Media | Articles

How the mid-engine Corvette’s LT2 V-8 improves on the LT1

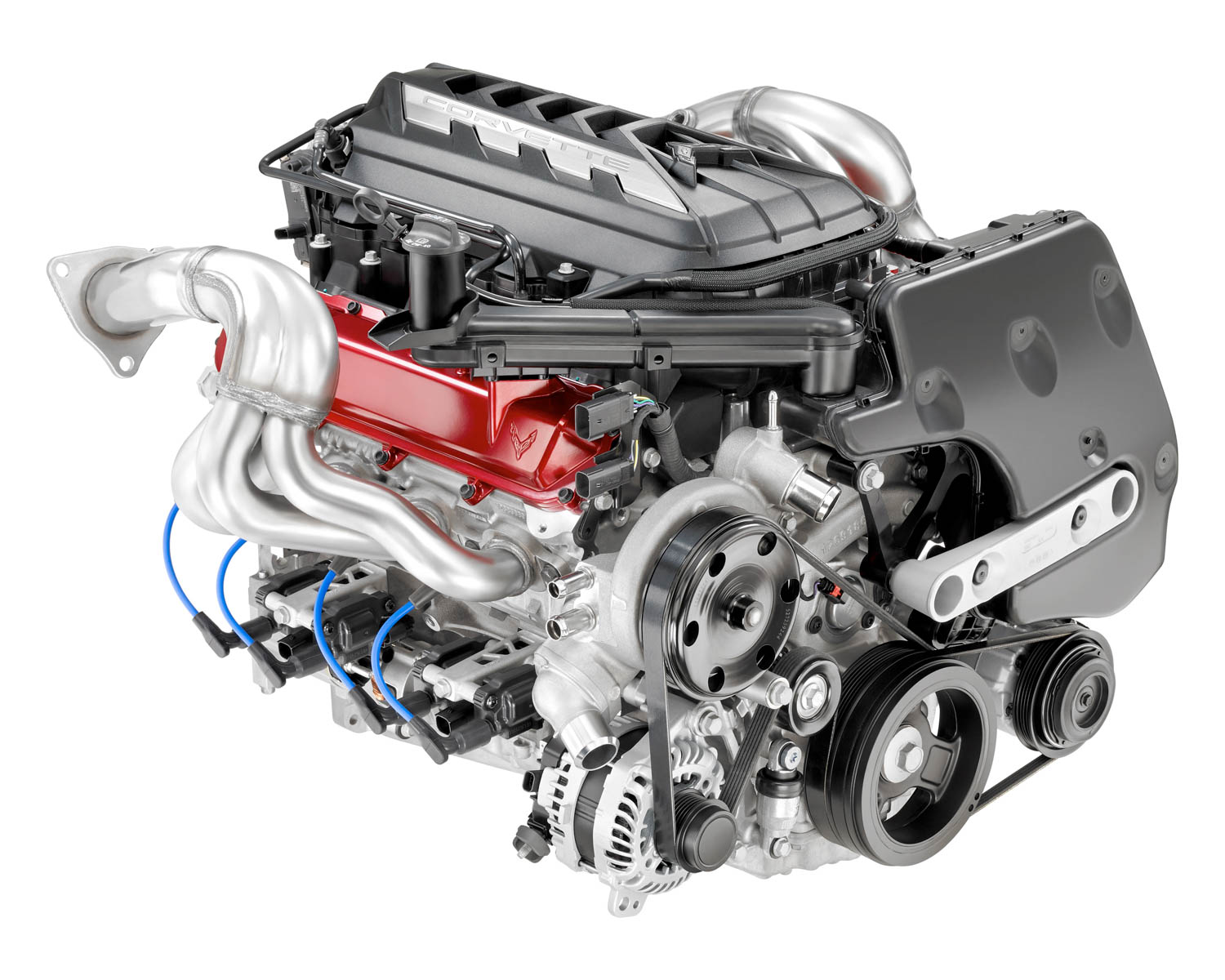

The mid-engine 2020 Corvette is finally here, and as expected it retains the venerable Chevy small-block as its base engine in the Stingray. At first glance it appears to be almost a direct transfer from the current C7-generation car; looking a little deeper, though, Chevy has actually made some significant changes to the Corvette small-block.

While the displacement carries over and the pistons appear to be the same size, the supporting components have been updated for a mid-engine application. Some of those updates are responsible for the output increase from 460 to 495 hp in the first-ever mid-engine Corvette.

Moving an engine from the front to the middle of the car often requires significant modification. Most manufacturers will want the center of gravity to be as low as possible, taking the greatest possible advantage of a mid-engine layout’s handling properties. Lowering an engine often means modifying exhaust manifolds; while the engine in a front-mounted car can send the manifolds to exit more or less directly below the block, the mid-mounted application specifies that they need to exit behind (and almost slightly above) the heads. This type of configuration allowed more efficient routing than used on the compact, cast log-style manifold that is present on the current LT1 engine.

Chevy took this opportunity and designed a large-volume, tubular manifold that appears to be comprised of equal-length runners. This not only solved the packaging issue but also resulted in more power being produced helping with the 35-hp bump on the Z51 performance-exhaust-equipped cars.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Since the engine is mounted so low, the current wet sump oil pan was out of the equation, with a new dry sump system in its place. While dry sump configurations have been used on higher performance trims of the Corvette in the past, this is the first time that one shows up on the base car. This system is also novel in that it is mostly self-contained. The whole system, which includes the tank and three scavenge pumps, is mounted directly on the engine—a departure from previous designs which had an oil tank mounted somewhere on the firewall with lines going to the oil pan.

The main advantage of dry sump oil system is the ability to maintain engine performance while driving the car at high cornering loads, but another big advantage of a dry sump system is that drag and windage of oil are reduced in the oil pan, since the scavenge pumps pull a certain quantity of oil away from the crankshaft. In some cases this can cause an increase in engine efficiency and can contribute to a power increase if the vacuum level in the crankcase is increased as well.

Just these changes on their own would warrant the designation change from LT1 to LT2 for the new engine, but changing any single component on an engine usually begets more changes on top. Keen observers will notice that the coil packs on the LT2 have been moved from their previous location on the valve cover down to some cast aluminum brackets on the side of the block. This was likely done in order to extend the life of the coil packs and keep them away from the headers, but it also had the nice side effect of allowing for completely clean valve covers that can now be used as a decorative portion of the motor. Other changes on the outside of the motor include a new water pump along with other moves on the accessory drive layout in order to compensate for the for the dry sump components that are now mounted on the front of the engine.

Internally, the engine stays much the same. It retains the same 103.25 millimeter bore and 92 millimeter stroke of the LT1 engine along with the same 11.5:1 compression ratio. The compression stays the same since the cylinder heads use the same casting as the LT1 and contain the same 54 millimeter intake valves and 40.4 millimeter sodium-filled exhaust valves. Since the compression ratio is the same, it is no surprise that the 59-cc combustion chamber volume is also retained. The last piece that appears to be a carryover at least in size is the throttle body, which at 87 millimeters is an exact match for the unit on the LT1.

That throttle body is mounted facing rearward in the C8 and feeds a new intake manifold. The intake routing also takes advantage of the mid-engine placement as the Stingray breathes through a massive oval air cleaner and a short, cylindrical intake tract that, unlike the C7, doesn’t have to be contorted to reach cool air in front of a radiator.

Taking advantage of the newfound airflow capability afforded by the intake and exhaust is the camshaft, which has been swapped for a more aggressive unit with increased duration. Combine this new camshaft with the improved airflow, along with a new ECU, and it’s not hard to see how the horsepower and torque increases over the LT1 were achieved.

These updates move peak horsepower a little further up the powerband—the 495-horsepower figure hits at 6450 rpm on the Z51 performance exhaust cars, while the older LT1 would reach its peak of 460 horsepower at 6000 RPM on the same trim. Although the peak horsepower is higher up in the powerband, it is likely that the new engine produces the same or more power as the LT1 at that 6000 rpm. The new camshaft simply enables the engine to be revved up higher without losing efficiency.

All of these features, combined with the new dual-clutch gearbox, help to propel the Z51 variant of the new Corvette to 60 miles per hour in less than 3 seconds and give it capability far beyond those drag strip runs. The new dry sump system makes it ready for a road course right out of the box. The engine offers a bit for everyone, as it has many modern technological advances but still keeps things a bit old school with pushrods moving each pair of valves per cylinder.

Before long, we’ll see tuners cranking these engines way up, just like they’ve always done.