Media | Articles

Lada 111 Tuning: The toughest horsepower that was ever earned, Part 1

Not long ago, I reached a new milestone of maturity: I changed the timing belt on a non-interference engine. I’m not sure what came over me. Perhaps it was the chilling thought of explaining to the Polizei here in Germany that, due to maintenance oversight, I was blocking the only route between two major Stuttgart suburbs. Or perhaps things were getting too easy? During the mindless garage job, I was watching some internet videos, corrupting myself with a German tuning YouTube channel called Halle 77. It got me thinking about the challenge of optimizing such a motor; why is a 1.6-liter 16-valve motor only turning 6000 rpm and making 94 horsepower? How hard could it be to unlock a bit more Leistung?

First challenge accepted: finding parts. Down the rabbit hole I went, debit card and Google Translate in hand. OK, so I’ll be looking for some распредвалы for my лада 2111 with the 16V мотор. (That’s “camshafts for my Lada 211“, naturally.) Many search results followed, a clear benefit of the sheer volume of such vehicles in former Soviet republics. And clearly there remains a following of tinkerers and hackers keeping them running.

Clicking a link on the first page of results linked me to a Lada tuning specialist that touted a whole package of parts guaranteed to pile an extra 50 horsepower (on top of my measly 94) for an unreasonably modest sum of money. For about 700 Euro ($847), I was promised a set of lumpy camshafts and adjustable gears, a cast-aluminum intake manifold with short runners and trumpets, a larger throttle, long tube headers, full 2-inch exhaust, and even a tunable ECU. Oh, and that’s including installation and dyno tuning at the outfit’s workshop in Moscow. At that price, it would be rude not to!

Sadly, despite my best mental gymnastics, I couldn’t justify a 50-hour-round-trip and also stick the landing. After a few translated emails and some help from my Russian-born German teacher, we identified the correct cams and ordered the parts for shipment, albeit with the installation fee conveniently transferred into a delivery cost.

They asked me before I placed the order: “Do you understand you will have to tune the ECU yourself?” Of course, I understand! How hard could it be?!

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

My second challenge was not technical as much as bureaucratic. The shipment arrived in two parts. The first was wrapped in a black plastic trash bag with the paperwork marked “GIFT.” (Customs headaches avoided.) I ripped through the protective garbage sack and duct tape, rifled through the cushioning Russian newspapers, and reveled in my mass of beautiful bargain speed parts. Ураaa! (Uraaa! i.e. Hooraaay!) The second shipment, a gigantic nose-to-tail exhaust system also wrapped in trash bags, wasn’t so lucky in transit. Waiting for my chance to fund a chunk of autobahn, the German tax office held my parts for ransom. This entrapment of goods initiates a long bureaucratic process involving many red-tape forms and friendly, process-oriented folks. It starts with a letter and ends with an in-person visit to the collection office three to four weeks later. In this case, a half-dozen phone calls were also necessary. But alas, my headers and exhaust were eventually released for the sum of 20.78 Euro ($25.14) and my governmental challenges overcome … for now.

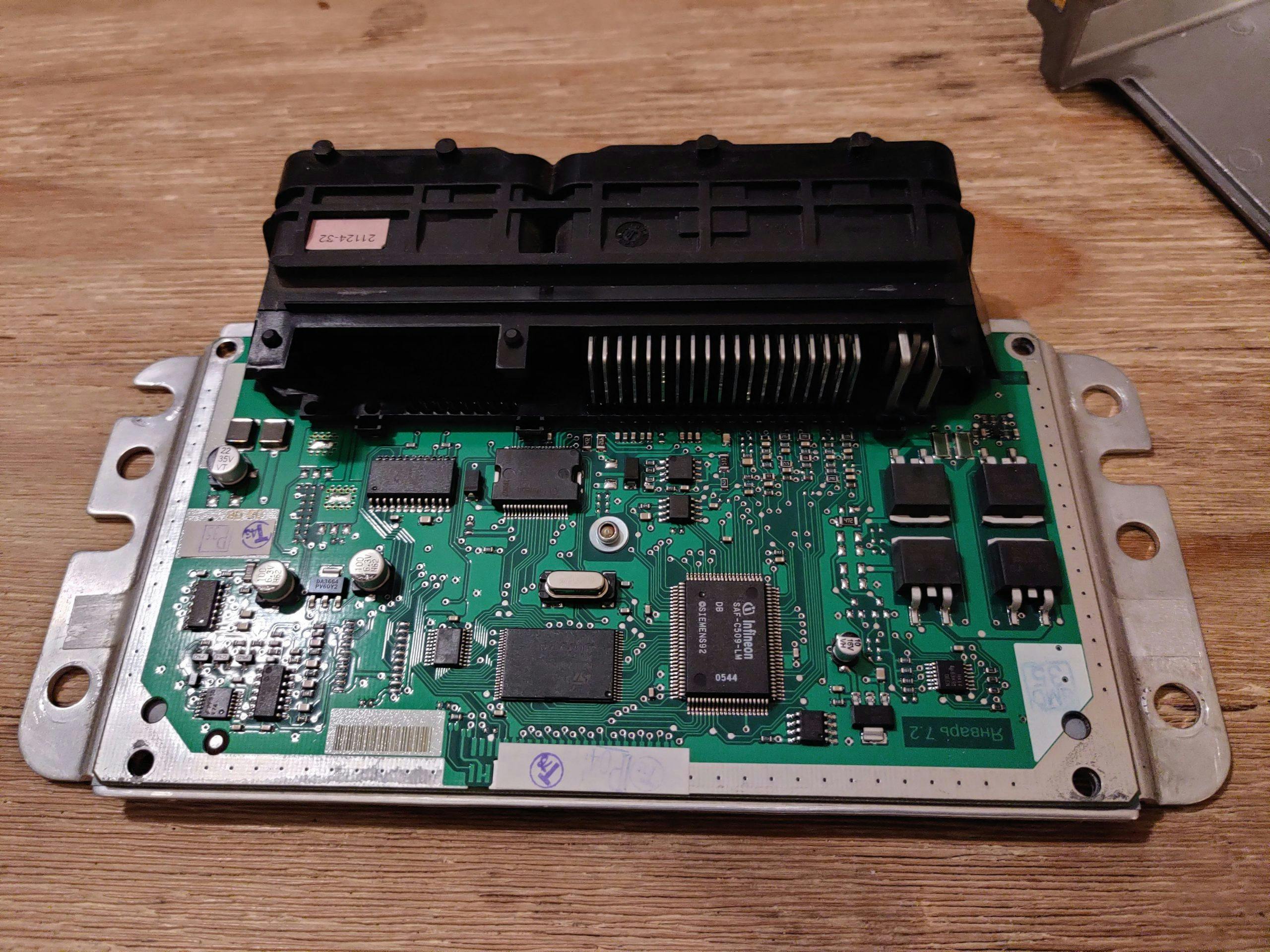

The delay meant I had some time to play around with the Lada’s electronics. It kicked off with my attempt to obtain calibration access to the ECU, the mighty январь (Yanvar, i.e. January) 7.2 complete with launch control. On my way out the door for work, I was feeling rather comfortable with risk. I took my new ECU under the arm with my backpack over my shoulder. Three Phillips screws and a bit of prying later, the new ECU was in place in all of 60 seconds. Of course, this was all the proof I needed that any removal could be executed lightning-quick, even under the duress of honking cars behind me. Should that become necessary.

Expecting the worst in terms of base calibration, I was shocked that the motor came to life immediately. Room for improvement? Surely. But I did manage to commute to work, and I even made it back home again. Expectations far exceeded!

Hurdles arose when I researched how to fiddle with the calibration on the ECU. Here, the prior technical and bureaucratic challenges turned into a bizarre combination of linguistic blockers, social media profiles, and Windows 98. After adjusting my laptop’s language settings and practically downloading the entire internet circa 2001 in mysterious ZIP files, I had nearly all of the software tools installed. Nearly. Ultimately the easiest path (can’t believe I’m saying this) was to join a Russian social media network and make a friend who would send me the remaining programs. Downside: Part of the deal was that I also had to buy an ECU from him. And now I may also be on a watch list that makes it difficult to board an airplane. Anyway, 100 Euro ($121) later, I had another trash-bag wrapped “gift” on my doorstep.

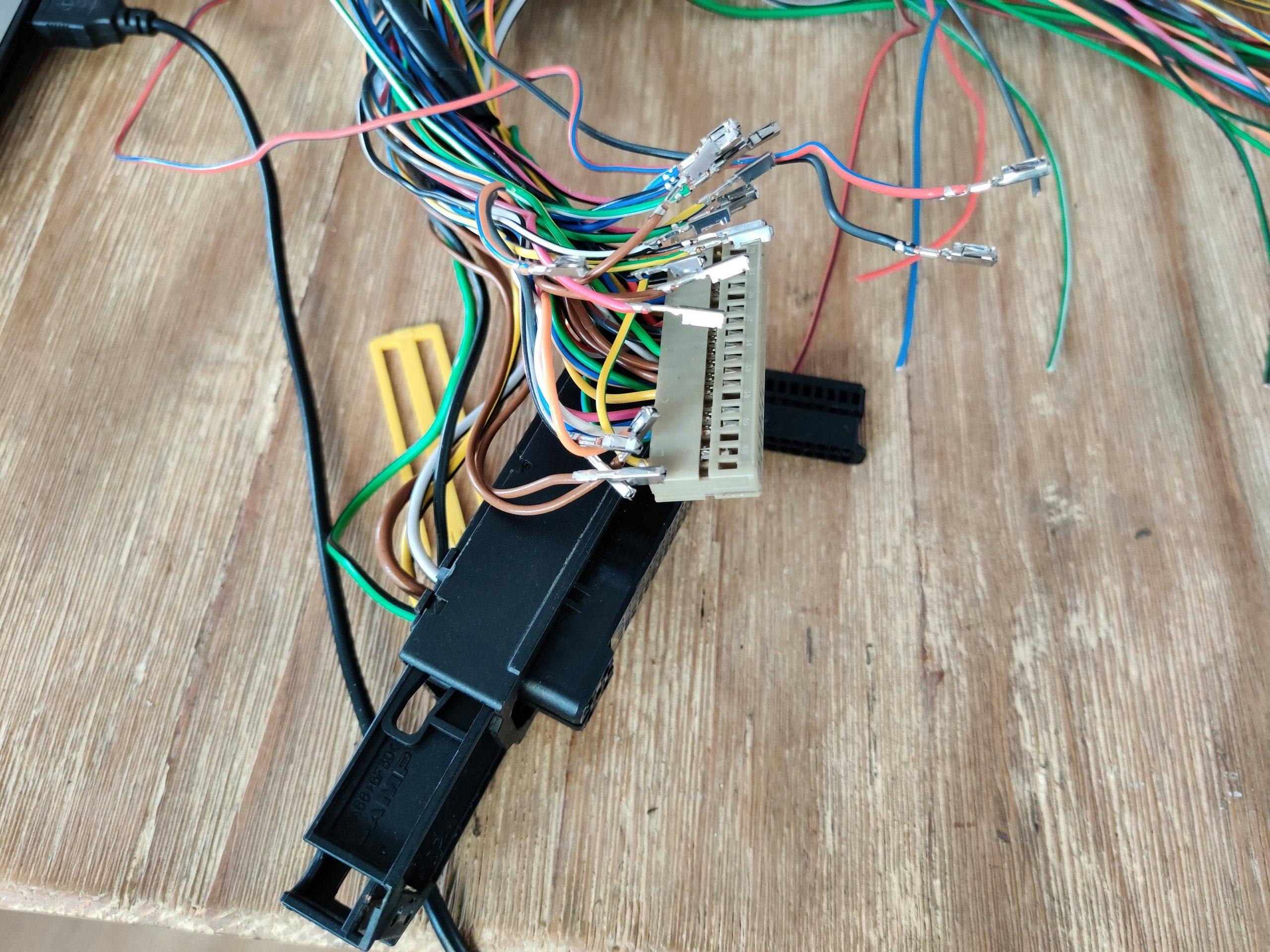

If I were to flash an ECU on my kitchen table, things had to proceed as quickly as possible, for cohabitation reasons. I quickly hit up my local classifieds and found a guy hacking up a 16V Lada Kalina, which has just the right ECU header connector for a snazzy bench harness. He also had some mudflaps and a shift linkage rebuild kit that I needed. Can a comrade get any luckier? About a whole day after unwrapping more trash bags full of Lada parts, soldering in some resistors, and repinning the harness, I found myself (somehow) connected and jamming zeroes and ones down this thing’s e-gullet. A quick test of the car connection through the OBD port worked, and with the help of a children’s poster of the Cyrillic alphabet, I was awash in the bliss of full calibration mode. Easy peasy.

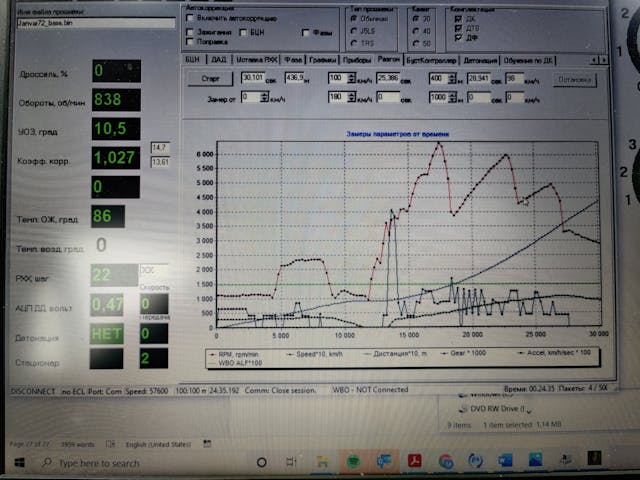

Now live, I used my laptop as a data logger in conjunction with my sketchy tuning tools and was able to log some baseline data. Dyno time being expensive, I elected to use 0–100 kph (0–60 mph) and top speed as my chief metrics. I not-so-quickly ripped off a smoking 12.6-second 0–100 kph time and later a 207 kph (128 mph) top speed at 5700 rpm with the aid of a huge downhill on an unrestricted autobahn section.

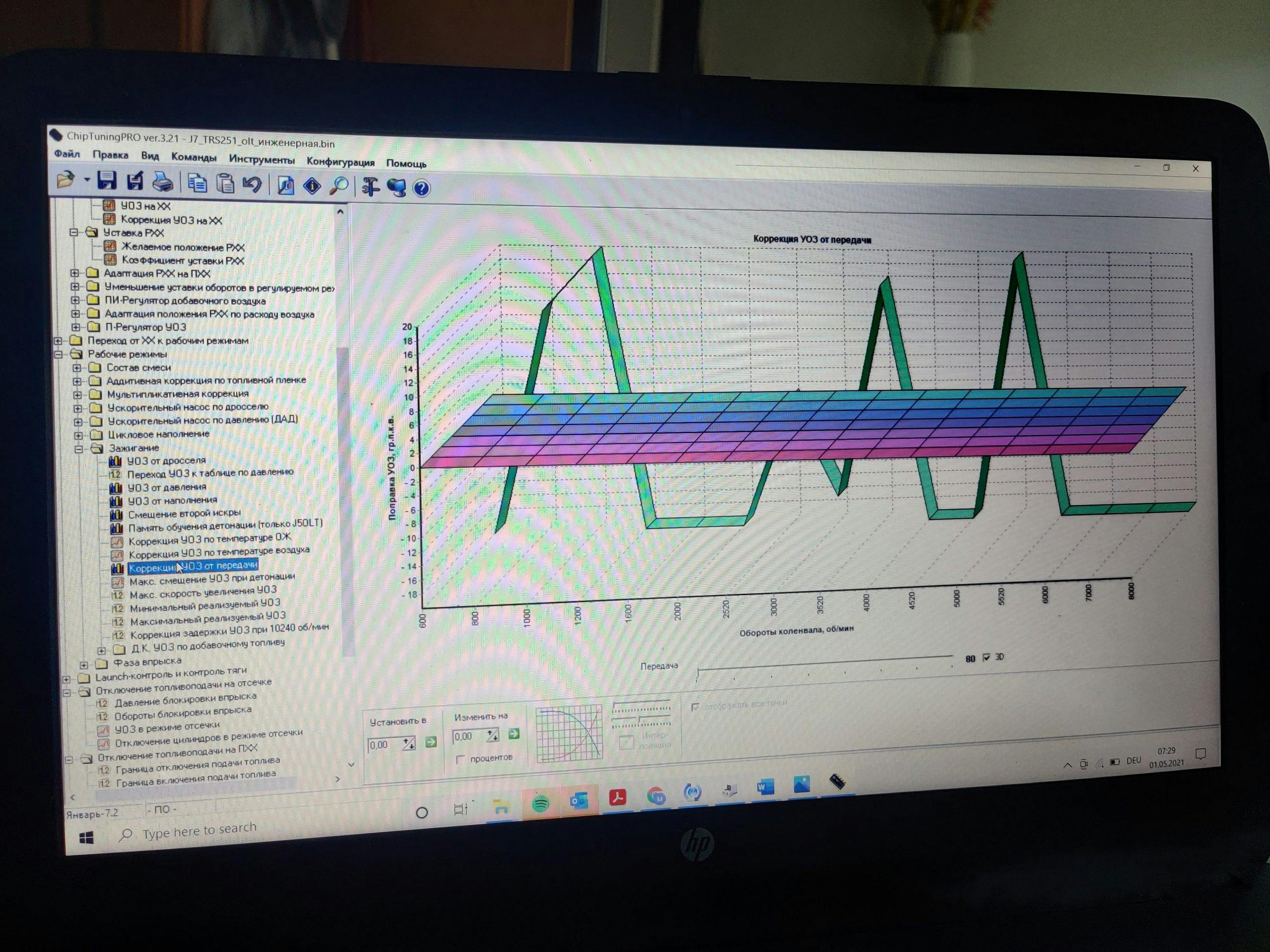

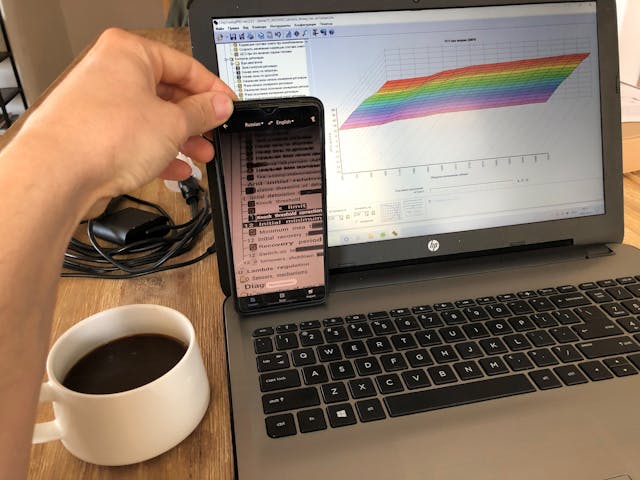

Back on the dinner table with Google Translate hijacking my phone’s camera, I was able to find the rev limiter in the ECU and promptly move it into valve float territory. While I’m in there, I conservatively added 5 percent fueling and recklessly chucked 6 degrees of ignition advance in across the board. I topped it all off, literally and in physical-land, by filling the last half of the tank with 98-octane fuel. It’s got a knock sensor, so who cares? My quick repeat test yielded a two-second drop in 0–100 kph time with the 1–2 shift point a full 1200 rpm higher!

Once I knew the ECU could be calibrated to reflect my planned mechanical changes, it was full speed ahead. No point in optimizing when I have a collapsed cardboard box full o’ parts to install.

Things were finally starting to ease up. First step was fitting the beautifully trumpeted (but poorly cast) intake manifold. Recognizing that my LPG fuel setup Ts into my existing manifold, I had to redrill the new one to fit the nozzles. I decided to keep the LPG system in place; it’ll just need recalibration at a later date. It’s easier than changing the car’s paperwork (again) to reflect another fuel system change, and I’ve had enough paperwork. Now with the manifold bolted into place, it became clear the valve cover would need some modification to accommodate the extremely short runners. A quick bit of hacking and plugging moved the PCV to the other side of the cover. Good stuff.

Next up came the removal of the factory exhaust and manifold for replacement with the complete Stinger setup. Wanting to limit the number of construction zones, I’ve decided to wait until the manifold and valve cover get back from powder-coating and finish fixing the window regulator and shift linkage in the meantime. My strategy is to collect some data on the new intake manifold and exhaust and retune, if necessary, before nasty bump sticks go in.

A good plan, right? Oh, and I ended up connecting with that German tuning YouTube channel, Halle 77. Just got my email confirmation: Dyno date confirmed in just a handful of weeks, and a mere five-hour drive away. What could go wrong?

***

Matthew Anderson is an American engineer who relocated to Germany a few years ago for work. In his spare time, with reckless abandon, he pursues a baffling obsession with unexceptional Eastern Bloc cars. We don’t ask him too many follow-up questions.