Media | Articles

A charged debate: Battery maintenance tech explained

Batteries are something that most of us forget about until the moment our car won’t start or when it suddenly collapses on the side of the road. Generally, that detachment is harmless; A well-functioning and regularly used electrical system will make maintaining a battery a set-it-and-forget-it proposition. However, most vintage and classic vehicles don’t get the regular use your daily driver does.

Storage and limited use can be hard on a battery—or is it? There are plenty of myths surrounding proper battery care, so we will dive into the basic tech to help you decide the proper care and feeding regime in your particular situation.

The basics

Batteries exist as chemical storage units for energy, which can turn the starter, fire the ignition, and use various accessories (the first is typically the most important task). There are two major types of automotive batteries: wet cell and AGM.

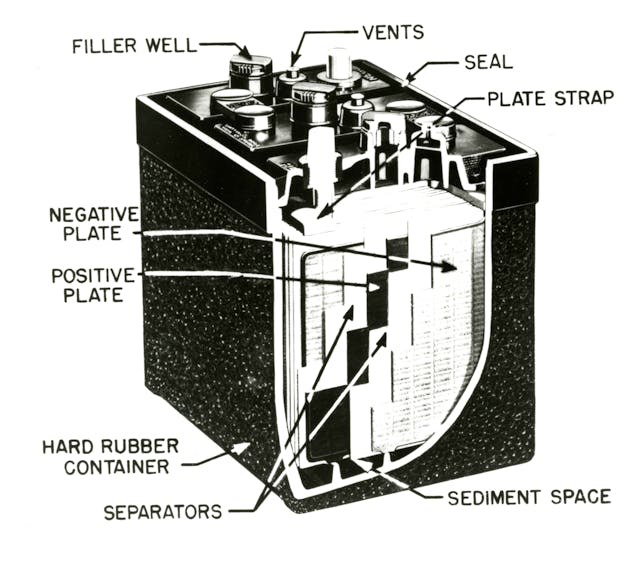

A “wet cell” is essentially the fancy name for a lead acid battery. This is the most common unit in vintage vehicles and is also the most affordable to produce. The core is comprised of two sets of lead plates which act as electrodes—half positively charged and the other negatively charged—spaced slightly apart from each other. The case holding these plates is then flooded with an electrolyte solution. Linking the electrode plates determines the voltage of the battery.

The second type of battery is an “absorbent glass mat,” or AGM battery. It is constructed similarly to the wet cell variety, but rather than leaving the electrolyte mix free to slosh around inside the battery case, an AGM uses an absorbent glass mat to separate the electrode plates and to keep the electrolyte solution contained. AGM batteries are popular because they are sealed and can thus be mounted in a wider range of positions and spaces than wet cells.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Charge and discharge

The chemical process inside a battery may seem like witchcraft, so we’ll give you a quick breakdown. Connecting a battery into a circuit creates activity within the electrolyte solution. The chemicals that compose the electrolyte react with ions in the electrode plates, which triggers the electrons’ march through the circuit attached to the terminals of the battery. This process continues until the electrolyte is consumed by the reaction. The battery is declared “dead” when the ions stop moving through the electrolyte, because this halts the flow of electrons through the larger circuit.

When charging, the ions reverse their progress through the electrolyte. Charging still depletes the electrolyte solution, and thus it is commonly accepted that keeping a battery topped off is the best way to ensure its longevity. However, your preferred charging method also involves one of the great debates in the classic car world—battery storage solutions.

Storage

This discussion often flares in the winter months, when northern states tuck vintage cars into medium-term storage while the snow and salt besiege our roadways. Some owners in desert states store for the summer months, however; the need for months-long battery storage isn’t confined to one climate.

A slow discharge naturally occurs within a battery, which, if left unchecked, can strand your car in storage just when you arrive to set it free. (Seriously, how depressing.) Overcharging is just as harmful to a battery’s life as a full discharge, but luckily a few inventions over the years have helped us enthusiasts to tackle this dilemma.

The solution most will prescribe is a trickle charger, which gives the battery a consistent small charge roughly equal to the rate of natural discharge. A trickle charger is especially handy for more modern enthusiast cars, because battery disconnection or removal can cause headaches with security systems or other onboard settings. It’s also easy to use; simply park your car, clip on the leads, and plug in the charger.

You can go a step further with a battery maintenance charger (or smart charger). These units sense the charge state of the battery and, rather than numbly applying a constant low-voltage charge, they cycle based on the battery’s needs. These chargers’ digital brains prevent overcharging, which even trickle chargers can produce. Most smart chargers are also idiot-proof and can sense whether they are hooked up improperly. We’ve all been there.

The third option for maintaining a battery is to disconnect it and set yourself an alarm for a few weeks down the road. Allow the battery to discharge naturally during that set time and then hook up a standard charger to top off the charge. This strategy requires significantly more discipline and makes it much easier to ruin a battery.

You can use any one of these charging options regardless of whether your battery is in your car or outside it. Depending on your storage situation—principally, on your access to power—you can pick the most relevant solution to ensure that, come spring (or fall), your ride can chug to life on its own battery power, no jumper box needed.

The final myth

The one that never dies: “Don’t place your battery directly on concrete; it’ll ruin it!” This is false. Modern batteries are well insulated by their plastic cases from the moisture of a concrete floor. Sure, it doesn’t hurt anything to elevate the battery, but it’s not mandatory (as it once was).

Storage is a part of most vintage car owners’ lives, and winter is right around the corner for many of us. Prepare your battery storage plan now, and you can sleep easily dreaming of quick starts and comfortable cruises. If you have any other battery tips, be sure to leave them in the Hagerty Community below.