Media | Articles

How to keep turbos spinning smoothly

Last time, we looked at the basics of a classic turbo installation but as ever with these things, there’s more to maintaining the health of a turbocharger system than only caring for the turbo itself. The control system that ensures everything operates like clockwork will benefit from a health check and preventative repairs as early turbo-era cars age.

With a very early system, like a mid-1980s Porsche 911 930 Turbo (1975–1989), the wastegate, which releases exhaust pressure when maximum boost is reached or the driver lifts off the throttle, is completely mechanical and resembles a small, single-cylinder engine containing a single poppet valve, spring, and diaphragm. Boost pressure acting on the diaphragm opens the poppet valve against the spring and exhaust pressure is released into the atmosphere via a small silencer.

In that case, the boost pressure is controlled only by the strength of the spring. On an unrestored 930 Turbo I bought a few years back, the wastegate was in a sorry state. One of the four studs holding it to the exhaust manifold had broken, the wastegate casting was cracked at the mount, the exhaust was blowing and the boost was low. The fix was to drill out and replace the broken stud along with the other three and fit a new Tial Sport wastegate.

Admittedly, it wasn’t an original feature but what’s more important—total originality or a totally healthy engine? I wanted to be 100 percent certain it would work perfectly and protect the engine. Because while 930 Turbo engines can go on forever, if things should go wrong, they cost a fortune to rebuild.

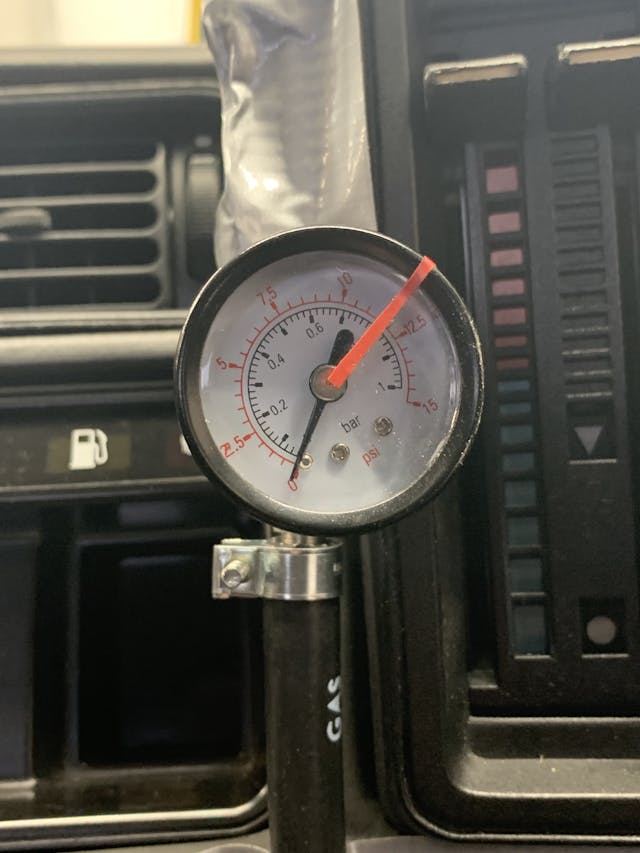

As the 1980s progressed things got a little more sophisticated and the RS Fords, Saabs, and Audis used an electrically-controlled Amal solenoid valve to control an external wastegate actuator triggered by the ECU. The Ford ECU in turn monitors inlet manifold pressure via a MAP (Manifold Absolute Pressure) sensor. On the Sierra Cosworth, the valve allows boost pressure to be fed to the actuator to open the wastegate and it connects the inlet manifold to the air filter box to silently release boost. Those who like the “pfffft” sound of the boost being dumped prefer to fit dump valves, which vent straight into the atmosphere. Checks on the boost and wastegate function are made by temporarily teeing into the compressor pressure hose and running a pipe into the cabin ending in a pressure gauge, taped where you can see it.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The solenoids are reasonably plentiful secondhand and can be checked by connecting them to a 12-volt feed and blowing into the ports, of which there are three. One is connected to the wastegate actuator, another to the turbo compressor housing, and the third to the air filter box. When the ECU detects that maximum boost pressure has been reached, or the driver has lifted off the throttle, it activates the solenoid valve and two things happen: It allows pressure from the manifold into the wastegate actuator to open the wastegate and kill the boost, and it opens the other two nozzles so that pressure from the turbo’s compressor is released into the airbox.

While turbo controls vary, the principle remains the same. Boost pressure must be responded to and whether it be by the compression force of a spring, like in the Porsche 930, or electronically, exhaust pressure has to be diverted away from the turbocharger turbine to allow inlet pressure to simultaneously return to “natural.” With that in mind and a decent maintenance manual for the car, it should be possible to keep most classic turbo systems in good shape without busting the bank.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

Via Hagerty UK

I changed the blowoff valve on my Supra. Tiny and in an area getting high heat from the engine/turbos plus plastic parts internally. I didn’t want them to break and get sucked into the motor so HKS blowoff valve and no worries.