Media | Articles

The Indy 500 has always endured

This story originally ran in the July/August 2020 issue of the Hagerty Drivers Club print magazine. Check out the results from the 2020 Indy 500 here.

Just before the lockdowns and the mandatory masks and the daily death counts, Roger Penske recalled to a dinner crowd at this year’s Amelia Island weekend in early March the moment that Indianapolis Motor Speedway president Tony George suggested that Penske buy the 111-year-old track from the Hulman-George family. “My eyes were spinning,” said Penske, whose father took Roger to his first Brickyard race in 1951. Since then, Penske Racing has won Indy 17 times, and now, at 83, he owns the place. Though hardly known for being sentimental, the stony-faced mogul admitted, “I hope Dad is looking down.”

Alas, a month later and with coronavirus on the march, Penske postponed the race until August 23. “If this thing isn’t over in five months,” he said, “we’ve got bigger problems.” Yeah, bigger problems.

I hear a lot of people say that America is damaged. I try to keep some perspective. Gettysburg was bad. The Dust Bowl was bad. Almost the entire year of 1968 was a disaster. By those measures, our times are not so tough. Penske can take some comfort that his speedway predecessors had to face their own crises while striving to preserve the institution. At least he doesn’t have to worry about German submarines.

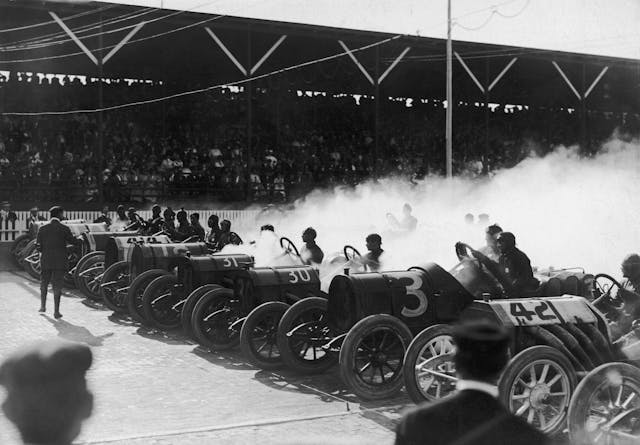

The four founders of the speedway, James Allison, Carl Fisher, Arthur Newby, and Frank Wheeler, were in business just five years before Europe collapsed into war. Interest in racing steadily waned as the world’s attention went elsewhere. Planning for the 1917 Indy 500 faced obstacles ranging from a rancorous dispute with local hotels over price gouging to concern that the ships carrying the Fiat and Sunbeam teams from Europe might get torpedoed. Then speedway management abruptly called off the race two months before the event and a month before the U.S. entered the war.

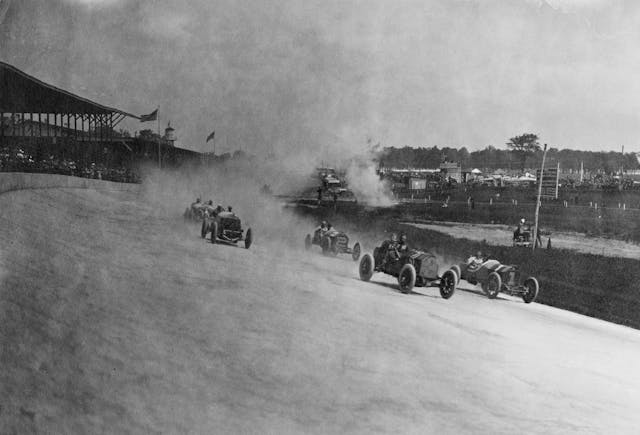

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Though other tracks stayed open, Allison cited “the fact that we will need all our resources in gasoline, oil, rubber, and particularly the best of the world’s motor drivers and mechanics for a more serious purpose.” The partners offered their now-idle 400 acres free to the War Department as an aircraft repair depot, and they donated the surrounding parking areas for the harvesting of victory wheat. Speedway stars like Eddie Rickenbacker and Caleb Bragg, “the former idols of speed-mad thousands,” as the papers called them, went off to war. A few, including French Grand Prix ace Georges Boillot, who went 125 mph in a Peugeot at Indy in 1914 and was last seen tangling with five German Fokkers over the Western Front, never came back.

The war dragged on. As the Indianapolis Star bemoaned in spring 1918, “ another Memorial Day of oppressive quiet and goading inactivity” passed without a race. As today, people had ample reasons to be despondent. A catalog of the daily carnage from the trenches filled the front pages. Other war-related horrors, such as the fate of the RMS Leinster, torpedoed in 1918 in the Irish Sea with more than 500 lost, many of them women and children, only rated inside coverage. As if to seal the mood, an Army plane from the speedway on a PR run to drop baseballs for the start of a local tournament crashed just behind second base, killing the pilot and canceling the game.

Lists of the war casualties began to include an ever-growing number who succumbed to the Spanish flu. In October 1918, it claimed a pillar of the Indy racing scene, “Happy” Johnny Aitken, who had been driving and managing since 1905. He was 33 when the pandemic cut him down, as well as his 29-year-old mechanic, Edward Covington. The news made it as far as the trenches, from which Indiana doughboys deluged the Star with letters of grief.

More than a century old, Indy has seen “bigger problems,” but it has always endured because its caretakers refused to let it die. Penske may not be sentimental, but he is stubborn. Better days are surely ahead.