Media | Articles

Wills Sainte Claire: A forgotten feat of American engineering

I sometimes wonder if we’ll progress as far in this century as we did during the last one. Then, America went from a largely agricultural society to walking on the moon. Charles Lindbergh flew the Atlantic in 1927, and 20 years later, Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier. The progress of cars from 1909 to 1919 was likewise so astounding that it resembled the early tech boom in Silicon Valley. Guys like Henry Ford, Ransom E. Olds, and Louis Renault were the Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, and Bill Gates of their time. I find their stories so fascinating, which is why I own a bunch of their cars.

I thought of this the other day because we just finished a great restoration. Here’s the story: A guy called me a few years ago and said he was selling his grandfather’s antique car, and would I like to buy it? I said, “What is it,” and he replied that it was a Wills Sainte Claire. Right away, I was intrigued. For those who don’t know, Childe Harold Wills was an early engineer and metallurgist for Henry Ford. His mother was a fan of Byron’s poetry, which is how he got the strange name, but Wills preferred to go by Harold. Anyway, while working for Ford, he helped develop vanadium steel, a stronger form of steel that Ford famously used in the chassis of the Model T. Wills also designed the original blue-oval Ford logo.

Both Ford and Wills became extremely rich, but by 1919, Wills was restless and wanted to strike out on his own. He cashed in his Ford stock, pocketed $1.6 million, grabbed a few other Ford people, and started C.H. Wills and Co. in Marysville, Michigan, which is on the St. Clair River north of Detroit. Wills designed the logo, a northern gray goose in flight, calling the birds the “wisest, freest traveler of the skies” as they migrated over Marysville searching for golf courses to crap on. He also added the “e” to Saint Claire to class up the name, and offered lavish benefits to his workers for the time, including housing and healthcare.

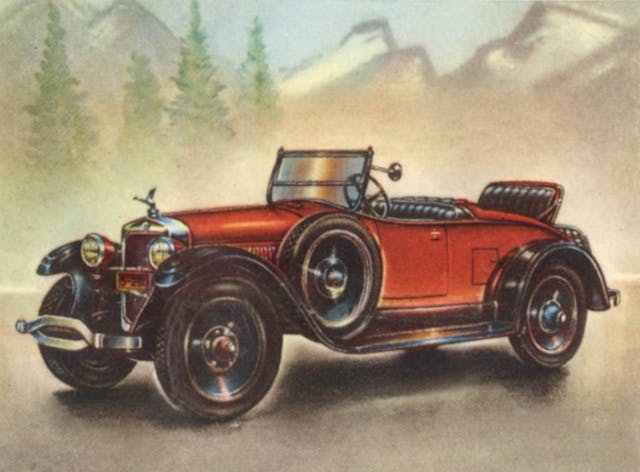

The first car didn’t appear until 1921 because Wills was a renowned perfectionist. First of all, vanadium wasn’t good enough; he was already on to molybdenum to make his steel even stronger. And then there was the engine. Wills was intent on offering a V-8 10 years before the Ford flathead debuted. Unlike the simple flathead, though, Wills’ engine was incredibly complicated. He had become a fan of the Hispano-Suiza 8, a 718-cubic-inch water-cooled single-over-head-cam V-8 widely used in aircraft during World War I, and he decided his new luxury car should have one like it. As with the Hispano, Wills’ own 265-cubic-inch V-8 had overhead cams driven by shafts and bevel gears. It also had a one-piece cylinder-head-and-block construction, which eliminated the head gasket but meant that doing the valves is like going to the proctologist for dental work—you have to come in through the bottom. It doesn’t look like anything American from 1922.

Henry Ford said that Wills’ car was too complicated both to manufacture and for the average mechanic to work on, and in 1921, few people wanted to go 70 mph anyway. He was right. By the time Wills got through, his $3000 car was in the Packard, Peerless, and Pierce-Arrow class, but it looked like any car from the 1920s. It was nice, but not Packard level—until you opened the hood. Wills was out of cash and shut down in 1922 after building only 4400 cars, partly because he kept halting the line to make small changes. Most of his Ford cohorts had taken off when he got going again in 1923, developing a cheaper overhead-cam inline-six. But he never made enough cars to turn a profit. The company disappeared in 1927, and Wills went on to work on the crazy front-drive Ruxton as well as at Chrysler.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

My car spent years locked in a sea container out in the desert being nibbled and urinated on by mice, which corroded everything. But we managed to bring it back. Only 80 of these cars survive. I just like it because everyone remembers the European pioneers like Henry Royce and Ettore Bugatti, but so many early American heroes have been forgotten. Not here.