Media | Articles

Homegrown: “Garagefather” Dave Piontek has built dozens of visionary cars

Welcome to Homegrown—a new limited series about homebuilt cars and the ingenuity, diligence, and craftsmanship of their visionary creators. Know of a killer Homegrown car that fits the bill? Send us an email at tips@hagerty.com with the subject line HOMEGROWN: in all caps. Enjoy, fellow tinkerers! -Eric Weiner

By day he worked as an engineer at the Ford Motor Company but evenings and weekends were Dave Piontek’s time to shine as a master garage builder. An American “Garagefather,” if you will.

Even before he graduated from the University of Michigan with an engineering degree, he fearlessly converted his ’62 Corvair Spyder into a daunting autocross racer. Riding on a steel tubing frame constructed from scratch and topped with a crude but light aluminum body, Piontek’s first homebuilt was so quick that the club orchestrating his events told him his participation was no longer appreciated.

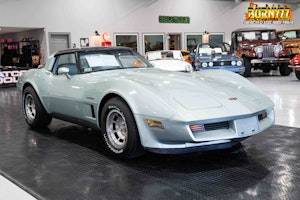

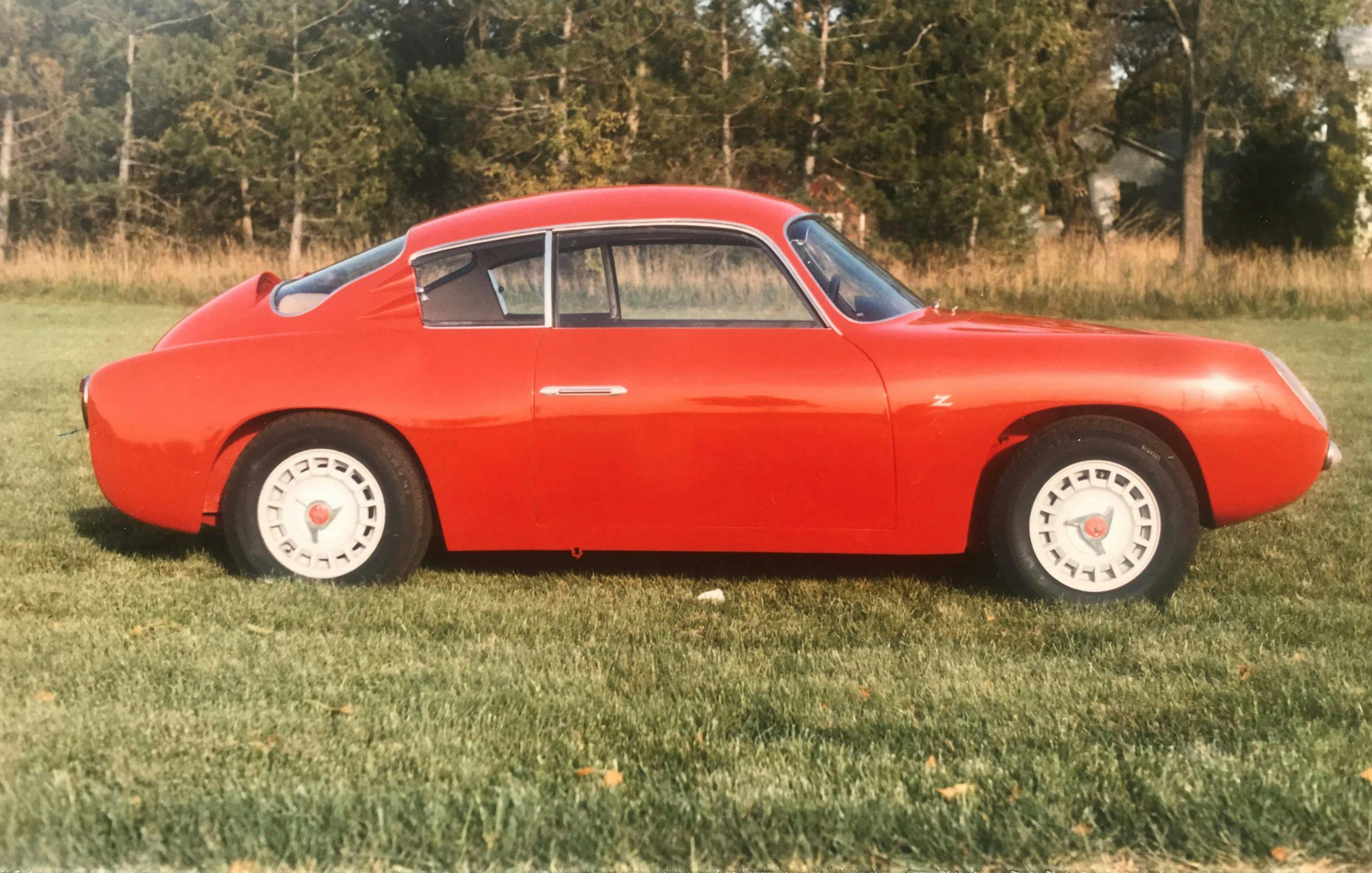

He then devoted six years to bringing a 1958 Fiat Abarth 750 Zagato double-bubble coupe back from a rusty death. Piontek relined the Italian interior with upholstery he stitched on his wife’s sewing machine. The finished product was profitably sold through an ad in Hemmings. A ’64 Jag E-Type roadster purchased with the proceeds required only a year to restore and remained in his car collection for 24 years.

The Sportech Roadster

Deciding that he preferred creating cars over restoring them, Piontek began what would become his magnum opus in 1986. Inspired by SCCA Formula Ford single-seat racers, his vision was for a street-legal two-seat roadster. Various associates at FoMoCo helped out with suspension design and body construction. He remembers the whole thing like it was yesterday, so we’ll let Piontek spin the yarn from here:

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

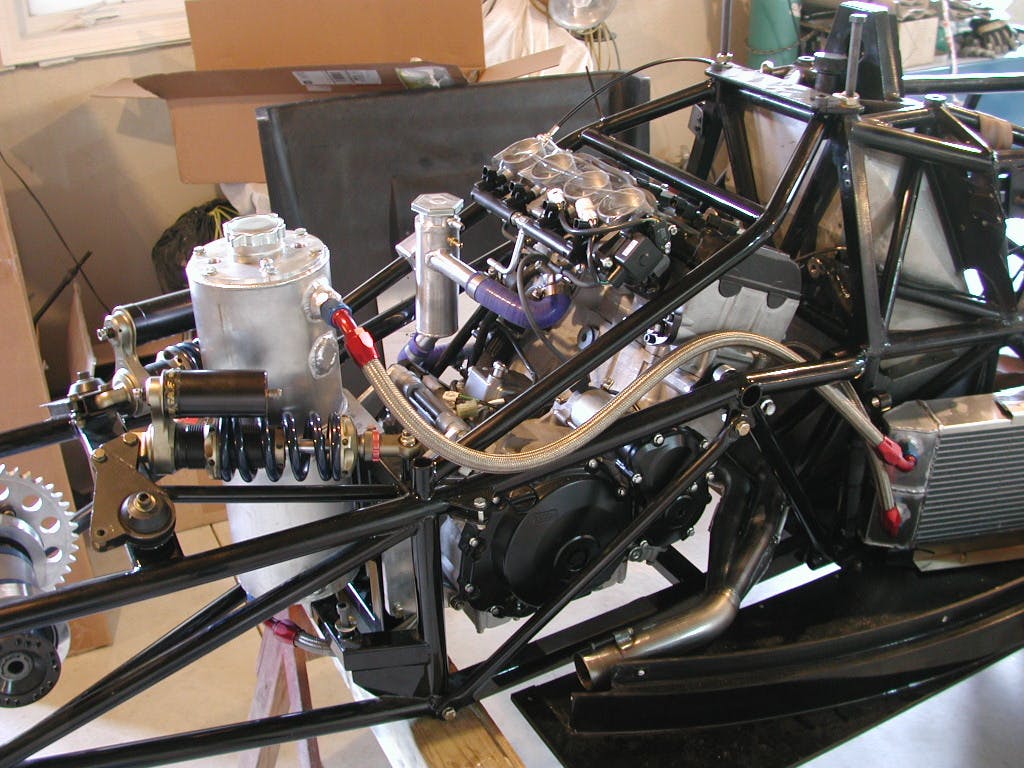

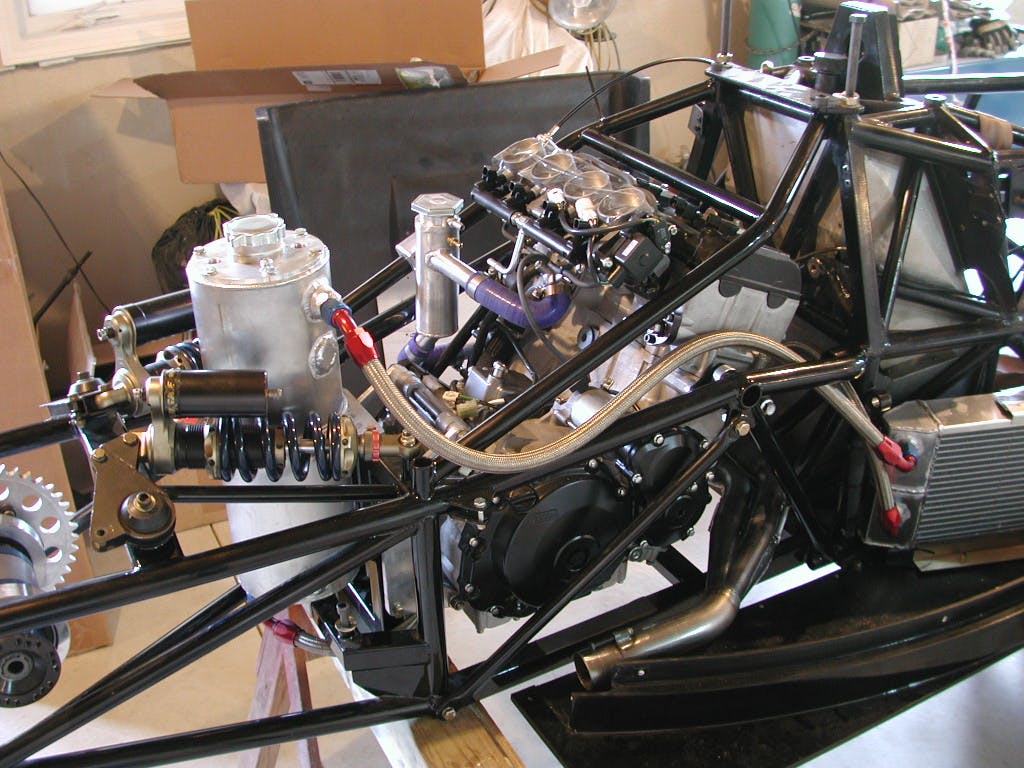

“While I lacked modern design software, I did have a large drafting table at home. So, I used a 3-foot-wide by 10-foot-long roll of paper to lay out the framework constructed using 1.25-inch square steel tubing with 0.083-inch wall thickness. A friend at work contributed the differential from a Hewland transaxle which I fitted with ball bearings and inboard-mounted brake discs.

“Since this concoction would be powered by a Suzuki GSX-R 1324cc motorcycle engine and transmission, I incorporated an electric motor for reverse. My parts list also included a shortened Toyota Corolla rack-and-pinion steering gear, Koni adjustable coil-over dampers, JFZ brakes, a Suzuki hydraulic clutch, and custom-made tubular suspension control arms.

“Particle board atop sawhorses served as my surface plate during frame construction. I used MIG welding for the frame and TIG to construct the control arms. Uprights were fabricated from sheet steel and heavy gauge tubing. Driveline bearings and half-shafts came from a VW Rabbit. I made a sequential shifter out of a simple lever operating a heavy-duty cable. Goodrich Comp T/A radial tires size 205/50R-15 in front and 225/50R-15 in back ride on 6.5 x 15-inch MSW aluminum wheels.

“Following a year of effort, I took my car to a local drag strip to shake down the finished chassis and running gear. It clocked 112 mph for the quarter-mile in 12.8 seconds. First gear was worth 50 mph!

“At this juncture, I was employed at Ford’s Design Center working on advanced concepts. We did everything from plastic body panels to 48-volt electrical systems to finished show cars. This is where I learned the design process from start to finish, including clay model construction.

“To build a body at home for what would become my Sport-Tech, (later Sportech) Roadster, I used a wooden ‘bridge’ and borrowed measuring uprights from an SCCA racing body builder. The armature was foam over wood with outer surfaces 1-2-inches below what would become the finished form. Some 2000 pounds of used but serviceable Chavant modeling clay was diverted from work to my garage for this effort.

“Ford designers Mark McChesney and Greg Miller produced a one-quarter-scale model that I measured using my Bridgeport milling machine to obtain accurate full-size section dimensions. A large turkey broiler warmed the clay to make it pliable.

“After three months of evening and weekend effort, I had a clay model to show Mark and Greg. They’d critique it for 15-20 minutes, then I’d carve the clay for 10-15 hours to implement their corrections. Once they were happy, I hired a professional clay modeler to add or remove 1/16-inch of clay here and there, including the windshield area, to achieve the final shape. Other pros made the mold and first Kevlar-reinforced body which mounted to my framework at multiple points. In addition to rocker panel attachment points, there were tubes and brackets bonded to the body and welded to my frame.

“Designing the engine cover hinge and latch arrangements consumed six months. Ducts providing air to the engine and radiator and wheel-well liners took additional time. The head and tail lamp covers are molded of acrylic plastic heated and draped over plaster molds. I used my wife’s oven for this … obviously when she wasn’t at home. The windshield was also made of acrylic. A vendor helped avoid distortion in that component.

“Greg Miller was very helpful designing the interior trim panels and bucket seats. A friend at work employed in the trim shop stitched my vinyl seat covers at home.

“Since I had already painted a dozen cars, I did the final prep work and sprayed the Sportech at home. My son, who was 12 at the time, designed the nose badge on his Mac Plus computer.

“Following two years of effort, I began driving my Sportech to work. After catching wind of this project, Ford’s Design Vice President Jack Telnack invited me to display the car next to some of the company’s clay models and show cars. Asked how much had been spent on the project, I replied, ‘about $15,000.’

“When my manager and supervisor heard that figure they were highly annoyed, given the fact our concepts cost millions to create and were at best drivable only at low speeds. Ultimately, 300 people from various supply firms viewed the car on Ford’s turntable. Unfortunately, my Ford career took a turn for the worse because of my bosses’ embarrassment.

“Shortly thereafter, Ford’s Engineering VP Neil Ressler asked me to drive the Sportech to his building. Following a 30-minute test, he noted that race driver Jackie Stewart would be in town the following week to critique some pre-production Fords. Asked if I’d be interested in Jackie’s evaluation, responded ‘Hell yes.!’

“When that day came, I had an instrument called G-Analyst installed onboard the Sportech. In every corner, Stewart reached and held 0.99 g of lateral force. Later, racing instructor Skip Barber drove my car at Lime Rock and Jay Leno tried it in California.

“Other kudos include a two-page story in Car and Driver wherein my 1234-pound car accelerated to 100 mph in 10.6-seconds, half-a-second quicker than a Lingenfelter Corvette tested in the same issue. It also earned the Design and Originality Award at Detroit’s 1989 Autorama.”

Electric Acorn: Sportech as inspiration

Alan Cocconi of AC Propulsion, the company that helped create GM’s EV1 low-volume production electric car, was intrigued by Piontek’s Sportech. The ultra-light weight, compact size, and gorgeous bodywork were perfect for a BEV in the planning stages on the west coast.

Piontek converted one Sportech to BEV operation using a 200-hp AC motor, Honda transaxle, and 28 lead-acid batteries. Renamed ‘Tzero’ this car made its debut at the 1997 Los Angeles Auto Show. Six years later, Elon Musk joined the AC Propulsion team. Impressed by the possibilities following a test drive, he raised $7.5-million of start-up capital resulting in the 2008 launch of the Tesla Roadster, using Lotus Elise chassis and body components. [For a full account of how Tesla’s towering electric oak tree grew from this little-known acorn, click here.]

Geo-based “Fun Car”

Meanwhile back at the Ford ranch, Piontek cashed out his Dearborn chips to become the American Sunroof Company’s R&D supervisor. He earned five patents in five years at that job.

Next, he moved to Ticom—a composite-plastics supplier to General Motors originally owned by Northrop Grumman. While working as a plant manager, Piontek pitched the idea of building a concept car for presentation at trade shows aimed at expanding Ticom’s business. Here’s how it came together, as told by the man himself:

“What I had in mind was a modern Jeep-like Mini Moke. We selected a Chevy Metro chassis as the substructure in hopes of re-bodying the car with a rudimentary composite body to be called ‘Fun Car.’

“I found a low-mileage wreck and had it hauled to my garage where I stripped off the sheet metal above the rockers and shock towers. To elevate the driver’s vantage, the instrument panel, steering column, and seats were raised four inches.

“My ex-Ford colleague Mark McChesney supplied a rendering of the finished product, which was handed off to Special Projects, a Detroit area show car builder. Roy Bonnett, a structural composites expert hired by Ticom, outlined the process by which the Fun Car could be manufactured using equipment already in service at Ticom. Foam cores wrapped in fiberglass would be molded in a large press. Powertrain and suspension parts would be supported by steel inserts integrated with a composite frame.

“When we presented the finished prototype at the SEMA show, lots of folks assumed it was electric. That kicked off a second edition built atop a four-door Metro floorpan powered by a Solectria AC motor and 12 lead-acid batteries. At an EV conference in Costa Rico where we showed Fun Car, the country’s president encouraged Ticom to establish a new manufacturing base capable of mass producing the car.

“Unfortunately, neither Ticom nor Northrop were interested in the considerable investment required, so only three Fun Cars were ever built. When the economy turned down, both firms said adios to the challenging automotive market.”

Necessity is the mother of invention

Luckily, Piontek landed on his feet. Jay Novak, a close associate at Ford had moved to the company’s NASCAR racing department, needed a program manager to reside in North Carolina to assist Ford teams at 26 races a year. That necessitated shutting down all garage construction operations and a full household relocation south.

Though his NASCAR assignment lasted just over three years, Piontek’s creativity never ceased. To help teams precisely set their racers’ corner weights (the vertical load carried by each wheel), he invented a tool called Scale Mat. This consists of a 4×12-foot sheet of 0.030-inch plastic that readily folds down to a 2×4-foot piece for transport. The mat shows exactly where the aluminum plates under the weighing scales must be positioned for consistent measurements. This handy device reduced the time required to accurately locate the set of four scales from half-an-hour to one minute. Eighteen years after his Ford Racing stint, Piontek still sells 30 to 40 Scale Mats per year.

Harley-powered TwinTech

Before returning from North Carolina to Michigan, Piontek hatched his next homegrown car project: a two-seat roadster powered by a Harley-Davidson V-twin driving the rear wheels through a VW transaxle.

“Jay Novak designed what we called the TwinTech in Michigan, and I constructed the exoskeleton frame in North Carolina,” Piontek explains. “We used 1.75 x 0.062-inch round tubing for the frame members, oval tubes for the control arms and CNC-machined billet aluminum for the front uprights. Start to finish, this project took but nine months.

“While the powertrain did require some development, the Twin Tech won another Design and Originality Award at the 2006 Detroit Autorama show.

“This was the best ride and handling car Jay and I had ever created thanks to its ultralight 1200-pound weight, stiff chassis, and rising rate suspension systems. There were hopes of building and selling 100 of them a year until the 2007 recession hit. Only one was ever made and it’s still in my garage.”

Formula for success

Upon his return to Michigan in 2005, Piontek turned his attention to elaborate rotisserie restorations. At least, that is, until his buddy Novak suggested converting Van Diemen Formula Fords competing in SCCA road racing to motorcycle power. Ultimately, eight kits were created and sold to enable car owners to handle such conversions on their own.

Phase two focused on the SCCA’s Formula 500 class where a rules change allowed use of 600cc motorcycle engines. Ten different cars were converted here with spectacular specs—125 horsepower driving an 875-pound (including the driver!) package. “One of our NovaBlade cars was clocked at 160 mph on the Daytona International road course while winning the SCCA’s National Championship,” says Piontek. “Another one of these open-wheelers converted to electric propulsion competed successfully at the Pikes Peak Hill Climb in 2012.”

Piontek’s most recent project was reengineering a Novak-designed SCCA D sports racer to accommodate a Suzuki Hayabusa motorcycle engine. The finished result was 200 horsepower and 125 lb-ft of torque from the 1340cc bike engine in a 1180-pound (including driver) package.

All told, Piontek constructed 30 or so cars in his garage. Factor in the scope and breadth of his creativity and you’ve got a craftsman truly deserving of the “Garagefather” appellation.

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it.

It has a Corvette mid-engined CERV concept look in it. Pretty cool.

Always nice to see the names of old colleagues appear in the press, especially when they are as unbelievably talented is Dave Piontek.

I too remember the Sportech like it was yesterday. The car graced the cover of Kit Car magazine and as a recent college grad, I loved its sport bike power plant and low cost to entry….

IIRC, another party got involved on the marketing side and shifted the Sportech significantly upmarket; dashing my hopes of ownership. I think Road and Track wrote a story about the car and this gentleman. I may have even contacted Mr Piontek after this point to inquire about purchasing one used.

In any case, if you ever decide to build a “continuation run” of Sportechs Mr. Piontek, I would gladly be first in line.

Fantastic story!

Great article! Didn’t know the Sportech hinges took so much time and effort!