Media | Articles

These 6 performance parts are true hot rod heroes

The specialty-equipment business that feeds the go-fast habit is a $46 billion industry. We salute some of the pioneers and their innovations that transformed jalopies into rods while building brands that are household names today.

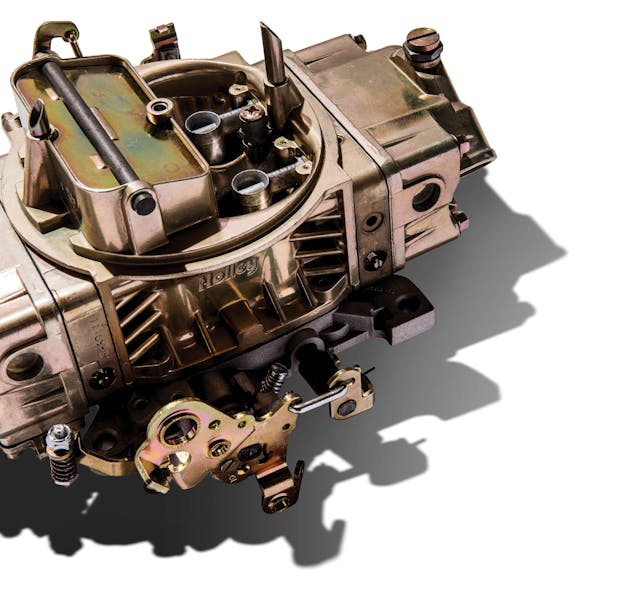

The Holley carburetor

In 1897, only a year after Henry Ford enjoyed a test drive in his experimental Quadricycle, George Holley built and drove a three-wheeler near his Pennsylvania home, topping 30 mph. Two years later, Holley and his brother Earl established the Holley Brothers Company to build and sell motorcycles, followed by the Holley Motorette, a 5.5-hp two-seat horseless carriage. In 1904, this budding enterprise introduced its “iron pot” carburetor for use on curved-dash Oldsmobiles. That fuel-air mixer worked so well that it was soon found on Buick, Ford, Pierce-Arrow, and Winton automobiles.

After selling 600 Motorettes, the Holleys stopped building cars to focus their energies on carburetor production. Legend claims that Henry Ford backed that move, saying, “If you stop making cars, I won’t build carburetors.”

To burn all the fuel during each combustion stroke, engines require 14.7 parts of air for one part of fuel (by weight). Providing that ideal mix throughout the full operating range from idle to the redline and at every throttle setting is no small feat. One could make the case that the carburetor was the auto engine’s hardest-working and most sophisticated component before it was replaced by fuel injection.

Holley thrived by supplying tens of millions of carburetors to Ford and other American makers. When the horsepower race began with the introduction of Chrysler’s Hemi in 1951, Holley responded with its first four-barrel design for the 1953 Lincoln. Holley’s 4150 four-barrel, what some call a masterpiece of engineering and the first true performance carburetor, followed in 1957 on Ford V-8s.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The 4150 is a modular design with ample airflow capacity and astute fuel metering. Through the ’60s and ’70s, Holley never flinched when emissions controls arrived and more power was demanded by Trans-Am and NASCAR racers. The 4150 and its 4165/4175 spread-bore successors still serve classic car owners today.

Building on the respect earned supplying car makers and aftermarket customers, Holley evolved into the hot rod industry’s largest and best-known nameplate. Nearly 40 other brands now operate under the Holley umbrella offering fuel injection, turbo kits, mufflers, wheels, ignition systems, nitrous oxide kits, and brake parts. We’re guessing that the dearly departed brothers would smile knowing that carburetors are still a mainstay product at Holley.

The Flowmaster exhaust

Self-taught engineer Ray Flugger launched Flowmaster in 1983 to create a more efficient motorsports muffler capable of reducing noise at racetracks surrounded by residential neighborhoods. Stock mufflers, which are necessarily inexpensive, inhibit exhaust flow to curb the rumble—to the detriment of horsepower. More creative designs with internal chambers and/or sound- absorbing material such as fiberglass cut the din without impeding flow at high rpm.

Building on experience he gained making mufflers for Volkswagens, Flugger invented several chambered, laminar-flow, and straight-through silencers that allowed customers to fine-tune their performance and sound levels. He followed his motto, “Hit the gas till you see God, then brake!” until he died at age 79 earlier this year. Flowmaster was purchased by B&M, the automatic-transmission specialist, in 2011. That enterprise merged with Holley in 2018.

The Isky camshaft

Ed Iskenderian is showing signs of immortality. At 99, he’s still toting his trademark stogie and still making camshafts under his trade name, Isky Racing Cams. Beginning with the Ford T-bucket he assembled in 1938 to race across the dry lakes north of Los Angeles, Isky has experienced enough speed and power for three lifetimes.

Swapping camshafts was a favorite mod in the flathead days from the 1930s to the 1950s because it was a cheap and effective means of upping power. This shaft opens intake and exhaust valves on cue by means of an egg-shaped lobe aligned with each valve stem. Lifting the valve higher and holding it open longer allows more fuel-air mixture to enter the combustion chamber while also providing a more expeditious exit for exhaust gases.

While car manufacturers configure their camshafts for quiet running, smooth idle, and peak torque at moderate rpm, racers give no hoot about those concerns. What matters buzzing across a miles-long lake bed or around an oval track is peak power during the last few hundred rpm, so wilder cam timing is always better.

Camshafts are manufactured by spinning the shaft while an abrasive wheel is rocked closer—then farther—from the shaft’s centerline, which grinds one lobe at a time to the desired shape. While sophisticated mathematics and automatic controls are used today, trial and error was common practice in the flathead days. In Isky’s words, “Cam grinding is some part science, some part math, some part luck, and a big part educated guesswork.”

After completing his World War II Army Air Corps service, Iskenderian set up in the back of a friend’s shop and modified a $600 grinding machine to manufacture camshafts. Inspiration for how to shape his cam lobes came from studying an Offenhauser racing engine and, later, the pointy end of an egg. When his first $30 “fast action” cam proved successful on the dry lakes in 1946, Iskenderian was off and running. He was also one of the first recipients of the new small-block Chevy V-8 in 1955 to accelerate that epic engine’s adoption by hot-rodders.

Advertising in Hot Rod magazine, artful T-shirt designs, and sponsoring successful racers shot Isky’s name recognition skyward. Isky cams remain in high demand in part because this brand’s distinctive sticker is essential equipment for any contemporary hot rod.

The Edelbrock intake

Imagine running a marathon with one or both nostrils pinched closed. If you’re fit enough to finish, your time will still be far off the mark. Engines must also breathe freely to reach their power potential. The more air and fuel that enters the combustion chamber during each intake stroke, the more power is produced by combustion. In pursuit of better breathing, hot-rodders resorted to multiplying the number of carburetor throats feeding their engines.

Vic Edelbrock wasn’t the first to bolt on extra carbs, but he soon became one of the best at tuning engines capable of setting speed records on the dry lake beds of the Mojave Desert. By 1940, his ’32 Ford roadster equipped with high-compression heads and a 2×2-barrel intake manifold was crowding 120 mph. When manifold maker Tommy Thickstun refused to incorporate improvements suggested by the Los Angeles racer and shop owner, Edelbrock combined his ingenuity and notoriety to manufacture and sell his first Slingshot manifolds, which adapted a pair of Stromberg 97 two-barrel carburetors to the Ford V-8.

Step two was adding cast-aluminum cylinder heads to the Edelbrock product portfolio. Squeezing the air and fuel mix tighter during compression intensifies the bang upon ignition and extracts more energy from the charge during the power stroke. A popular expedient was simply bolting on factory heads Ford intended for high-altitude locations such as Denver, where more compression was needed to compensate for the performance loss attributable to thin air. Taking that idea to its logical end, Edelbrock raised the Ford flathead’s compression further, improved the combustion chamber’s shape, and cast his new heads in aluminum to trim weight. The addition of cooling fins and an attractive Edelbrock product logo made these cylinder caps the ideal accompaniment to a Slingshot manifold.

Twin carbs led to three-in-a-row carbs. After World War II, Edelbrock began servicing drag, oval-track, road-course, and Bonneville racers as his business grew. When the small-block Chevy V-8 arrived in 1955, GM dispatched early production engines to Edelbrock’s shop to give him a leg up making aftermarket speed parts.

Vic Jr. took over when his father died from cancer in 1962. Under his watch, the company grew exponentially by adding carburetors, fuel injection, valvetrain components, superchargers, and exhaust systems to its product range. Unfortunately, Vic Jr. died three years ago, leaving three Edelbrock daughters to keep this revered brand name kicking.

The Hurst shifter

America’s whirling dervish of the 1960s, George Hurst never allowed his eighth-grade education, 11 years of military service, or three wives to slow him down. In 1958, after founding Hurst-Campbell with Bill Campbell, the engineering brains of the organization, Hurst burst into the hot-rod business with three-and four-speed floor shifters engineered to replace the clunky factory equipment. He helped Pontiac become America’s hottest car brand with Hurst shifter and custom wheel adornments. His wild Hemi Under Glass Plymouth Barracuda traded drag-strip speed for quarter-mile-long wheel-stand spectacle. In 1964, he partnered with Smokey Yunick to race a bizarre Indy car with the driver seated in an offset pod positioned between the left-side wheels, and Hurst’s four-engined Goldenrod set a Bonneville record of over 409 mph. By the end of the ’60s, Hurst had partnered with Olds and American Motors, producing the Hurst/Olds 455 plus some drag specials and off-road ventures.

Hurst’s most memorable promotion was appointing Linda Vaughn as his Miss Golden Shifter. She and her 40-or-so accomplices became royal drag-strip queens grasping 10-foot-tall Hurst shifters towering over a custom convertible’s decklid.

After going public in 1968, Hurst-Campbell bought the Schiefer clutch, Gabriel shock absorber, and Airheart brake companies. Appliance maker Sunbeam purchased Campbell’s stock in 1970 to seize control, but Sunbeam and Hurst were oil and water. When the new management expressed disinterest in Hurst’s innovative Jaws of Life car-crash-victim extraction equipment, Hurst walked out in December 1970. Some 35,000 Jaws of Life tools were built and sold, and they saved thousands of lives. Many are still in use today.

Charged with tax evasion, Hurst spent time behind bars in 1971 and served an 18-month prison sentence in the early ’80s. He finally eluded the taxman for good in 1986 while sitting behind the wheel of a car with its engine running inside a closed garage.

That same year, the Mr. Gasket company purchased what was left of Hurst Performance. Like practically all things hot-rod related, these remains made their way to Holley in 2015. New and improved Hurst shifters are still available thanks to Holley’s enduring support.

The Hooker header

Within two hours upon arriving home in his new 1962 Chevy 409, Gary Hooker had stripped the heads off his engine. Since he couldn’t afford to buy headers to hot up his 409, Hooker decided to make his own replacement pipes using longer and larger-diameter tubing than was common practice in the ’60s.

Drawing again on our reference to the challenged marathon runner, headers work on the exhale side of aspiration. In engines, they raise power by diminishing exhaust restriction at high rpm. Headers provide a separate flow path for each cylinder with smooth bends, larger inside diameters, and longer lengths before the individual tubes combine into a common exhaust pipe. When properly designed, the flow from one cylinder helps suck exhaust out of another bore. They are also typically lighter and more attractive than factory exhaust manifolds.

Hooker, an electronics technician at General Dynamics in Southern California, combined his fascination with cars, his drawing ability, and his mechanical insights to outdo existing header makers in the 1960s. Dynamometer and drag tests proved his first 409 design delivered a significant power gain. Only a few months after Hooker had established his first manufacturing shop, six of the top 10 Super Stock drag racers were using his equipment. By 1970, Hooker Headers was a $3 million business.

Without forgetting his racing roots, Hooker shifted his focus to customer satisfaction to foster growth. In 2000, he sold his business to Holley, and he was inducted into the Specialty Equipment Manufacturers Association (SEMA) Hall of Fame in 2012.

Thanks in part to this hot-rod pioneer’s painstaking effort, original equipment makers have upped their game; a case in point is the 2020 Chevrolet Corvette Stingray’s stock headers, which sweep majestically upward before connecting to the catalytic converters. Another advancement in this field is cost-no-object designs such as those by Ultimate Headers, which employ cast stainless-steel flanges and elbows to enhance beauty while accommodating tight engine compartment clearances.

We’ve been damned fortunate to have lived through this period of automotive history.

B.

ET’s and Chambered mufflers.

Grant steering wheels.

and Sun Super Tachs..

What, a 4 year old, retread article!!! 2020, really, you guys getting lazy? Ed Iskenderian just happens to be 102 years old now. Here’s a link that’s a little more recent than your old, rehashed bird cage liner… https://www.caranddriver.com/features/a60884257/ed-iskenderian-documentary-isky/

Baby Moons and then mid ’60’s, Wide Oval tires. Crap at first but got the idea established

Four years later and Isky is still with us – 103 and still kicking!

First reaction: why the specific brand references? Payola? What’s going on here?

Yep, headers, aluminum intakes, quality performance mufflers, and shifters that won’t damage your gear teeth are big performance enhancers, but LOTS of companies produced many of these enhancements before the brands named — even Isky!

I loved my Hurst floor shifts; good, and pretty cheap when first introduced, but Hurst/Campbell wasn’t the first or only company to make quality floor conversions. Edelbrock began early, and always made lots of good stuff in lots of applications, but they took it to the ‘corporate level’ very successfully. Headers; before Hooker, Sanderson, Stahl, Tyree, and others began to sell over-the-counter or even mail-order stuff, beautiful and state of the art exhausts were being turned out by rodders and shops in every decent sized town! And the non-straight-through performance muffler was first instituted by Chevrolet, in their Corvair Spyder, the ‘Turbo Muffler’ and a staple for many years. Holley: fine but there are alternatives, and many as good: remember it was Carter that pioneered the 4-bbl ‘white-cast-four-barrel, or WCFB, and followed it with the aluminim-four-barrel or AFB (now made by that E-company, above). Holley’s first 4-bbl was a grotesque horror that didn’t live long, and is seldom seen except at restoration shows. And don’t lecture me on Holley float-bowl leaks! Take a leaking Holley 4-bbl and a shorted overdrive switch (on my bro’s Rambler Rebel) and you have an incinerated engine compartment!

Kudos to the companies you enumerate but don’t forget the other pioneers, and their contibutions! You must have Holley, Edelbrock, Hurst, Hooker, Isky etc. decals on your laptop, huh? Like we used to put them on our driver’s side quarter windows? I M Humble O Wick

very excellent list…add

Offenhauser.. Nick Arias…Bruce Crower…Hank the Crank…Weiand …Milodon …Mickey Thompson Super Scavengers–headers…Hoosier…Enderle..Kinsler…HalTech…

AND all the fantastic contributors to the genre…. so many more that deserve mention

their sacrifice in time, energy, knowledge, risk, innovation and research was the boon to enthusiasts the world over

God bless and keep them all for the opportunities and making us possible and our innovative craft available

just walk down NITRO ALLEY and meet the approachable crews and families of our distinct calling …

hasn’t changed for the 60 years I’ve been around

Yep all those goodies made Hot Rodding way better and more tickets too LOL

WOW………you hit the nail on the head. I sold so much of those very products in my speed shop for 40 years, I wish I could count how many. Great products. No junk there.

Really enjoyed the Holley carb piece. I hate to show my ignorance but I’d really like to know, in attaining the ideal mix of 14.7 parts of air to one part fuel by weight, how is the air weighed?

I had a Hooker expansion chamber on my 1972 Hodaka Super Rat. I’m not sure the pipe did anything for the bike other than make it louder but the heart shaped logo cut out of the heat shield gave it “cool” in spades.

Recap slicks, who could afford M&H.

MAGNAFLOWS! PERIOD!

To the expanded list I would add M ‘Boots’ Mallory and his first electronic ignition systems & coils.

I have a set of Hooker headers on my old Impala. Kinda had to with my name!