Media | Articles

How my 1987 CRX left its mark on the Honda mod community

Remember when, 10 years ago, fuel prices were about double what they are today? Prime time to own a 1969 Chevrolet CST/10 with its Quadrajet huffing fuel, of course! Even better, an ideal vehicle for pizza delivery. A situation where you’re driving in traffic all day, pouring fuel with each blast back up to speed, and then banking that consumption on the day’s income … it worked. For a time, anyway. But as I entered college, I wanted something more efficient and fun to drive. Little did I know that this machine, and the work I’d put into it, would have its own legacy after I had moved on to other projects.

I spent hours on Craigslist looking for a small, four-cylinder car to keep some spare cash out of the fuel tank and into my pocket. A small footprint and manual transmission was strictly required, but beyond that, the options were open. One tire-kicking evening I spent at a trailer park in Cleveland, Texas, eyeing up a Geo Storm with what turned out to be a slipped timing belt, but eventually something in my price range of “this week’s tips” appeared: a dark-blue 1987 Honda CRX.

The cheese-wedge Honda is one of the smallest vehicles to have ever been sold for U.S. roads, some 10 inches shorter than an NA Miata, even. The CRX rid itself of a conventional coil-over-strut configuration for the front suspension in lieu of torsion bars in order to lower the overall height of the hood, since the strut tower could be set lower in the chassis without having to also support the spring. The fastback profile and short wheelbase of the little Japanese hatchback gave it an undeniably fun feel on the road, and its three trim levels reflecting an array of drivers—the Si for enthusiasts, the HF for the fuel thrifty, and the catch-all DX—tailored the CRX to a wide variety of situations and use cases.

From the Pulitzer-winning photos in the ad for my would-be car, however, it was impossible to tell which flavor of CRX was waiting on the other end. A description that could be best described as “aggressively vague” complemented the equally inscrutable visuals, but the offer came down to this: The CRX in exchange for $1000 … or a rear axle for a 1996 Isuzu Rodeo.

Within a few phone calls, I had located one such axle for the ripe price of $200 at Charlie’s Salvage, picked and ready on the counter. After talking to the CRX’s owner, my dad and I piled a bunch of tools into the trunk of his Grand Prix, turning first towards Tomball before heading west to Austin.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

As promised, Red, the keeper of the yard, had what looked to me to be an axle for an Isuzu Rodeo. With a few spins of the pinion to make sure it wasn’t seized or notchy, a fistful of dollars bought me the ticket to CRX glory. We kicked down the arm-rest hatch, strapped the axle in the back of the Grand Prix, and began for the capital city.

It’s hard to describe just how small the first-generation CRX is unless you’ve seen one in person. Bordering on fitting into the Kei car class, the car is truly the definition of a compact car, and it should come as no surprise that one is the foundation for Grand Theft Auto‘s “Blista Compact.” It was proportional to its 13-inch stamped aluminum wheels, and I could wrap my hand around the exhaust pipe without contacting it. In short, it was absolutely perfect for my needs. It ran well enough, and the seller was proferred the axle. Easy deal.

The thing to know about this generation of Honda are the pre-chambers brought over from IDI diesel engines to give these engines a lean and fuel-efficient mixture, sufficient to pass strict U.S. emissions regulations without needing a heavy, power-sucking, and expensive catalytic converter. The unique Keihin carburetor of these CVCC Hondas had to be puppeteered by an early-age electro-mechanical “computer” that would eventually tug at the Keihin’s various fuel cuts, solenoids, needle valves, and vacuum actuators through 50-plus vacuum lines in order to fine-tune the fuel curve.

The decline of this system would be the ultimate reason I sold the car, but after a little wrestling with the system and a much-needed valve adjustment, the CRX turned into a sewing machine for the time being. By now, I had finally figured out which flavor of CRX I’d bought: the frugal High Fuel economy (HF) model, with its additional weight loss. Curb weight floated around 1700 pounds sopping wet. Double-overdrive five-speed (fourth and fifth were OD; third was 1:1; it was slow in every gear). And most critically, a lack of rear sway bar. That last part matters.

Even with its minuscule footprint, the CRX HF’s handling was dump-truckish. It received the smallest front sway bar in the line-up, hollow too, while the rear was left without one in the name of weight savings. Coupled with the modest sidewalls used on the factory 13s, the car leaned over under any tough cornering. Understeer was the default behavior, which made the addition of a rear sway bar a no-brainer.

The issue was that this era of Honda suspension, which was made obsolete three years after the CRX’s initial release by the second-generation’s superior engines and double-wishbone suspension, had no developed aftermarket following; there wasn’t even an eBay special and trying to find one from an Si made finding needles in a haystack look like a good time. The forums had mentioned some were using a bar from later Civics, but I decided to grab my tape measure and head back to Charlie’s.

The CRX essentially sports a dead-beam rear axle, which made finding a compatible sway bar (via another junkyard donor with a similar suspension) a game of matching the width of the bar to see if its end links would end up near the CRX’s frame rails. I had found a few Civics that matched what the forums had mentioned, but their dual-wishbone suspensions used a very different sway bar shape and mounting location, baffling me as to how others were making them fit.

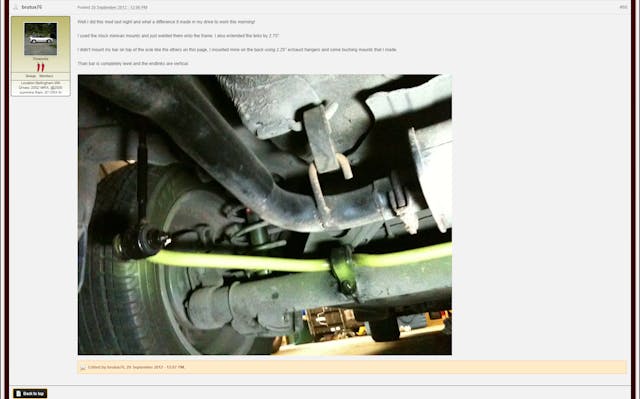

With a bit of wandering, looking under various cheap compacts, I spotted a Dodge Caravan Sport stacked on top of a Jeep Cherokee, which revealed the van’s crown jewel: its optional rear sway bar. Both the CRX and Caravan (somehow!) shared the same width between the main rails of the unibody chassis and, since that they both had dead-beam axles, mounting it to the suspension would be a case of matching the Caravan’s mounts to exhaust clamps.

I walked out of the junkyard with the sway bar and its mounts for $25 and got to work fitting and mounting the frame brackets from the Caravan onto the CRX so that the swaybar could hang before figuring its position on the CRX’s axle. A few new holes in the floor of the hatch allowed the brackets to be bolted easily from both sides, and I had found a few rubber plugs in my dad’s box-of-stuff in the garage to give it that OEM touch.

Red Pepper Racing was (and still is) the go-to source for everything third-gen Civic and first-gen CRX. It is a forum dedicated to Honda’s stuck-in-the-’80s generation of cars and wagons. The Caravan Sport’s sway bar had transformed the CRX’s handling and personality on the road, giving it more of the hot-hatch feel that the beloved Si had for the price of who-cares, so it became natural tutorial fodder in a forum thread on the swap.

I never thought much about my discovery after selling the CRX in 2011. In many ways, forums were what we had as social media, and countless tech tutorials and discussions have been created and forgotten about as the years moved on, or new projects pulled my meager memory banks elsewhere.

Years later, I began working for Hot Rod Magazine as a staff editor, and we were on the ground at Drag Week 2017 when I met a racer who had entered a bone-stock 1984 Honda Civic at the world’s fastest street car race. Slow junk like this used to be my jam! I struck up a conversation with the owner, Ian Christensen, during tech inspection, just trading stories about hard-to-find plastic fenders that cracked and nightmarish carburetor diagnostics, when I brought up throwing the Caravan sway bar into mine. The gears clicked in Ian’s head: “OH, you’re that guy!” Me? Guy?

Unbeknownst to me, during my detour from ’80s Honda antics, the Caravan sway bar had grown to become one of those de facto forum mods. The thread itself was still active with people building their own Caravan sway bar swapped Wagovans and Civics, just the same as I had with the CRX, and it had filled the gap that the aftermarket hadn’t for a price that was too good to pass up. That was true even for the models which came from the factory with a sway bar inside the dead-beam axle; the Caravan sway bar was now even infesting the sportier Preludes, Integras, and CRX Sis.

The CRX made me fall in love with small, sporty cars—enough so that when I flipped it for a small profit (to a local radio DJ that required the CRX’s shifter could be operated by his foot … just to say that he could do it) I immediately sunk the proceeds into a 1990 Miata. I had repainted the CRX, in the garage of a friend’s very-understanding father, to unitize its faded color. In it, in Nacadoches, I once got stuck waiting for a tow truck at a record shop for hours when the distributor died (“Listen to anything you want while you wait!”). Eventually, I ended up moving to Austin with the hatch stuffed to the gills with my belongings. There was a point where I bought a fuel-injected Si driveline from another Red Pepper member, but it ultimately ended up in the hands of a Lemons racers instead.

The chance meeting with one of my Caravan gospel readers was one of those unforgettable small-worldisms of car culture, especially online. People pass through different communities with changing projects, leaving automotive tangents along the way that eventually intersect again. You live, learn, and make friends along the way.