Media | Articles

16 cylinders and 270 mph, in 1938: The Auto Union V-16 was an audacious engineering feat

Here at Hagerty, we are reminded that the word driving has meant since pioneer days the controlling of the movement and direction of a powered thing. Nature’s four hooves eventually gave way to man’s own engines as the power source, and the latter became the canvas for mechanical geniuses such as Ferdinand Porsche. Well before putting his name on his own automobiles, Porsche was prone to the kind of audacious engineering that produced feats worth remembering and celebrating today, such as the Auto Union V-16.

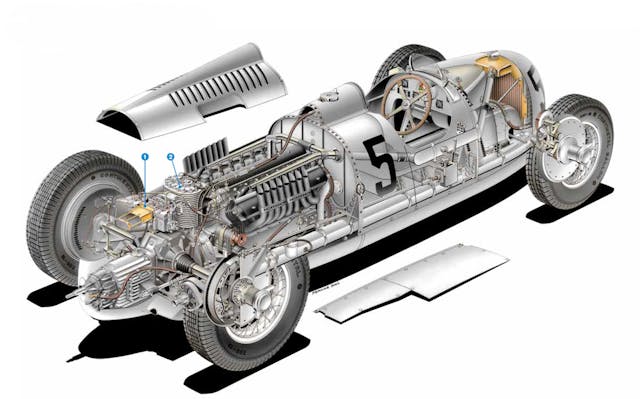

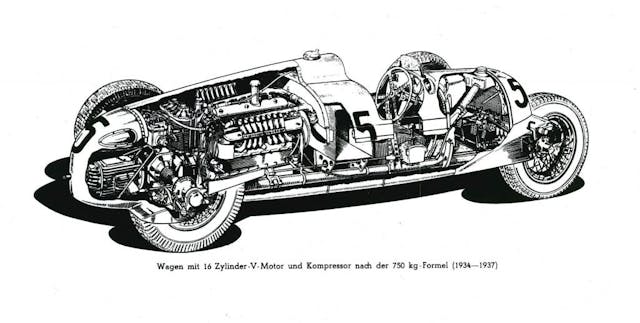

Grand Prix competition was turned topsy in 1933 when the sport’s organizers broomed antiquated “monster” single-seaters in favor of much lighter racing sculls. The 900-kilogram (1984-pound) minimum weight became a new 750-kilogram (1653-pound) maximum weight exclusive of tires, fluids, and the driver.

Anticipating an opportunity for the Fatherland to shine on the world motorsports stage, German chancellor Adolf Hitler chipped in 500,000 Reichsmarks of government sponsorship, or about $2.4 million today, toward the further development of his Silver Arrow racing cars. Imagine the chagrin at Mercedes-Benz when upstart Auto Union, the new firm formed by the merging of Audi, DKW, Horch, and Wanderer, raised its hand for a slice of the backing, intending to field a brilliant race car designed by Ferdinand Porsche.

Though he never completed any formal engineering training, Porsche’s résumé was already long before he set upon the task. He had built the first hybrid-electric car, in 1901, fitted superchargers to Mercedes-Benz SSK race cars in the 1920s, and drew the first sketch of the original VW Beetle on the back of an envelope. He was also a brilliant organizer, harnessing the talents of those working in his engineering consultancy such as chassis specialist Karl Rabe and Josef Kales, an aircraft-engine designer whom Porsche put to work on the Auto Union.

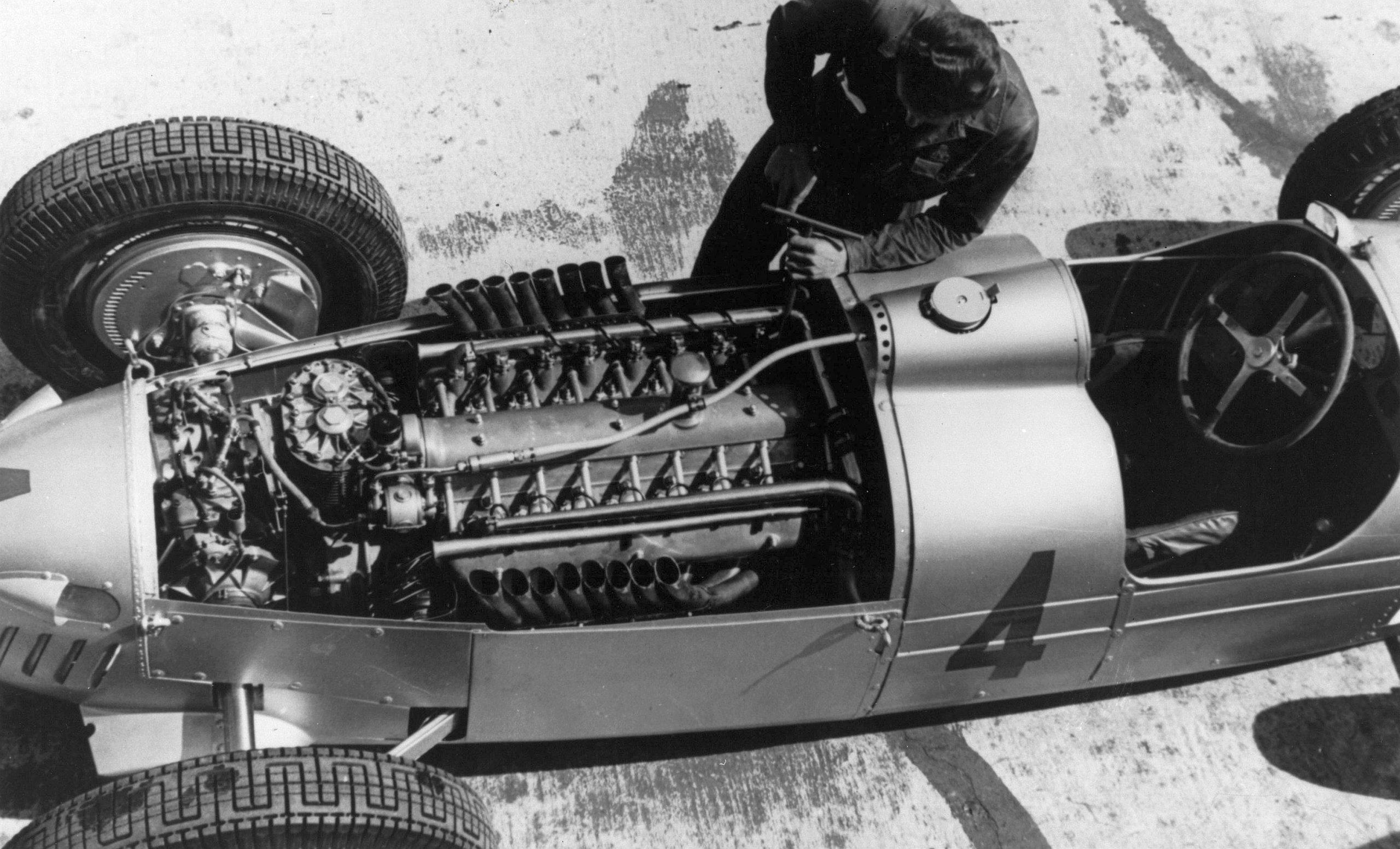

The jewel at the center of Porsche’s mid-engine P-Wagen was racing’s first V-16 engine. Although Cadillac, Marmon, and Peerless powered their early-1930s flagships with V-16s, the engine configuration was untested in motorsports. Instead, Alfa Romeo, Bugatti, Maserati, and Mercedes-Benz preferred supercharged inline-eights. Auto Union’s gambit was to double the number of cylinders in order to cram more displacement under the new 750-kilogram weight limit. Instead of chasing horsepower with a soprano redline, Porsche sought tire-melting torque for the Auto Union delivered at a lower, more basso profundo rpm.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Why exactly Kales picked 16 cylinders isn’t known, though it was likely to maximize engine torque by the use of low-stressed reciprocating parts offering the largest possible displacement. Torque is directly proportional to displacement, and if the pistons and rods don’t have to rev to the sky, they can be leaner and live longer. Rather than use fewer but larger cylinders, as were some of Auto Union’s competitors, more cylinders with smaller bores kept the engine’s length reasonable. Notes Porsche historian Karl Ludvigsen, in this period, Bugatti had tried to build a 4.9-liter straight-eight that was heavy, unbalanced, and unsuccessful, while Alfa Romeo had experimented with a twin-crankshaft 4.9-liter U-16 that broke many a track record (and a lot of engine components). With such ideas and inspiration flying around, a V-16 was almost bound to come along.

The only real drawback to extra cylinders was some increase in friction plus the extra cost of making them, though that was obviously not a racing issue. Yes, this V-16 was intentionally contrary to conventional high-rpm motorsports thinking. But don’t forget that the whole car could not top 750 kilograms. A major benefit of the novel mid-engine layout was the integration of the engine, transmission, and differential components, thereby saving the weight of a driveshaft.

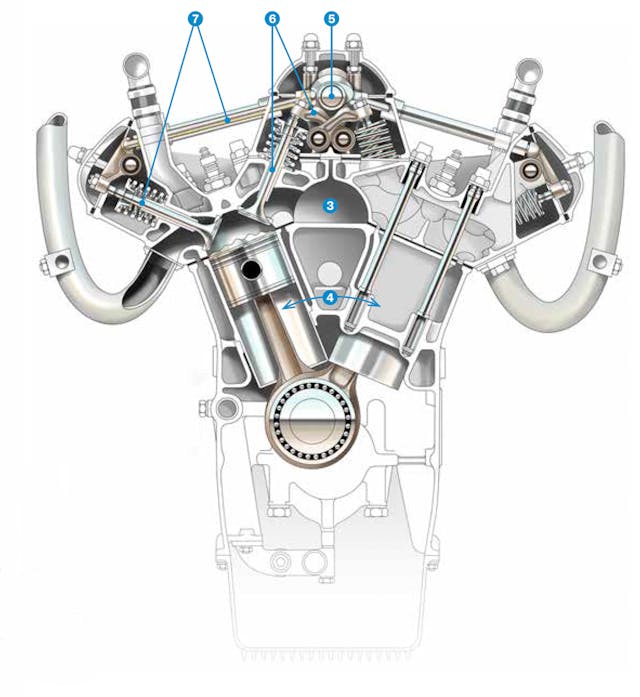

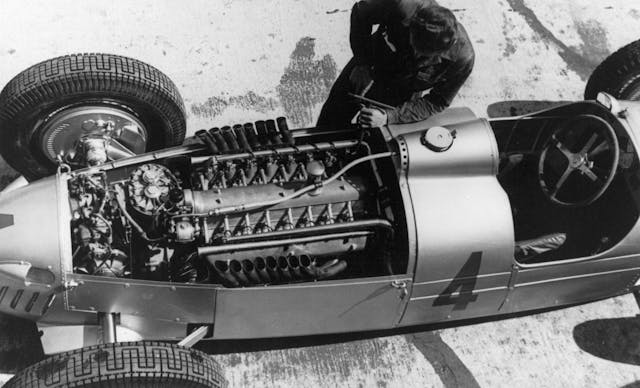

Indeed, everything about the Auto Union V-16 was revolutionary. A 45-degree V-angle provided even firing intervals and narrow width. Common practice in the 1930s to forestall sealing issues was an integrated head-and-block assembly made of welded iron and steel bolted to an aluminum crankcase. Instead, to save weight over that construction, Kales tapped his aircraft-engine experience to cast the crankcase, block, and heads all in aluminum. Forged-steel bore liners, so-called “wet liners” as they were surrounded with coolant, were retained by the cylinder heads.

Since the redline was a modest 5500 rpm, dual overhead cams were deemed unnecessary. Instead, to further save weight, a single camshaft supported by nine bearings operated all 32 valves. Finger followers nudged the intakes, while each exhaust valve was opened by a cam follower moving a horizontal pushrod in touch with an outboard rocker arm. This clever arrangement had never been used before the Auto Union V-16, nor has it been seen since.

The two valves at the top of each cylinder were spread 90 degrees apart inside each hemispherical combustion chamber. While the small bore and domed combustion chambers minimized heat loss to the cooling system, Auto Union’s decision to go with a larger cylinder count did increase friction over competitors’ inline-eights.

To spare the weight of an intake manifold, a semicircular channel ran the length of the engine between the heads. Fed at its aft end by a Roots-type supercharger, this passage delivered the fuel-air mix prepared by a side-draft two-barrel Solex carburetor to the cylinders via short intake ports. Backfires were a real danger, requiring a novel solution. In those days, they were caused by the carburetor’s inability to respond promptly to abrupt changes in throttle position, such as a quick lift to arrest a sliding tail out of a bend (the Auto Union was notoriously squirrelly). Air and fuel mixtures momentarily went out of whack, causing the engine to stutter, a pop you can hear in many carbureted cars from either the exhaust or the intake.

When the Auto Union’s cylinders misfired, it sent flame from the combustion chamber back up the intake and ignited the fuel-air mixture within, to potentially disastrous results, especially for the supercharger. Thus, a simple spring-loaded plate was added at the channel’s forward end to vent the excess pressure of the misfire to the atmosphere before it could do damage. It also served as a wastegate to limit the peak boost reaching the cylinders. One bad side effect was venting toxic fuel to the atmosphere, which sent a trail out the back of the car and into the face of anyone attempting to pass. Thus, the great Tazio Nuvolari raced with a wet handkerchief in his mouth to minimize ingestion of this stuff. He suffered from severe asthma and coughed blood while racing, often staining his yellow jersey. Nuvolari was seriously allergic to the fuel constituents common in the 1930s.

One pump scavenged oil from the pan for cooling and containment in a reservoir, while a second pump delivered lubricant to the V-16’s moving parts. Block skirts extended well below the main-bearing bulkheads to enhance the engine’s stiffness. The lower edge of this casting dropped at a 7-degree angle below horizontal to provide extra material at the rear where the engine was bolted to a five-speed transaxle.

A forged alloy-steel crankshaft supported by 10 main bearings provided one throw for each pair of I-section forged-steel connecting rods. The engine could have gotten by with nine main bearings, but an extra main bearing was added to support the clutch and flywheel, located aft of a gear-driven vertical shaft that spun the overhead camshaft, supercharger, oil pumps, and pair of Bosch magnetos. Flat-topped pistons fitted with three rings were held to the rods by full-floating wrist pins.

By early 1934, Auto Union’s Type A racer was ready for competition. Its 500-pound, 4358-cc V-16 sported a 68-millimeter bore and a 75-millimeter stroke. A 7.0:1 compression ratio with 9 psi of boost yielded 295 horsepower at 4500 rpm and a mighty 391 lb-ft of torque at only 2700 rpm. A table-flat torque curve allowed lapping most tracks using only two gears, and tight courses such as Monaco could be driven entirely without shifting. Mercedes drivers revved their 3360-cc W25 straight-eights a full 1200 rpm higher to achieve a peak output of 314 horsepower, but they fell 10 percent below Auto Union in torque production. None of the French and Italian rivals topped 250 horsepower at this juncture, so despite the V-16’s extra complexity, the design gambit was outwardly successful in packing more torque within the rule limits.

Gasoline in the 1930s lacked the octane necessary to forestall detonation, so a witch’s brew of fuel was used consisting of 60 percent alcohol, 20 percent benzol, 10 percent diethyl ether, 8 percent gasoline, and traces of toluene and castor oil. Since that concoction’s energy density was lower than gasoline’s, the Auto Union’s 55-gallon fuel tank required at least one refill per race.

As a warmup exercise, driver Hans Stuck (father of the more contemporary pilot Hans-Joachim Stuck) ran his Type A open-wheeler to 157 mph on the Milan-to-Varese autostrada before setting a 135-mph one-hour endurance record at Germany’s AVUS track in March 1934. Still, Mercedes remained a fierce competitor, harnessing its greater resources to enter more and better-prepared cars piloted by talented drivers to win four GP races in the 750-kilogram formula’s inaugural year versus three victories each for Auto Union and Alfa Romeo. Fortunately, the Porsche wizards had designed their V-16 with ample room for growth. As competition intensified in subsequent seasons, much more power and torque would be needed to seize the laurels.

Responding to Benz’s first-season success, Auto Union fielded an upgraded Type B for 1935 with the bore increased from 68.0 to 72.5 millimeters, compression raised from 7.0 to 8.25:1 via domed pistons, and two additional psi of boost. Sixteen pipes now spit exhaust thunder skyward. Revving this 4951-cc V-16 to 4800 rpm yielded 375 horses, while torque climbed to 478 lb-ft at 3000 rpm. By midyear, the team implemented another upgrade for use on speed-record runs, a stroke increase to 85 millimeters, which hiked the total displacement to 5610 cc.

In the interests of durability, the connecting rods were upgraded to stronger single-piece units with an integral cap, each fitted with 28-needle roller bearings at their big ends. That, in turn, necessitated use of an assembled multipiece crankshaft to facilitate slipping a pair of rods onto each crank throw. The crankshaft’s pieces connected to each other by means of couplings designed for aircraft engines by Hellmuth Hirth, who trained in America at Edison’s General Electric and helped found the German auto parts giant Mahle. These joints, called Hirth couplings, resembled meshed gear teeth and were clamped together with a through-bolt at the center of each throw. Hours of high-precision machining were required to make each assembled crankshaft.

The relentless Mercedes team also turned up the heat with intensive car development for 1935, resulting in nine season victories versus Auto Union’s four wins in a series of hard-fought contests. Wily Alfa Romeo driver Tazio Nuvolari earned a surprise win at the German Grand Prix on a wet track, an embarrassment to the home teams of Mercedes and Auto Union. Joining Auto Union midway through the ’35 season was former motorcycle racer Bernd Rosemeyer, who proved fearless at the wheel of the loose and demanding Auto Union but who needed time to adapt to the new sport.

Car and driver eventually gelled for the 1936 and ’37 seasons, as Auto Union punched its V-16’s bore out to 75.0 millimeters, yielding a total capacity of 6006 cc, the largest piston displacement used by any manufacturer in this era. At the time, displacement was unlimited, there being no caps until the 1938 season. Wisely, Porsche had entrusted his engine man, Josef Kales, to engineer the V-16 with future displacements bumps in mind, so bore spacing and cylinder-wall thickness were not issues. This new Type C had a 9.2:1 compression ratio fed by 14 psi of boost and pumped out 520 horsepower at 5000 rpm and a potent 630 lb-ft of torque at 2500 rpm. Rosemeyer won the 1936 championship.

Further upping displacement to 6330 cc with a 77.0-millimeter bore gave 545 horsepower in a special Type R engine used mainly for record breaking (though Auto Union may have also slipped that V-16 into a car for a couple of races). As always, painstaking diligence finally earned rewards: six victories in 1936 went to Auto Unions to Alfa’s four and Benz’s two. The following year, once Mercedes finally got its new W125 up to speed, the Stuttgart star scored seven victories to Auto Union’s five.

After the 1937 GP season’s dust had settled, Mercedes and Auto Union continued their rivalry with streamliners, competing on a closed section of the autobahn north of Frankfurt, Germany. Rudolf Caracciola was first out on a chilly January morning with a two-way run averaging 269 mph, establishing a new 1-mile speed record. A few hours later, Rosemeyer took his shot, achieving 267 mph warming up his V-16–powered ultra-low-drag Auto Union. On the first leg of his record attempt at an estimated 270 mph, an intense crosswind bunted Rosemeyer’s car off course. As his streamliner tumbled out of control, the 28-year-old fair-haired Rosemeyer was spit from the cockpit. The exact spot where he perished with a broken neck is marked by a memorial at a rest area near the Mörfelden-Langen autobahn exit.

Considering the 200-plus-mph speeds achieved on long circuits, and the number of drivers killed in action, rules makers were forced to tap the brakes on Grand Prix racing. For 1938, naturally aspirated engines were limited to 4.5 liters while blown powerplants could be no larger than 3.0 liters. By this time, the Porsche organization’s assistance had moved to Mercedes, so Auto Union engineers had to comply with the new rules on their own. Their remarkable V-16 was replaced by an interesting new 3.0-liter V-12. The wider 60-degree V-angle necessary to achieve even firing of the V-12 meant that now three camshafts (one per head for the exhaust valves and a single central camshaft operating the intake valves via finger followers) were needed to open the more widely spaced valves. The new short-stroke crankshafts had roller bearings at both rod and main locations. A smaller cast magnesium supercharger was driven 2.4 times crank speed to produce 17 psi of boost, yielding 460 horsepower at an ear-tickling 7000 rpm. A new two-stage supercharging scheme was implemented halfway through the 1939 season to deliver 500 horsepower at 7500 rpm and 405 lb-ft of torque at 4000 rpm.

Mercedes fielded comparable power in a new W154 racer powered by a supercharged 2962-cc V-12. Once again, the Stuttgart steamroller was not to be stopped. The Benz boys earned a dozen wins in 1938 and ’39 versus Auto Union’s four victories. The red flag finally dropped on this era in September 1939, when the Nazis invaded Poland to begin World War II.

Nearly every trace of Auto Union’s racing glory was annihilated by relentless bombing followed by the seizure of anything of value as reparations. After a 25-year hiatus, the four-ringed logo finally reappeared in 1965 on Audi road cars. More recently, Bugatti, a sister brand under the VW Group umbrella, has thrived building remarkable W-16s, but in light of the current rush to electrification, the days are numbered for these distant descendants of Auto Union’s mighty racing mills.

wow, tell my brother the next empeor of austria, arnold. that vw. is dead. detals later. i think i seen his mom. im in peoria library. on computer. dollar shot. auto union is now what used to be poria. thanks kinkv of england. we are going to duplace this great car with safty latedr. great artice.