Media | Articles

Japanese Rock Stars: Three cheap rigs from 1987 go dirty dancing in Utah’s canyon country

It was the age of perestroika. Of peak Michael Jackson. Of U2 and The Joshua Tree and RoboCop and Reagan and the Black Monday Crash that seemed so terrifying back then. It was also a time of body stripes and dashboard inclinometers and five-speeds on everything. It was the time when Japanese trucks were cool.

This all started last year when three friends were talking about the idea of throwing in together on a barn-find Porsche 356C in need of everything. The plan fell apart when one of the friends, Hagerty’s own Logan Calkins (last seen jumping his VW Thing), decided that the Porsche was too much of a sinkhole, and that what he really wanted was a 1980s Toyota 4Runner. Because the 1980s were rad and because, despite the fact that he had already owned 13 Toyota 4Runners, somehow that itch wasn’t fully scratched.

Within a week, he had poured most of his Porsche stash into a 1987 4Runner with “only” 240,000 miles on it. The model year, 1987, was both coincidental and opportune: Another person in the group, Hagerty contributor Lyn Woodward, had recently rescued a 1987 Mitsubishi Montero from a suburban Los Angeles driveway where it had sat for years melting into the asphalt. The group chat about a Porsche devolved into a group chat about how awesome Japanese trucks used to be, when they were simple and rugged and not too big, and before they got soft and car-like and full of cup holders and computer screens.

Not wishing to be left out, your humble narrator hunted down a 1987 Suzuki Samurai, and the stars were thus aligned for a sort of high school reunion. Wrenches were laid to fix leaks and squeaks, and the group discussed what it should do with the trucks. The obvious answer: Leave. Vámonos. Make like a tree and get out of here. But to where? Greater Los Angeles is roughly a hundred miles by a hundred miles. On a map, our eyes followed the freeway out of town, past a lot of empty desert that would make fine adventure territory. But Woodward maintained that the backdrop had to be big to show off the littleness of these old trucks. “Not even Death Valley has enough bigness,” she insisted. So our gaze kept going across the map. Past Las Vegas, through the deserts of Nevada and Arizona and skirting a lot of natural wonder, until we decided, well, we’ve come this far, we might as well go for the mother lode of bigness: Moab, Utah.

The present capital of four-wheeling is an old uranium-mining hamlet at the eastern edge of the Beehive State, which itself is unfairly rich in landscapes best described as Mother Nature cranking the volume up to 11 and breaking the knob off. Canyonlands National Park, to the west of Moab, is 337,598 acres of craggy wilderness dominated by an immense, ocher-colored plateau called the Island in the Sky that divides two western waterways. The Colorado River and the Green River have each cut deep, meandering canyons on their way to a merger at the plateau’s southern tip, where the waters flow on together toward Glen Canyon and the Grand Canyon.

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

The White Rim Road, named for the layer of bleached stone that underlies much of this old mining and cattle-ranching track, traces these rivers under sheer cliffs, weaving among the fins and slender spires of Navajo and Wingate sandstones. The White Rim offers 70 of the most spectacular trekking miles with which you’ll ever roll an odometer. And though it has a few suspension-twisters and a lot of stretches made laborious by nubby rock, the trail is actually not that tough. That was a key factor for old, stock trucks that were built before the off-road industry reached DEFCON 1 with its push-button lockers, rock-smashing suspensions, and humongous tires.

More important, though, Canyonlands is massive and magnificent, a place where humans in three little 1980s trucks would feel suitably small and insignificant, an impression that is growing harder and harder to experience in our shrinking world. And, if we’re honest with ourselves, it’s where we wanted to go from the start of this tale, despite the 13-hour drive from LA. Thus, with our campsites secured three months in advance—you must book them through the National Park Service, and spring and fall are the busy times—we made for Moab in our flotilla of cheap escape vehicles.

The writer Edward Abbey lived much of his life exploring “all that which lies beyond the end of the road” in this area of countless serrated canyons and wind-sculpted arches. He is partially to blame for it being overrun in modern times with geared-up adventurers, having called his dusty red corner of paradise “simply the most beautiful place on earth.” Before Abbey came in the mid-1960s, the uranium wildcatters traipsed over it, cutting roads and digging toxic dogholes at the government’s encouragement. It was the Atomic Energy Commission that built the White Rim Road, using bulldozers to stitch a bunch of old herding paths together. Before the machines came, the ranchers ran cattle here on horses, and before them, Ancestral Puebloans sheltered in its coves and etched their stories on its walls in haunting petroglyphs.

People have always seen what they want to see in these breathtaking panoramas, from mineral riches to grazing nirvana to a homeland where the spirits live eternally in the wind. We saw a rock-hopping good time, so after assembling and provisioning in Moab for a three-day journey, we drove west across the 6000-foot-high Island in the Sky mesa to a snaking descent route cut into the cliff walls that death-drops a truck about a thousand feet into the gorge of the Green River. Taking pictures here at the start of our journey, the photographer noticed a glint of metal in the canyon debris, then the battered tailfin of a—Mercury? It was too far gone to tell. Several other crumpled wrecks lay with it, probably old mine company cars unceremoniously pushed off the edge when the uranium boom collapsed in the 1960s and vast investor fortunes were lost to the whistling wind.

I caught Logan studying the front of his truck with a furrowed brow. “Have you tried out your four-wheel-drive system yet?” I asked.

“Nope.”

“Me neither,” I lied, trying to make him feel better. Woodward volunteered that she had spent so much money fixing other stuff on her Montero yet never replaced the rotted old spare tire.

And with that, we worked the old-fashioned levers and twist-hubs (the deluxe Montero has an automatic transmission and auto-locking front hubs) to engage low gear, then descended to White Rim Road. Many of the names of scenic spots along the trail date to the rancher days, and they speak to the difficult life in one of North America’s remotest job outposts: Horsethief Trail, The Labyrinth, Hardscrabble Bottom, Upheaval Canyon, Dead Horse Point.

The names come rich with stories. Down the river a ways is Harveys Fear Cliff. The tale goes that a cowhand by the name of Harvey Watts had roped a mean bull when he was thrown from his horse and, still clutching the rope, wound up hanging on for his life off the cliff. When he pulled himself up, the bull saw Harvey and made a run at him, dropping him down. When Harvey was out of sight, the bull lost interest and wandered away, pulling Harvey back up. Back and forth it went, long enough for Harvey and his fear to earn a spot on the Utah map.

At Potato Bottom, we rolled past the splitting and desiccated remains of an old corral. Cattle herder Art Murray built a waterside cabin here in 1932, to which his wife, Muriel, scoffed, “Who else would throw up such a rat trap?” After five years, Art became fed up with “the whole thing,” presumably including Muriel, and moved to Canada. Just across the river is Binky Bottom, named for Dubinky Anderson, another cattleman in the 1930s. Dubinky knew a fella named Guy Robison, who while out riding with the herd got stuck in a snowstorm that painted the landscape completely white. Then the sun came out and the glare blinded poor Guy so badly that he had to ride back to the ranch with his eyes closed, just clinging to his horse. Days later, when they stripped the bandages off and Guy’s vision slowly returned, his eyes, which had been brown his whole life, had turned permanently blue. So the story goes, anyway.

The Green River courses implacably through endless writhing twists and turns in the canyon. “The whole country is inconceivably desolate, as we float along on a muddy stream walled in by huge sandstone bluffs that echo back the slightest sound,” wrote one of the area’s earliest white explorers, George Young Bradley of the Powell expedition of 1869. “Hardly a bird save the ill-omened raven or an occasional eagle screaming over us; one feels a sense of loneliness as he looks on.”

The only evidence of human impact during our visit 150 years later is the trail itself and a couple of kayakers making fanning ripples as they paddle along Bradley’s path southward toward what is now Arizona. Actually, another sign that men preceded us here is the bushy tamarisk that lines the riverbanks as dense as thick, green dykes. It’s a water-loving Mediterranean plant brought in decades ago to reduce bank erosion, but now the park service is trying to hack back the pervasive weed to give the cottonwoods and other native flora a chance to return.

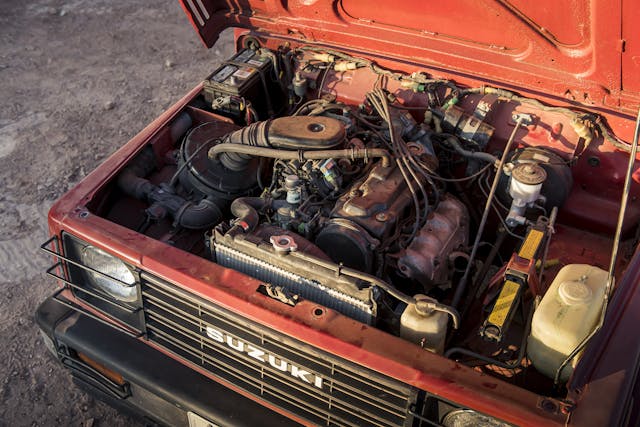

The Suzuki scooted—“bounded is a better word,” insisted Logan—like a giddy jack rabbit deep into this eroded, crumbling landscape of natural splendor tinged by man-made folly. A 1987 Samurai is as close as the modern industry will likely ever get to producing a faithful replica of the World War II jeep. The axles are two small logs suspended by the cutest little leaf springs you ever saw. They are hitched together through a two-speed transfer case engaged with a stubby shifter that almost certainly was rarely touched by the yuppies and Aqua Netted prom queens who first drove these off dealership lots. Ditto the manual hub locks that engage the front axle. The only electronics are the ones controlling the carburetor (of the three trucks, only the Toyota is injected) sitting atop the 1.3-liter gerbil wheel that moves it.

The Samurai’s five-speed (natch) has the requisite gearing spread needed to put all of its 63 horsepower to good use. The Suzuki doesn’t weigh much, just a little over 2000 pounds, so it doesn’t need much. The fuel tank hides 10.6 gallons behind a skid plate, and after two days and 70 miles of rough going, often in four-low, the gauge showed just under half a tank consumed, though the 4Runner and Montero were down to a few gallons.

The Suzuki’s thrift partly makes up for the fact that it has the roughest ride of the three. Rolling over the knottiest stuff, your speeds are cut to a crawl lest the Samurai seizure itself to pieces. “I need a better bra for this,” grumped Woodward after a stint at the tiller, and she beelined back to her cushier Montero. Compared to the other two trucks, which are frolic-mobiles aimed at young outdoorsy types, the Montero is the adult in the room. Also formerly marketed here as the Dodge Raider, the severely upright and slightly uptight Montero is all business, a versatile, shockproof United Nations fleet car built more for ferrying aid workers into the malaria-infested far corners than whisking American moms to the mall.

Badged as the Pajero, the name it wears outside of the U.S., the Montero won the Paris-Dakar Rally 15 times, more than any other four-wheeled vehicle. They sold many more 4Runners here, and everyone thinks the Samurai is adorbs, but only one of these trucks comes with an international racing pedigree. It was also the one sold in the most variations, there being two-and four-door models, a 2.6-liter four-cylinder or a 3.0-liter V-6, and a choice of automatic or manual transmissions.

As with all Toyota trucks of the ’80s, the 4Runner feels almost like a sports car compared to today’s mastodons. You sit practically on the floor, legs and arms out, as if in a Celica on stilts. The shifter is so tall and light that two fingers move it without straining. The only truck in our group with power retractable rear glass also has a four-pot, the famous 22R, as suffused with a reputation for reliability as it is with torque. The long wheelbase offers plenty of squish and forgiveness—or at least it feels so compared to the bucking Suzuki. Lots of people have jacked up these things over the years with monster springs and tires. In the process, a pleasant desert roamer was lost.

Locked in low, our three little trucks ambled and bounced like radio-controlled Tamiya buggies playing in a huge sandbox, eventually scaling a steep and broken incline to our first campsite. Everything inside was tossed, and when the photographer opened the Montero’s large side-hinged door to retrieve a lens, one of our plastic water jugs came tumbling out and cracked open on the rock. Quick action stemmed the jug’s loss at 50 percent, but out in the remote canyons, in 33-year-old trucks bought on the cheap, the water supply was never far from mind.

Here at Murphy’s Hogback, the Murphy brothers, Jack, Tom, and Otho—who wrote a book in 1965 about the old pioneer days called The Moab Story—ran cattle around the time of World War I. A long foot trail leads to Murphy’s Point, where the family once occupied a dirt-floor log cabin with gobsmacking views to the west over the Maze district and its byzantine complex of interwoven slot canyons. One time, Maw Murphy was said to have thrown boiling water through a window into the face of the local chief to keep him from beating a woman. He came by the next day to tell her that she was “heap brave woman.”

The sun sank behind the distant Orange Cliffs while we fried up black beans and tortillas and told our own stories of vistas so dazzling that they can turn a pair of brown eyes blue, and of a few hairy moments where trucks teetered on two wheels. The stars switched on one by one until the whole sky was paved with diamond dust.

As the eyes must adjust to a tranquil darkness that is uncommon in our modern age, so, too, must the ears adapt to the blanketing silence of Utah’s canyon country. Here, you can gaze out across 25 miles of the earth’s surface and hear nothing but your own circulatory system. The muted peace and the slight night chill meant that sleep came fast and deep in our tents.

In the morning, we discovered the tracks—not of the bighorn sheep that roam the area, but of nocturnal furry souls that had inspected our vehicles inside out and from bumper to bumper in the night. Judging by the number of tiny paw prints in its layer of dust, the Suzuki’s engine had hosted a raging rodent convention. We packed up and carried on, eager to leave before the critters discovered that ’80s trucks have tasty wiring.

We reached the halfway point at White Crack, parked the trucks, and hiked out along an increasingly narrow spine of bleached rock to where it ended as giant geologic mushrooms towering over the lower basins of Island in the Sky. Somewhere unseen down in the deep gulches in front of us, the Green River collided with and donated its silty waters to the mighty Colorado. If you were a pinyon jay, you could fly from White Crack to an overlook viewpoint in two minutes to see the convergence yourself. As a human, you would need to drive 155 miles from this spot, including scaling Elephant Hill, one of the most tortuous four-wheeling trails in the national park system, then hike a mile to the overlook. Such is the tourist conundrum posed by this harsh and undeveloped terrain.

Having crossed over to the Colorado River side of the plateau, we trundled on at about 6 mph, going against the occasional traffic. Most people do the trail in a clockwise direction, from the Colorado River to the Green River side. Some heavily modified Wranglers painted in the same arclight colors as cans of energy drink came roaring up to us in a billow of dust from their 33-inchers. Kindly, they usually ground to a stop and let our convoy pass. We got one or two vigorous thumbs up, but most Jeepers, ensconced in their air-conditioned rock chariots and blasting their iTunes, just looked on in pity. This isn’t like your local cars and coffee; by and large, you don’t get points in the four-wheeling world for head-bobbing your way slowly along a trail in vintage stock equipment. Everyone wants to go faster.

We made it to our final campsite at the bottom of a thousand-foot wall into which a switchback road had been cut, known as the Shafer Trail. An old stock trail named for brothers Frank and John Shafer, who moved to Moab in 1878, the Shafer was remade in the uranium boom into a shelf road that leads travelers up off the White Rim and back toward Moab—and a shower. It is an acrophobe’s nightmare, the road at points about a Jeep-and-a-half wide, skirting what seems like a bottomless drop-off into a horseshoe-shaped chasm, which opens out to a gripping view of the frosted 12,000-foot peaks of the La Sal Range. It is, as Abbey said, the most beautiful place on earth.

We met up and camped with friends who were supposed to join us for the whole trip in an older Lexus GX470 set up for overlanding, but the rig had blown out an air shock on a trail near Arches National Park a couple days earlier and was stranded in Moab getting repairs. They seemed happy to be with us for one night at least, but in the darkness, the rodents became more daring, somehow penetrating the sealed-up Lexus and raiding its snack bin. We took it as a sign to retreat back to civilization, shaking the dust out as we went. Months later, Logan texted, “There’s still red streaks coming out of the seams every time I wash it. It will never be clean again.”

Toyota’s original fun-time SUV is, amazingly, still in production, still riding on the same platform as the contemporary compact pickup, and still a capable off-roader when optioned for dirt. But it’s no longer cheap, its base price starting above $36,000. Mitsubishi invested heavily in the Montero and reaped hearty sales with it through three generations, until the company lost interest in being cool and authentic and dumped the truck from its U.S. lineup in 2006.

Likewise, the Samurai yielded in 1995 to low sales and mounting lawsuits for its supposed tendency to roll over in accidents. Its replacement, the Suzuki Sidekick and Vitara, soldiered on until Suzuki quit the American car market altogether in 2012. However, the Samurai lives on elsewhere under its original name, the Jimny, and a redesigned version of this cheap and tough little off-roader debuted last year in overseas markets.

We hope Suzuki will find the gumption to return to the U.S. with it. In the meantime, we’ll be returning ourselves to this place, because no matter how many times you come to Utah’s canyon country, the itch is never fully scratched.

1987 Suzuki Samurai

Engine Inline-4, 1324 cc

Power 63 hp @ 6500 rpm

Torque 76 lb-ft @ 3500 rpm

Weight 2100 lb

Fuel tank 10.5 gal

Tires 205/70-15

Price when new $6950

Hagerty #2 value $10,000–$14,000

1987 Mitsubishi Montero

Engine Inline-4, 2555 cc

Power 106 hp @ 5000 rpm

Torque 142 lb-ft @ 2500 rpm

Weight 3260 lb

Fuel tank 15.9 gal

Tires 225/75-15

Price when new $10,409

Hagerty #2 value $11,500–$15,000

1987 Toyota 4Runner

Engine Inline-4, 2366 cc

Power 116 hp @ 4800 rpm

Torque 140 lb-ft @ 2800 rpm

Weight 3520 lb

Fuel tank 17.1 gal

Tires 225/75-15

Price when new $14,558

Hagerty #2 value $15,000–$20,500