Media | Articles

In praise of the parts car

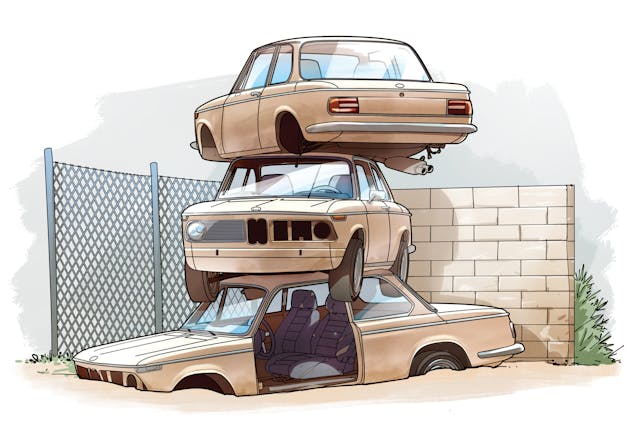

If you find an appropriate parts car (and have the space for it), the lure can be irresistible. From small stuff like clips and fasteners to bigger items like interior bits and drivetrain components, it’s a beautiful thing to simply walk out back and pull a needed widget out of your personal one-car scrap yard. Plus, if the parts car is largely intact, even when you’re not pulling stuff off it, it can be valuable as a reference for tasks such as correcting wiring that may have been modified on your running car. The key is having the space. Many of us don’t. In the late 1980s, I parted out several BMW 2002s and E9 coupes, and to some extent, I’m still living off the parts stash. But I now live on 6600 square feet of land in suburban Boston. I haven’t had a parts car for 30 years. My driveway is packed to bursting with cars that I actually drive. It already looks like I’m running a repair shop. I think my neighbors might have something to say if that transitioned to looking like I’m running a junkyard.

In fact, this is why junkyards exist. They are really just other people’s parts cars on other people’s land, run as a business. The problem is that they aren’t quite the gold mines they used to be. Back in the day, a nearby junkyard might have had a 1971 Simca Bertone 1200 coupe exactly like yours, but the odds of them having one now are essentially zero. Junkyards are subjected to the same space pressures and land costs that you are, at a larger scale and with much tighter regulation. Anything that doesn’t have demand gets crushed. So, if you want a specialty parts car, it has to take up your space, not theirs. Granted, there are marque- and model-specific specialty junkyards, and if there’s one near you, make friends with the owner. But their prices are often high, and shipping large parts is expensive.

The larger parts-car life cycle

A car may be relegated to parts-car status for a variety of reasons. On a vintage car, it’s usually rust through a frame rail or suspension attachment point that has progressed to where the car is unsafe to drive, and the cost of repair exceeds the car’s value. On a more modern and less rust-prone car, it could be an accident, a seized or overheated engine, or the cost of multiple needed repairs.

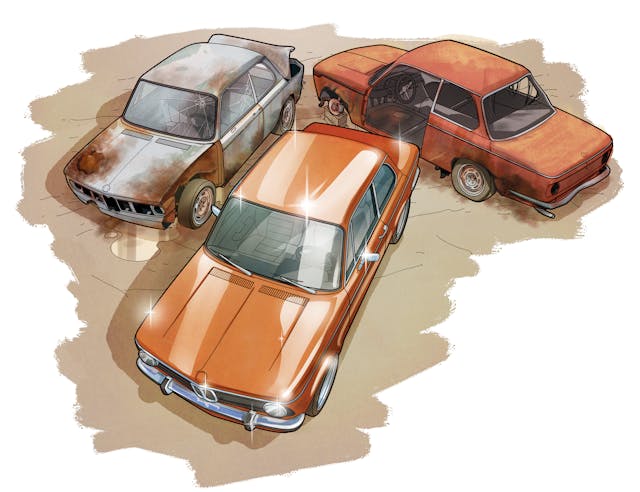

However, strange things sometimes happen that cause vehicles to be parted out before their time. In the vintage BMW 2002 world in which I operate, the five-speed gearbox, limited-slip differential, factory Recaro seats, and sport steering wheel from the late-1970s BMW 320is became highly sought-after retrofit components, and the cost of whole, intact, running 320is was so low that they were sometimes purchased and cannibalized before they were really in “parts-car” condition.

At the other end of the spectrum, a vintage car can appreciate so much that it becomes too valuable to part out in any condition. Long-hood (pre-1974) Porsche 911s certainly now fall into that category. And I’d be shocked if there’s a Split-Window ’63 C2 Corvette parts car anywhere in the country.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Sometimes, which car is the donor and which is the recipient unexpectedly flips around. I have friends who have bought parts cars sight unseen and, once they laid eyes and hands on them, found that they were more solid than the car they already owned. Sometimes it becomes more a matter of borrowing parts and trying not to do anything irreversible to the “parts car,” knowing that its rising value will eventually make it viable if it stays intact.

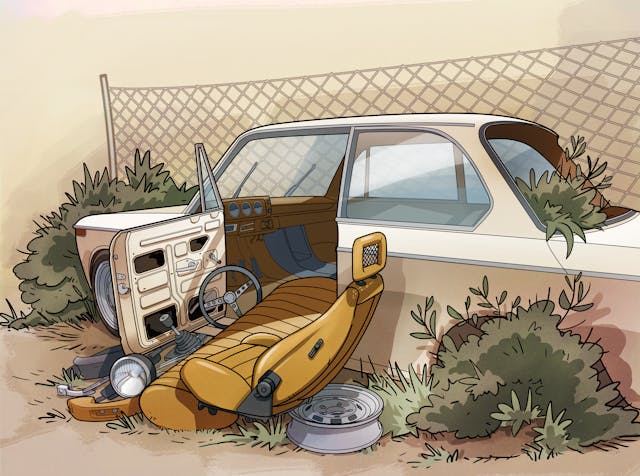

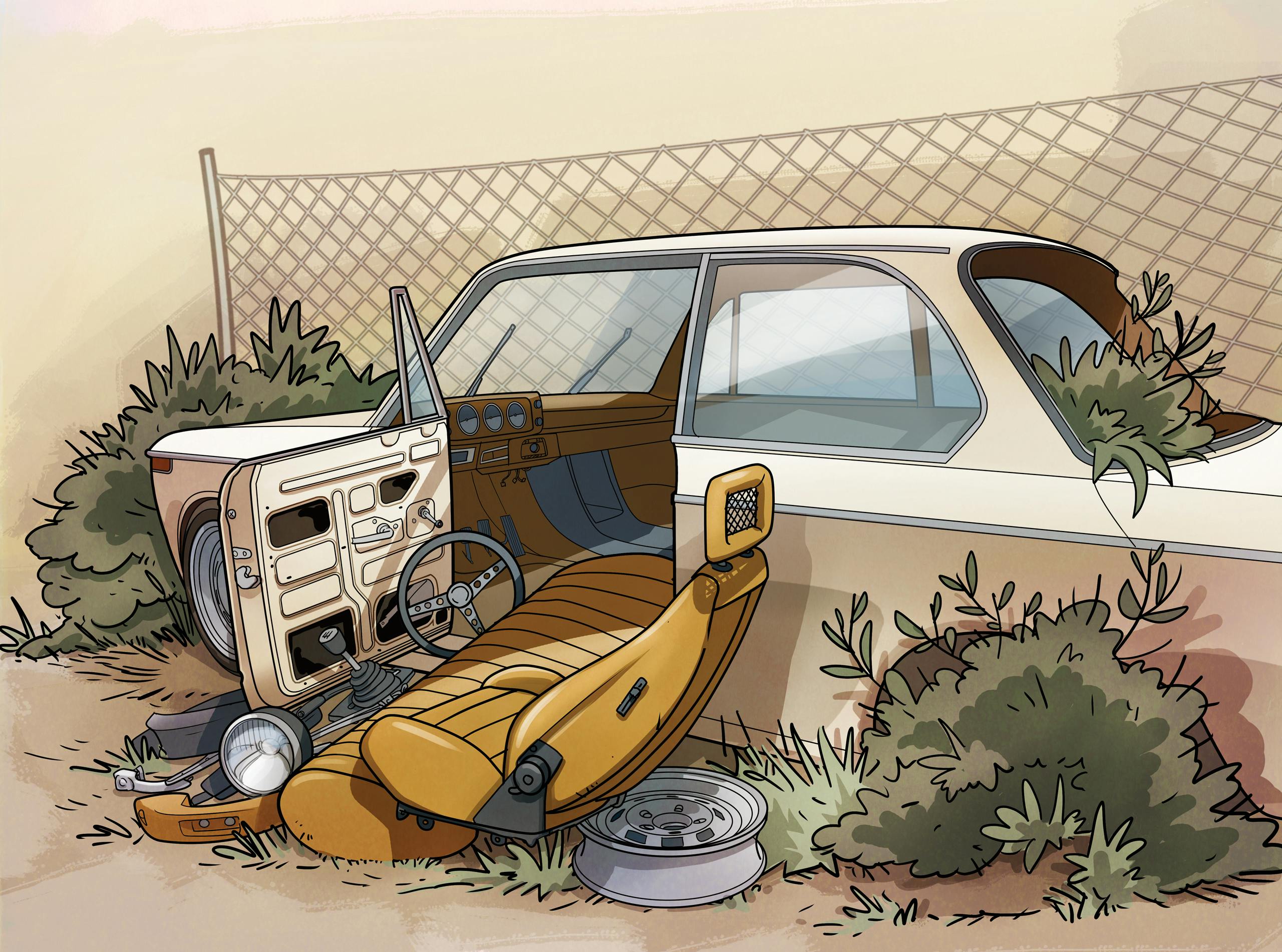

The perfectly sized parts box

One of the things you learn with a parts car is that it is the perfectly sized container on wheels for its parts. What’s more, each part you need is exactly where it’s supposed to be; you don’t have to go rooting about to find the steering column universal joint that you know is there somewhere. It’ll be right where the factory put it. If the car is rusty and you think that dismantling it and having the body hauled off for scrap will make the volume of parts smaller, you’re in for a rude awakening. Take a car apart and try to store the parts in your basement or shed. Kablam—the volume absolutely explodes. The doors, trunklid, windshield, seats, drivetrain, and subframes aren’t simply going to hover in their former locations in space. They have to go somewhere, which generally means on the floor. Which generally means that nothing can go on top of them. All the little stuff has to go in boxes. The boxes can be shelved, and you might think that this organization is saving space, but it never works out that way. I guarantee you that it’s never going to be anywhere near as space-efficient as leaving the car intact.

Know what you want out of a parts car

You may own a model that’s so rare that any reasonably priced parts car is worth pouncing on, even sight unseen. But for more common makes and models, you can sometimes be choosy. Are you looking for something in particular? A good replacement engine? A manual transmission swap? An uncracked dashboard? Aftermarket sport seats? Or is it just assorted parts? Be aware that condition tends to be systemic—that is, it’s highly unusual to find a car that was subjected to so much weather that it’s now an unrestorable rusty hulk but with a near-mint interior.

An identical parts car is almost a unicorn

Unfortunately, history does not record the first parts car, but I’d wager it was a Model T Ford, given the car’s 19-year production span and low cost. However, long production spans create a problem: The components in the parts car may not be the same as in yours. You’re probably already aware of your car’s external facelifts, different options, and various trim levels. You may own an early car and want to find a car whose VIN is no more than two digits away from yours, but it may not be possible; you may find yourself buying a more affordable later model, figuring that even if the interior isn’t identical, at least most of the mechanical components are. Although it’s not a sin against nature to, for example, transplant a crack-free dash or a set of unripped seats from a later car into an earlier one, just be aware that that’s what you’re doing.

The modern engine swap application

One motivation for wanting a parts car is the modern engine swap. For example, in my BMW world, it’s common to swap the 208-hp engine with fuel injection, digital engine management, and five-speed gearbox from an early 1990s 5-series BMW into an E9 (the lovely 2800CS and 3.0CS coupes from the early ’70s), replacing the older carbureted engine and four-speed. Although you can source the parts individually, the trick thing to do is find a running donor car. That way, you can hear the engine run, evaluate its condition, make sure it doesn’t burn oil, do a compression test, and be certain that you have not only the engine and gearbox, but also the electronic control unit, an uncut wiring harness, every sensor, and all the ancillary engine accessories (power steering pump, A/C compressor, etc.) needed for the conversion. In this case, once you’re done, you would have little use for the rest of the car.

Zombie parts cars that may rise from the dead

You may see a car advertised as “for parts only.” People do that for a number of reasons. On a vintage car, it may be an honest statement of the car’s rotted condition. If you see a newer car that doesn’t seem all that bad and you start to think about buying it to bring it back from the brink, you need to be careful. In a state with strong consumer protections, so-called “lemon laws” may allow the buyer to return the car to the seller if there are undis-closed issues or if the car doesn’t pass inspection. Thus, the “for parts only” warning, combined with withholding the title, is sometimes employed by sellers as a means to ensure the car doesn’t come back to them. If you’re think-ing about reviving a parts car, be certain to see if it has a salvage title. A “repairable brand” salvage title is one thing, but if the salvage title says “parts only,” it may not be possible to re-register that VIN in your state.

Making money on the parts

It might be tempting to buy a parts car to get the one or two things you know you need, then try to make the money back by parting the car out. This is rarely a winning proposition. I haven’t parted out a car recently, but I’ve purchased several parts hoards and regretted it every time. You probably know from experience the parts for your model that have a high value. Typically, certain exterior parts like grilles, chrome bumpers, and taillights, and interior parts like dashboards and seats, have a high value if and only if they’re in excellent condition. Few people want them if they’re cracked, rusted, or pitted. On a big part like a bumper, it’s time-consuming to respond to an interested party, box and weigh the part, and quote shipping, only to have them bail out when they see the cost. If you don’t want to keep the parts car around, the smart thing to do is to identify and move the handful of small, light, high-dollar parts, then sell the entire thing for whatever you can get for it. You might leave a few dollars on the table, but you’ll save yourself a lot of grief and prevent your basement from being filled with parts that sit there for years.

Self-identifying as the Grim Reaper

The two BMW E9 coupes I parted out 35 years ago were cars that are now worth over a hundred grand in restored condition. However, one had been T-boned and the other was long dead, rusty, and picked over. I didn’t hasten their demise, and to this day, I pull window motors, switches, and assorted fasteners out of the stash. There was one car, though, where I do regret my actions. It was a 1971 BMW 2002ti. This was the dual-sidedraft-carburetor predecessor to the fuel-injected 2002tii, never commercially imported into this country. It had rust, but it wasn’t rusty. There is zero question that, nowadays, this car would be at least put back into service, if not restored. But I cannibalized it, and I do feel bad about it. However, the cylinder head, Weber 40DCOE sidedrafts, intake manifolds, front struts, and the entire upgraded braking system all went into another 2002 that I still own. Perhaps that somewhat ameliorates the nature of my sin.

In closing

The economics are simple. If you need assorted parts for your vintage car, and you find a nearby inexpensive parts car that has them, and you have the means to drag it back to your property and the space for it, you probably won’t regret buying it. It’ll likely pay for itself several times over. Even if you don’t need a high-dollar item like a cylinder head, other items like assorted brackets, little mesh screens that are no longer available, original hose clamps, and fine-threaded M12 bolts that are exactly the right length are worth their weight in ZDDP additive. But if you do reach the point of having it hauled off for scrap, bow your head and smile when you recognize the parts from it that sojourn on in your baby. That car gave its life so that others of its kind may live. Show a little respect.

***

Rob Siegel has been writing the column The Hack Mechanic™ for 35 years. His eight books are available on Amazon or directly from Rob at robsiegel.com.