Media | Articles

Can you improve a factory cylinder head with 20 minutes of work?

An engine is an air pump. Make that pump more efficient, and you will make more power. More power equals more fun. I like fun, and that’s why I took a carbide burr to one of the hardest-to-find (let alone repair) parts of my Honda XR250R.

A lot of folks blather on and on about the indestructibility of Honda’s XR-series motorcycles. Based on my experience, most of those people are operating on the assumption that ignorance is bliss. While this platform is very durable, it has flaws. The steel frame and simple suspension may be nearly bulletproof, but the engine still needs the care and attention that all engines need. Fresh oil, valve adjustments, basic mechanical sympathy.

I know that many owners don’t maintain these bikes as they should. I’ve seen the evidence, if only because I have a knack for purchasing the neglected examples—the ones that were allowed to run low on oil, which destroys the cam center journal, or whose valves got so far out of adjustment that one broke, and I’m left playing the motorcycle version of CLUE. Valve stabbed head in the combustion chamber.

It’s a game with no winners.

If it sounds like I’m ranting, I am. Due to a widespread tolerance for deferred maintenance, I must hoard good cylinder heads to make sure my bikes can stay running. For a few months last year, I bought every parts bike within a two-hour drive that possessed a good cylinder head—along with any comparable examples that appeared on eBay. That totaled four.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Now, I have my pick of the lot for the latest engine I’m assembling. The one I chose? The one with the most damage. Let me explain.

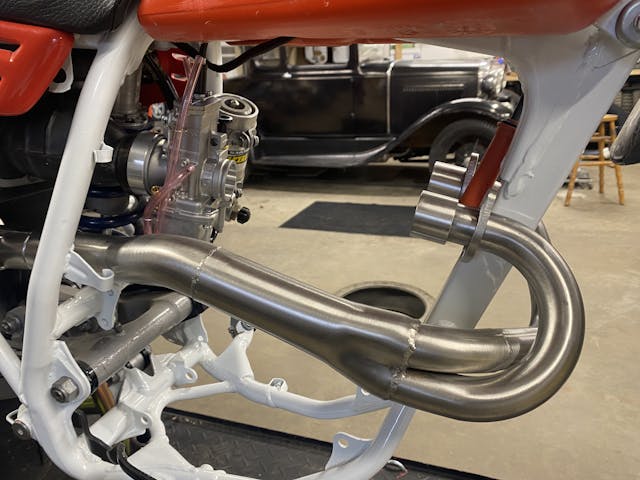

This engine is going into a motard race bike, which has been a back-burner project ever since I did some road racing during the Six Ways to Sunday project last year and had a blast. Even at a short track like Blackhawk Farms, the XR250R left me wanting for power, so this time around I’m dialing the engine build up a notch. This air pump needs to get more efficient. A 2mm larger carb and big, stainless-steel header were no-brainers, but each required little more than swipe of a credit card. To get real performance, I had to break out the tools.

With most automotive applications, you can buy an aftermarket cylinder head and, by simply bolting it on, gain more airflow in and out of the combustion chamber. Heck, for some applications, buying an aftermarket head is almost cheaper than rebuilding the factory unit. No such support exists for the Honda XR series, though. If I wanted to make the intake or exhaust runners in the head flow better, it was up to me.

First, I had to admit I had no idea what I was doing.

After acknowledging my lack of experience, I took advantage of my resources and made a field trip over to the Redline Rebuild garage. You might not have access to Hagerty’s engine master Davin Rekow, but I do and will leverage that any time I can. Cylinder head in hand, I described my goal. We both examined the casting, Davin using his callused hands to evaluate how much material there was to spare.

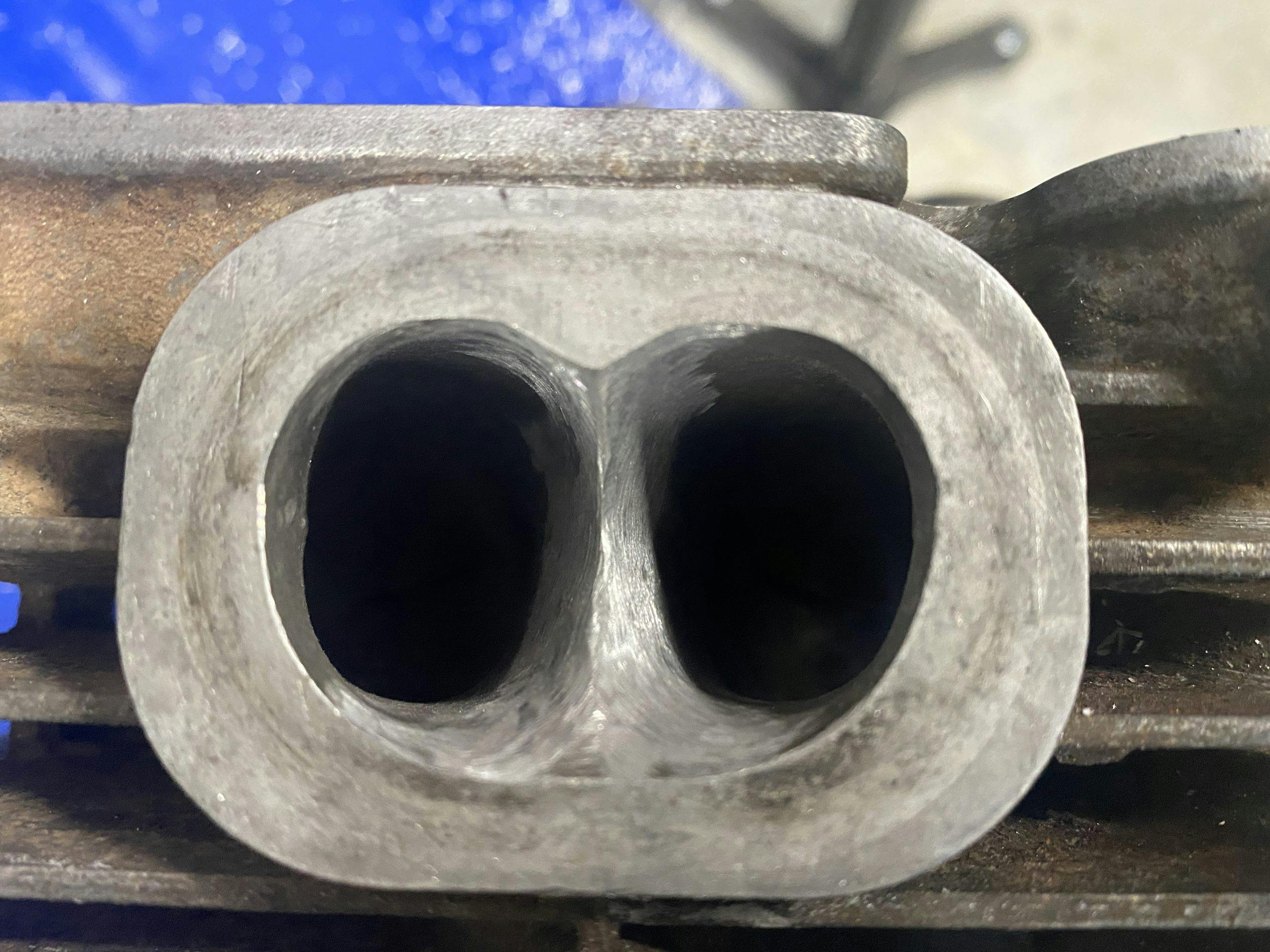

“There really isn’t much here. I would just clean up this little peak to more of a knife edge and call it good. I mean, that certainly can’t hurt.”

I grabbed the die grinder, chucked in the wide-fluted bit for aluminum and connected the air line. Then I took a deep breath and started making chips. The burr easily scooped away tiny slivers of metal. It was honestly a little addicting to watch fresh silver emerge from beneath the stained aluminum. It took all of my self control to not keep whittling away until I was left with a pile of shaving and no more cylinder head.

Davin warned me that the burr would remove material quickly, and that I really didn’t need to take out much. I shouldn’t take out much, he said, because the little divider that I was trimming and sharpening hid a passage for the cylinder head bolt. If I removed too much material, I’d have to grab the TIG welder or scrap the part all together. Less than ideal. A regulator in the air line, which helped control the speed of the die grinder, did much to prevent me from getting too aggressive.

Small cuts, then—a touch here and a scuff there. Blend my work smoothly back into the factory casting further into the intake runner. Once I was happy with the “big” cuts, and got Davin’s nod of approval, I swapped a sandpaper roll into the die grinder and smoothed things out even more.

There has been much debate over the proper texture of an intake runner. With the advent of flowbenches, the score could be settled: A semi-rough surface is best because it helps the air to tumble and mix before it hits the combustion chamber. The 80-grit sanding roll would leave the perfect finish.

In all, this project required 15 to 20 minutes of careful work. Will the changes turn my next race engine into some fire-breathing beast? Absolutely not. Davin and I agreed that they certainly couldn’t hurt, though.

Now, the head gets packed in a box and shipped to Millennium Technologies in Wisconsin to get the combustion chamber repaired and the valves serviced. It’ll come back ready to be bolted atop the fresh bottom end I’ve got on the workbench, and I’ll be in the homestretch of getting the engine race-ready in time for this fall.