Media | Articles

8 carburetor terms you should know

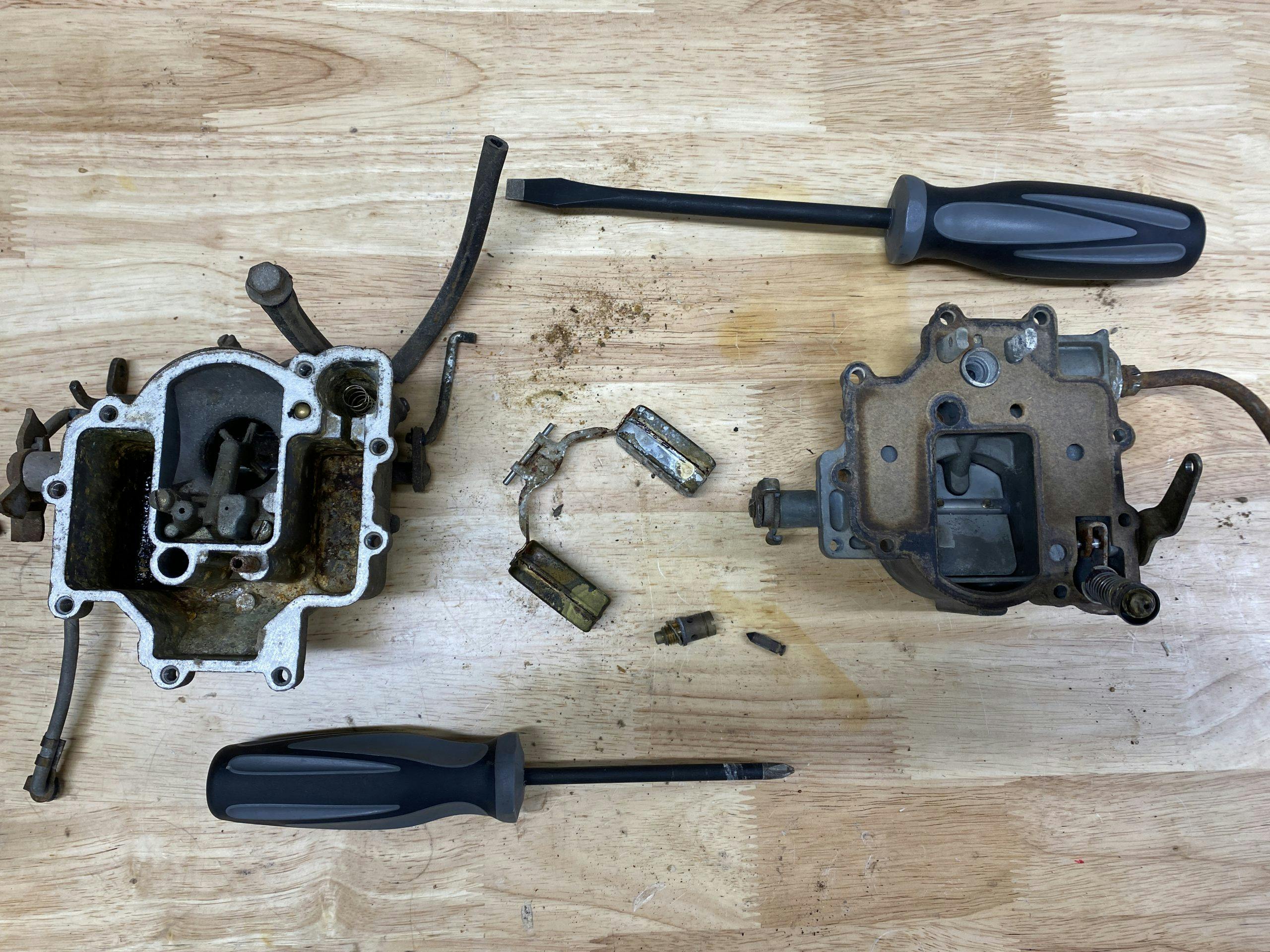

As enthusiasts of what can easily be considered outdated vehicles, there is a whole host of terminology that can leave one scratching their head as they dive into DIY projects the first time. In an effort to help shed some helpful light, here is a brief glossary of carburetor terms that will set a good baseline for terms and parts inside these antiquated atomizers.

For visual examples, I tore down a Rochester single-barrel carb that was languishing on my parts shelf. Luckily, it demonstrates the parts identification pretty well, but every car is going to be a little different.

Needle and seat

The needle (in hand) and the seat (threaded into carburetor body) that regulate the fuel flow into the float bowl. Kyle Smith

The first stop for the flow of fuel coming into a carburetor is the needle and seat. Essentially, this is a basic valve. The seat is typically conical and the needle has a point which seals against the seat to stop fuel from entering the carb at a certain level. This prevents flooding the engine and engine compartment.

Float bowl

This is the float bowl. This picture also shows how the carburetor can fill with debris and residue, leading to problems. Kyle Smith

Think of this as a second, very tiny, gas tank. The fuel is pumped (by gravity or a positive displacement pump) from the vehicle’s fuel tank to the carburetor, where a small amount of fuel is stored in the float bowl before it is pulled into the airflow entering the engine. The amount of fuel in the float bowl keeps the engine from ever starving for fuel and acts as a cushion for times where a sudden large draw of fuel might be needed and the fuel pump would not be able to instantaneously supply that fuel.

Float

Brass floats are commonly found in vintage carburetors. Kyle Smith

The needle and seat have to be controlled by something, and that something is a basic float. Typically floats were brass, but on older cars can be cork, and in recent years rebuilds kits could include plastic floats. Regardless of the material, it is the air inside that makes them work. The float is attached to a lever, with the needle and seat situated on one end. When the fuel level raises the float high enough, the needle and seat are forced to close.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

How high the float needs to rise before closing the needle and seat is the float height. Too low and the engine might starve for fuel on acceleration, too high and the car might occasionally flood or sputter from too much fuel forcing its way into the engine.

Jet

Here is an example of two different jet sizes side by side. The center hole is precision sized to provide a specific amount of fuel flow. Kyle Smith

The fuel flows in thought the needle and seat, hangs out in the float bowl for a bit, and then goes through the jet before entering the engine. At its most basic, a jet is a precision hole. The size of the hole determines how much fuel enters the engine. Too large, and the spark plugs will foul when they fail to ignite the very rich mixture. Too lean and the mixture could ignite from being compressed rather than the spark plug, which can cause a lot of damage.

If atmospheric conditions change, or if engine parts are changed or upgraded, the size of the jet may need to be adjusted. Jets are often threaded into place and are available in different sizes relatively cheaply, don’t try and drill out the jet to a larger size, as jets are sized more precisely than your drill bits.

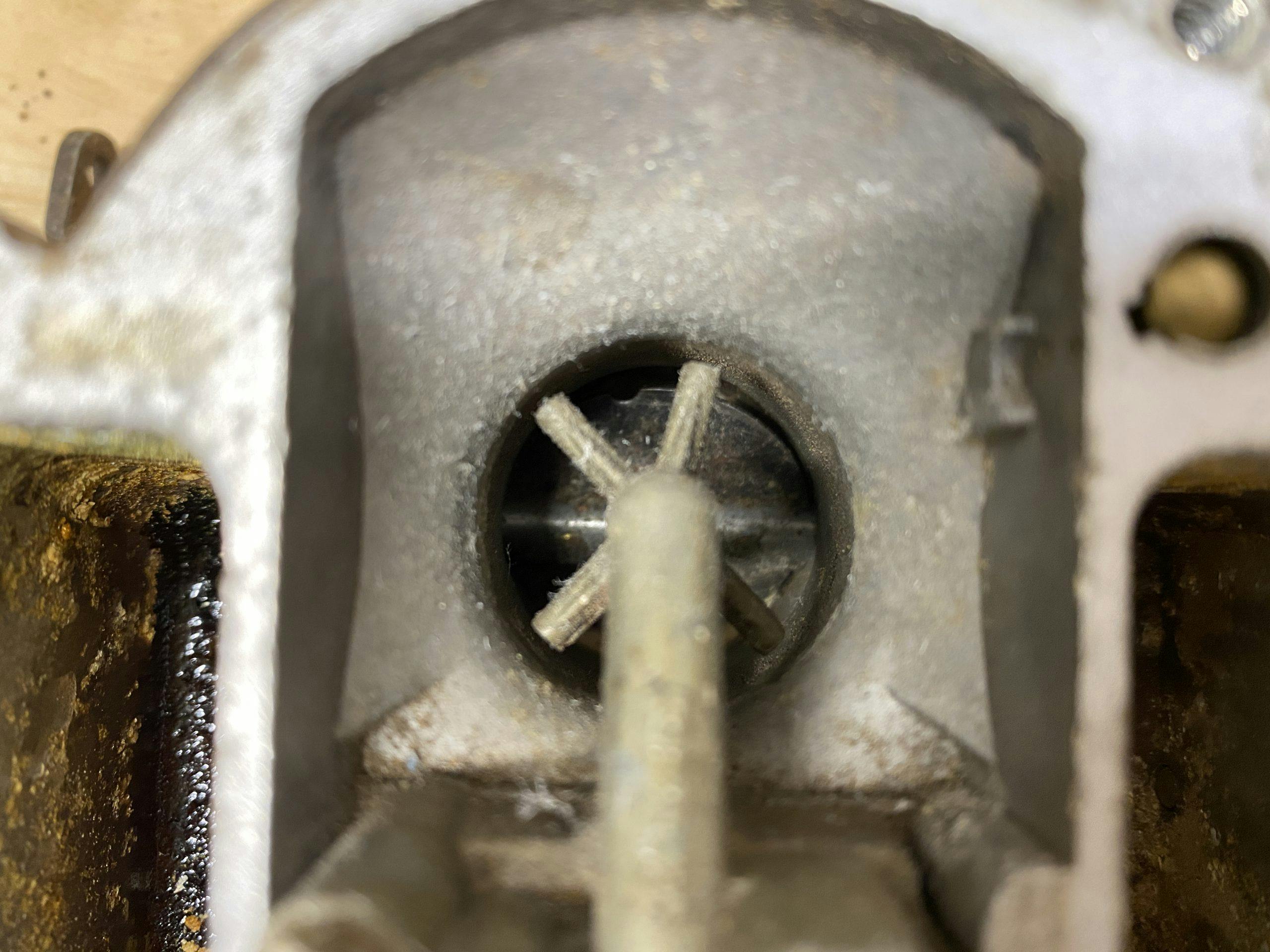

Venturi

You can see how the throat of the carb narrows, which creates the drop in pressure that pulls the fuel into the engine. Kyle Smith

This is the word for the bottleneck in the throat of the carb that makes it all work. It is the Bernoulli Principle at play as the airflow is slightly restricted by narrowing the opening and then opening it back up again. That bottleneck speeds up airflow, which then creates a drop in pressure. That pressure drop is what pulls the raw fuel through the jet and into the airstream as it enters the engine.

Accelerator pump

This is the accelerator pump. The rubber cup at the bottom forces additional fuel into the engine when the accelerator is operated quickly. Kyle Smith

As engines progressed, the demand for fuel when quickly accelerating could not be immediately met by the fuel being pulled in by the venturi. The operator would press on the accelerator and the engine would initially bog due to the lack of vacuum before responding by pulling in the additional air and fuel the operator wanted to add.

The accelerator pump is a simple solution to that problem. A linkage attached to the accelerator engages when the operator makes quick changes to the throttle. This linkage would use a small pump to force a small amount of raw fuel into the airflow. This fuel prevents the bog of quick accelerations.

Throttle blade

The throttle plate in the closed position. Kyle Smith

The throttle blade is a simple valve that controls the airflow into the engine. At idle, the throttle blade allows a very small amount of air into the engine, and at full throttle, the throttle blade is parallel with the throttle bore to allow as much airflow as possible.

Choke

Here is the choke plate in the closed position, where it serves to restrict air from entering the engine, causing a richer air/fuel mixture. Kyle Smith

Modern fuel-injected engines have spoiled drivers so much that even an automatic choke requires a reminder of how to operate it. The choke is similar to the throttle blade, but it sits above the venturi rather than below it as the throttle does. It creates a restriction so taht as the engine cranks on startup there is less air in the air/fuel mixture.

That richer mixture ignites easier, giving the engine better starting manners when cold. Automatic chokes are often set by pressing the accelerator once before starting the engine, and as the throttle is used while driving the car it automatically disengages. Manual chokes require the driver to remember to disengage the choke as the engine warms up.

Hopefully this quick list clears up some of the terms you might have heard in conversation, or maybe gives you a better understanding of the complicated processes that are happening under the hood. Is there a term or process with vintage cars you find especially confusing? Leave a comment in the Hagerty Community below and we’ll see if we can clear it up for you.