Media | Articles

10 Factors That Influence an Engine’s Character

The engine is considered the heart of a car, and while the analogy does work, it starts to fall apart once you get beyond the superficial. The human heart is a relatively boring necessity that is at its best operating with no interesting quirks, flutters, or rhythms. I don’t want my heart to have much personality. My engines on the other hand, well, those had better be interesting. That desire got me thinking about what defines the character so many of us seek from our power plants.

Engines are just a bunch of parts interacting in a way that produces motion. Over the years engineers have discovered ways to make engines more efficient, more powerful, and more reliable by fiddling with a number of factors. Consider each of the items below as a slider on a sound mixing board, able to be turned up or down, or on and off, and how every engine is unique in how these 10 factors are set on every engine out there.

Aspiration

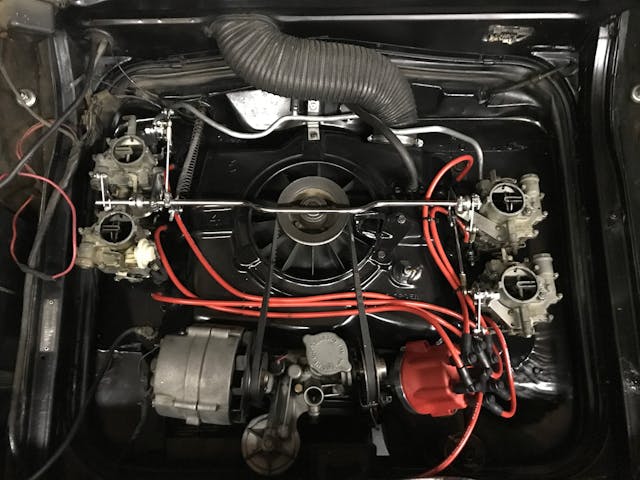

How an engine breathes is critical to how it makes power. Naturally aspirated engine rely on the vacuum created as the engine rotates to draw the air and fuel into the cylinder. Forced induction pressurizes the intake and crams more air and fuel into the cylinders. Forced induction also affects throttle response—looking at you turbo lag—and sets other parameters that the engine must adhere to. In addition to initial responsiveness and power delivery, induction noise plays a huge role in an engine’s character—some can’t get enough of the whoosh a carb or individual runner throttle body setup provides, while the boost and purge of a tuned turbo setup is hard to ignore.

Camshaft profile

The camshaft determines the opening and closing of the valves that flow air and fuel through the combustion chamber. When and how much the valve opens can radically change the behavior of an engine. Opening the valve more can allow more flow through, and thus a higher power potential, but it takes time to open and close the valve. Modern engines are tight enough tolerance that if a vlave is open when it should not be the piston will hit it and that is a bad day. Even making adjustments within that window can radically change the power delivery of an engine. Big camshafts have distinct sounds and often move the peak horsepower high in the engine RPM range, while smaller cams enable smoother power at low rpm but lack the lope that turns heads when you arrive at a cruise night.

Cylinder count

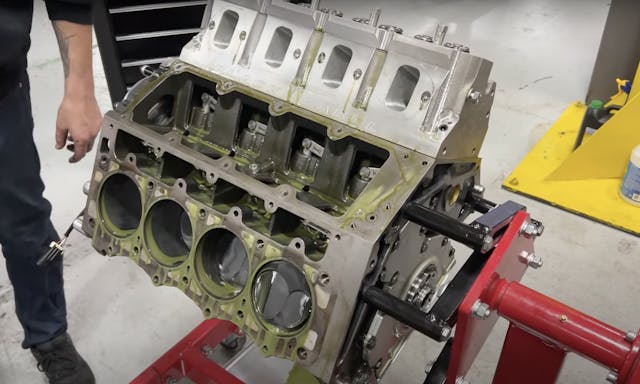

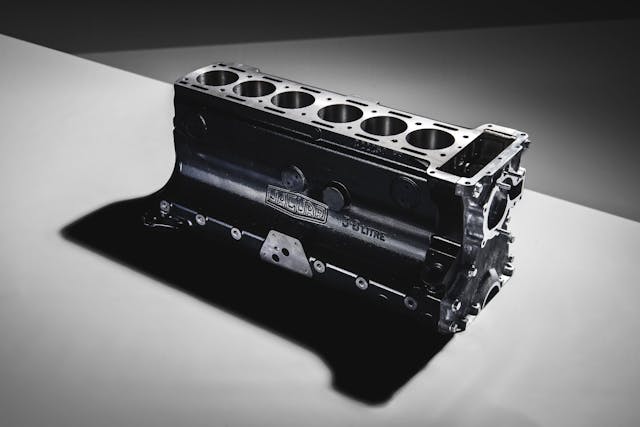

How many cylinders do you need? How many do you want? The answer is often different to those two questions, and that’s okay. A V-8 just has something unique about it that a V-6 just can’t live up to, and an inline-6 charms in a way that an inline-4 can’t. More cylinders often means smoother running since the power pulses on the crankshaft are closer together throughout a rotation. Cylinder count also impacts how the intake and exhaust are routed, creating the signature sounds that accompany many popular platforms but also limiting or boosting performance based on flow characteristics. While more cylinders often run smoother and have more linear power delivery compared to fewer cylinders, 48 might be too many.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Displacement

How big of an engine do you want? More accurately, how big do you want the inside of your engine to be? The cumulative swept volume of the cylinders is how we determine the displacement of an engine, and that also aids in determining a lot of the character. Larger engines often have a higher power potential because they can pull in, burn, and exhaust more air and fuel on their own. Larger displacement also means larger and therefore heavier pistons, which can make for a slower-revving engine.

Crankshaft

The crankshaft converts the reciprocating motion of the pistons into continuous rotary motion we can use, but not all of them are built the same. Many V-8 Ferraris, along with the most recent Mustang GT350 and Corvette Z06 feature flat-plane crankshafts, which facilitate higher and quicker revving compared to a cross-plane crankshaft, which is heavier due to the counterweights required to keep everything in balance. A crossplane design tends to help low-end torque though, something far more usable in a street-focused car.

Cylinder arrangment

With the parameters above picked, it’s now time to decide how you want the engine to be packaged. Anything from boring or pretty wild is available here. From horizontally opposed to a W arrangement that sets up multiple banks on tight angles, there is no end to the options. That said, there are reasons V and inline arrangements dominate production these days. Ease of production and durability win out, but these also tend to be fairly efficient designs.

Compression

Air and fuel will create a small amount of power if burned uncompressed, but that power is fractional compared to compressing the mixture before applying spark. When the fuel burns, it expands and acts on the piston to create power. Achieving maximum squeeze means maximum power, but be careful: Compressing air and fuel too much can cause detonation if it lights off before the spark plug arcs. Low compression engines tend to be slower revving, while high compression lends itself to being snappy but often requires an adjustment to the…

Fuel type

There are four popular octane levels available at most self-service stations: 91, 89, 87, and diesel. Fortunate states get 93, too. The octane rating roughly correlates to the fuel’s resistance to detonation. Diesel fuel is compression ignition rather than spark ignition, so that doesn’t really have an octane rating, but instead uses a cetane rating to describe the fuel’s qualities.

Fuel delivery

How the fuel gets into the engine is also something that has a lot of effects. The smooth pickup and running of fuel injection can be quite nice, but carburetors still get the job done and when properly tuned can be smooth and powerful. So long as the fuel is atomized well, it’ll burn right, but it’s the adjustable choke point for the air that can really affect feel. That’s why the last item is…

Throttle activation

The earliest cars didn’t even have a throttle as we know it today. Engines ran wide open and a clutch and transmission allowed that to be turned into useful power. As engine design improved it became necessary for driver-controlled throttles. Mechanical linkages like rods, levers, and cables were popular until electronics took over engine controls and drive-by-wire became the norm. A physical connection to an engine can be felt be someone with a well-calibrated foot, but drive-by-wire has its strong points, as there will basically never be slop in the linkage and a few clicks on a laptop can tune throttle response.

***

Check out the Hagerty Media homepage so you don’t miss a single story, or better yet, bookmark it. To get our best stories delivered right to your inbox, subscribe to our newsletters.

I’m a neanderthal (or some such other term such as luddite or dinosaur), but I do love the lump of a big cam. Oh sure, I can be tempted by a screamin’ V-12 now and then, but at the end of the day, give me high lift and lopa-lopa-lope!

Every lopa-lopa-lopa car I’ve ever had have been finicky little devils. Now I am partial to a nice, low, stable idle

I didn’t say that they are practical, reliable, efficient, or reasonable. I just said the sound of them makes me feel good. 😁

Knuckle dragger 😊 me too, love a big lopey cam sound!

I’m there too! Replaced the disintegrated 5.7LS1 in my ’04 GTO (Brained Raceway, my fault, missed the 1-2) with a Blueprint 7.0, spec’ed a CompCams roller to mimic a ’60s Pontiac with a RamAir IV+ cam. With the factory driver’s side exit 2.5 duals, I’m giving up some power… but the noise it makes? Ooooh, yeah. And like the lil deuce coupe, can twice stripe in the first four.✨🤘✨😋

How would you like a ’37 Ford street rod pickup with a nice lopa-lopa Chevy 502 cubic inch motor in it? I know where one is for sale. 🙂

I wouldn’t.

Bastardization of a classically-styled vehicle with such a powerplant leaves me disappointed… unless it is built for drag race duty. Otherwise, the combination is merely an impractical one. Hint… it’s for SALE.

These days variable cam profiles, like VTEC or VVTI, allow a car to have that top end power of a big cam with the ability to start, run, idle, and sip fuel at low RPM’s of a smaller cam. They don’t have that idle sound, but they also don’t have to be revved up to over 2000 RPM’s to have more power than a lawn mower either. I’m looking at all of you boom, boom, rev guys.

Absolutely. I had an indelible impression made on my heavy browed head at 14 years when my neighbor brought home a ’70 Cuda with a twin carb built 426 Hemi. (think orange and black AAR without the stripes and a Sox and Martin stance. Hey the car was only 8 years old at the time) I had stayed to closing on afternoon at the local Chrysler dealer coveting that very car in the showroom. To hear it run was like when colour entered the Wizard of Oz. The neighbor left daily for work at 7am, often with the headers open. (Dad was not so impressed as I) and that sound was my alarm clock in junior high for many months. There was no way to resist. Years later and working in the car repair business I was looking for a good used MGB (I know) and I came across a very tidy and nasty looking ’70 Maverick in traffic. Steel blue, Centerline wheels with a Dyno Don stance. I pulled up to read the number on the for sale sign in the window, heard the idle, forgot about MGs. For the record that high compression, lumpy cammed 400HP 302 never gave me trouble. I even drove it to work quite a few times. I just made sure to keep the valves set and the carb clean. It ran great and was very fuel efficient. Ok, I’m lying about the last part but it gave at least 20 smiles to the gallon.

One major factor is the degree of the v in a v block based on cylinders and firing order.

Case in point a 90 degree V6 will often need a balance shaft to control the vibration in the engine where a 60 degree can run free.

The other issue is specific sizes work better that is why you see a lot of 2 liter 4 and 3 liter v6 engines.

There are many engineering aspect that come into play.

You’re actually talking third order vibrations that is not just a function of the firing order itself, but the degrees of crankshaft rotation between firing order to prevent conflicting force. The natural angle of a V6 is 120 degree bank angle and rotation between firing order, a secondary is 60 degree block. Balance shafts used in 90 degree V6s offset uneven 3rd vibrations from a semi-even firing order. Each firing sequence is not 120* of crankshaft rotation from the next, the offset them 108/132. This is better than a 90, which in odd-fire has 2 wide gaps.

Inline 6 engines have torsional harmonics, worse so in straight 8s, impacting higher RPM operation.

The other point missed was the bore x stroke ratio. An oversquare (bore>stroke) will have more high rpm power and less low end torque vs an undersquare (bore<stroke) will have more low end torque and less high rpm power.

And a ‘square’ engine is the best, for my dough — or slightly over-square. I really liked my ’65 Pontiac 326, but it had the 389 crank/stroke vs. a smaller bore, which I didn’t consider ideal. Sure would pass other cars at seventy, though!! Whoosh! (Did you know that the ’63 326 had bigger bores, and was actually a 336?_I’d always assumed that the two ‘small’ big-blocks used piston sizes from the ‘fifties, but don’t think so. Anyone know?_ Amazing, my ’61 Tempest coupe with the Buick 215 V-8 weighs about 130 lb. less than a SBC, but is physically the same dimensions outside! Wick

Thank you James – we had a ’63 Lemans w/ “326” but did don’t know about the possible “336” displacement. For sure that rather small car, 3-speed stick transaxle, moved out nicely.

oops, make that GMC used the Pontiac V8 in 336 cu in form in 1958…

I’m surprised nobody has mentioned the early 60s Pontiac Tempest also came with a 195 CID four cylinder. That was actually designed from the right half of the famous 389 V8. Same head, pistons, rods, head etc. even solid lifters. I had a 62 “back in the day” .

I suspect the 63 Pontiac 326 (336 cu) was because GMC was using that Pontiac engine as a 336 at the same time, so it was a no brainer to share pistons for that year. Just a guess with nothing to back it up.

Any Engine that you can actually see ,(without a plastic cover that hides a hideous arrangement of hoses, wires, tubes & whatnot) has character. So you have to go back quite a few years.

There are a lot of things that influence the character of an engine. Many you’ve mentioned in brief plus others. One that seems worthy of mention is exhaust. Seems like that cat back system is one of todays day two mods. Although often I doubt whether many are actually improving performance. Bigger, as we all know when it comes to intake/exhaust flow, isn’t necessarily better. That fine tuning makes all the difference. I’ve also noticed some aftermarket manufactures emphasizing sound over performance enhancement. I’ve heard some cars with those big three inch systems that sound more like dump trucks and I find it hard to believe that the character and seat of the pants feel hasn’t been sacrificed as well.

Exhaust do make a difference. I had to replace my exhaust on my ’85 Vette. On the way down to the shop, I was getting 21.6 mpg.. After the installation of 2″ stainless steel system, I got 26.1 mpg… and that was going uphill to my home! And that’s a 20.8 % better mileage.. New and larger diameter exhaust systems do make difference!!! At least on my Vette..

Especially headers!

Possibly the expectation of the engine’s character is also in its name – Fireball, Dynaflash, Hemi, Wedge, 6-Pack, Rocket-Fire, Blue streak(??)etc.

The biggest and often overlooked factor to influence an engines character is government mandated CAFE standards.

Fuel…you missed Non-Ethanyl. My 75 Mercedes 450 SL is a totally different engine with the BEST ethanyl laced fuel…once replaced with a good grade non-ethanyl. That corn crap and an old engine were never meant to be together.

Well the whole torque curve / horsepower thing influences the character of the motor. High revving NA motor, torquey down low pushrod power. Sure the layout and design influences those numbers but in and of itself they are a characteristic too.

An engine must reflect the nature of the car that it’s in. My 87 Bertone (Fiat) X-1/9 had a fuel-injected 1.5 Liter. Nice but the same mill could be found in a family car. Throw out the FI and add dual Webers, replace stock cam with performance grind, add an exhaust manifold and flow thru muffler for just the right sound and you have a motor that reflects the true nature of an Italian sports car.

Which is closer to my ‘73 Alfa GTV.

Windage and negative vacuum pressure internally. I switched to a 5 gang dry sump system and an oil pan with separators between each crankshaft journal. With 10 inches of negative pressure and no oil flopping around in the pan against the rotating assembly the engine made an extra 30 horsepower with no other changes.

When I open a hood & I can’t see the engine for all the crap covering it up, I simply close the hood & look for something older.

Agreed!

I prefer manageable performance all the while without constantly having to fiddle around on an ongoing basis with air/fuel tweaks and having to keep my fingers crossed that my precious wheels don’t strand me out in the middle of nowhere. Cars are a love-hate thing. I prefer the love end of the hobby. Guess I’m saying there’s nothing like having fuel injection and breakerless ignition on a classic car that never came equipped that way to begin with. Happy Motoring!

How about adding performance chips that modify multiple aspects of a motor without the need for engine out modifications?

Lets don’t overlook flywheel weight, which can significantly impact the way an engine feels and sounds.

Flywheel weight does affect an engine’s characteristics. Caution must be taken prior to removing mass. I had an engine the someone installed a very light flywheel on. The was insufficient mass to smooth out the power pulses. The consequence was dramatic. The cam gear was being molested by the crank gear. This was so violent that the pressed on cam gear was actually being driven off the camshaft and the teeth that messed with the crank-gear were being destroyed. Fortunately, I stopped just before experiencing catastrophic engine failure.