Media | Articles

I took my 15-year-old nephew on an 850-mile rally in a 1949 Cadillac

Occasionally, you can achieve a narrow and fleeting kind of celebrity by appearing in a car magazine. As did my 15-year-old nephew Lucas when I wrote earlier this year about his plight. He’s a teenager with an obsession for old things and old cars at a time of life when most kids are preoccupied with social media and its demands for pop-cult conformity. Lucas’s passions have only sharpened as he’s aged, and at a cost; if you want a social life at 15, it might be best to keep to yourself the wonders of Cuphead, an eccentric video game with a jazzy 1930s cartoon theme and soundtrack, or old 16-millimeter newsreels unearthed in antique shops.

Emails flowed in, one even offering a cash donation to Lucas’s future car fund. A beguiling note came from Scott Dorsey at the Freedom Road Rally, inviting Lucas to join Dorsey’s next six-day, 850-mile vintage-car tour, which this year was aimed at the Adirondack hinterlands of New York. Dorsey has been organizing tours under his Freedom Road Rally brand since 2004, and though he makes efforts to encourage youth participation, teenagers are not his prime demographic. Nonetheless, after reading about Lucas, he figured the kid would enjoy a week in the company of like-minded antique-car lovers, especially after more than a year of closeted pandemic isolation. Really, Dorsey had no idea. Lucas was over the fence and around the moon with joy when we told him, and for the next three months, he periodically texted me updates of the number of seconds remaining until departure.

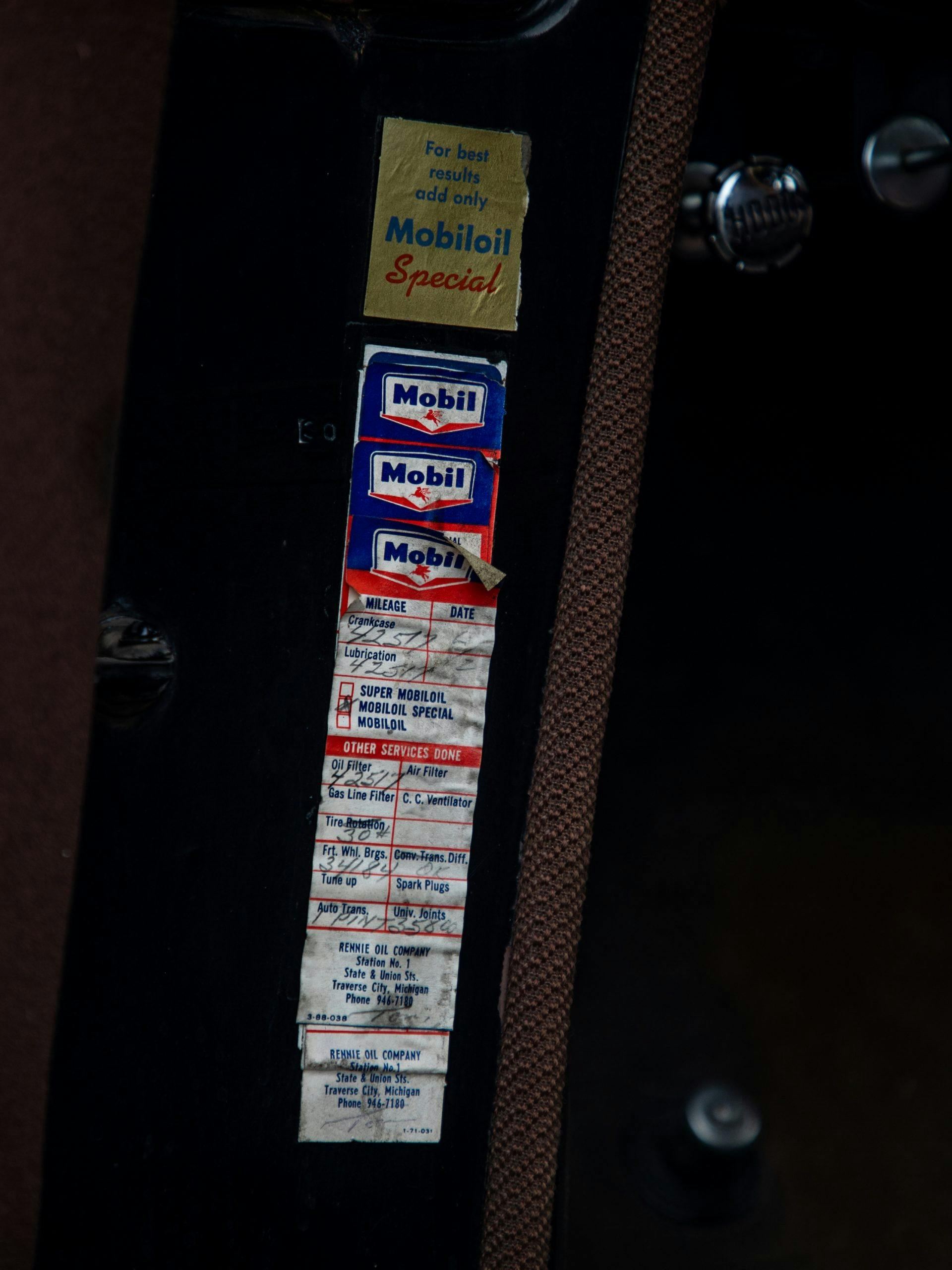

Unfortunately, Lucas is still too young to drive, so the duty fell to your humble narrator to obtain a suitable vintage car and act as chauffeur. Lately, Lucas had been texting me a string of ads for late-1940s and early ’50s cars, so I requested the 1949 Cadillac Series 62 sedan out of the Hagerty garage. It was an unknown quantity, an unrestored original showing 47,000 miles on an odometer that probably hasn’t spun much in the past couple of decades. Thankfully, I didn’t learn until after the rally that the car previously belonged to old friends of the Hagerty family. “Anything can happen or nothing can happen,” summed up our fleet manager, Tony Pietrangelo, and with that, the Cadillac was booked in.

We rolled out from Lucas’s house precisely at 7:00 a.m., just as the sun was starting to cook up yet another muggy late-July day in Detroit. Due to a shipping snafu, the Cadillac had only been trucked as far as Canton, Michigan, on its journey to the rally start in Syracuse, so the job landed on Lucas and me to jockey it the extra 500 miles out (and back), more than doubling our anticipated mileage. If the old Cad was intending to blow, it would have ample opportunity.

By the time we were passing The Glass House, Ford’s aquamarine headquarters near Detroit, Lucas had the tunes up and running, streaming from his phone to a Bluetooth speaker he borrowed from his mom. It started with Kitty Kallen songbirding “It’s Been a Long, Long Time” in 1945 with the Harry James Orchestra, then Bobby Darin belting out “Mack the Knife,” then Sinatra doing it “My Way,” and so on through a collection of brassy American standards. Lucas sang right along, knowing all the words, as we whisked through Motown’s concrete canyons, the wind wings cranked out on the old Cadillac, and, as Kerouac wrote of his own journey in a ’47 Cad, “nowhere to go but everywhere.”

Marketplace

Buy and sell classics with confidence

Out on the Ohio Turnpike, Cadillac’s first overhead-valve engine, a 331 V-8 still wearing its original chipped and stained navy-blue paint, inhaled the miles without a wobble. But the four-speed Hydra-Matic was prone to snap our heads with a hard shift, and it was leaving unseemly puddles of ATF at every fuel stop. In a ’49 Cadillac, you pull up the carpet in the passenger footwell to check the transmission dipstick, and it showed full. Actually, more than full (a fact that would become revelatory later), and we figured that as long as the transmission could lube itself, it probably wouldn’t strand us. Probably.

After nine hours of superslab covered at the Cadillac’s most comfortable speed of 63-ish mph, Syracuse finally rose on the horizon. The meet-up hotel was in the process of converting from a Holiday Inn to a Ramada, and it was suffering from glaring lack of upkeep—including a broken water boiler, meaning cold showers for all. While I was in the lot checking over the Cadillac and the other cars in the rally, Lucas texted from the room that there were stains on the walls and some kind of unidentifiable ick on the TV remote. When faced with such situations, with trifling imperfections in the otherwise antiseptic polyester norm of modern highway travel, I always relativize. “Well, it sounds better than a foxhole on Iwo Jima,” I said. Lucas proved immune to this teachable moment about maintaining a broad perspective and instead texted his mother, who then texted me with an offer to pay for a room at another hotel.

“So that’s how it’s going to be,” I ranted to myself with a flash of irritation. When the going gets tough, the kid gets on iMessage with Mom. Then followed the same huffy observation that every adult has made at one time or another since Adam and Eve: “Things sure have changed since I was a kid!”

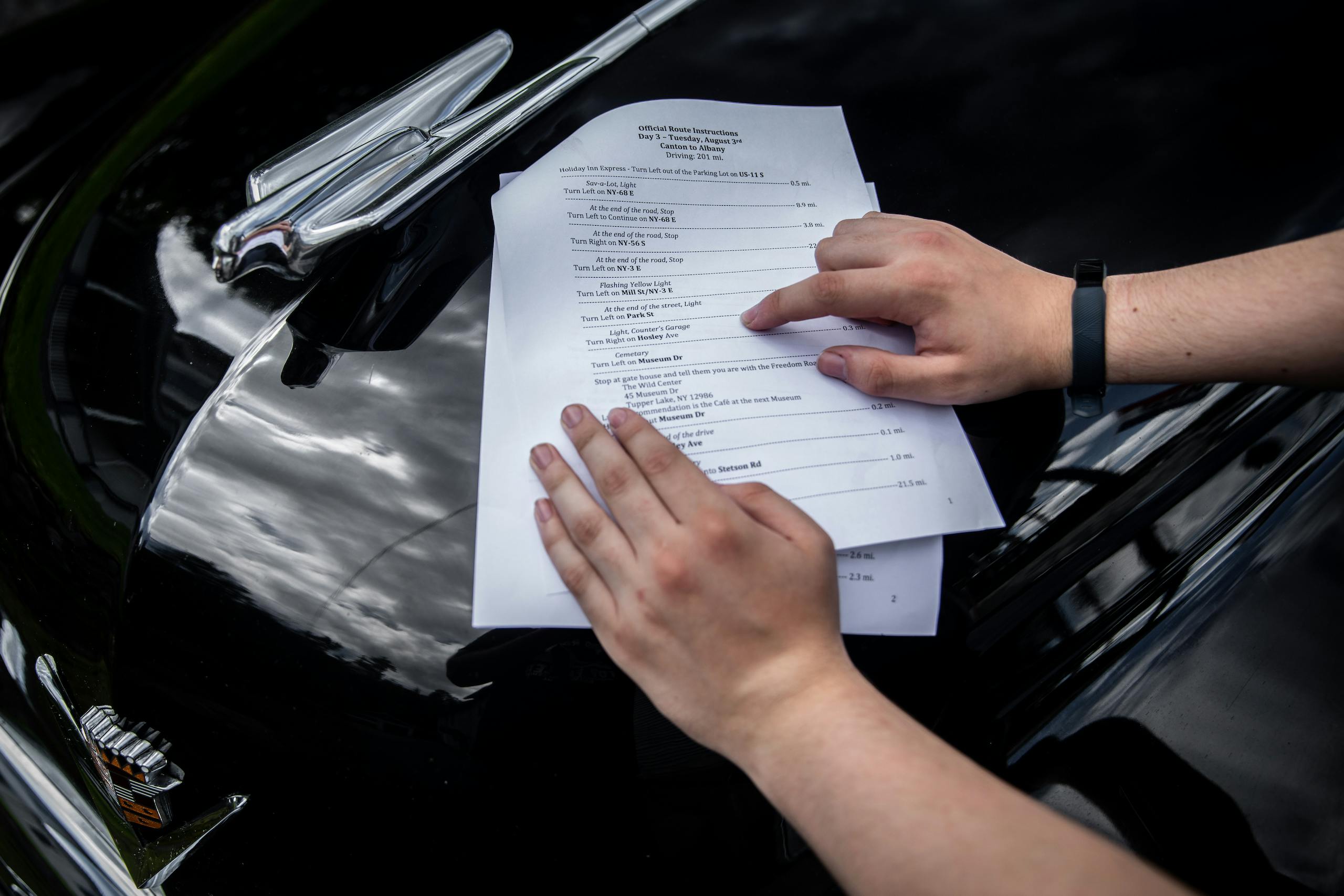

Dorsey’s concept of a road rally can be summed up as follows: Pick a scenic corner of rural America, give everyone exceedingly clear directions, limit the daily slog to between 100 and 200 miles, and sprinkle in lots of stops at the type of little museums and offbeat roadside attractions that rushing travelers never seem to make time for anymore. While the name of the event, the Freedom Road Rally, seems pregnant with political overtone in this overheated age, Dorsey actually came up with it not long after terrorists in 2001 forever ruined his birthday of September 11. And about four years ago, he declared his rally a “politics-free zone, because we’re all on vacation and there’s no point in arguing about sh*t we can’t do anything about.”

On the first day, our band of old-car rallyists cruised a two-lane back road to our first stop, the historic Fort Ontario, a star-shaped citadel on Lake Ontario that dates back to before the Revolutionary War. It was captured, destroyed, and rebuilt several times, most recently after the Civil War, when gun ports for 32-pound howitzers were installed into a V-shaped cauldron of walls that lead to the main entrance. During an attack, the guns were there to fire canisters full of iron tennis balls at the oncoming enemy, the walls constructed of jagged stone in order to scatter shell fragments for maximum carnage. Fortunately, it was never needed.

After that, we motored on to the Antique Boat Museum in Clayton, New York, a tribute to the golden age of stained and shellacked watercraft from a bygone era in the Thousand Islands region of the St. Lawrence River. Among its pristine Chris-Craft cruisers and Gar Wood runabouts is La Duchesse, a 106-foot houseboat built in 1903 as a summer getaway for hotelier George Boldt of the famed Waldorf-Astoria in New York. After years of neglect that culminated in its sinking, the craft has been refloated on a new hull and restored to some of its original, if somewhat musty, grandeur.

The relaxed cadence of the Freedom Road Rally began to emerge. Cars drifted in small groups and with no particular hurry from destination to destination. The $2400 entry fee included all hotel accommodations and venue tickets, but dining was on your own, leaving participants to pick their own poison, whether it be a hurried McDonald’s or a waterside bistro patio with a view of the 1000-foot bulk freighters plying the St. Lawrence. “It’s like leaving the 21st century,” said JoAnn Martinec from Corning, New York, who was navigating for husband George in their turquoise 1957 Chevy Bel Air. “You breathe slower, you breathe easier, there’s no fast pace, and you discover so much about the country over these road rallies.”

People stayed as long or as little as they desired, then moved on. We toured Boldt’s island palace known as Boldt Castle, which the hotel magnate built for his wife Louise and then in despair abandoned upon her premature death. Lucas was enamored by the graffiti on the unfinished upper floors that went back decades, including a visitor from Bay Shore on Long Island who wrote on the wall in 1928. We visited a museum devoted to the western-themed sculptures and paintings of Frederic Remington, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. At a nature park called the Adirondack Experience, we saw otters frolic in a man-made waterfall and hiked an elevated walkway through the forest canopy.

Fans of the original 1960s Star Trek series were bedazzled by a meticulous re-creation of the show’s sets constructed in a warehouse in the unlikely locale of Ticonderoga, New York. Tour guide Drew Malone, a dead ringer for next-gen Star Trek cast member Wil Wheaton, explained how the Federation of Planets flag in Captain Kirk’s conference room was just a lightly disguised Cuban flag, a tribute to Desilu Productions co-founder Desi Arnaz. And how the original Trek was one of the first television shows aired entirely in color, causing set designers to comb hotel and restaurant catalogs of the 1960s for their wildest fabrics. Those are now unobtainable and thus the Enterprise’s original psychedelic bedspreads were remade at great expense by the museum. “This is basically a 13,000-square-foot man cave,” boasted Malone.

In between stops, Lucas would rattle off conversation topics rapid-fire, his head a vast storehouse of factoids about the world’s tallest buildings, the events of 9/11, the history of the Walt Disney Co., the history of the Tucker automobile, and so on. I made him write down each new topic in a notebook kept on the floor of the Cadillac, partly just to slow him down. Entries included:

“Terminal velocity, falling from Empire State.”

“Hawaii plates.”

“T. Dewey Highway.”

“Huntsman spiders.”

“Model T that drove around the world.”

“RHD vs LHD. Why??”

He also called out all the antique stores he spotted (or, those he didn’t miss because he was staring at his phone—sorry, Lucas), and our finned Cadillac dutifully screeched to a halt. The shops ranged in ambience from Main Street resale storefronts full of worthless detritus to ancient old houses with tilting floors and dusty artifacts from America’s past. A practiced shopper of such castoffs, Lucas knew what he was after: any 1980s electronics, and 16-millimeter films to run through his 1943 Bell & Howell projector, which we had lugged along on the trip despite it weighing about as much as a Muncie Toploader.

In one shop, he found one, packed in a canister with no markings. After examining only enough frames to determine that the reel was black-and-white and probably very old, he bought it for 20 bucks and a promise to email the shopkeeper with details of its contents. That night at the hotel, he told our fellow rallyists, gathered around the lobby to watch some of the films that we had lugged out from Detroit—including a Donald Duck short and a news documentary about the 1968 presidential primary—that the new reel would be unveiled the following night. Anticipation buzzed through the rallyists, for by now, Lucas’s evening screenings were legendary.

We were getting to know our fellow rallyists. Bob Oliver and Bill Stryker were two old friends from Jersey crewing a 1964 Chrysler Newport convertible with a leaky power-steering pump. A retired IRS accountant and Vietnam vet, Stryker also drove buses as a side hustle for 42 years and maintains an active interest in them. “I’ll vouch for that,” said Oliver, who worked for the power company, “because we go to every bus show in the country.”

Scott and Shelly Thams of Clarkston, Michigan, were driving a pristine red 1967 Chevrolet Camaro SS, a long-term restoration project. Thams has done the Great Race twice in a 1914 Model T Speedster capable of 60 mph. The difference with the Freedom Rally: “We get to see things; in the Great Race, you never get to see anything.”

Eugene Toner and Ben Renninger were two young mechanics paid by Dorsey to crew the rally’s sag wagon, a Ford F-150 full of tools and towing a flatbed tandem- axle trailer. By day five, the trailer had yet to see use, the worst problems thus far being the Newport and its trail of iridescent power-steering fluid and a 1940 Ford with a small-block Chevy bucking from fouled injectors. The Ford’s performance improved greatly after Toner suggested that its owner try administering a full-throttle Italian tuneup. Toner told me later that loading one or two cars a day on the trailer was normal for a Freedom Rally.

We were happy to stay off of it. At some point, the leak in the Cadillac’s transmission slowed to just the occasional drip, and it simultaneously started shifting more smoothly. We realized that the Hydra-Matic, which holds a voluminous 11 quarts of fluid, had simply been overfilled at some point and was shedding its unwanted excess. It gave us no more trouble for the rest of the trip.

At moments during the long hours, I wondered if Lucas was having any fun. I was doing all the driving, so there wasn’t much for him to do except stare out the window or look at his phone. Some of the stops, including the Baseball Hall of Fame and the Star Trek museum—a sport he has barely played and a TV show he had never seen—were only marginally interesting to him. The buildup to this trip had been so momentous, his parents and grandparents all telling him it was the opportunity of a lifetime and that he would see and learn and change so much. Was I failing him as an uncle? Was this supposed to be like one of those road movies where a musical montage plays while a slow but lasting bonding happens and life destinies are changed?

Eventually, there was a moment of clarity: Lucas has been on this earth for 15 years and I, the uncle who lives 2400 miles away in Los Angeles, was getting him for six days. The main objective was to have a good time on a summer romp, not to make this trip a series of teachable moments. And I realized in my own teachable moment that my parenting skills are dubious (I thought nothing of taking a 15-year-old kid on a 2000-mile drive in a car with no seatbelts, a steel dashboard, drum brakes, and 6-volt headlights) and that it wasn’t my job or Scott Dorsey’s job or the Adirondacks’s job to teach Lucas anything. He would see what he would see and learn what he wanted to learn, and if it was nothing beyond that it takes three pumps to start a stone-cold ’49 Cadillac, then so be it.

On our last night, Lucas loaded up the mystery reel. It opened with none other than Charles Lindbergh explaining the freshly invented wonders of transcontinental air travel, and it followed a group of passengers as they hopscotched across America in a gurgling Ford Trimotor. Coast to Coast in 48 Hours was the breathless title of this 10-minute film, probably shot around 1930, when taking two days to get from New York to Los Angeles was science-fiction stuff. The rallyists watched, transfixed. Then, right after the last bit of film went clacking through the projector, its bulb burned out. Movie night was over, as was our journey.

We parted company from the 2021 Freedom Road Rally after touring the incomparable Northeast Classic Car Museum in Norwich, New York, which constantly churns its borrowed collection of pristine classics to keep things interesting. We also visited the considerably quirkier Wheels in Time Museum in a house across the street. Proprietor Eric Andrade describes his personal collection of 5000 miniature vehicles as “telling the story of American history through die-cast.”

Then we hit the road for home, doing one last slow cruise up Woodward Avenue past the former General Motors Building, the words of that old Johnny Cash song playing in my head: “I left Kentucky back in ’49 and went to Dee-troit working on an assembly line, and the first year they had me putting wheels on Cadillacs…” However, before we pulled into the driveway, we completed one last mission: Lucas slid into the driver’s seat. We did several slow laps around a large hotel lot, Lucas getting the feel of the steering and brakes. He would make a turn, then forget that you have to unwind the wheel if you wish the car to go straight again, and we nearly ran over a hotel staffer sitting on a curb having a smoke break. But she was a good sport about it, and I realized Lucas had never driven a car before. “Nope, this is my first one,” he confirmed. A 1949 Cadillac—it seemed fitting.

1949 Cadillac Series 62 Sedan

Engine: 331-cid V-8

Power: 160 hp @ 3800 rpm

Torque: 292 lb-ft @ 2200 rpm

Weight: 4000 lb

Cruising Speed: 63 mph

Price when new: $3050

Hagerty #2-condition value: $26,500–$38,000

Lucas’s trip, in his own words

The day had come at last. I was so excited, I got up an hour ahead of my alarm and thought about the interesting and amazing things we’d be doing and seeing. The past year and a half had been depressing and restrictive, and I was finally going to be able to go out and experience something besides my house.

On the way to New York, we got quite a few thumbs-up and waves from people passing by. Each time, it reinforced the elegance and beauty of the Cadillac we had chosen, which carried us along without a single issue. Whenever we stopped for gas, people would come over and compliment the car, at which point I would take the opportunity to show them how the gas cap was hidden under the taillight. What a feature, by the way. I don’t think you would see that level of creativity in cars today.

When we pulled into the hotel on the first day, we were met with a parking lot full of different cars, from 100 percent stock cars to ones with overhauled engines and modern interiors. There was a 1950s Thunderbird, which I adore, and a Volkswagen Thing with a nautical theme, including a life preserver and an outboard motor, which was just fun. Going down the road, we saw a red 1951 Oldsmobile for sale. I adore those Oldsmobiles. Something about the little tab under the headlights really ties the whole thing together. We pulled over and I made sure to write down the number—though after chatting with the guy a bit, I had to admit to myself that I didn’t have the money to buy it.

All the while, the Cadillac kept on moving, and (according to Aaron) it handled beautifully. Along the way, we stopped at a few antique stores. One store was full of war memorabilia, and another had a box of butchered car radios and headlights. By the end, I had picked up such gems as an old eight-track cassette, the film titled Coast to Coast in 48 Hours, and a Life magazine from July 4, 1969, titled “Special Issue: Off to the Moon.” When I showed it to another rally participant, he said he didn’t believe Americans went to the moon, and we had quite a discussion.

On the last day of the trip, at the Northeast Classic Car Museum, there was a 1947 Hudson with an interesting-looking grille, a 1959 Edsel (I prefer the ’58; the ’59 is too tame!), a rare Cadillac with a V-16 engine, some motorcycles that looked more like rockets with seats and handlebars, and a Packard with a hood ornament that was so sharp I bet you could cut carrots on it.

But my favorite thing there was a 1956 DeSoto Firedome convertible. I love the 1956 Chryslers. In my book, 1956 was the last year of a prewar era of styles, and Chrysler hit it home that year. Not to mention, this one had the optional built-in record player! It was a sight to see and a perfect ribbon on that whole museum.

I thought I would miss the modern amenities of AC and reclining seats, but wind wings and vents kept the car cool, and the Cadillac’s couch-like seats were plenty comfortable. On our way back through Detroit on the last leg of our journey, the cozy interior and elegant exterior of the Cadillac solidified my love for these classics. I will have one, someday.