Media | Articles

The development of Audi’s Quattro AWD was a natural evolution

Audi, like everyone else, is looking for ways to keep busy during pandemic quarantine. While some are unpacking old boxes in their garages and basements, the four-ring brand is digging through its history and presenting a new “Tech Talk” series, explaining company innovations in great detail. And since 2020 marks the 40th anniversary of the Ur-Quattro, let’s take a deep dive into the evolution of Quattro and the all-weather capability that technology lends to cars from Ingolstadt.

Large automotive companies produce multiple platforms and drivetrains for a full lineup of vehicles, yet if you have to sum up a brand, you may call Mazda the champion of rotary engines or affordable roadsters, Subaru the king of boxers, Porsche the flat-six maniac, Lamborghini the guardian of the naturally-aspirated V-12, McLaren the proponent of carbon tubs, Dodge the protector of the muscle car, and so on.

Audi makes a few front-wheel-drive cars mostly originating from a Volkswagen design, but its most capable vehicles have always been those with Quattro. The idea came from the mind of Ferdinand Piëch, who was inspired by the 1978 Volkswagen Iltis, a four-wheel drive military vehicle continuing where the all-wheel drive Volkswagen Beetles of WWII left off. Audi had a great five-cylinder that, once turbocharged, could compete with the six-cylinders used by the competition, and while the longitudinal engine extending way ahead of the front axle resulted in understeer, it left plenty of room at the back for an all-wheel-drive system that was superior to previous experimental and off-road designs.

The 1980 Ur-Quattro was quickly dialed up to short-wheelbase madness specification for Group B, and Audi never looked back.

Here’s how Audi explains the workings of its first system:

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

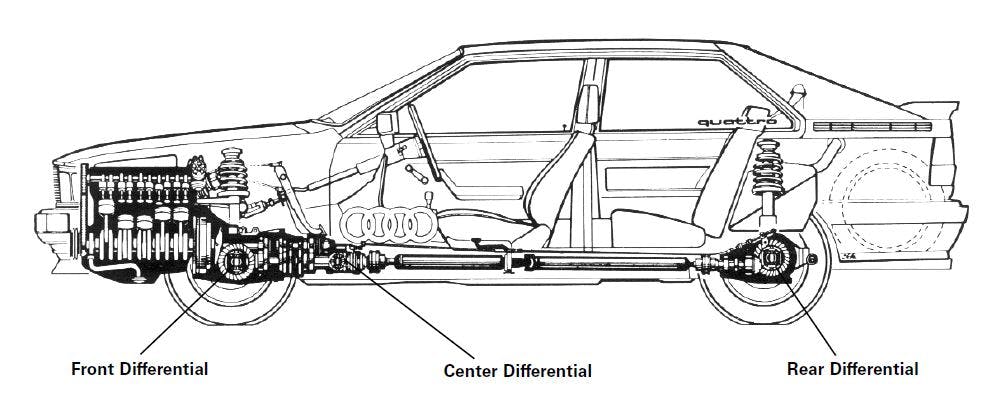

“The first quattro all-wheel-drive system used three mechanical differentials to distribute torque between the front and rear wheels. Via a vacuum-operated switch, the driver could select to lock the center differential to lock the front and rear differentials together, causing them to turn at the same speed without slip.

Ordinarily, the differential—a set of gears driving the wheels at each axle—are fully open to help compensate for the difference in speed each wheel travels. Think of taking a corner, for instance: the inside wheel will rotate far less than the outside wheel. Locking the rear differential helps ensure power gets to both wheels equally, which is needed when driving on slick surfaces or traction-limited situations but also to maximize grip in any condition. The front does not have a locking differential because of the need to turn.

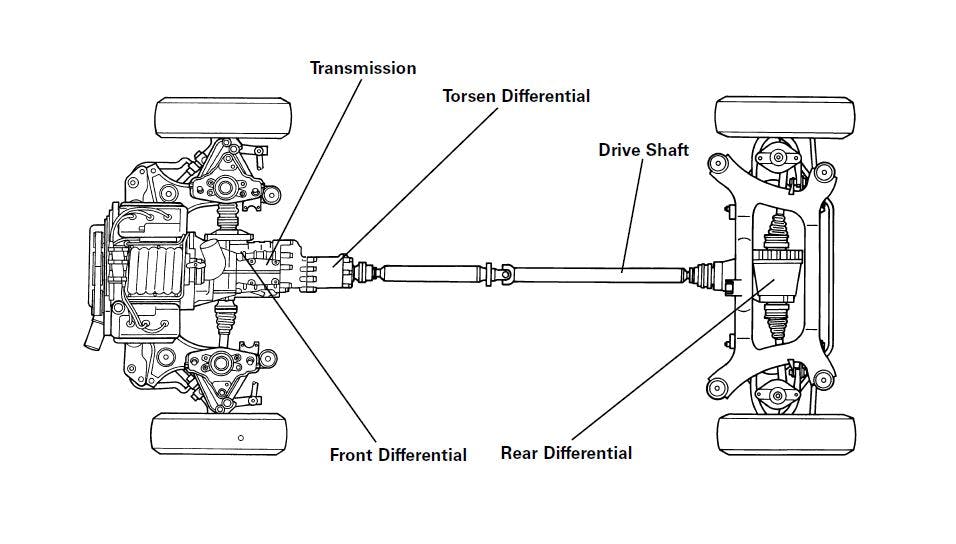

In the first major update of quattro in the late-1980s, a Torsen (short for torque-sensing) differential that automatically split power 50:50 from front to rear replaced the original manually operated center differential. A rear differential lock switch remained; some larger vehicles were available with a rear Torsen differential as well.

The Torsen center differential housed a pair of helical planetary gears. The gears were held in tight-fitting pockets inside the housing and splined together through spur gears at their ends. These spur gears did not allow the planetary gears to rotate in the same direction. However, when an axle would lose traction, the spur gears would help channel torque to the wheels with traction. This could allow up to two-thirds of the vehicle’s torque to be sent to either the front or rear axle.”

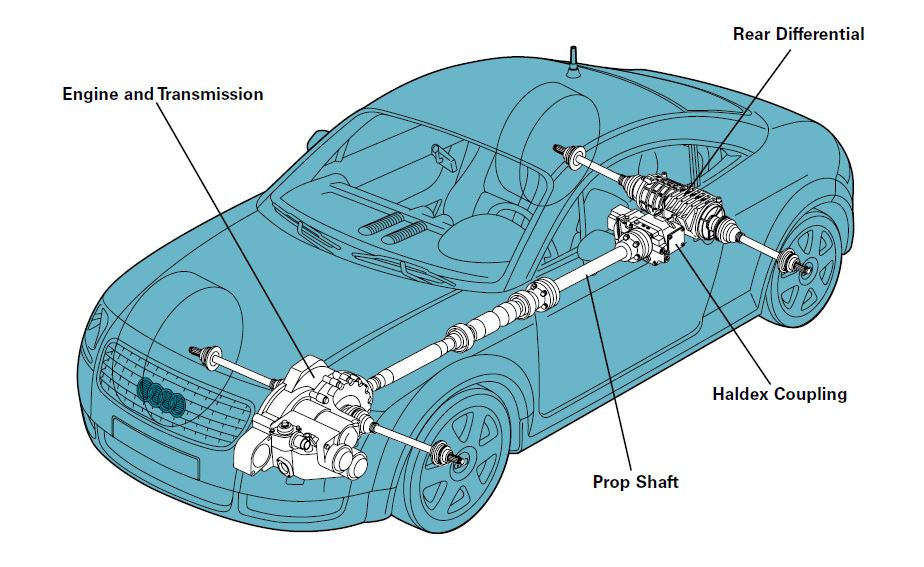

After this came the transverse engine period, requiring Audi to move on to something very similar to what Volkswagen has been using for its synchros: a Haldex coupling system. Starting with the 2000 model year TT Quattro, you got the same tech as in an all-wheel-drive Golf. More from Audi’s description:

“In a Haldex application, a propshaft runs from the transmission to the rear differential. The end of the propshaft connects to the input shaft of the Haldex coupling. The end that connects from the Haldex coupling to the differential is called the output shaft.

On a slippery driving surface, one or more wheels may have reduced traction. As a result, the Haldex coupling senses a difference in speed between the input and output shafts and takes action. Inside the unit, a roller bearing begins to rotate around a lifting plate with an undulating surface. This results in a lifting motion of a piston, which builds up hydraulic pressure. This pressure is applied to the Haldex clutch that connects the front and rear axles, making all-wheel drive possible. Sensors reading engine speed, accelerator pedal position and engine torque also participate in the activation of the rear differential. In addition, Electronic Differential Lock (EDL) utilizes the ABS system to control loss of traction at each individual wheel.”

As you’d imagine, a system using a Haldex coupling isn’t as strong as a mechanical Torsen. In fact, I remember when the Focus RS came out, Ford explained that it went for the same more complex GKN system that the Land Rover Evoque was using because Ford’s early Haldex prototype simply couldn’t take the power of the 2.3-liter turbo-four.

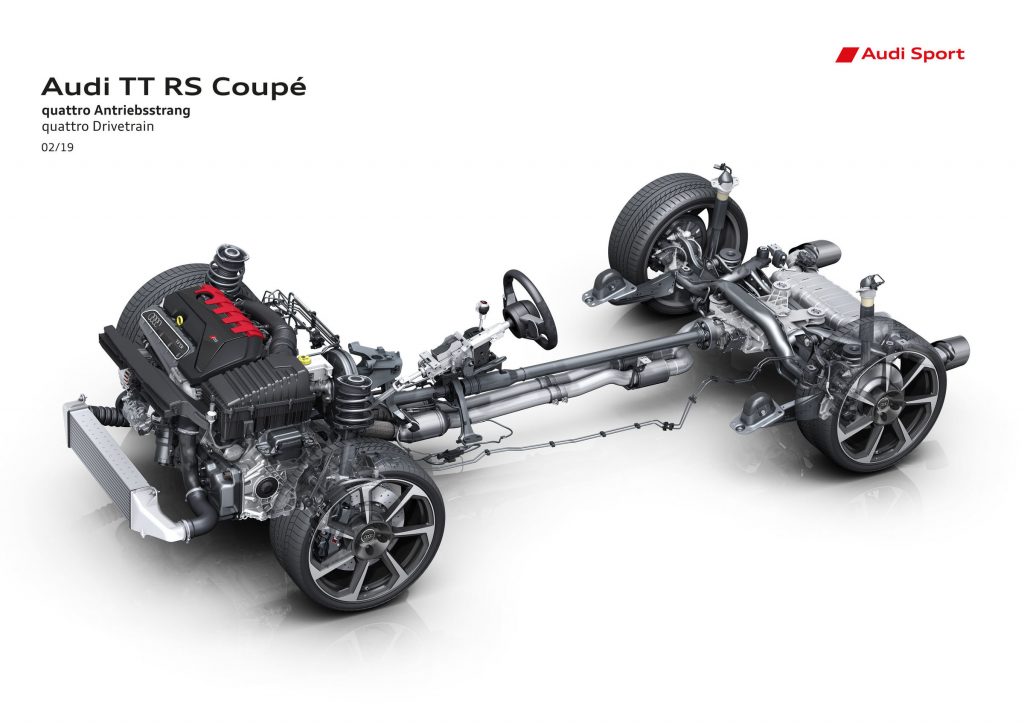

That is why, for the excellent and highly capable TT RS, Audi beefed up its multi-plate clutch Haldex with a constant velocity joint before the cardan propeller shaft, and a compact rear-axle differential. Drive a 2020 TT RS, and you shall be convinced.

As the number of microchips, batteries and customer demands grew, so did Audi’s Quattro offerings. Currently, the company is using a whopping five different all-wheel-drive solutions:

- quattro all-wheel drive for medium and large vehicles using the MLB evo architecture (8-speed Tiptronic (torque-converter automatic transmission) and 7-speed S tronic (dual-clutch automatic transmission)

- quattro all-wheel drive with ultra technology (7-speed S tronic) using the MLB evo architecture

- quattro all-wheel drive for transverse applications using the MQB architecture

- quattro all-wheel drive for the Audi R8 using the MSB architecture

- e-tron electric quattro all-wheel drive, using electric motors on each axle

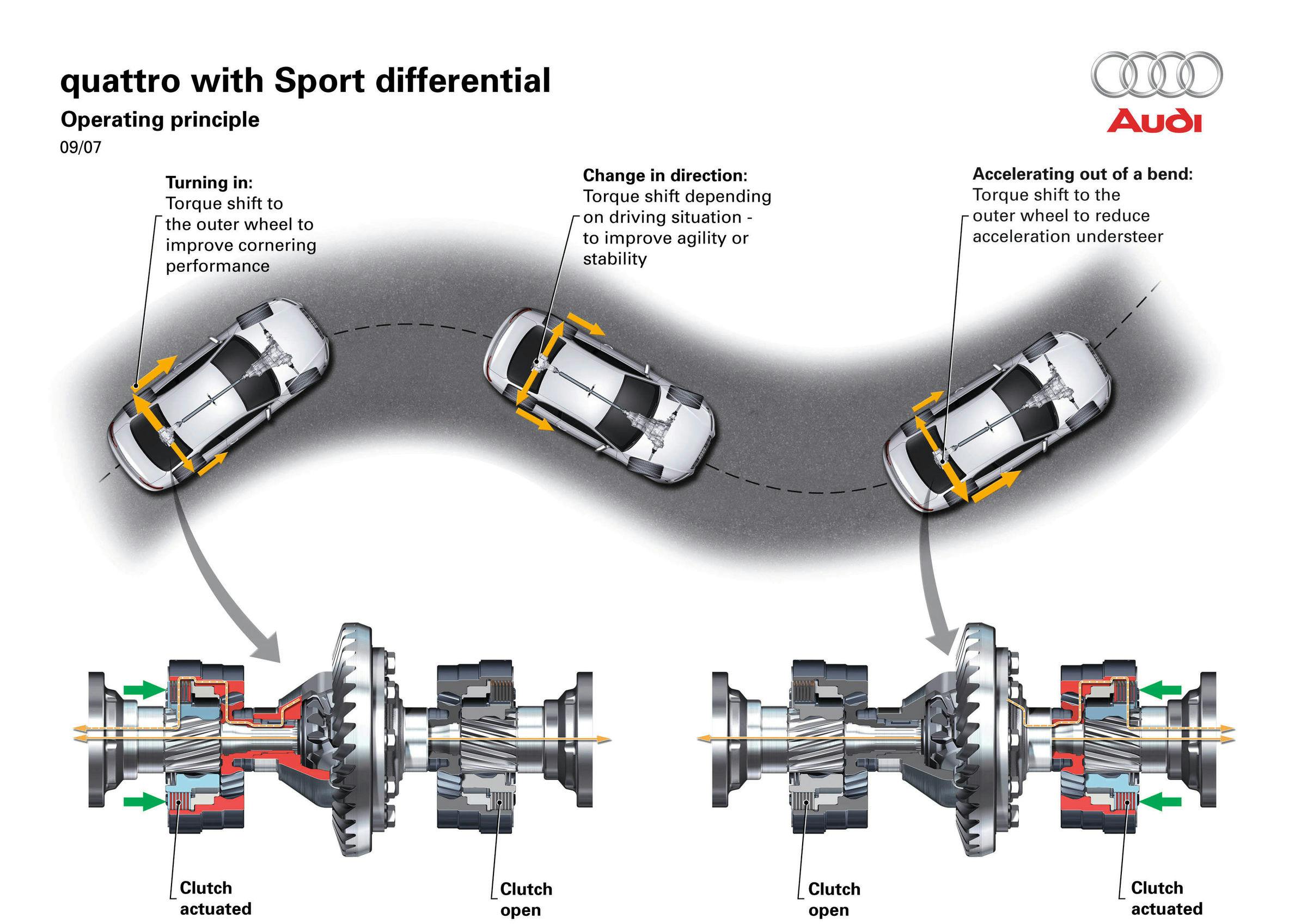

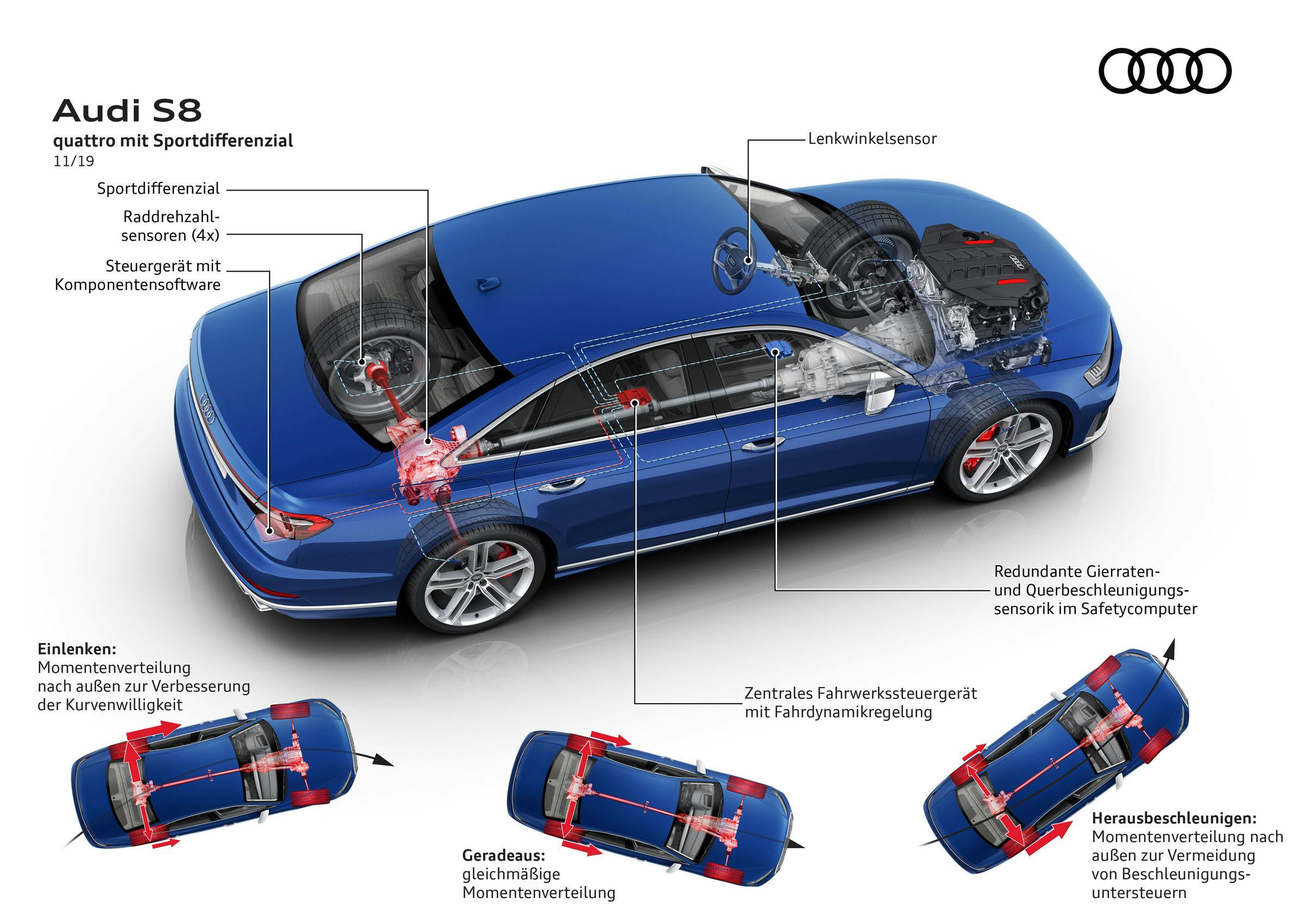

“Default power distribution is 40:60 front to rear, with up to 70% of power to the front wheels or up to 85% of a vehicle’s power to the rear. Additionally, electronic wheel-selective torque control can assist traction across each axle through individual wheel braking. Torque control is provided by an intelligent software function of the stability control.

In S and RS models, the rear Sport differential has the ability to overdrive the inside or outside wheel, or even send almost all power from one rear wheel to the other, in hard cornering, creating more neutral handling. This is known as torque vectoring.”

Indeed.

When it comes to fully electric Audis, there are even more options. A pair of electric motors with single-speed gearboxes can divide torque flexibly without using a differential, as the computers figure out how to put all that power to the ground. Yet before we would say goodbye to that mechanical lockup feeling for good, let’s investigate Audi’s Lamborghini-sibling flagship, the V-10 R8.

While the first V-8 and V-10 R8s used viscous coupling, the second generation packs an electro-hydraulic multi-clutch pack in the front, making it capable of transferring 100 percent of its torque to the front wheels, instead of just 30 percent like before. Both of its axles are also capable of torque vectoring. That’s neat, yet all this tech kind of goes to waste if you consider the rear-drive 2020 R8 RWD to be a superior (or at least more entertaining) driving machine. Most do, which tells us that while the Quattro turns the TT RS into a mad rally car, the same idea makes the R8, for some, less of a supercar. Still, on a greasy day, you’ll be grateful for Quattro—as fast Audis since 1980 have proven.