaft started life as a 204-pound billet of SAE 9840 nickel-chrome-silicon alloy steel that was machined, polished, and balanced into a beautiful rotating sculpture of counterweights and journals. The V-12’s bottom end had to be strong to keep the long, heavy rotating assembly from bending in the middle at higher revs. Within the deep-skirted crankcase, seven forged-aluminum bearing caps were lined with British-made Vandervell bearing inserts and solidly fixed in place by four studs each.

The Ferrari engine used a single timing chain for both of its cams, driven by a sprocket on the end of the crankshaft. Bizzarrini developed a more complex arrangement for the Lamborghini. Instead of a chain sprocket, he placed a pinion gear on the end of the crank to drive two large helical gears, each sized to turn at half-crank speed on a pair of ball bearings and short axles pressed into the block just above the crankshaft. These gears had incorporated sprockets that each drove a separate timing chain for the cylinder heads.

Bizzarrini packaged this hybrid of a chain-driven and geared-cam arrangement, which obviously needed constant lubrication, all inside the block. That greatly reduced the amount of sealing surface—and potential leak points—at the front of the engine, versus Ferrari’s solution of a separate bolt-on timing-chain case. Dividing the cam-drive duties among two chains meant the accumulated stretch of the chains over time was less than that of a single long chain, so a mechanic wouldn’t need to go in and re-tension the system as often.

Variable valve timing and lift didn’t exist then, so engine designers were stuck choosing one timing and lift profile for the camshafts. High revs or a smooth idle—take your pick. In the Lamborghini, Bizzarrini chose high rpm, grinding the hollow, internally lubricated camshafts with a deep lift and a healthy overlap between the intake and exhaust that let the cylinders breathe at revs. It also produced a lumpier and fairly pungent exhaust at idle from all the unburned fuel escaping while both intake and exhaust valves were open. The cams pushed on flat lifters shaped like inverted cups—the original Italian shop manual refers to them as bicchierini, or “shot glasses”—under which were solid shims for setting the valve lash.

The choice of quad cams resulted in big and bulky cylinder heads, with barely enough space between the heads to slide a hand down. That meant there was no room to put the intake ports in the vee, where they are on comparable Ferrari engines. Instead, the intake ports were incorporated into the crowded valley between the cams, along with the spark plug holes and the head studs.

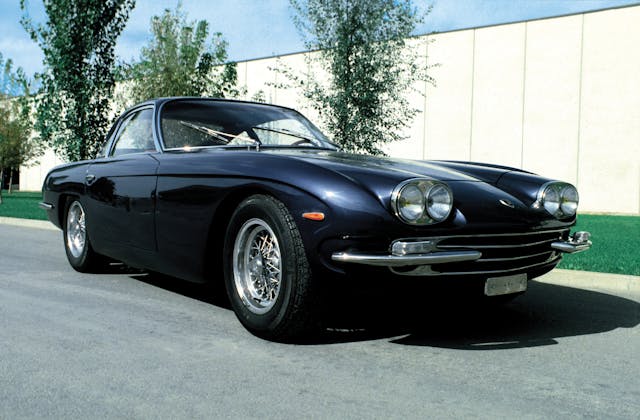

Although this meant a less-straight path for air flowing down into and across the cylinder, it also made possible the fitting of horizontal sidedraft carburetors (and their associated filter boxes) as well as vertical downdraft carburetors, which is partly what made the Lamborghini V-12 so versatile in the years to come. A six-pack of sidedraft dual-choke Weber 40DCOE carbs, operated in mechanical chorus by an elaborate cable-crank-pushrod system that requires a heavy right foot, is found under the hoods of Lamborghini’s earlier front-engine cars. The sidedraft carbs allowed the company to explore lower hoodlines and more modern, folded-paper shapes in the late 1960s, when Ferrari was still squeezing downdraft carbs under the bulging, big-headlight curves of an earlier era. Indeed, it wasn’t until 1971 that Ferrari responded with its own sidedraft, four-cam 4.4-liter V-12 for the low-slung 365 GTC/4 coupe.

Bizzarrini’s other departures from contemporary mass-production engines included placing the water pump and the oil pump entirely outside the block, the former turned by a cam-chain sprocket, the latter by a keyed notch at the tip of the crankshaft.

Mounted to the company’s new Schenk dynamometer in May 1963, fitted with downdraft carbs, and with a compression ratio in the range of 10.5:1, the first prototype made 360 horsepower once the test engineer eventually cranked it up to 8000 rpm. Bizzarrini put his hand out for his cash, but Lamborghini refused, saying he effectively had a racing engine that would only make 360 horses in an unrealistic test. The two lawyered up and words flew, but, according to the current head of Lamborghini’s historical department, Paolo Gabrielli, Ferruccio probably just paid off Bizzarrini. They parted ways permanently in 1963.

Lamborghini’s next hire was Gian Paolo Dallara, a tall and bespectacled sprig three years out from Politecnico di Milano, where he had been studying aeronautical engineering. Despite being 25, Dallara already had an impressive résumé, having gone first to Ferrari to help launch the company’s initial forays into wind-tunnel testing, then to the Maserati racing program. At Lamborghini, he went to work designing a car for the engine while Paolo Stanzani, another Maserati alum who was working in Ferruccio’s tractor business, got the job of taming Bizzarrini’s engine for road use.

Stanzani dialed back the cam profiles to reduce the horsepower to about 325 but also to raise the midrange torque and improve the idle. He relocated the twin horizontal distributors, each one delivering spark to six of the V-12’s cylinders, from the back of the engine where they would bump into the firewall of any future GT car, to the front where they would run off the exhaust cams. He ditched the dry sump, adding an expansive finned sump that held more than 12 quarts. That vast quantity was a measure to improve cooling as it let oil sit in the underbody airstream for longer to shed heat. Later versions of the engine held as much as 18.5 quarts at a time when most cars got by with 6 or fewer.

With the engine thus showing promise, Lamborghini commissioned the then-relatively unknown designer Franco Scaglione to draw a prototype car and another obscure shop, the Sargiotto Bodyworks of Turin, to quickly gin together a non-running showpiece in time for the 1963 Turin Motor Show. The resulting emerald-green 350 GTV had the face of a whale shark, batwing fenders, six peashooter exhaust pipes, and Lamborghini’s garish signature across both the nose—and, in case you missed that, the rump. It drew smirks, but the Cavaliere was undaunted. Enough forward-looking elements were present that when the more prestigious firm of Carrozzeria Touring got involved, the 350 GT that evolved from the prototype was a car that Ferruccio was willing to put into production.

Everything was done in a rush in those early days of Automobili Lamborghini. Not even two years had passed since Dallara signed on, and finished cars (granted, a mere 13 that first year of 1964) were rolling out of what had a year earlier been an empty farm field near the village of Sant’Agata. The cars as well as their new V-12 were in metamorphosis immediately. After a run of 120 copies of Lamborghini’s initial 350 GT model, the V-12 was bored out to 82 millimeters by substituting the 350’s iron liners for ones with thinner walls. This increased the displacement to 3929 cc.

Dallara upsized the head studs and corrected a problem with Bizzarrini’s original design, likely stemming from its origins as a racing mill. On initial start-up, the engine piped cold, semi-coagulated oil to the cylinder heads where it pooled, reluctant to dribble back to the sump through the six small 10-millimeter drain-back holes. That was fine for a racing engine that’s carefully run up by mechanics so that the oil rises in temperature and thins out before the engine is called on for duty. Demanding the same patience from a civilian blue blood was a recipe for disaster, so Dallara opened up the drain-back holes so that Lamborghinis forced onto the road while still cold wouldn’t starve for oil.

The front of the engine likewise became a game of musical chairs as the 350 GT gave way to the 400 GT, which then led to the increasing complexity of the Islero, Espada, and Jarama models. The two distributors became a single large one, the alternator moved around and then split into two alternators, and a hefty York air-conditioning compressor joined the crowd—as did, later, a power-steering pump.

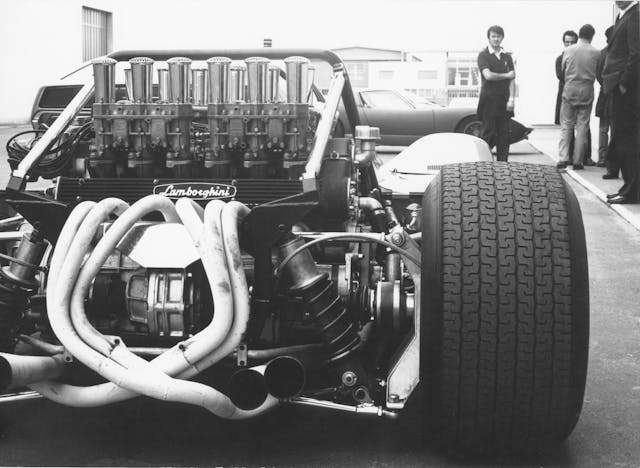

Racers at heart, Dallara and his cohorts, including New Zealand mechanic and test driver Bob Wallace, wanted to see their V-12 move behind the seats. A longitudinal layout such as that of a Ford GT40, in which the engine and transmission sit on the centerline of the vehicle, would make for a very long car and compress the cockpit space, unless the wheelbase was stretched to an ungainly length. Brainstorming in mid-1965, Dallara, Wallace, and Stanzani threw the company’s V-12 engine, a five-speed transmission, and a differential on a chassis table in the factory and literally moved the components around by hand, arguing and taking measurements.

They realized that their compact little V-12 was just 21 inches in width. Inspired by the transverse-engine, front-drive Austin Mini (as well as Honda’s RA271 grand prix car of 1964, which had its tiny 1.5-liter V-12 mounted sideways, motorcycle-style), the team decided to rotate the V-12 by 90 degrees and drop it in sideways behind the seats. The transmission and differential would sit within a modified engine-block casting, their internals lying parallel to the crankshaft along the engine’s aft side and with a shared oil sump. Besides neatly concentrating the powertrain’s mass in the center, turning the V-12 sideways (which meant running it backward, or counter-clockwise) allowed space within the short, 98-inch proposed wheelbase for a two-seat cockpit to sit fully behind the front axle for better foot room. And it would finally allow Dallara to use racing-style vertical downdraft carburetors, as their height would be tucked in behind the cabin of whatever body the designers drew to clothe the chassis.

Bertone’s newly promoted chief designer, a young Marcello Gandini, took up the project with gusto. The resulting finished car, named after champion fighting-bull breeder Don Eduardo Miura, appeared at the 1966 Geneva show. Buyers swarmed, and over the next five years, the company produced 764 Miuras, the horsepower rising to 380 in the final P400 SV due mainly to a 10.7:1 compression ratio and revised cam timing.

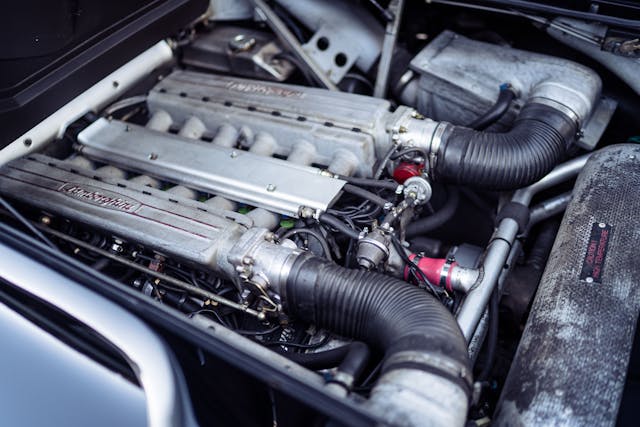

Ferruccio got in the car business to produce luxury front-engine GTs, but the stunning Miura came to define his company’s image. When it came time to replace it in 1972 with the even more outrageous Countach, Stanzani—who took over from Dallara when he left in 1969—once again rotated the V-12 another 90 degrees, now to face rearward. The transmission slotted beneath the seats under a broad tunnel that made the Countach singularly terrible for in-car canoodling, but it concentrated more weight on the car’s roll axis, which improved the handling. Additionally, it meant that the driver shifted gears directly, no cables or linkages required. From the end of the gearbox, a prop shaft ran aft through the engine’s sump to the differential, which was also in the sump.

Backward to go forward

- When it came time to replace the Miura with the even more outré Countach in 1974, Lamborghini rotated its engine 90 degrees once more and installed it backward. The V-12’s flexibility was again proven with the Quattrovalvole of 1985, which added 48-valve heads to the now-5.2-liter block to produce 420 horsepower in the federalized, fuel-injected model.

- Out-of-the-box thinking saw the rear differential incorporated into the engine’s sump, just below the water pump, distributor, A/C compressor, and other accessories normally found at the “front” of an engine.

- Dished pistons and four-cam heads were new in the Countach QV, but the block was much as Bizzarrini had designed it in ’63. An E ticket for drivers, it was a nightmare for mechanics.

Such inverted thinking proved the best way to power a lunatic vehicle that was more art than automobile, even if the long stack of transmission, engine, and differential needed to be stuffed through the Countach’s small porthole of an engine hatch at an almost vertical angle at the factory. The design forced a switch back to sidedraft Webers, albeit with larger throats sized at 45 millimeters, which cut the first Countach’s rated horsepower down to 375.

Ferruccio Lamborghini sold his last stake in the company in 1974, leaving further development of the V-12 to a series of pie-eyed investors who lined up to be bled dry by the needs of a boutique automaker facing the onslaught of increasing regulations. Tight finances meant continuous life extensions for the aging V-12, and it grew in the Countach—first to 4.8 liters, then to 5.2, the latter getting the four-valve cylinder heads and Bosch K-Jetronic fuel injection to make 455 horsepower.

Desperate for cash, Lamborghini’s management branched out, bidding on a series of engineering projects, including building a military vehicle for the Saudi army. When that project fell through, Lamborghini put the LM002 truck into production in 1986 as a luxury off-roader using a version of the 5.2-liter V-12. Lamborghini’s association with another alternate form of transport, boats, dates back to 1969, when Ferruccio installed a pair of the company’s V-12s in his personal Riva Aquarama speedboat. So, in 1984, Lamborghini began supplying engines to offshore powerboat racers, the displacements rising to 9.3 liters and the output to around 900 horsepower.

Lee Iacocca became the company’s next angel, ordering Chrysler to purchase Lamborghini in 1990 and flushing it with money. The resulting Diablo replaced the 16-year-old Countach and added computer management to the now-5.7-liter V-12 to make it compliant with U.S. emissions and onboard diagnostic rules. The block grew upward with the increased displacement and also split around the bottom. A bolt-on girdle with integrated main-bearing caps was tied together in one casting for greater strength, replacing the original’s individual bearing caps. Programmed in-house—long a source of pride for the company—the Lamborghini Injectione Electronica (LIE) modules gave the V-12 precise control of the spark timing and port fuel-injection system with circuit boards sourced from an Italian supplier that made computers for gym equipment. The Diablo’s horsepower (472) and torque (428 lb-ft) rose accordingly.

Eventually, the Diablo’s V-12 punched out to 6.0 liters and made 550 horsepower with help from a two-stage variable-cam-timing mechanism. But Chrysler walked—no, ran—away in 1993, leaving Lamborghini in the hands of an Indonesian conglomerate that barely kept the company afloat until it was scooped up by Volkswagen’s Audi subsidiary in 1998. Still, the last remnants of the old V-12 design—mainly its upper crankcase—soldiered on for another dozen years, through the introduction of yet another new scissor-door Countach descendant, the Murcielago. The final 6.5-liter iteration in the Murcielago LP670-4 SV finished the engine’s long run making 661 horsepower, more than twice the output of Lamborghini’s first V-12.

The original V-12 (and its descendants) outlasted its patron, who died in 1993. His engine owed its longevity to its flexibility—to some extent a byproduct of early decisions that may have been entirely ego-driven—as well as a chronic lack of funds for replacing it.

The engine in all its forms went into just over 12,000 cars, and the factory has put many parts back into production to make it easier to keep running the 85 percent of them thought to still be roadworthy. The Cavaliere never did crush the Commendatore, but Ferruccio Lamborghini firmly inscribed his name into automotive history, a name often spoken in reverence to the music of 12 trumpets wailing.