Media | Articles

Two Cadillacs bear witness to the reinvention of the car in the 1970s and ’80s

Automakers don’t sell cars so much as they sell novelty. Because, you see, most people who need an automobile already have one. That state of affairs explains everything from cup holders and puddle lights to hood scoops and torque-vectoring all-wheel drive.

There’s nothing wrong with novelty. Without it, we might all be living in East German–style apartment complexes, eating government-surplus cheese, and driving beige Corollas. Yet the neon NEW signs flashing in every corner of our collective consciousness can blind us to substantive progress, which comes around far less often and can look less glamorous.

It can, for instance, look like the two cars pictured here: two Cadillac Coupe DeVilles, built 10 years apart. Neither car was the stuff of bedroom posters in its day, and neither is worth a fortune now. More than any Lamborghini Countach or Ferrari Testarossa, though, these two Cadillacs represent the reinvention of the automobile that took place during the 1970s and 1980s—and the costs that came with it.

To understand how this change came about and why it matters, it helps to know something about General Motors. The company has been damaged goods for so long, not to mention a political football, that it’s easy to forget what it used to be and used to represent. It was colossal, yes—the largest automaker in the world for seven decades—but more than that, it was everything postwar America admired when it gazed in the mirror: dynamic, successful, respectable, even clever. “General Motors could hardly be imagined to exist anywhere but in this country, with its very active and enterprising people … with its vast spaces, roads and rich markets …and its system of freedom in general and free enterprise in particular,” wrote longtime GM CEO Alfred P. Sloan in his 1963 memoir, My Years with General Motors.

The hubris was mostly justified. The company had popularized many of the features Americans associated with modern car ownership, from the electric starter to the factory-backed loan. Its management structure, which balanced centralized planning with in-the-field initiative, became a trusted blueprint for decision making at large organizations (and it still informs companies like Amazon).

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Perhaps most important, GM was, for better and for worse, the automaker that truly figured out how to market novelty. Whereas Henry Ford whittled down paint choices in the name of assembly-line efficiency, GM created the first in-house design department to make sheetmetal as fashionable and fast-changing as Parisian skirt lengths. It amassed a fistful of brands and strategically tiered them to tap into every stratum of America’s massive middle class. Last but not least, it promoted the simple yet ingenious idea of annual model changes. By the mid-1970s, the General had controlled nearly half the country’s car market for a generation and had turned the basic, body-on-frame car into a perpetual profit machine.

Most profitable of all were Cadillacs like Tom Manzo’s 1976 Coupe DeVille, pictured here. Cadillac sold more than 100,000 of them back in the day, though few survive in as lustrous condition as this recently restored example. Freshly painted in a brilliant shade of burgundy and stretching nearly 20 feet (3 feet longer than Manzo’s garage), it struts around our golf course photo locale like the royalty it is. The fact that its size serves hardly any practical purpose—we’re talking about a two-door as long as a modern pickup—is entirely the point. At some $9000 new, the DeVille was relatively attainable, costing not much more than the median transaction price of today’s new cars in 2021 dollars. It remains affordable as a classic, with fine examples like Manzo’s going for less than $20,000. Yet driving one, then or now, says you’re living the American dream. Manzo, a 52-year-old president of a manufacturing company who lives in the L.A. area but hails from Detroit, gets the appeal. “I have always loved Cadillacs,” he says. “When you come from Detroit, you have to drive something like this.”

This iteration of the DeVille debuted for 1971, and Cadillac brochures for ’76 touted new features such as a battery that never needed water and door locks that automatically engaged when the shift lever was in drive. However, its mechanical bits differed little from the tail-finned cruisers of the ’50s. “There hadn’t been a meaningful innovation in the industry since the automatic transmission and power steering in 1949,” said John DeLorean in his scathing memoir, On a Clear Day You Can See General Motors.

DeLorean, frustrated with the absence of real change at GM, had quit in April 1973. He should have waited a few months: In the fall of that year, a coalition of Arab nations instituted an oil embargo on the United States. The federal government responded with the first nationwide fuel-economy requirements. The new law, enacted in 1975, mandated Corporate Average Fuel Economy of 27.5 mpg by 1985. Cadillac advertised at the time that DeVille sedans could eke out an “impressive” 15.8 mpg at 55 mph but internally realized it needed to do considerably better.

The 1977 Coupe DeVille, introduced in 1976, was nearly a foot shorter and a whopping 800 pounds lighter. It was an instant hit, in part because Cadillac’s cross-town rival Lincoln had not been able to retool for smaller cars as quickly. “I was in the field at the time, and they were so well received, we were looking at outselling Lincoln three-to-one,” says Alan Haas, a district manager for Cadillac during the late 1970s. The new cars also happened to drive quite well. Even Car and Driver’s David E. Davis, after dismissing the Cadillac as a vehicular “Hickey Freeman suit,” admitted the new one was pretty good: “We loved it in spite of ourselves.”

And GM loved the resulting profits, a record $2.9 billion for 1976, although some of the windfall came via “improved operating efficiencies”—corporate speak for massive layoffs that roiled the Rust Belt.

The reckoning was just beginning. In the wake of the Iranian revolution in 1979, oil prices skyrocketed and the economy tanked. The vast and rich country in which Alfred P. Sloan had grown GM was being described with terms like “malaise” and “stagflation.” It was, suddenly, not at all a land for large Cadillacs. Sales dropped 50 percent for 1980. Frantic half-measures—a self-destructing diesel, a buggy cylinder-deactivation system, the Cimarron—dug the hole deeper.

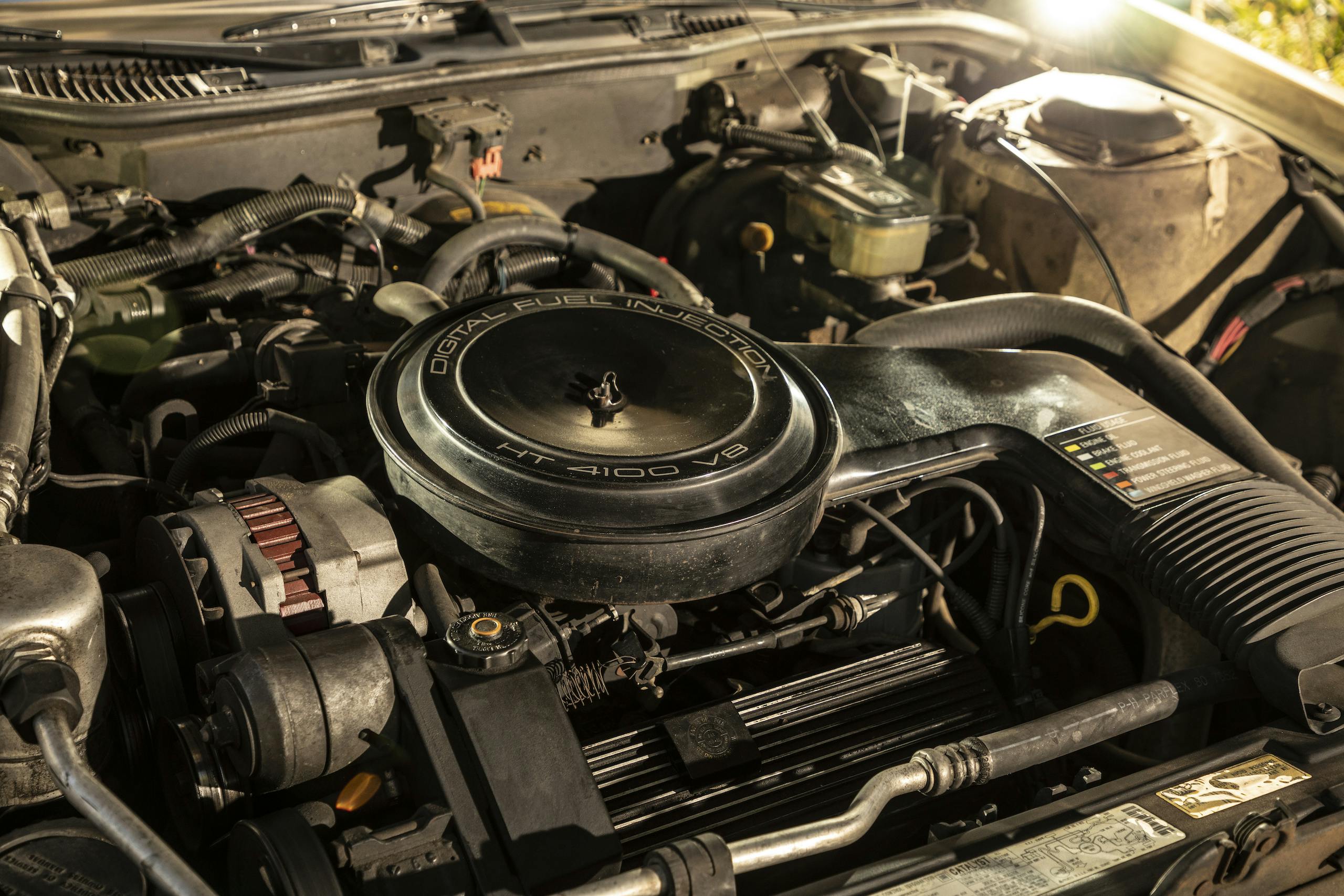

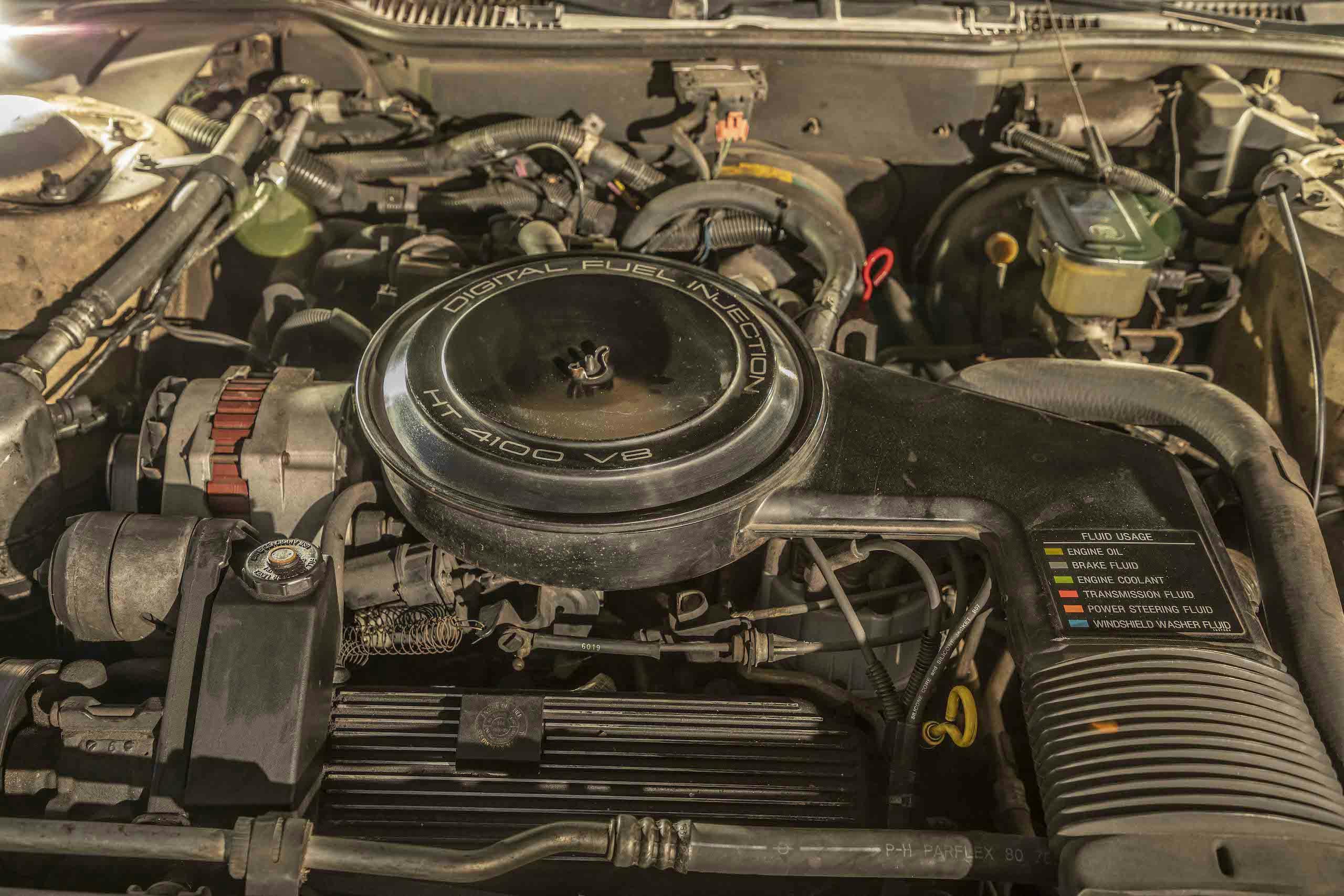

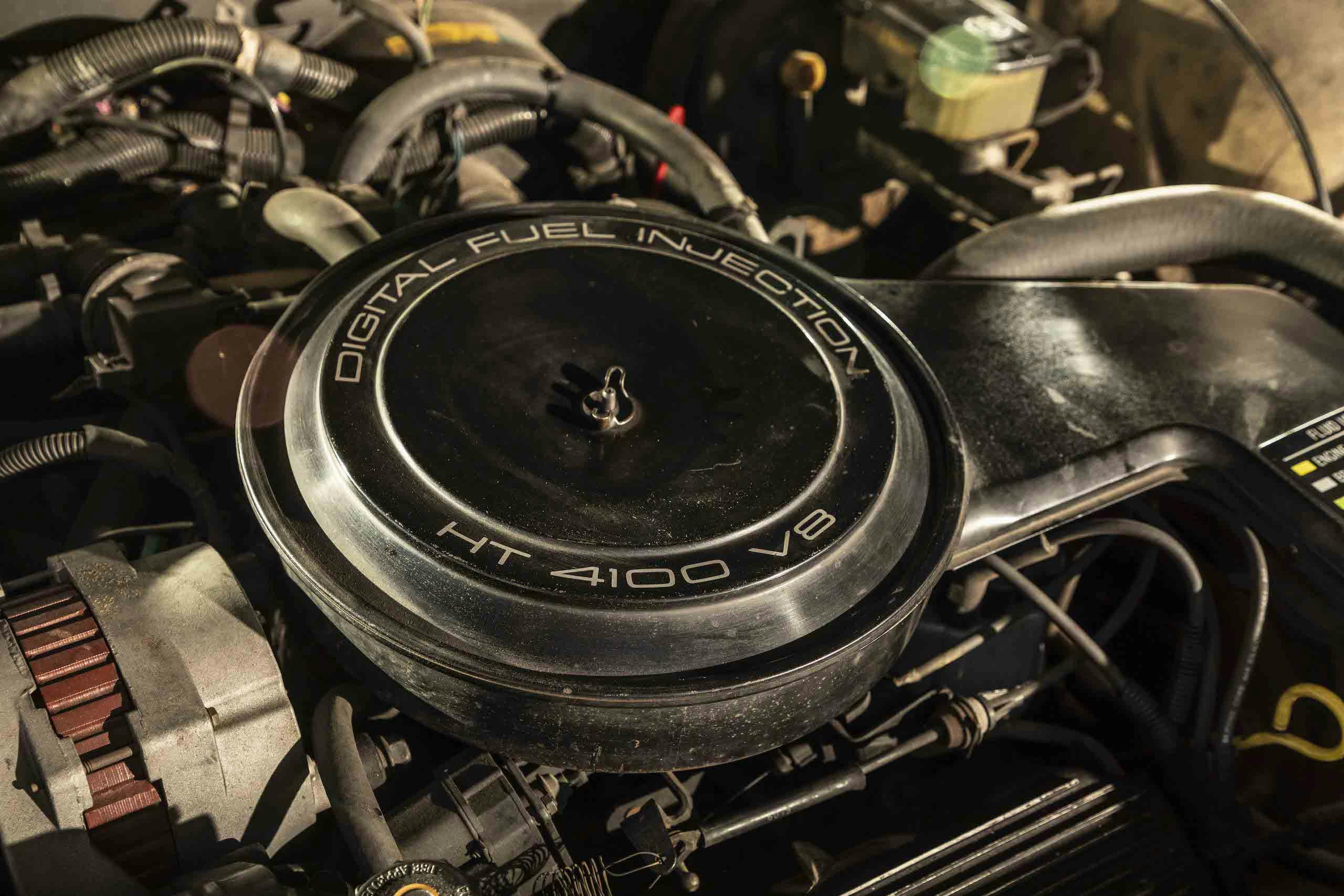

The solution was a second and more extreme crash diet. Full-size Cadillacs now had a front-wheel-drive, unibody architecture. Power came from a transversely mounted, aluminum-block V-8. The resulting 1986 Coupe DeVille was 42 inches shorter and around 1600 pounds lighter than the car that had worn the same badge only 10 years earlier.

“My personal opinion is, we went too far,” says Haas, noting that the most dire predictions at the beginning of the car’s development cycle, such as $4-a-gallon gas, had not come to fruition. Cadillac had, in fact, planned for an even smaller car but widened it at the eleventh hour to accommodate the V-8.

Cadillac attempted to smooth out the transformation by carrying over as much of the old design as possible. Parked side by side, the two Cadillacs look strikingly similar and dissimilar at the same time. Practically every detail of the ’76, from its wire wheels and its landau top and inner door pulls, had been faithfully replicated. That GM designers were able to tailor these cues to a smaller car with completely different proportions speaks volumes to their talent.

In some respects, they did too good a job. The front-drive Cadillacs were panned by the media for looking and driving like much bigger, older vehicles, minus the big-car presence and pizazz. The company that had sold America sizzle for decades didn’t seem to know what to do with real steak.

Indeed, the irony was that the new Cadillac was a true leap forward in almost every measurable way. The Coupe DeVille achieved 31 mpg highway in EPA testing (24 mpg by today’s rubric) yet was about as quick as a ’76. It was much smaller and easier to maneuver, though it had as much room inside. If the advantages of a front-drive, unibody car, such as the lighter weight and vastly improved interior space and trunk, seem obvious to you, it’s probably because nearly every car and crossover on the road has followed the same formula for more than two decades. The ’76 DeVille stands out for its hugeness and wild proportions; the ’86 registers as a normal car.

GM skeptics—and there were quite a few by the late 1980s—pointed out that such advances had already found their way into the likes of the Nissan Maxima and Honda Accord, which happened to look and drive better while costing less. Nevertheless, the Cadillacs, precisely because of their conservative dress and cosseting old-world feel, appealed to the still-sizable chunk of the country that was never going to buy a Nissan or a Honda.

That included a couple in Costa Mesa, California, who bought the ’86 Coupe DeVille pictured here. They held on to it for more than three decades before selling it to the present owner: Alfred Facundo, a 23-year-old Californian who might be Cadillac’s dream customer, right down to his black wreath-and-crest cap. He has warm memories of being shuttled around in the back of a contemporary DeVille sedan as a child. Upon graduating from San Francisco State University last spring, he wanted a classic he could afford to maintain and actually drive around. It’s a hit with his entire family—“We all love this car; my mom claims it’s hers.” It also does better on gas than his daily driver.

Let’s not pretend this story has a pat, happy ending, though—or any ending at all, for that matter. Despite its massive modernization program, Cadillac whiffed on a generation of buyers; these days, it sells half as many vehicles in its home market as BMW and Mercedes do. Its wealthiest customers come to the showroom not for its excellent sport sedans but for the body-on-frame, V-8–powered Escalade, which weighs at least 600 pounds more than Manzo’s ’76 DeVille and gets slightly worse EPA fuel economy than Facundo’s ’86. Making significant progress and making people recognize it are different things.

These days, the auto industry again trades on novelty—witness the 38-inch curved OLED screen in the 2021 Escalade—even as it stares over the precipice of dizzying change. More than a dozen major markets, including Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and the state of California, have announced bans on the sale of new gas–powered cars that are set to go in effect within the next 15 years. Those Corporate Average Fuel Economy requirements, meanwhile, haven’t gone away, demanding a 1.5 percent annual increase in efficiency. The incoming presidential administration will almost certainly press for more stringent rules.

To face what comes, GM has dictated that Cadillac develop a full line of electric vehicles. Whether the 119-year-old luxury brand survives that transition is anyone’s guess. “We don’t have any chances left with taking Cadillac to a really new place,” GM president Mark Reuss told reporters at the 2019 Detroit auto show. “This is pretty much it.”

The ’76 and ’86 DeVilles tell us such big leaps are hard to make and not without risk—but also that they’re possible and, perhaps, unavoidable. Even Alfred P. Sloan, peering into the industry’s future from 1963, would not have disagreed: “There is no resting place for an enterprise in a competitive economy. Obstacles, conflicts, new problems in various shapes, and new horizons arise to stir the imagination and continue the progress of the industry.”

1976 Cadillac Coupe DeVille

ENGINE: 8.2-liter V-8

POWER: 190 hp @ 3600 rpm

TORQUE: 360 lb-ft @ 2000 rpm

WEIGHT: 5025 lb

POWER-TO-WEIGHT: 26.5 lb/hp

0–60 MPH: 12.2 sec

PRICE: $9067

HAGERTY #2 VALUE: $16,000–$22,500

1986 Cadillac Coupe DeVille

ENGINE: 4.1-liter V-8

POWER: 130 hp @ 4200 rpm

TORQUE: 200 lb-ft @ 2200 rpm

WEIGHT: 3395 lb

POWER-TO-WEIGHT: 26.1 lb/hp

0–60 MPH: 11.7 sec

PRICE: $20,754

HAGERTY #2 VALUE: $5700–$7300